From the left, Gene Primaky, Jim Baichtal, and Patrick Druckenmiller at the excavation site of the new fossil in the Keku Islands of southeastern Alaska. It was just after they’d extracted the fossil, minutes before the site was submerged by a rising tide. “We rock-sawed like crazy and managed to pull it out,” Druckenmiller said. Image via Kevin May/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

In 2011, scientists worked against a rising tide to excavate a remarkable fossil on an island in southeast Alaska. Subsequent studies revealed that the fossil was a new species of thalattosaur, a marine reptile that lived more than 200 million years ago. This specimen has since been named Gunakadeit joseeae (pronounced ghu-nuh-kuh-DATE JOE-zee-ay; the first syllable’s vowel sounds like the “oo” in “good”). It’s the most complete thalattosaur skeleton ever found in North America and has added substantial new information to this little-known group of extinct reptiles.

Details of the discovery were published in the journal Scientific Reports on February 4, 2020.

It’s a wonder the fossil was ever found; the specimen was in an intertidal area at the Keku Islands, near the village of Kake. It was submerged most of the time, except during very low tides that happened for a few hours on only a few days of each year.

On one such occasion, on May 18, 2011, Jim Baichtal, a U.S. Forest Service geologist with the Tongass National Forest, was out hunting for fossils with colleagues. With him was Gene Primaky, an information technologist, who first spotted the fossil on a rocky outcrop.

Baichtal sent a photo of it to geologist Patrick Druckenmiller at the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

A month later, Druckenmiller and his team were on site to excavate the fossil. They had a narrow window for their work: two days when low tides were low enough, during daylight, to expose the fossil for about four hours on each day. The next opportunity would not come around for nearly another year. Druckenmiller said:

We rock-sawed like crazy and managed to pull it out, but just barely. The water was lapping at the edge of the site.

The fossil turned out to be a new thalattosaur species, now called Gunakadeit joseeae. The skeleton was fully intact, except for two-thirds of its tail that was lost to erosion. Image via University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Artist’s depiction of a single Gunakadeit joseeae. Image via Ray Troll/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

It took several years at the University of Alaska Museum of the North for a fossil preparation specialist to clean the specimen and prepare it for study.

The first indication that this was a new species of thalattosaur was the shape of the fossil’s skull. It had a very pointed snout, which Druckenmiller suggested was a likely adaptation to the shallow seas in which the animal once lived. He thinks that shape may have ultimately led to the demise of the species, saying:

It was probably poking its pointy schnoz into cracks and crevices in coral reefs and feeding on soft-bodied critters. We think these animals were highly specialized to feed in the shallow water environments, but when the sea levels dropped and food sources changed, they had nowhere to go.

Today, the name of the newly found creature reflects both the place where it was found, and its discovery story. The genus name, Gunakadeit, is that of a sea monster from the lore of the Tlingit people, who were indigenous to the Pacific Northwest of North America. The species name, joseeae, is in honor of Joseé Michelle DeWaelheyns, mother of the fossil’s discoverer, Gene Primaky.

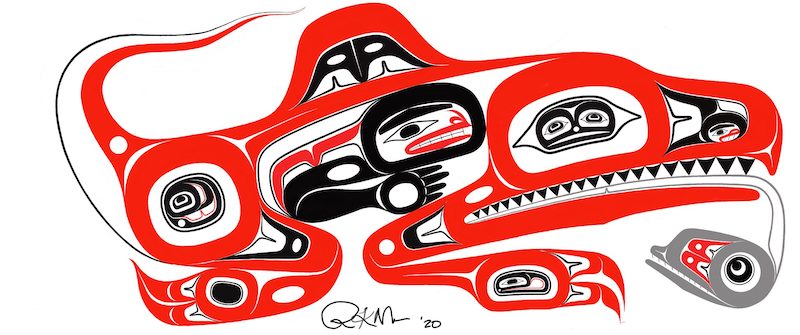

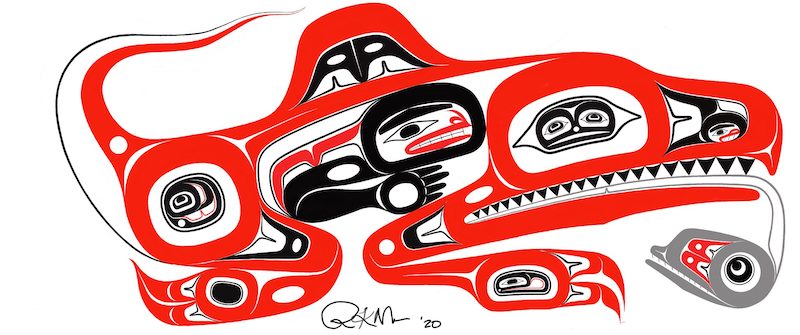

Artwork by Robert Mills ©2020. It depicts Gunakadeit, a creature of the lore of the Tlingit people of the Pacific Northwest. In Tlingit mythology, Gunakadeit is a sea monster that brings good luck to those who see it. Image via Robert Mills/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Thalattosaurs lived during the mid to late Triassic Period, about 247 to 201 million years ago. Found in tropical seas around the world, these marine reptiles reached lengths of 3 to 4 meters (10 to 13 feet). They became extinct at the end of the Triassic Period, about 201 million years ago.

Prior to the discovery of Gunakadeit joseeae, it had been 20 years since scientists had taken an exhaustive look at thalattosaurs. In paleontology, this involved studying the detailed anatomical characteristics of other thalattosaur fossils found around the world, and using computers to analyze the possible relationships between the different species. Patrick Druckenmiller, who led the study of this creature, said in a statement:

When you find a new species, one of the things you want to do is tell people where you think it fits in the family tree. We decided to start from scratch on the family tree.

In the study of living things, a “family tree” is a body of knowledge, represented as a diagram, that shows evolutionary relationships between related organisms, including their common ancestry.

Druckenmiller worked with Neil Kelley of Vanderbilt University on the analysis of the fossil’s place on the thalattosaur family tree. The results took them by surprise. Druckenmiller commented:

It was so specialized and weird, we thought it might be out at the furthest branches of the tree. Instead it’s a relatively primitive type of thalattosaur that survived late into the existence of the group.

Kelley added:

Thalattosaurs were among the first groups of land-dwelling reptiles to readapt to life in the ocean. They thrived for tens of millions of years, but their fossils are relatively rare so this new specimen helps fill an important gap in the story of their evolution and eventual extinction.

Artist’s depiction of the new thalattosaur species, Gunakadeit joseeae. It lived 200 million years ago. Image via Ray Troll/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Bottom line: Scientists have discovered a new species of thalattosaur, a marine reptile that lived more than 200 million years ago in warm tropical seas around the world. This specimen, named Gunakadeit joseeae, is the most intact North American thalattosaur ever found, and has helped scientists better understand how thalattosaur species are related to each other.

Via University of Alaska Fairbanks

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/39uukuW

From the left, Gene Primaky, Jim Baichtal, and Patrick Druckenmiller at the excavation site of the new fossil in the Keku Islands of southeastern Alaska. It was just after they’d extracted the fossil, minutes before the site was submerged by a rising tide. “We rock-sawed like crazy and managed to pull it out,” Druckenmiller said. Image via Kevin May/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

In 2011, scientists worked against a rising tide to excavate a remarkable fossil on an island in southeast Alaska. Subsequent studies revealed that the fossil was a new species of thalattosaur, a marine reptile that lived more than 200 million years ago. This specimen has since been named Gunakadeit joseeae (pronounced ghu-nuh-kuh-DATE JOE-zee-ay; the first syllable’s vowel sounds like the “oo” in “good”). It’s the most complete thalattosaur skeleton ever found in North America and has added substantial new information to this little-known group of extinct reptiles.

Details of the discovery were published in the journal Scientific Reports on February 4, 2020.

It’s a wonder the fossil was ever found; the specimen was in an intertidal area at the Keku Islands, near the village of Kake. It was submerged most of the time, except during very low tides that happened for a few hours on only a few days of each year.

On one such occasion, on May 18, 2011, Jim Baichtal, a U.S. Forest Service geologist with the Tongass National Forest, was out hunting for fossils with colleagues. With him was Gene Primaky, an information technologist, who first spotted the fossil on a rocky outcrop.

Baichtal sent a photo of it to geologist Patrick Druckenmiller at the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

A month later, Druckenmiller and his team were on site to excavate the fossil. They had a narrow window for their work: two days when low tides were low enough, during daylight, to expose the fossil for about four hours on each day. The next opportunity would not come around for nearly another year. Druckenmiller said:

We rock-sawed like crazy and managed to pull it out, but just barely. The water was lapping at the edge of the site.

The fossil turned out to be a new thalattosaur species, now called Gunakadeit joseeae. The skeleton was fully intact, except for two-thirds of its tail that was lost to erosion. Image via University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Artist’s depiction of a single Gunakadeit joseeae. Image via Ray Troll/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

It took several years at the University of Alaska Museum of the North for a fossil preparation specialist to clean the specimen and prepare it for study.

The first indication that this was a new species of thalattosaur was the shape of the fossil’s skull. It had a very pointed snout, which Druckenmiller suggested was a likely adaptation to the shallow seas in which the animal once lived. He thinks that shape may have ultimately led to the demise of the species, saying:

It was probably poking its pointy schnoz into cracks and crevices in coral reefs and feeding on soft-bodied critters. We think these animals were highly specialized to feed in the shallow water environments, but when the sea levels dropped and food sources changed, they had nowhere to go.

Today, the name of the newly found creature reflects both the place where it was found, and its discovery story. The genus name, Gunakadeit, is that of a sea monster from the lore of the Tlingit people, who were indigenous to the Pacific Northwest of North America. The species name, joseeae, is in honor of Joseé Michelle DeWaelheyns, mother of the fossil’s discoverer, Gene Primaky.

Artwork by Robert Mills ©2020. It depicts Gunakadeit, a creature of the lore of the Tlingit people of the Pacific Northwest. In Tlingit mythology, Gunakadeit is a sea monster that brings good luck to those who see it. Image via Robert Mills/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Thalattosaurs lived during the mid to late Triassic Period, about 247 to 201 million years ago. Found in tropical seas around the world, these marine reptiles reached lengths of 3 to 4 meters (10 to 13 feet). They became extinct at the end of the Triassic Period, about 201 million years ago.

Prior to the discovery of Gunakadeit joseeae, it had been 20 years since scientists had taken an exhaustive look at thalattosaurs. In paleontology, this involved studying the detailed anatomical characteristics of other thalattosaur fossils found around the world, and using computers to analyze the possible relationships between the different species. Patrick Druckenmiller, who led the study of this creature, said in a statement:

When you find a new species, one of the things you want to do is tell people where you think it fits in the family tree. We decided to start from scratch on the family tree.

In the study of living things, a “family tree” is a body of knowledge, represented as a diagram, that shows evolutionary relationships between related organisms, including their common ancestry.

Druckenmiller worked with Neil Kelley of Vanderbilt University on the analysis of the fossil’s place on the thalattosaur family tree. The results took them by surprise. Druckenmiller commented:

It was so specialized and weird, we thought it might be out at the furthest branches of the tree. Instead it’s a relatively primitive type of thalattosaur that survived late into the existence of the group.

Kelley added:

Thalattosaurs were among the first groups of land-dwelling reptiles to readapt to life in the ocean. They thrived for tens of millions of years, but their fossils are relatively rare so this new specimen helps fill an important gap in the story of their evolution and eventual extinction.

Artist’s depiction of the new thalattosaur species, Gunakadeit joseeae. It lived 200 million years ago. Image via Ray Troll/ University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Bottom line: Scientists have discovered a new species of thalattosaur, a marine reptile that lived more than 200 million years ago in warm tropical seas around the world. This specimen, named Gunakadeit joseeae, is the most intact North American thalattosaur ever found, and has helped scientists better understand how thalattosaur species are related to each other.

Via University of Alaska Fairbanks

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/39uukuW

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire