The early evenings of February 27 and 28, 2020 feature a close pairing of the waxing crescent moon with the brightest planet, Venus. Look for them in the western twilight, shortly after sunset. The moon and Venus rank as the 2nd-brightest and 3rd-brightest celestial objects to light up the sky, after the sun. The moon and Venus don’t shine by their own light but by reflecting sunlight; they’re like beauties on a beach, basking in sunshine.

For the fun of it, we show you the planet Uranus relative to the moon and Venus on these evenings. But don’t expect to see Uranus without an optical aid. Uranus – 7th planet from the sun – is no brighter than the faintest visible star. It’s barely perceptible as a tiny speck of light on an inky, dark night. If you want to locate Uranus (tough to do in a twilight sky, and in the moon’s glare), you’ll need with a detailed sky chart like this one via SkyandTelescope.com. Read more from S&T: Ice Giants Neptune and Uranus

Venus is still appearing higher each evening in the west after sunset. Meanwhile, Uranus is sinking into the sunset glare. The two will pass on the sky’s dome, meeting up for a conjunction on March 9, 2020.

But back to our brilliant twosome, the moon and Venus…

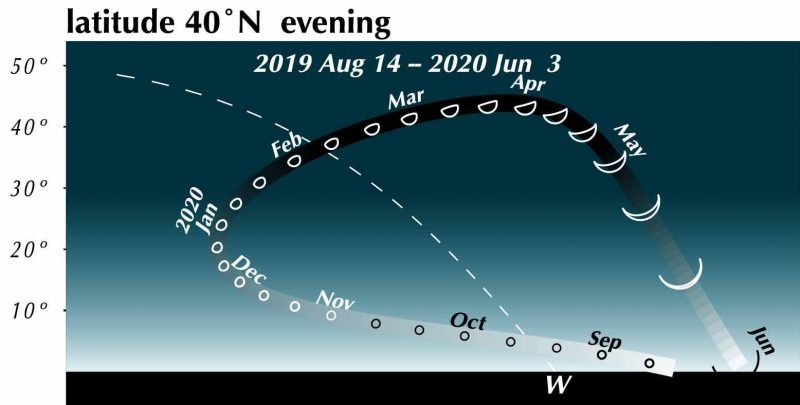

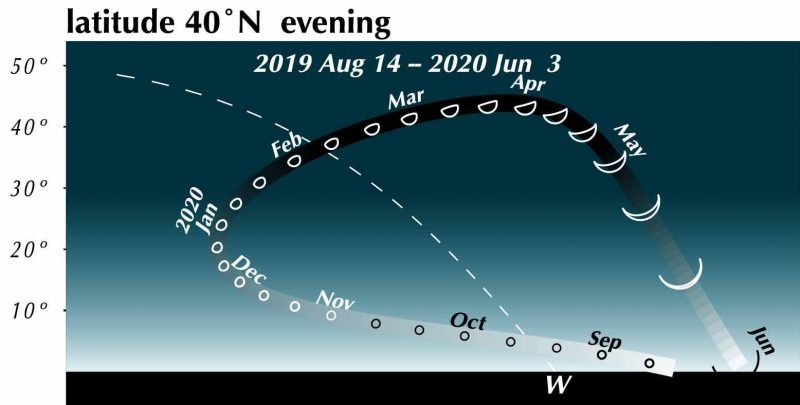

View larger. | Venus officially entered the evening sky on August 14, 2019, and will officially leave it on June 3, 2020, the day upon which it’ll pass between us and the sun. Venus shines at its brightest as the evening “star” in late April and early May 2020, when its disk is about one-quarter illuminated. By late May and early June 2020, people with good vision might be able to see the crescent Venus with the eye alone. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

Did you know Venus shows phases, much as the moon does? You need a telescope to see the phases of Venus. Because the moon and Venus appear close around February 27 and 28, 2020, you might think Venus’ phase (as seen through the telescope) should nearly match that of the moon. But, no, it’s not even close. The moon displays a waxing crescent phase on these dates, while Venus exhibits a waning gibbous phase.

Venus first entered the evening sky at full phase on August 14, 2019. Then it was far across the solar system from us, and we were seeing nearly all of its dayside. Right now, Venus still resides on the far side of the sun as seen from Earth, but it’s catching up to Earth in its smaller, faster orbit. We’re seeing less of its dayside: hence, a gibbous Venus.

Venus will move to the near side of the sun (Earth side) around late March 2020. At that juncture, Venus will have passed its half-illuminated last quarter phase, and start to show itself as a waning crescent. Venus will shine most brightly as the evening “star” in late April/early May 2020. Paradoxically, it’ll be a crescent Venus shining so brightly; the brightness will stem from the planet’s nearness to Earth, as, by that time, Venus will be hot on Earth’s heels in orbit.

Later on – late May/early June 2020 – people with good vision might even be able to see the crescent Venus with the eye alone. Venus will pass between us and the sun, leaving our evening sky, on June 3, 2020. Then the planet will be at the new phase, with its sunlit side turned entirely away from us. It’ll be a waxing crescent Venus that reappears in the east before dawn a few days later.

See an animation showing Venus phases in late 2019 and early 2020

This isn’t the moon. It’s the planet Venus as seen through the telescope. As Venus wanes in the evening sky it gets closer to Earth. The lit portion of Venus covers the greatest area of sky when its disk is about one-quarter illuminated. Image via Statis Kalyvas/ European Southern Observatory/ Wikimedia Commons.

Nowadays, we take the changing phases of Venus (and Mercury) for granted. Amateur astronomers with small telescopes watch them regularly. But in medieval times, when Earth was said to occupy a hallowed place in the center of the universe, the changing phases of Venus and Mercury were a revolutionary idea.

Both Venus and Mercury are inferior planets: they revolve around the sun inside Earth’s orbit. When Galileo (1564-1642) observed the phases of Venus and Mercury through his early telescope, he found the evidence he needed to prove that these worlds orbit the sun instead of Earth.

But the old idea of a Earth-centered cosmos died hard, as the Church and some astronomers were not quick to embrace the sun-centered model that had been advanced by Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) in the early 1500s. The cosmological model of Ptolemy – a Greek mathematician and astronomer who’d lived from the year 100 AD to the year 170 AD – held sway. See the contrast between Ptolemy’s model of the universe and the sun-centered model of Copernicus below.

Contrasting Ptolemy’s Earth-centered model with Copernicus’ sun-centered model. In the Earth-centered model, Mercury and Venus orbit the sun inside of the sun’s orbit around Earth. In the sun-centered model, Mercury and Venus orbit the sun inside of Earth’s orbit. Graphic via Amazing Space.

The Church ultimately accepted the model developed by Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), which placed the orbits of all the planets (except Earth) around the sun – yet the orbits of the sun (and moon) around a stationary Earth.

It wasn’t until 1838 that Frederic Bessel (1784-1846) finally proved conclusively that the Earth orbits the sun when he successfully found the parallax of the star 61 Cygni in 1838.

Thus the phases of Venus provided visual evidence of Venus’ motion around the sun in Galileo’s time. Those changing phases – which amateur astronomers with small telescopes will be watching in the coming months – provided a first step in the long and arduous journey in humanity’s acceptance of a sun-centered solar system.

The model developed by Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) places Earth at the center of the cosmos, with all the planets (except Earth) revolving around the sun, yet the sun and moon revolving around a stationary Earth.

Bottom line: On February 27 and 28, 2020, look west after sunset for the waxing crescent moon and brilliant planet Venus. The planet Uranus will be lurking – mostly unseeen – nearby.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Ti2ZFD

The early evenings of February 27 and 28, 2020 feature a close pairing of the waxing crescent moon with the brightest planet, Venus. Look for them in the western twilight, shortly after sunset. The moon and Venus rank as the 2nd-brightest and 3rd-brightest celestial objects to light up the sky, after the sun. The moon and Venus don’t shine by their own light but by reflecting sunlight; they’re like beauties on a beach, basking in sunshine.

For the fun of it, we show you the planet Uranus relative to the moon and Venus on these evenings. But don’t expect to see Uranus without an optical aid. Uranus – 7th planet from the sun – is no brighter than the faintest visible star. It’s barely perceptible as a tiny speck of light on an inky, dark night. If you want to locate Uranus (tough to do in a twilight sky, and in the moon’s glare), you’ll need with a detailed sky chart like this one via SkyandTelescope.com. Read more from S&T: Ice Giants Neptune and Uranus

Venus is still appearing higher each evening in the west after sunset. Meanwhile, Uranus is sinking into the sunset glare. The two will pass on the sky’s dome, meeting up for a conjunction on March 9, 2020.

But back to our brilliant twosome, the moon and Venus…

View larger. | Venus officially entered the evening sky on August 14, 2019, and will officially leave it on June 3, 2020, the day upon which it’ll pass between us and the sun. Venus shines at its brightest as the evening “star” in late April and early May 2020, when its disk is about one-quarter illuminated. By late May and early June 2020, people with good vision might be able to see the crescent Venus with the eye alone. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

Did you know Venus shows phases, much as the moon does? You need a telescope to see the phases of Venus. Because the moon and Venus appear close around February 27 and 28, 2020, you might think Venus’ phase (as seen through the telescope) should nearly match that of the moon. But, no, it’s not even close. The moon displays a waxing crescent phase on these dates, while Venus exhibits a waning gibbous phase.

Venus first entered the evening sky at full phase on August 14, 2019. Then it was far across the solar system from us, and we were seeing nearly all of its dayside. Right now, Venus still resides on the far side of the sun as seen from Earth, but it’s catching up to Earth in its smaller, faster orbit. We’re seeing less of its dayside: hence, a gibbous Venus.

Venus will move to the near side of the sun (Earth side) around late March 2020. At that juncture, Venus will have passed its half-illuminated last quarter phase, and start to show itself as a waning crescent. Venus will shine most brightly as the evening “star” in late April/early May 2020. Paradoxically, it’ll be a crescent Venus shining so brightly; the brightness will stem from the planet’s nearness to Earth, as, by that time, Venus will be hot on Earth’s heels in orbit.

Later on – late May/early June 2020 – people with good vision might even be able to see the crescent Venus with the eye alone. Venus will pass between us and the sun, leaving our evening sky, on June 3, 2020. Then the planet will be at the new phase, with its sunlit side turned entirely away from us. It’ll be a waxing crescent Venus that reappears in the east before dawn a few days later.

See an animation showing Venus phases in late 2019 and early 2020

This isn’t the moon. It’s the planet Venus as seen through the telescope. As Venus wanes in the evening sky it gets closer to Earth. The lit portion of Venus covers the greatest area of sky when its disk is about one-quarter illuminated. Image via Statis Kalyvas/ European Southern Observatory/ Wikimedia Commons.

Nowadays, we take the changing phases of Venus (and Mercury) for granted. Amateur astronomers with small telescopes watch them regularly. But in medieval times, when Earth was said to occupy a hallowed place in the center of the universe, the changing phases of Venus and Mercury were a revolutionary idea.

Both Venus and Mercury are inferior planets: they revolve around the sun inside Earth’s orbit. When Galileo (1564-1642) observed the phases of Venus and Mercury through his early telescope, he found the evidence he needed to prove that these worlds orbit the sun instead of Earth.

But the old idea of a Earth-centered cosmos died hard, as the Church and some astronomers were not quick to embrace the sun-centered model that had been advanced by Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) in the early 1500s. The cosmological model of Ptolemy – a Greek mathematician and astronomer who’d lived from the year 100 AD to the year 170 AD – held sway. See the contrast between Ptolemy’s model of the universe and the sun-centered model of Copernicus below.

Contrasting Ptolemy’s Earth-centered model with Copernicus’ sun-centered model. In the Earth-centered model, Mercury and Venus orbit the sun inside of the sun’s orbit around Earth. In the sun-centered model, Mercury and Venus orbit the sun inside of Earth’s orbit. Graphic via Amazing Space.

The Church ultimately accepted the model developed by Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), which placed the orbits of all the planets (except Earth) around the sun – yet the orbits of the sun (and moon) around a stationary Earth.

It wasn’t until 1838 that Frederic Bessel (1784-1846) finally proved conclusively that the Earth orbits the sun when he successfully found the parallax of the star 61 Cygni in 1838.

Thus the phases of Venus provided visual evidence of Venus’ motion around the sun in Galileo’s time. Those changing phases – which amateur astronomers with small telescopes will be watching in the coming months – provided a first step in the long and arduous journey in humanity’s acceptance of a sun-centered solar system.

The model developed by Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) places Earth at the center of the cosmos, with all the planets (except Earth) revolving around the sun, yet the sun and moon revolving around a stationary Earth.

Bottom line: On February 27 and 28, 2020, look west after sunset for the waxing crescent moon and brilliant planet Venus. The planet Uranus will be lurking – mostly unseeen – nearby.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Ti2ZFD

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire