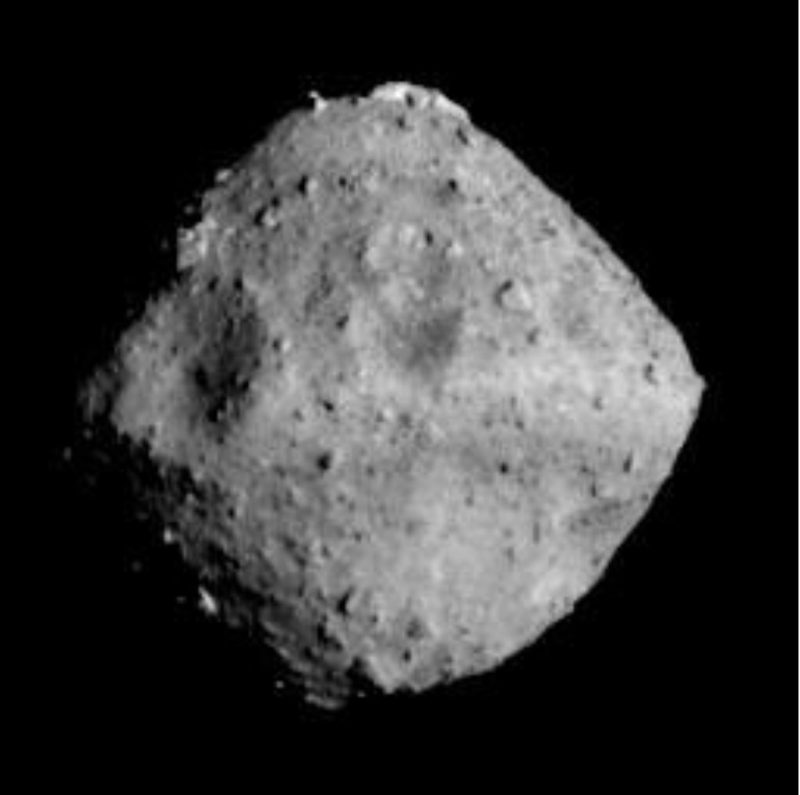

Here’s asteroid 162173 Ryugu in June 2018, as seen by Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft. This mission is the 2nd-ever sample-return mission to an asteroid. The earlier one was the original Hayabusa mission, which returned a sample from asteroid 25143 Itokawa in 2010. Image via the Japanese space agency, JAXA.

Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft – launched in December, 2014 – traveled some 200 million miles to near-Earth asteroid Ryugu. It closed to within 12 miles (20 km) of the asteroid’s surface in June 2018. Hayabusa2 will continue traveling with this asteroid until December 2019, when it’ll begin making its way back to Earth. It’s due to return a sample of the asteroid to scientists in December 2020. In the meantime – in two studies published this summer – the Hayabusa2 mission has already given us valuable information about asteroids like Ryugu. Among other things, it showed that, if an asteroid like Ryugu were headed toward Earth – and if we on Earth decided to send a spacecraft out in an attempt to divert the asteroid – we’d need to take “great care” in the attempt.

Hayabusa2 released several small rovers to Ryugu’s surface. One was a German-French device, called the Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout (MASCOT). It was “no bigger than a microwave oven” and equipped with four instruments. On October 3, 2018, MASCOT separated from Hayabusa2 when the craft was 41 meters (about 100 feet) above the asteroid. MASCOT touched down on Ryugu for the first time six minutes after deployment, bounced a bit in the asteroid’s low gravity, then settled on its surface about 11 minutes later.

Hello #Earth, hello @haya2kun! I promised to send you some pictures of #Ryugu so here’s a shot I took during my descent. Can you spot my shadow? #AsteroidLanding pic.twitter.com/dmcilFl5ms

— MASCOT Lander (@MASCOT2018) October 3, 2018

MASCOT lasted 17 hours on Ryugu, an hour longer than anticipated, until its non-rechargeable battery ran out. It carried out experiments in various places amid Ryugu’s large boulders, possible because MASCOT was designed to tumble to reposition itself.

Researchers learned Ryugu’s surface is dominated by two types of rock. They were surprised to find no evidence for fine-grained dust. They noted that millimeter-sized inclusions in the rocks are similar to those present in carbonaceous meteorites found on Earth. This group includes some of the most primitive known meteorites, some of which date back 4.5 billion years. In other words, these meteorites are some of the oldest stuff in our neighborhood of space, formed when our solar system was condensing solid material from its original primordial nebula of gas and dust.

Scientists knew thiz sort of meteorite was fragile. Hayabusa2 confirmed just how fragile this sort of material is.

Planetary researcher Ralf Jaumann from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin-Adlershof led a research team that analyzed MASCOT’s results. These scientists reported on their results in the August 23, 2019, issue of the peer-reviewed journal Science. Jaumann explained in a statement on August 22:

If Ryugu or another similar asteroid were ever to come dangerously close to Earth and an attempt had to be made to divert it, this would need to be done with great care. In the event that it was impacted with great force, the entire asteroid, weighing approximately half-a-billion tons, would break up into numerous fragments. Then, many individual parts weighing several tons would impact Earth.

Ryugu was found to have an average density of just 1.2 grams per cubic centimeter (.043 pounds per cubic inch). In other words, the asteroids is only a little “heavier” than water ice. But, the scientists said:

… as the asteroid is made up of numerous pieces of rock of different sizes, this means that much of its volume must be traversed by cavities, which probably makes this diamond-shaped body extremely fragile. This is also indicated by the measurements conducted by the DLR MASCOT Radiometer (MARA) experiment, which were published recently.

MASCOT’s descent and path across Ryugu, via DLR.

In that earlier study – published July 15 in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy – scientists using Hayabusa2 data to study Ryugu pointed out an upside to the asteroid’s fragility. Their statement on July 15 said:

Ryugu and other asteroids of the common ‘C-class’ consist of more porous material than was previously thought. Small fragments of their material are therefore too fragile to survive entry into the atmosphere in the event of a collision with Earth.

These two studies of asteroid Ryugu were made possible by a space mission that, like all space missions, required years for planning and implementation. Thanks to the mission, scientists learned that what we knew from Earth-based observations about the nature of these asteroids was essentially correct. But they confirmed and refined their knowledge; they know more details now.

Ryugu is what’s called a near-Earth object (NEO). That’s an asteroid or comet that comes close to or intersects Earth’s orbit.

Ryugu itself is not on a collision course with Earth and likely never will be. That’s good because Ryugu is 850 meters (about a half a mile) across, large enough to do some serious damage to any world it might strike. It could wipe out a city, for example. But, again, Ryugu isn’t going to strike us. In part because we sent a spacecraft to it, we know a lot about the orbit of this asteroid. Its orbit around the sun is almost coplanar to that of Earth. The asteroid approaches us at an angle of 5.9 degrees to within a distance of approximately 100,000 kilometers (60,000 miles). These scientists said:

Ryugu will never come within the immediate vicinity of Earth, but knowing the properties of bodies like Ryugu is of great importance when it comes to assessing how such near-Earth objects (NEOs) could be dealt with in the future.

Bottom line: Two studies published this summer about asteroid Ryugu – based on data from the Hayabusa2 mission – confirm that the asteroid is fragile, even more fragile than scientists had thought. The good news is that fragments of this asteroid (or asteroids like it) might more easily burn up in our atmosphere. The bad news is that, if an asteroid like this one were on a collision course with Earth, and we planned to try to divert it (for example, by setting off a nuclear device in its vicinity), we’d have to do so with “great care” in order not to create multiple large bodies that would then impact Earth. By the way, in case you’re interested, Hayabusa is Japanese for Peregrine falcon, which is Earth’s fastest bird.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2HWoKpC

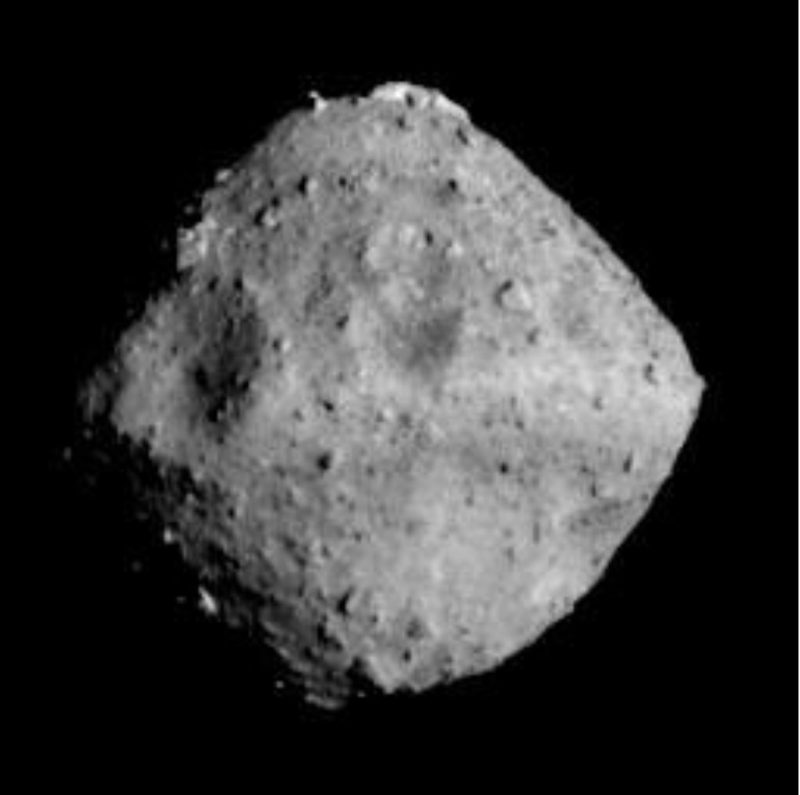

Here’s asteroid 162173 Ryugu in June 2018, as seen by Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft. This mission is the 2nd-ever sample-return mission to an asteroid. The earlier one was the original Hayabusa mission, which returned a sample from asteroid 25143 Itokawa in 2010. Image via the Japanese space agency, JAXA.

Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft – launched in December, 2014 – traveled some 200 million miles to near-Earth asteroid Ryugu. It closed to within 12 miles (20 km) of the asteroid’s surface in June 2018. Hayabusa2 will continue traveling with this asteroid until December 2019, when it’ll begin making its way back to Earth. It’s due to return a sample of the asteroid to scientists in December 2020. In the meantime – in two studies published this summer – the Hayabusa2 mission has already given us valuable information about asteroids like Ryugu. Among other things, it showed that, if an asteroid like Ryugu were headed toward Earth – and if we on Earth decided to send a spacecraft out in an attempt to divert the asteroid – we’d need to take “great care” in the attempt.

Hayabusa2 released several small rovers to Ryugu’s surface. One was a German-French device, called the Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout (MASCOT). It was “no bigger than a microwave oven” and equipped with four instruments. On October 3, 2018, MASCOT separated from Hayabusa2 when the craft was 41 meters (about 100 feet) above the asteroid. MASCOT touched down on Ryugu for the first time six minutes after deployment, bounced a bit in the asteroid’s low gravity, then settled on its surface about 11 minutes later.

Hello #Earth, hello @haya2kun! I promised to send you some pictures of #Ryugu so here’s a shot I took during my descent. Can you spot my shadow? #AsteroidLanding pic.twitter.com/dmcilFl5ms

— MASCOT Lander (@MASCOT2018) October 3, 2018

MASCOT lasted 17 hours on Ryugu, an hour longer than anticipated, until its non-rechargeable battery ran out. It carried out experiments in various places amid Ryugu’s large boulders, possible because MASCOT was designed to tumble to reposition itself.

Researchers learned Ryugu’s surface is dominated by two types of rock. They were surprised to find no evidence for fine-grained dust. They noted that millimeter-sized inclusions in the rocks are similar to those present in carbonaceous meteorites found on Earth. This group includes some of the most primitive known meteorites, some of which date back 4.5 billion years. In other words, these meteorites are some of the oldest stuff in our neighborhood of space, formed when our solar system was condensing solid material from its original primordial nebula of gas and dust.

Scientists knew thiz sort of meteorite was fragile. Hayabusa2 confirmed just how fragile this sort of material is.

Planetary researcher Ralf Jaumann from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin-Adlershof led a research team that analyzed MASCOT’s results. These scientists reported on their results in the August 23, 2019, issue of the peer-reviewed journal Science. Jaumann explained in a statement on August 22:

If Ryugu or another similar asteroid were ever to come dangerously close to Earth and an attempt had to be made to divert it, this would need to be done with great care. In the event that it was impacted with great force, the entire asteroid, weighing approximately half-a-billion tons, would break up into numerous fragments. Then, many individual parts weighing several tons would impact Earth.

Ryugu was found to have an average density of just 1.2 grams per cubic centimeter (.043 pounds per cubic inch). In other words, the asteroids is only a little “heavier” than water ice. But, the scientists said:

… as the asteroid is made up of numerous pieces of rock of different sizes, this means that much of its volume must be traversed by cavities, which probably makes this diamond-shaped body extremely fragile. This is also indicated by the measurements conducted by the DLR MASCOT Radiometer (MARA) experiment, which were published recently.

MASCOT’s descent and path across Ryugu, via DLR.

In that earlier study – published July 15 in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy – scientists using Hayabusa2 data to study Ryugu pointed out an upside to the asteroid’s fragility. Their statement on July 15 said:

Ryugu and other asteroids of the common ‘C-class’ consist of more porous material than was previously thought. Small fragments of their material are therefore too fragile to survive entry into the atmosphere in the event of a collision with Earth.

These two studies of asteroid Ryugu were made possible by a space mission that, like all space missions, required years for planning and implementation. Thanks to the mission, scientists learned that what we knew from Earth-based observations about the nature of these asteroids was essentially correct. But they confirmed and refined their knowledge; they know more details now.

Ryugu is what’s called a near-Earth object (NEO). That’s an asteroid or comet that comes close to or intersects Earth’s orbit.

Ryugu itself is not on a collision course with Earth and likely never will be. That’s good because Ryugu is 850 meters (about a half a mile) across, large enough to do some serious damage to any world it might strike. It could wipe out a city, for example. But, again, Ryugu isn’t going to strike us. In part because we sent a spacecraft to it, we know a lot about the orbit of this asteroid. Its orbit around the sun is almost coplanar to that of Earth. The asteroid approaches us at an angle of 5.9 degrees to within a distance of approximately 100,000 kilometers (60,000 miles). These scientists said:

Ryugu will never come within the immediate vicinity of Earth, but knowing the properties of bodies like Ryugu is of great importance when it comes to assessing how such near-Earth objects (NEOs) could be dealt with in the future.

Bottom line: Two studies published this summer about asteroid Ryugu – based on data from the Hayabusa2 mission – confirm that the asteroid is fragile, even more fragile than scientists had thought. The good news is that fragments of this asteroid (or asteroids like it) might more easily burn up in our atmosphere. The bad news is that, if an asteroid like this one were on a collision course with Earth, and we planned to try to divert it (for example, by setting off a nuclear device in its vicinity), we’d have to do so with “great care” in order not to create multiple large bodies that would then impact Earth. By the way, in case you’re interested, Hayabusa is Japanese for Peregrine falcon, which is Earth’s fastest bird.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2HWoKpC

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire