When you hear about an ozone hole, it’s

typically the one that forms over Antarctica each year in southern

spring (northern autumn). But since about mid-March 2020, scientists

using satellite data have been tracking a “mini” Arctic ozone hole. It’s

small compared to Antarctica’s annual hole, but unusually large for the

Arctic. Conditions in the air above the Arctic – including powerful

westerly winds that trapped cold air in a polar vortex – caused this rare strong reduction of Arctic ozone. Atmospheric scientist Martin Dameris at the German Aerospace Center in Oberpfaffenhofen, who is tracking 2020’s Arctic ozone hole, was quoted in Nature as saying:

From my point of view, this is the first time you can speak about a real ozone hole in the Arctic.

Those freezing temps in the stratosphere

over the Arctic, by the way, follow abnormally warm temperatures in the

stratosphere over Antarctica last September and October. NOAA scientists said then that the abnormal warmth in the stratosphere dramatically limited ozone loss, resulting in the smallest Antarctic ozone hole observed since 1982.

Abnormally warm over Antarctica half a year

ago. Abnormally cold over the Arctic in recent weeks. Is that a

coincidence? Climate is complex, and Earth’s climate is changing, so

it’s hard to know.

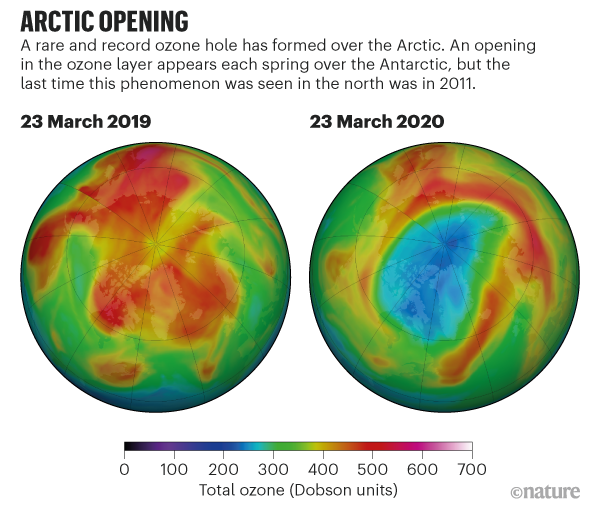

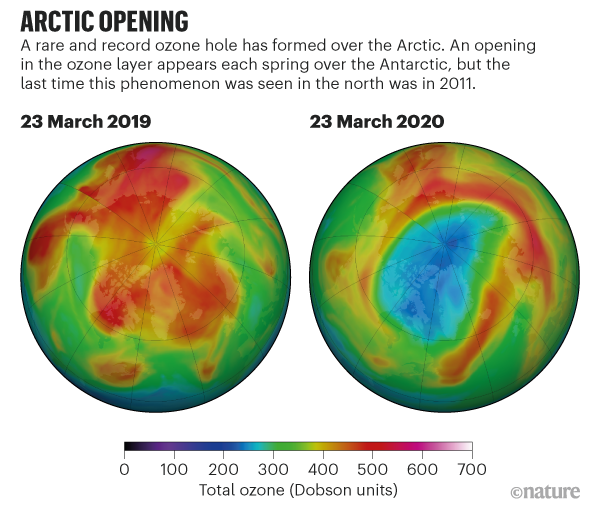

A comparison of ozone levels over the Arctic in March 2019, and in March 2020. Image via Nature.

Here’s

what scientists do know. They know that small ozone holes have been

spotted over the Arctic in previous years, but that 2020’s Arctic ozone

depletion is much greater. Diego Loyola of the German Aerospace Center said in a statement from ESA:

The ozone hole we observe over the Arctic this year has a maximum extension of less than 1 million square kilometers (400,000 square miles). This is small compared to the Antarctic hole, which can reach a size of around 20 to 25 million square kilometers (8 to 10 million square miles) with a normal duration of around 3 to 4 months.

Overall, the Arctic’s ozone depletion tends

to be significantly less than that over Antarctica. Holes in Earth’s

ozone layer above either pole are driven by extreme cold – stratospheric

temperatures below -80°C (-112°F) – sunlight, powerful winds and

substances such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). As reported in Nature, in 2020, powerful westerly winds flowed around the North Pole. They trapped cold air within a polar vortex. The report in Nature said:

There was more cold air above the Arctic than in any winter recorded since 1979.

ESA said:

By the end of the polar winter, the first sunlight over the North Pole initiated this unusually strong ozone depletion – causing the hole to form. However, its size is still small compared to what can usually be observed in the southern hemisphere.

Diego Loyola said:

Since March 14, the ozone columns over the Arctic have decreased to what is normally considered ‘ozone hole levels,’ which are less than 220 Dobson units. We expect the hole to close again during mid-April 2020.

ESA also explained:

The ozone layer is a natural, protective layer of gas in the stratosphere that shields life from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation – which is associated with skin cancer and cataracts, as well as other environmental issues.

In the 2018 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion, data shows that the ozone layer in parts of the stratosphere has recovered at a rate of 1-3% per decade since 2000. At these projected rates, the Northern Hemisphere and mid-latitude ozone is predicted to recover by around 2030, followed by the Southern Hemisphere around 2050, and polar regions by 2060.

This

timelapse image shows the launch of a weather balloon at Earth’s South

Pole in the southern spring (northern autumn) of 2019. Balloons like

this one can carry ozone-measuring sondes

that directly sample ozone levels vertically through the atmosphere. In

the Arctic, weather balloons like this one are launched from observing

stations in various places, including the Polarstern icebreaker,

which is frozen in sea ice for a year-long expedition. Other scientists

monitor Earth’s ozone hole from space via satellites. Image via NOAA.

Bottom line: The “ozone hole” commonly

referenced is the hole over Antarctica that forms each southern spring

(northern autumn). But beginning around mid-March 2020, satellite data

revealed that ozone concentrations over the northern polar regions have

plummeted, causing a “mini-hole” in the ozone layer over the Arctic.

When you hear about an ozone hole, it’s

typically the one that forms over Antarctica each year in southern

spring (northern autumn). But since about mid-March 2020, scientists

using satellite data have been tracking a “mini” Arctic ozone hole. It’s

small compared to Antarctica’s annual hole, but unusually large for the

Arctic. Conditions in the air above the Arctic – including powerful

westerly winds that trapped cold air in a polar vortex – caused this rare strong reduction of Arctic ozone. Atmospheric scientist Martin Dameris at the German Aerospace Center in Oberpfaffenhofen, who is tracking 2020’s Arctic ozone hole, was quoted in Nature as saying:

From my point of view, this is the first time you can speak about a real ozone hole in the Arctic.

Those freezing temps in the stratosphere

over the Arctic, by the way, follow abnormally warm temperatures in the

stratosphere over Antarctica last September and October. NOAA scientists said then that the abnormal warmth in the stratosphere dramatically limited ozone loss, resulting in the smallest Antarctic ozone hole observed since 1982.

Abnormally warm over Antarctica half a year

ago. Abnormally cold over the Arctic in recent weeks. Is that a

coincidence? Climate is complex, and Earth’s climate is changing, so

it’s hard to know.

A comparison of ozone levels over the Arctic in March 2019, and in March 2020. Image via Nature.

Here’s

what scientists do know. They know that small ozone holes have been

spotted over the Arctic in previous years, but that 2020’s Arctic ozone

depletion is much greater. Diego Loyola of the German Aerospace Center said in a statement from ESA:

The ozone hole we observe over the Arctic this year has a maximum extension of less than 1 million square kilometers (400,000 square miles). This is small compared to the Antarctic hole, which can reach a size of around 20 to 25 million square kilometers (8 to 10 million square miles) with a normal duration of around 3 to 4 months.

Overall, the Arctic’s ozone depletion tends

to be significantly less than that over Antarctica. Holes in Earth’s

ozone layer above either pole are driven by extreme cold – stratospheric

temperatures below -80°C (-112°F) – sunlight, powerful winds and

substances such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). As reported in Nature, in 2020, powerful westerly winds flowed around the North Pole. They trapped cold air within a polar vortex. The report in Nature said:

There was more cold air above the Arctic than in any winter recorded since 1979.

ESA said:

By the end of the polar winter, the first sunlight over the North Pole initiated this unusually strong ozone depletion – causing the hole to form. However, its size is still small compared to what can usually be observed in the southern hemisphere.

Diego Loyola said:

Since March 14, the ozone columns over the Arctic have decreased to what is normally considered ‘ozone hole levels,’ which are less than 220 Dobson units. We expect the hole to close again during mid-April 2020.

ESA also explained:

The ozone layer is a natural, protective layer of gas in the stratosphere that shields life from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation – which is associated with skin cancer and cataracts, as well as other environmental issues.

In the 2018 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion, data shows that the ozone layer in parts of the stratosphere has recovered at a rate of 1-3% per decade since 2000. At these projected rates, the Northern Hemisphere and mid-latitude ozone is predicted to recover by around 2030, followed by the Southern Hemisphere around 2050, and polar regions by 2060.

This

timelapse image shows the launch of a weather balloon at Earth’s South

Pole in the southern spring (northern autumn) of 2019. Balloons like

this one can carry ozone-measuring sondes

that directly sample ozone levels vertically through the atmosphere. In

the Arctic, weather balloons like this one are launched from observing

stations in various places, including the Polarstern icebreaker,

which is frozen in sea ice for a year-long expedition. Other scientists

monitor Earth’s ozone hole from space via satellites. Image via NOAA.

Bottom line: The “ozone hole” commonly

referenced is the hole over Antarctica that forms each southern spring

(northern autumn). But beginning around mid-March 2020, satellite data

revealed that ozone concentrations over the northern polar regions have

plummeted, causing a “mini-hole” in the ozone layer over the Arctic.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire