This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

John Kaiser wheeled a cart with a TV and VCR into the lobby of an academic building on the campus of the University of North Carolina-Wilmington, popped in a well-worn VHS cassette, and played a video extolling the virtues of an atmosphere rich in CO2.

“It was a video that was made to look like a news show; there were people who looked like anchors in it,” recalled Kaiser. It was part of a campaign to attract students to join a conservative movement on his undergraduate campus.

“[The video] was all about how CO2 levels are rising, but that’s great! Because plants need CO2, and the more CO2 there is, the more plants will grow and the more crops we’ll have. And the more we’ll have to eat and this will be an age of abundance because of all the extra CO2 in the atmosphere.”

Kaiser recounted the spin with a dash of wry humor, “So don’t worry about what the lefties and the liberals tell you, this is actually going to make things better.”

“I remember playing that video so many times,” he mused. Of all the types of information the group shared, this one garnered the most ardent pushback. Kaiser described a memorable instance when a challenger confronted him, “Do you realize the damage you’re doing peddling this s***?”

Kaiser’s confidence at the time was telling: “I was so certain in my convictions, that I said, ‘I’m not lying, you can see the citations in the video, right?’ But I didn’t realize the extent to which they were twisting the references they had. I mean, I was 19 years old, and the video confirmed what I already believed, and so my confirmation bias was really strong at that moment. I didn’t have enough experience to overcome it. I’m ashamed I believed this stuff.”

That was in 1999. Over the course of about 12 years, Kaiser made the switch from a student activist eager to sow doubt about climate change, to someone who is worried about the impacts of climate change. He has confronted his own role in delaying action, and is motivated to share his story. One way he does so is through Facebook comments, where he describes himself as a “former denier” and explains his subsequent change of thinking.

After reading Kaiser’s online comments, I sought him out to learn more about his evolution and see what insights he had to offer. Kaiser shared his story during a lively video call.

A home-grown conservative, turned college professor

Kaiser grew up on Long Island and moved to North Carolina as a teen. “My father was fundamentalist, in his religion and politics,” recalled Kaiser, and right-wing political talk shows were a constant presence in his upbringing. “[My father] had one of those sound systems wired into the house. So you could hear it wherever you went in the house or in the yard, you’d have Rush Limbaugh playing in the background.”

“I remember trying to call into the Rush Limbaugh show so many times, but I could never get through,” Kaiser said, chuckling at his younger self. “It was part of my formative teenage memories.”

Kaiser exudes a knack for storytelling, speaking with the rapid-fire fluidity of a stand-up comic, with a dose of Long Island accent and only an occasional pause for a breath or a self-deprecating laugh. He’s immediately likeable.

Now a history professor at a two-year college in the Southeast, Kaiser’s students describe him as “hilarious” with “amazing lectures.” One student wrote on Rate My Professor, “Dr. Kaiser doesn’t just teach history; he performs it as if he is on a stage.” As Kaiser chronicled his own personal history, it was easy to see why he’s popular with students. His narrative came alive with humor and humility as he explained “how wrongheaded but certain I once was.”

A well-trained student leader

When he left home and went to college, Kaiser said, his views surged further to the right. “I think it would be accurate to describe myself as kind of an Evangelical fundamentalist at the time.” Kaiser joined a conservative group called the Leadership Institute, which trains students to become effective in political engagement. “They would give us all kinds of stuff for how to talk about climate change,” he recalled, “in a way that advances the agenda of the political right.”

“At that time in my life I envisioned that I was going to become some kind of political operative,” he said.

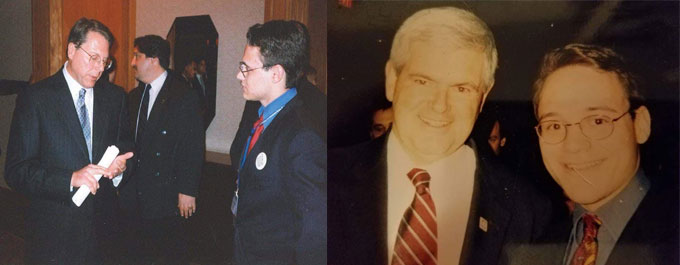

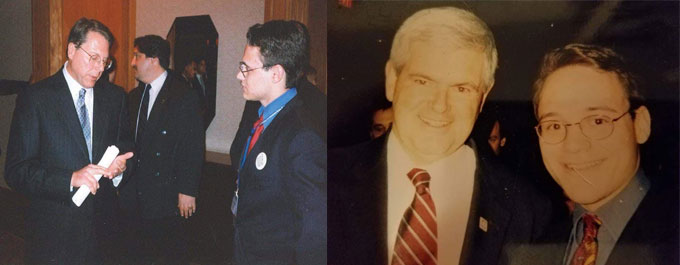

A young John Kaiser with NRA gun rights activist Wayne LaPierre, left, and former Republican Congressman Newt Gingrich, right.

A young John Kaiser with NRA gun rights activist Wayne LaPierre, left, and former Republican Congressman Newt Gingrich, right.

Kaiser became heavily involved with the Leadership Institute, attending training events, meeting conservative icons, and learning the ropes as a political organizer, all paid for by the institute. “They would be quite disappointed in how I turned out,” mused Kaiser.

Fear of government intervention underlies resistance on climate change

Kaiser sums up the primary reason he and other conservatives rejected the premise of climate change: “Because if climate change is as bad as they say it is, it would justify government intervention. And we can’t justify government intervention because that’s a bad thing.”

Climate change was viewed as a power grab: “This is how the government was going to trick us into giving our rights away and fully regulate the economy to protect the environment.” He recited the rationale with uncanny polish. “I still remember making that argument myself as a college student.”

He elaborated, “I think a lot of people on the right do what I did, which is that we work backwards from an ideological fear of government intervention to the idea that we can’t accept climate change.”

“God forbid there be global solutions to things that are literally global problems,” he added with sarcasm.

When asked if anything – any piece of evidence or persuasive tactic – could have changed his mind, Kaiser let out a drawn-out, pensive sigh. “At that time? No,” he admitted flatly. “I really had to experience the process of maturing and encountering not just new ideas on climate change, but new ideas that challenged my entire worldview.”

Changing views

By the time Kaiser was part way through his PhD program in history at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, his views began to shift. He was in his late 20s, and his education and exposure to details of American history led to eventual initial cracks in his hardline stance. “There were things that were part of my fundamentalist upbringing that I questioned,” he said.

“You’ve probably followed the polling that says that the majority of Republicans are now fearful that advanced education is dangerous,” he said. “And I think my experience is kind of what they fear.”

“Looking back, I think the very first issue that got me moving away [from a conservative viewpoint], was the debate about gay marriage. That was the one where I got fed up with a lot of the people I knew on the right. And then I got angry about the drug war debates. And that got me fed up even more with people on the right. And it was just kind of like this snowball rolling downhill that picked up steam. And I just kept finding all of these issues where I said, well now I’m seeing the evidence points this way, but I had believed the opposite.”

As effective communicators already know, values lie at the heart of people’s views and attitudes. Changing these values is not a simple process. “As I look back on it, it’s incredibly complex,” recalled Kaiser. “The way our identities work, it’s like a jigsaw puzzle. You take one piece out and you just can’t put another piece in. So you have to rearrange the entire thing, or it just doesn’t fit anymore. So it was very odd, I was replacing these little pieces on gay marriage, on climate change, and suddenly my puzzle didn’t work. I realized I’m looking at the wrong puzzle. I have to go get a different box – a whole different puzzle.”

“Climate change went along with those beliefs,” he said. “I never quite believed it was a hoax like [President] Trump likes to say, but I kind of took the position that what if they’re just wrong about what the outcome is going to be.”

“So I wasn’t out there denying the temperature indications. I wasn’t out there denying CO2 levels. I was denying the consequences of them.”

“And that denial stopped in 2009 or 2010. I really kind of shifted significantly.”

‘I should have looked more deeply’

Kaiser says he now is motivated to publicly share his turnabout on climate change. “I just feel guilty that my generation was part of setting up the politics of today. That we played a role in spreading misinformation. That we were unwitting allies of merchants of doubt …. We didn’t realize that coal companies and oil companies were funding all of these things we were showing about the positive benefits of CO2.”

“I do feel some responsibility that I should have known better, that I should have looked more deeply into the issue, into who was funding the stuff that I was putting out there.”

“If I can do something to remedy it, it would be a good penance,” he had written to me prior to our interview. In that vein, Kaiser offers four takeaways drawn from his former role as a spokesperson against climate action.

1. Make it personal and local.

“So much of what you … care about, when you’re conservative, relates to the people who are in your circle,” explained Kaiser. “If you know people who are in your circle who are gay, well then you’re going to be more forgiving or more open on the gay marriage issue.”

“Maybe when climate change starts affecting their hometown, that’s when they’re going to accept it because that just seems to be ingrained within conservatism, that it has to be something that I can feel locally in my community. I think one of the quintessential aspects of conservatism is a distrust of outsiders.”

“[Climate change] has now suddenly become personal and so you can push the [conservative] ideology aside a little bit to actually address it because you are willing to trust and accept that it’s happening. Because now you’re getting testimony from the inside.”

2. Solutions needn’t come from ‘government overreach.’

Kaiser emphasized how disdain for government policies had been the underpinning of his climate denial. Accordingly, he explained how these concerns can be eased by emphasizing the role of private markets in brokering control strategies. “Convince them [conservatives] that there’s a way for private business to solve it. If there’s a dollar to be made in it, and you can promise them the government’s not going to be regulating things to do it, they’ll back it.”

“I know there are climate change embracers on the political right, but almost every one I’ve seen is offering a private free-market solution. That’s what gives them the wiggle room to go out and say, ‘Look, I accept climate change, I just don’t accept government intervention to address it.'”

Whether free-market solutions are sufficient is an important caveat to this strategy, but Kaiser’s advice may at least bring people to the table. Many corporations recognize the benefits of lowering emissions and are taking significant steps to do so. Low prices on renewable energy can appeal to any capitalist, and progress can be made right away, without wrestling with any legislative or regulatory process.

3. Find Republicans who accept climate change.

In these polarizing times, information from outside one’s own bubble often is unceremoniously dismissed. That’s why a trusted messenger is a powerful voice.

“You need those people who are straight down the list Republicans, except, oh, you need to address climate change. Those people get some wiggle room. They get the ability to talk and be a little bit ‘off’ on that topic, because they can check all the other boxes.”

Kaiser appreciates the irony of this advice. “I almost feel like I’ve done the wrong thing, by moving so far away [ideologically]. Because now when I talk about climate change, I’m an outsider.”

4. Leverage the economics of renewable energy.

Energy lies at the heart of climate change, and Kaiser acknowledges it’s similarly polarizing. “There’s an attempt now to make coal the new apple pie. That it’s being blended into patriotism, that you have to love and support coal.”

“It’s tough love for your lungs,” he laughed.

Kaiser suggests shifting to a strictly economics-based argument. “If you want to move people quickly in the next five to 10 years, it’s probably easier to present an argument that solar and wind energy are now entirely viable than it is to present an argument that climate change is real and we need to address it.”

What? Me worry? Yes … ‘thought horrifies me … I worry’

Kaiser reflects on his contributions to stall action on climate change, and grapples with the implications for the future. “Now I’m a 39-year-old man with children who are going to reach maturity … in a world that will be worse than the one that I came to maturity in. That thought horrifies me, especially because I was out there on a weekly basis telling people, don’t worry about global warming, it’s not going to be a problem.”

“I’d like to say that there’s a part of me that believes that, politically and technologically, we will figure this out in time. And that the technology of geothermal, solar, wind, all of that, will advance … to fully replace coal, and a big chunk of oil. There’s a part of me that wants to believe that. But, having been a part of climate change denial, I worry about whether we can get to that point. And I worry especially as we see active attempts at sabotaging things like renewable energy industries.”

“Time will tell, we will see. I worry that it won’t be enough.”

from Skeptical Science http://bit.ly/2YlhlWy

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

John Kaiser wheeled a cart with a TV and VCR into the lobby of an academic building on the campus of the University of North Carolina-Wilmington, popped in a well-worn VHS cassette, and played a video extolling the virtues of an atmosphere rich in CO2.

“It was a video that was made to look like a news show; there were people who looked like anchors in it,” recalled Kaiser. It was part of a campaign to attract students to join a conservative movement on his undergraduate campus.

“[The video] was all about how CO2 levels are rising, but that’s great! Because plants need CO2, and the more CO2 there is, the more plants will grow and the more crops we’ll have. And the more we’ll have to eat and this will be an age of abundance because of all the extra CO2 in the atmosphere.”

Kaiser recounted the spin with a dash of wry humor, “So don’t worry about what the lefties and the liberals tell you, this is actually going to make things better.”

“I remember playing that video so many times,” he mused. Of all the types of information the group shared, this one garnered the most ardent pushback. Kaiser described a memorable instance when a challenger confronted him, “Do you realize the damage you’re doing peddling this s***?”

Kaiser’s confidence at the time was telling: “I was so certain in my convictions, that I said, ‘I’m not lying, you can see the citations in the video, right?’ But I didn’t realize the extent to which they were twisting the references they had. I mean, I was 19 years old, and the video confirmed what I already believed, and so my confirmation bias was really strong at that moment. I didn’t have enough experience to overcome it. I’m ashamed I believed this stuff.”

That was in 1999. Over the course of about 12 years, Kaiser made the switch from a student activist eager to sow doubt about climate change, to someone who is worried about the impacts of climate change. He has confronted his own role in delaying action, and is motivated to share his story. One way he does so is through Facebook comments, where he describes himself as a “former denier” and explains his subsequent change of thinking.

After reading Kaiser’s online comments, I sought him out to learn more about his evolution and see what insights he had to offer. Kaiser shared his story during a lively video call.

A home-grown conservative, turned college professor

Kaiser grew up on Long Island and moved to North Carolina as a teen. “My father was fundamentalist, in his religion and politics,” recalled Kaiser, and right-wing political talk shows were a constant presence in his upbringing. “[My father] had one of those sound systems wired into the house. So you could hear it wherever you went in the house or in the yard, you’d have Rush Limbaugh playing in the background.”

“I remember trying to call into the Rush Limbaugh show so many times, but I could never get through,” Kaiser said, chuckling at his younger self. “It was part of my formative teenage memories.”

Kaiser exudes a knack for storytelling, speaking with the rapid-fire fluidity of a stand-up comic, with a dose of Long Island accent and only an occasional pause for a breath or a self-deprecating laugh. He’s immediately likeable.

Now a history professor at a two-year college in the Southeast, Kaiser’s students describe him as “hilarious” with “amazing lectures.” One student wrote on Rate My Professor, “Dr. Kaiser doesn’t just teach history; he performs it as if he is on a stage.” As Kaiser chronicled his own personal history, it was easy to see why he’s popular with students. His narrative came alive with humor and humility as he explained “how wrongheaded but certain I once was.”

A well-trained student leader

When he left home and went to college, Kaiser said, his views surged further to the right. “I think it would be accurate to describe myself as kind of an Evangelical fundamentalist at the time.” Kaiser joined a conservative group called the Leadership Institute, which trains students to become effective in political engagement. “They would give us all kinds of stuff for how to talk about climate change,” he recalled, “in a way that advances the agenda of the political right.”

“At that time in my life I envisioned that I was going to become some kind of political operative,” he said.

A young John Kaiser with NRA gun rights activist Wayne LaPierre, left, and former Republican Congressman Newt Gingrich, right.

A young John Kaiser with NRA gun rights activist Wayne LaPierre, left, and former Republican Congressman Newt Gingrich, right.

Kaiser became heavily involved with the Leadership Institute, attending training events, meeting conservative icons, and learning the ropes as a political organizer, all paid for by the institute. “They would be quite disappointed in how I turned out,” mused Kaiser.

Fear of government intervention underlies resistance on climate change

Kaiser sums up the primary reason he and other conservatives rejected the premise of climate change: “Because if climate change is as bad as they say it is, it would justify government intervention. And we can’t justify government intervention because that’s a bad thing.”

Climate change was viewed as a power grab: “This is how the government was going to trick us into giving our rights away and fully regulate the economy to protect the environment.” He recited the rationale with uncanny polish. “I still remember making that argument myself as a college student.”

He elaborated, “I think a lot of people on the right do what I did, which is that we work backwards from an ideological fear of government intervention to the idea that we can’t accept climate change.”

“God forbid there be global solutions to things that are literally global problems,” he added with sarcasm.

When asked if anything – any piece of evidence or persuasive tactic – could have changed his mind, Kaiser let out a drawn-out, pensive sigh. “At that time? No,” he admitted flatly. “I really had to experience the process of maturing and encountering not just new ideas on climate change, but new ideas that challenged my entire worldview.”

Changing views

By the time Kaiser was part way through his PhD program in history at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, his views began to shift. He was in his late 20s, and his education and exposure to details of American history led to eventual initial cracks in his hardline stance. “There were things that were part of my fundamentalist upbringing that I questioned,” he said.

“You’ve probably followed the polling that says that the majority of Republicans are now fearful that advanced education is dangerous,” he said. “And I think my experience is kind of what they fear.”

“Looking back, I think the very first issue that got me moving away [from a conservative viewpoint], was the debate about gay marriage. That was the one where I got fed up with a lot of the people I knew on the right. And then I got angry about the drug war debates. And that got me fed up even more with people on the right. And it was just kind of like this snowball rolling downhill that picked up steam. And I just kept finding all of these issues where I said, well now I’m seeing the evidence points this way, but I had believed the opposite.”

As effective communicators already know, values lie at the heart of people’s views and attitudes. Changing these values is not a simple process. “As I look back on it, it’s incredibly complex,” recalled Kaiser. “The way our identities work, it’s like a jigsaw puzzle. You take one piece out and you just can’t put another piece in. So you have to rearrange the entire thing, or it just doesn’t fit anymore. So it was very odd, I was replacing these little pieces on gay marriage, on climate change, and suddenly my puzzle didn’t work. I realized I’m looking at the wrong puzzle. I have to go get a different box – a whole different puzzle.”

“Climate change went along with those beliefs,” he said. “I never quite believed it was a hoax like [President] Trump likes to say, but I kind of took the position that what if they’re just wrong about what the outcome is going to be.”

“So I wasn’t out there denying the temperature indications. I wasn’t out there denying CO2 levels. I was denying the consequences of them.”

“And that denial stopped in 2009 or 2010. I really kind of shifted significantly.”

‘I should have looked more deeply’

Kaiser says he now is motivated to publicly share his turnabout on climate change. “I just feel guilty that my generation was part of setting up the politics of today. That we played a role in spreading misinformation. That we were unwitting allies of merchants of doubt …. We didn’t realize that coal companies and oil companies were funding all of these things we were showing about the positive benefits of CO2.”

“I do feel some responsibility that I should have known better, that I should have looked more deeply into the issue, into who was funding the stuff that I was putting out there.”

“If I can do something to remedy it, it would be a good penance,” he had written to me prior to our interview. In that vein, Kaiser offers four takeaways drawn from his former role as a spokesperson against climate action.

1. Make it personal and local.

“So much of what you … care about, when you’re conservative, relates to the people who are in your circle,” explained Kaiser. “If you know people who are in your circle who are gay, well then you’re going to be more forgiving or more open on the gay marriage issue.”

“Maybe when climate change starts affecting their hometown, that’s when they’re going to accept it because that just seems to be ingrained within conservatism, that it has to be something that I can feel locally in my community. I think one of the quintessential aspects of conservatism is a distrust of outsiders.”

“[Climate change] has now suddenly become personal and so you can push the [conservative] ideology aside a little bit to actually address it because you are willing to trust and accept that it’s happening. Because now you’re getting testimony from the inside.”

2. Solutions needn’t come from ‘government overreach.’

Kaiser emphasized how disdain for government policies had been the underpinning of his climate denial. Accordingly, he explained how these concerns can be eased by emphasizing the role of private markets in brokering control strategies. “Convince them [conservatives] that there’s a way for private business to solve it. If there’s a dollar to be made in it, and you can promise them the government’s not going to be regulating things to do it, they’ll back it.”

“I know there are climate change embracers on the political right, but almost every one I’ve seen is offering a private free-market solution. That’s what gives them the wiggle room to go out and say, ‘Look, I accept climate change, I just don’t accept government intervention to address it.'”

Whether free-market solutions are sufficient is an important caveat to this strategy, but Kaiser’s advice may at least bring people to the table. Many corporations recognize the benefits of lowering emissions and are taking significant steps to do so. Low prices on renewable energy can appeal to any capitalist, and progress can be made right away, without wrestling with any legislative or regulatory process.

3. Find Republicans who accept climate change.

In these polarizing times, information from outside one’s own bubble often is unceremoniously dismissed. That’s why a trusted messenger is a powerful voice.

“You need those people who are straight down the list Republicans, except, oh, you need to address climate change. Those people get some wiggle room. They get the ability to talk and be a little bit ‘off’ on that topic, because they can check all the other boxes.”

Kaiser appreciates the irony of this advice. “I almost feel like I’ve done the wrong thing, by moving so far away [ideologically]. Because now when I talk about climate change, I’m an outsider.”

4. Leverage the economics of renewable energy.

Energy lies at the heart of climate change, and Kaiser acknowledges it’s similarly polarizing. “There’s an attempt now to make coal the new apple pie. That it’s being blended into patriotism, that you have to love and support coal.”

“It’s tough love for your lungs,” he laughed.

Kaiser suggests shifting to a strictly economics-based argument. “If you want to move people quickly in the next five to 10 years, it’s probably easier to present an argument that solar and wind energy are now entirely viable than it is to present an argument that climate change is real and we need to address it.”

What? Me worry? Yes … ‘thought horrifies me … I worry’

Kaiser reflects on his contributions to stall action on climate change, and grapples with the implications for the future. “Now I’m a 39-year-old man with children who are going to reach maturity … in a world that will be worse than the one that I came to maturity in. That thought horrifies me, especially because I was out there on a weekly basis telling people, don’t worry about global warming, it’s not going to be a problem.”

“I’d like to say that there’s a part of me that believes that, politically and technologically, we will figure this out in time. And that the technology of geothermal, solar, wind, all of that, will advance … to fully replace coal, and a big chunk of oil. There’s a part of me that wants to believe that. But, having been a part of climate change denial, I worry about whether we can get to that point. And I worry especially as we see active attempts at sabotaging things like renewable energy industries.”

“Time will tell, we will see. I worry that it won’t be enough.”

from Skeptical Science http://bit.ly/2YlhlWy

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire