Michael Peres uses a black velvet catch tray to capture falling snowflakes. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Michael Peres is a professor of biomedical photographic communications at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. He’s also an award-winning photo-educator, author, and science photographer, with work featured by CNN, Time, the Weather Channel, Nikon, and Mashable. EarthSky spoke with him via email in January, 2019, to learn more about his amazing photographs.

How did you get interested in photographing snowflakes?

In the winter of 2003–2004, one of my students visited an exhibition of Wilson Snowflake Bentley photographs on display at the Buffalo Museum and Science Center. Her excitement about trying to photograph snowflakes was contagious and within a short period of time on a wintry day in January, my microscopy class moved our gear outside and we tried. Little did I know how infectious the experience would be for me personally. Now, more than 15 years later, I am obsessed with the challenge during the long and snowy Rochester, New York, winters. Rochester on average can receive more than 105 inches of snow per season. One could speculate that amount of snow would provide ample subjects and chances to photograph unique and interesting ice crystals.

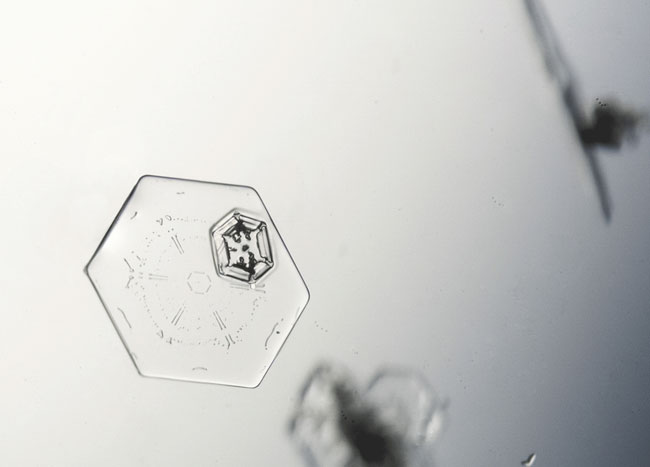

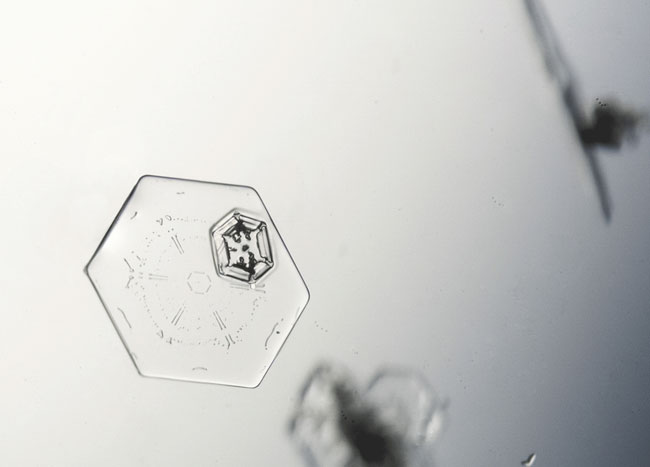

Snowflake photographed by Michael Peres during a January 19, 2019, snowstorm. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Plate-shaped snow crystal photographed by Michael Peres during a January 19, 2019, snowstorm. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Dendritic-shaped snow crystal photographed by Michael Peres during a January 19, 2019, snowstorm. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Snowflakes come in a variety of different shapes. What are some of your favorite shapes to photograph?

During the course of any winter, a wide variety of crystal types fall. My methods and equipment are focused towards photographing crystals that are 1 to 2 millimeters in size and are dendritic [“tree-like”]. All snowflakes start out as water molecules that form hexagons in the right conditions. These embryonic crystals are called stellar plates. They can be infinitely small, but they grow and add water molecules over time. At some time during their formation, they grow wings and other intricate structures. When this happens they become dendritic flakes. They are my favorite crystals to photograph. It has been my experience that I have the best luck when the air temperatures are between 15 and 25 degrees Fahrenheit [about -10 to -5 degrees Celsius].. During the course of a winter, each storm can bring a wide range of crystal types including columns, capped columns, needles, and granular snow to share a few types of crystals that can fall.

Technique used to select a snowflake to photograph. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

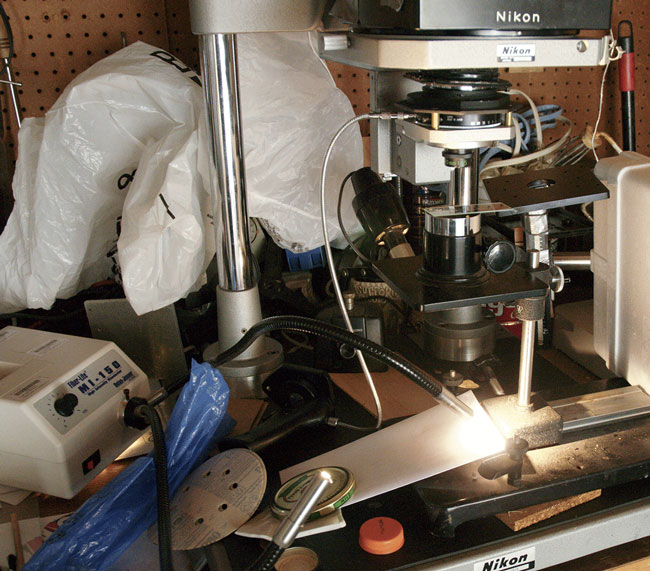

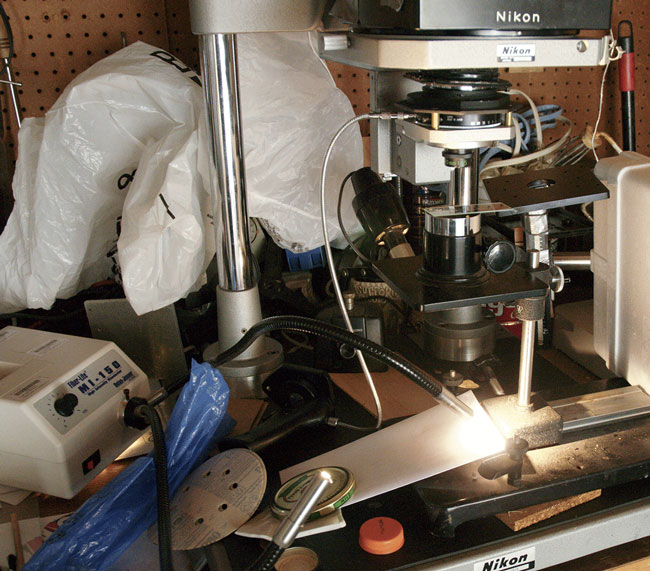

The microscope used by Professor Peres to photograph snowflakes. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Can you describe the general process you use to take a photograph of a snowflake?

My process starts by frequently watching the weather forecasts. My equipment is kept outside in the garage. Photographing ice crystals requires that everything I use be kept below 32 degrees Fahrenheit [0 Celsius]. I keep an inventory of glass slides with my microscope, and I use a fiber optic light source. Being a snowflake photographer is much like being a fireman and ready at a moment’s notice when things happen. These events can be at night, in the day, when I am at work, and when I am indisposed or when I am ready. When good crystals fall and I am available, I start my photographing.

I catch crystals that are falling using a baking tray with a piece of black velvet draped over the tray. Velvet is useful for isolating the best crystals but also allows for easy retrieval using a small needle taped to a pencil. Depending on the humidity and air temperatures, there is a natural static electricity in the needle and crystal. It allows me to lift the crystal using the needle because they are attracted to one another giving me a chance to position the crystal onto a clear glass slide. It is possible to photograph the crystals in the tray on the fabric but I prefer the isolation against a lighter background and have the opportunity to light from underneath.

I use a low power simple microscope. Basically, the microscope is a repurposed industrial macro stand. I use a 16- or 25-millimeter macro lens and the camera has a bellows. Attached to the bellows (extension tubes can also be used) is a DSLR camera body without a lens.

Once an interesting crystal has been identified in my catch tray, I move it to a glass slide using the needle on the pencil. The slide is placed onto the microscope’s focusing stage where I can compose and focus the image in the viewfinder of the camera.

I use a fiber optic illuminator with a bifurcated gooseneck light guide that illuminates the crystals. I shine light onto a variety of materials located below the stage to provide contrast and color to the light that is refracted into the crystal used to reveal the crystal’s facets.

Snowflake photograph from Michael Peres’s RIT snowflake gallery. Image via Michael Peres, RIT.

Any tips for those of us who have been trying to capture a good snowflake photograph with a macro lens? I for one am wondering if some temperatures are better than others for taking snowflake photos, and how on Earth do I keep my hands warm?

It is possible to photograph snowflakes with a smartphone or DSLR. The features and advantages of each camera are pretty clear. The smartphone has a pretty good sensor but focusing the lens, exposure management, and ability to magnify sometimes 1-millimeter crystals are real obstacles. There are accessory lenses that can be added to the smartphone. Photojojo is an excellent vendor of such lenses.

DSLR cameras are significantly better choices for this work and are equipped with a macro lens capable of at least 1:1. Canon sells a 65-millimeter macro lens that can achieve 5:1 magnification. Adding extension tubes or by using a simple bellows, you can increase the image size that the camera system produces. My typical crystals benefit from a 3 to 6x magnification.

I dress warmly for this work wearing many layers including insulated boots. I use gloves with finger holes but because of the delicate nature of focusing a microscope, moving the crystal in small increments, I benefit from more control and feel having nothing on my hands. Because of the adrenaline, I can typically work for up to 30 minutes before my hands cannot tolerate the conditions any longer.

I photograph using a medium aperture such as ƒ/5.6. Diffraction at these image sizes can cause the crystals to become less defined if I use a smaller aperture. Often I photograph wide open and create increased DOF images.

Snowflake photograph from Michael Peres’s RIT snowflake gallery. Image via Michael Peres, RIT.

Many thanks to Professor Peres for discussing his snowflake photography with EarthSky. More examples of his work can be viewed on his Instagram account @michael_peres and on his website at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT).

Want more? You can read about the attempts one of EarthSky’s intrepid contributors to photograph snowflakes in the archive here.

See some recent favorite snowflake photos from the EarthSky Community

If this post inspires you to give snowflake photography a shot, please submit your photos to EarthSky Community Photos! We love seeing and sharing your recent captures of the natural world!

Bottom line: How to take photos of snowflakes with Professor Michael Peres of the Rochester Institute of Technology.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2B9Uhku

Michael Peres uses a black velvet catch tray to capture falling snowflakes. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Michael Peres is a professor of biomedical photographic communications at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. He’s also an award-winning photo-educator, author, and science photographer, with work featured by CNN, Time, the Weather Channel, Nikon, and Mashable. EarthSky spoke with him via email in January, 2019, to learn more about his amazing photographs.

How did you get interested in photographing snowflakes?

In the winter of 2003–2004, one of my students visited an exhibition of Wilson Snowflake Bentley photographs on display at the Buffalo Museum and Science Center. Her excitement about trying to photograph snowflakes was contagious and within a short period of time on a wintry day in January, my microscopy class moved our gear outside and we tried. Little did I know how infectious the experience would be for me personally. Now, more than 15 years later, I am obsessed with the challenge during the long and snowy Rochester, New York, winters. Rochester on average can receive more than 105 inches of snow per season. One could speculate that amount of snow would provide ample subjects and chances to photograph unique and interesting ice crystals.

Snowflake photographed by Michael Peres during a January 19, 2019, snowstorm. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Plate-shaped snow crystal photographed by Michael Peres during a January 19, 2019, snowstorm. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Dendritic-shaped snow crystal photographed by Michael Peres during a January 19, 2019, snowstorm. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Snowflakes come in a variety of different shapes. What are some of your favorite shapes to photograph?

During the course of any winter, a wide variety of crystal types fall. My methods and equipment are focused towards photographing crystals that are 1 to 2 millimeters in size and are dendritic [“tree-like”]. All snowflakes start out as water molecules that form hexagons in the right conditions. These embryonic crystals are called stellar plates. They can be infinitely small, but they grow and add water molecules over time. At some time during their formation, they grow wings and other intricate structures. When this happens they become dendritic flakes. They are my favorite crystals to photograph. It has been my experience that I have the best luck when the air temperatures are between 15 and 25 degrees Fahrenheit [about -10 to -5 degrees Celsius].. During the course of a winter, each storm can bring a wide range of crystal types including columns, capped columns, needles, and granular snow to share a few types of crystals that can fall.

Technique used to select a snowflake to photograph. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

The microscope used by Professor Peres to photograph snowflakes. Photo appears courtesy of Michael Peres.

Can you describe the general process you use to take a photograph of a snowflake?

My process starts by frequently watching the weather forecasts. My equipment is kept outside in the garage. Photographing ice crystals requires that everything I use be kept below 32 degrees Fahrenheit [0 Celsius]. I keep an inventory of glass slides with my microscope, and I use a fiber optic light source. Being a snowflake photographer is much like being a fireman and ready at a moment’s notice when things happen. These events can be at night, in the day, when I am at work, and when I am indisposed or when I am ready. When good crystals fall and I am available, I start my photographing.

I catch crystals that are falling using a baking tray with a piece of black velvet draped over the tray. Velvet is useful for isolating the best crystals but also allows for easy retrieval using a small needle taped to a pencil. Depending on the humidity and air temperatures, there is a natural static electricity in the needle and crystal. It allows me to lift the crystal using the needle because they are attracted to one another giving me a chance to position the crystal onto a clear glass slide. It is possible to photograph the crystals in the tray on the fabric but I prefer the isolation against a lighter background and have the opportunity to light from underneath.

I use a low power simple microscope. Basically, the microscope is a repurposed industrial macro stand. I use a 16- or 25-millimeter macro lens and the camera has a bellows. Attached to the bellows (extension tubes can also be used) is a DSLR camera body without a lens.

Once an interesting crystal has been identified in my catch tray, I move it to a glass slide using the needle on the pencil. The slide is placed onto the microscope’s focusing stage where I can compose and focus the image in the viewfinder of the camera.

I use a fiber optic illuminator with a bifurcated gooseneck light guide that illuminates the crystals. I shine light onto a variety of materials located below the stage to provide contrast and color to the light that is refracted into the crystal used to reveal the crystal’s facets.

Snowflake photograph from Michael Peres’s RIT snowflake gallery. Image via Michael Peres, RIT.

Any tips for those of us who have been trying to capture a good snowflake photograph with a macro lens? I for one am wondering if some temperatures are better than others for taking snowflake photos, and how on Earth do I keep my hands warm?

It is possible to photograph snowflakes with a smartphone or DSLR. The features and advantages of each camera are pretty clear. The smartphone has a pretty good sensor but focusing the lens, exposure management, and ability to magnify sometimes 1-millimeter crystals are real obstacles. There are accessory lenses that can be added to the smartphone. Photojojo is an excellent vendor of such lenses.

DSLR cameras are significantly better choices for this work and are equipped with a macro lens capable of at least 1:1. Canon sells a 65-millimeter macro lens that can achieve 5:1 magnification. Adding extension tubes or by using a simple bellows, you can increase the image size that the camera system produces. My typical crystals benefit from a 3 to 6x magnification.

I dress warmly for this work wearing many layers including insulated boots. I use gloves with finger holes but because of the delicate nature of focusing a microscope, moving the crystal in small increments, I benefit from more control and feel having nothing on my hands. Because of the adrenaline, I can typically work for up to 30 minutes before my hands cannot tolerate the conditions any longer.

I photograph using a medium aperture such as ƒ/5.6. Diffraction at these image sizes can cause the crystals to become less defined if I use a smaller aperture. Often I photograph wide open and create increased DOF images.

Snowflake photograph from Michael Peres’s RIT snowflake gallery. Image via Michael Peres, RIT.

Many thanks to Professor Peres for discussing his snowflake photography with EarthSky. More examples of his work can be viewed on his Instagram account @michael_peres and on his website at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT).

Want more? You can read about the attempts one of EarthSky’s intrepid contributors to photograph snowflakes in the archive here.

See some recent favorite snowflake photos from the EarthSky Community

If this post inspires you to give snowflake photography a shot, please submit your photos to EarthSky Community Photos! We love seeing and sharing your recent captures of the natural world!

Bottom line: How to take photos of snowflakes with Professor Michael Peres of the Rochester Institute of Technology.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2B9Uhku

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire