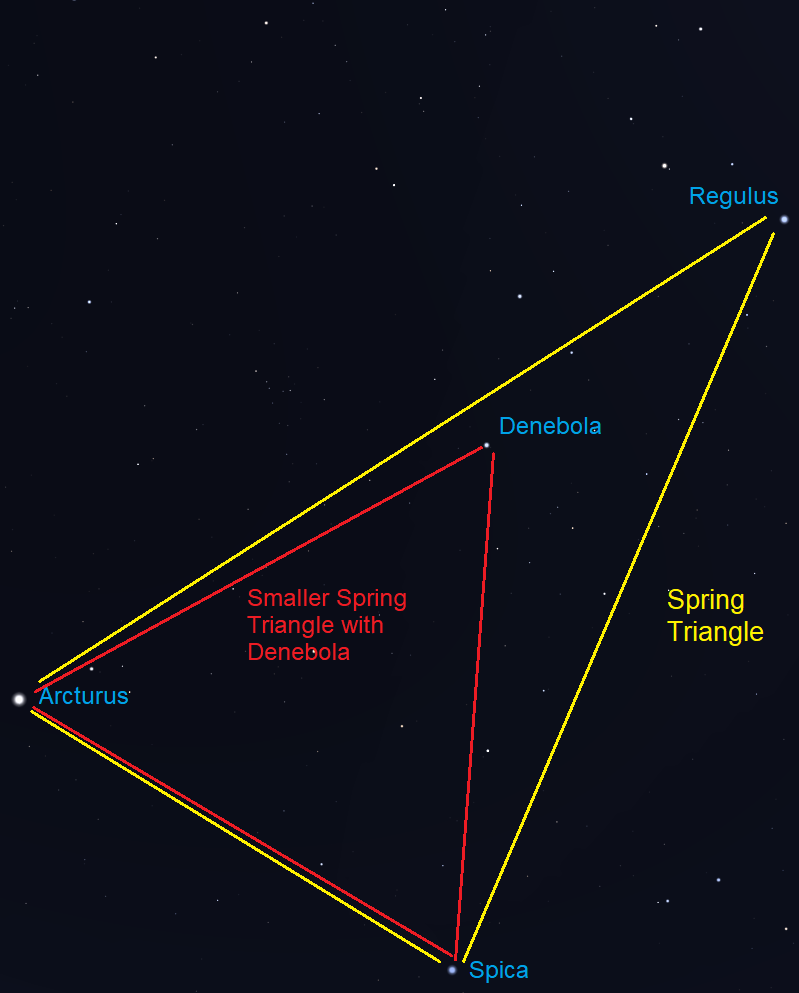

The Spring Triangle is an asterism with the bright stars Arcturus, Spica and Regulus at its corners. All 3 stars are in different constellations. Image via Scott Levine.

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

The Spring Triangle is a broad but unassuming triangle of three bright stars in three constellations. It starts to show its face on these cold midwinter nights.

Just as – a few weeks ago – the groundhog brought us into February and gave us hope for warmer weather, so the stars of the Spring Triangle start to make their way into the late evening sky as February progresses. By early March, these stars are all up before midnight. By early April, they’re all up by mid-evening (midway between sundown and midnight). When you see the Spring Triangle stars above the houses across the street, you can almost feel the warm springtime air.

The Spring Triangle, like the sky’s other seasonal shapes (for instance the Summer Triangle and Winter Circle (or Hexagon) isn’t a constellation. It isn’t one of the 88 regions of the sky officially recognized as constellations by the International Astronomical Union. Instead, it’s an asterism, an unofficial but recognizable pattern of stars that can be in one or more than one constellation. Asterisms are what many of us would pick out as constellations, if we didn’t know any. They’re often the sky’s most recognizable patterns.

The Spring Triangle is made up of three of the sky’s brightest stars in three different constellations: Regulus in Leo the Lion, Arcturus in Boötes the Herdsman (the only constellation with an umlaut in its name), and Spica in Virgo the Maiden.

Let’s learn to track these stars down so we can watch them move across the night as we wait for spring to begin.

You’ll know you’ve got the right 3 stars if you see the backwards question mark pattern – another asterism, called The Sickle in Leo – extending from the westernmost bright star, Regulus. Image via Scott Levine.

Once darkness falls in February, turn toward the east to find a bright yellowish star twinkling in the darkness. That’s Regulus, the first to rise of the three Spring Triangle stars. We see Regulus as one star, but it’s actually a four-star system. From about 79 light-years away, the light from the four blends into just one point in the night. The brightest star in this system is a yellow supergiant about three times the size of our sun.

If your skies are clear, you should be able to make out the backwards question mark pattern in Leo. This is another asterism, called The Sickle. It marks the Lion’s front end, while Regulus represents Leo’s heart. For an illustration, see the chart above.

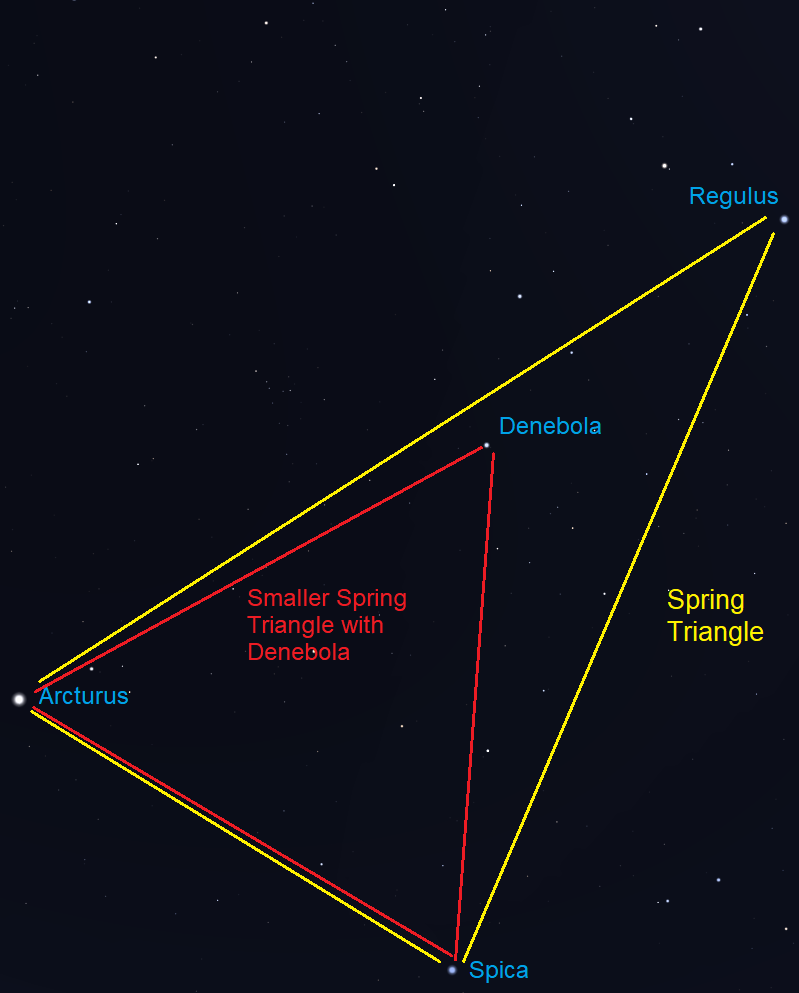

Also, notice that there’s a second Triangle inside the larger Spring Triangle. The smaller Triangle excludes Regulus, but includes yellowish Denebola, a double star about 36 light-years away. Denebola is the second brightest in Leo. It lies in the Lion’s tail. To see this second Triangle, see the chart below.

Some stargazers speak of the Spring Triangle as including Denebola instead of Regulus. Image via Scott Levine.

As the night goes on, Arcturus and Spica rise. In early March, all three stars – Arcturus, Spica and Regulus – will be up before midnight.

For those at northerly latitudes, Arcturus is the second-brightest star visible, after Sirius (those at more southerly latitudes, like the southern U.S., can see the sky’s actual second-brightest star, Canopus). Arcturus is a gorgeous old red giant about 37 light-years away. Billions of years from now, when the sun has burnt up its own hydrogen fuel supply, it will turn into a star similar to the type Arcturus is now.

If Arcturus has risen, chances are Spica has, too. Look for Spica lower in the sky than Arcturus – and father toward the south, or left – of the others. Spica is a blue giant star about 250 light-years away.

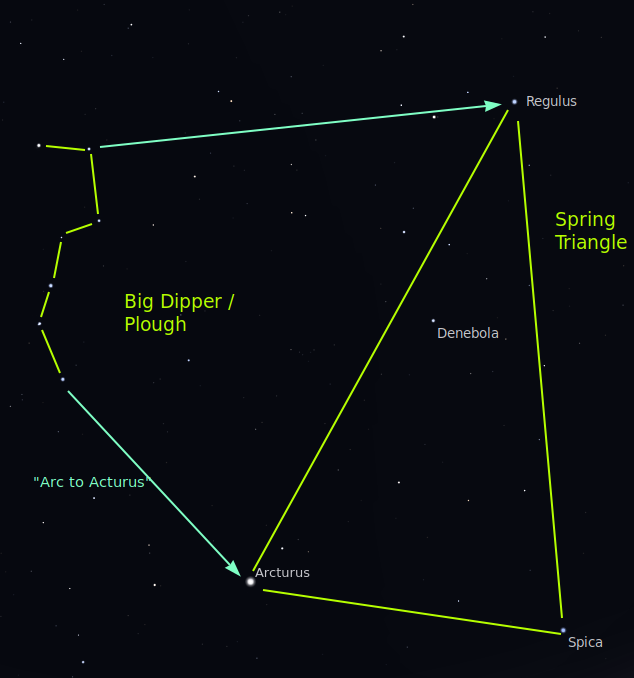

The Spring Triangle is less attention-grabbing than the Winter Circle (or Hexagon) and the Summer Triangle. If you’re having trouble finding it, there’s another way.

Use the Big Dipper (Plough) for extra help

Toward the north, look for the Big Dipper, called the Plough in the U.K. This time of year, by mid-evening, it’s ascending in the northeast. If you draw a line from the star Dubhe to the star Merak, the two stars at the end of the Dipper’s bowl or blade, and extend it toward the south, you’ll reach Regulus.

Also, if you follow the curve of the Dipper’s handle away from the bowl, you can follow the arc to Arcturus. From there, keep going, and drive a spike to Spica.

Surprisingly enough, the Spring Triangle is bigger than its more famous summertime cousin, and it’s almost as big across as the Winter Hexagon. It’s not one of the best-known star patterns, though.

Once you’ve found the Spring Triangle, you’ll enjoy it year after year. Maybe because it appears as spring is about to arrive, this pattern seems full of optimism for good things to come!

Bottom Line: See if you can find the Spring Triangle on these midwinter nights. It’ll start rising into the east as night falls in February and will stay around for most of the night until the summertime heat comes along.

Read more: Arc to Arcturus, the springtime star

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2TdHPdH

The Spring Triangle is an asterism with the bright stars Arcturus, Spica and Regulus at its corners. All 3 stars are in different constellations. Image via Scott Levine.

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

The Spring Triangle is a broad but unassuming triangle of three bright stars in three constellations. It starts to show its face on these cold midwinter nights.

Just as – a few weeks ago – the groundhog brought us into February and gave us hope for warmer weather, so the stars of the Spring Triangle start to make their way into the late evening sky as February progresses. By early March, these stars are all up before midnight. By early April, they’re all up by mid-evening (midway between sundown and midnight). When you see the Spring Triangle stars above the houses across the street, you can almost feel the warm springtime air.

The Spring Triangle, like the sky’s other seasonal shapes (for instance the Summer Triangle and Winter Circle (or Hexagon) isn’t a constellation. It isn’t one of the 88 regions of the sky officially recognized as constellations by the International Astronomical Union. Instead, it’s an asterism, an unofficial but recognizable pattern of stars that can be in one or more than one constellation. Asterisms are what many of us would pick out as constellations, if we didn’t know any. They’re often the sky’s most recognizable patterns.

The Spring Triangle is made up of three of the sky’s brightest stars in three different constellations: Regulus in Leo the Lion, Arcturus in Boötes the Herdsman (the only constellation with an umlaut in its name), and Spica in Virgo the Maiden.

Let’s learn to track these stars down so we can watch them move across the night as we wait for spring to begin.

You’ll know you’ve got the right 3 stars if you see the backwards question mark pattern – another asterism, called The Sickle in Leo – extending from the westernmost bright star, Regulus. Image via Scott Levine.

Once darkness falls in February, turn toward the east to find a bright yellowish star twinkling in the darkness. That’s Regulus, the first to rise of the three Spring Triangle stars. We see Regulus as one star, but it’s actually a four-star system. From about 79 light-years away, the light from the four blends into just one point in the night. The brightest star in this system is a yellow supergiant about three times the size of our sun.

If your skies are clear, you should be able to make out the backwards question mark pattern in Leo. This is another asterism, called The Sickle. It marks the Lion’s front end, while Regulus represents Leo’s heart. For an illustration, see the chart above.

Also, notice that there’s a second Triangle inside the larger Spring Triangle. The smaller Triangle excludes Regulus, but includes yellowish Denebola, a double star about 36 light-years away. Denebola is the second brightest in Leo. It lies in the Lion’s tail. To see this second Triangle, see the chart below.

Some stargazers speak of the Spring Triangle as including Denebola instead of Regulus. Image via Scott Levine.

As the night goes on, Arcturus and Spica rise. In early March, all three stars – Arcturus, Spica and Regulus – will be up before midnight.

For those at northerly latitudes, Arcturus is the second-brightest star visible, after Sirius (those at more southerly latitudes, like the southern U.S., can see the sky’s actual second-brightest star, Canopus). Arcturus is a gorgeous old red giant about 37 light-years away. Billions of years from now, when the sun has burnt up its own hydrogen fuel supply, it will turn into a star similar to the type Arcturus is now.

If Arcturus has risen, chances are Spica has, too. Look for Spica lower in the sky than Arcturus – and father toward the south, or left – of the others. Spica is a blue giant star about 250 light-years away.

The Spring Triangle is less attention-grabbing than the Winter Circle (or Hexagon) and the Summer Triangle. If you’re having trouble finding it, there’s another way.

Use the Big Dipper (Plough) for extra help

Toward the north, look for the Big Dipper, called the Plough in the U.K. This time of year, by mid-evening, it’s ascending in the northeast. If you draw a line from the star Dubhe to the star Merak, the two stars at the end of the Dipper’s bowl or blade, and extend it toward the south, you’ll reach Regulus.

Also, if you follow the curve of the Dipper’s handle away from the bowl, you can follow the arc to Arcturus. From there, keep going, and drive a spike to Spica.

Surprisingly enough, the Spring Triangle is bigger than its more famous summertime cousin, and it’s almost as big across as the Winter Hexagon. It’s not one of the best-known star patterns, though.

Once you’ve found the Spring Triangle, you’ll enjoy it year after year. Maybe because it appears as spring is about to arrive, this pattern seems full of optimism for good things to come!

Bottom Line: See if you can find the Spring Triangle on these midwinter nights. It’ll start rising into the east as night falls in February and will stay around for most of the night until the summertime heat comes along.

Read more: Arc to Arcturus, the springtime star

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2TdHPdH

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire