November 20, 1889. Happy birthday, Edwin Hubble! The Hubble Space Telescope is named for this astronomer, because Hubble’s work helped define our modern cosmology, our idea of the universe as a whole.

The 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

Hubble helped astronomers see that we live in an expanding universe, one in which every galaxy is moving away from every other. If you read an introductory book about galaxies, or take an introductory class on them, you’ll likely encounter what’s known as Hubble’s law. In its simplest form, it states that, the more distant the galaxy, the faster it is moving away from us. This concept lies at the heart of our modern cosmology, in which the entire universe – space, time and matter – is thought to have been born in a Big Bang.

In 2018, the International Astronomical Union, or IAU, voted to rename Hubble’s law as the Hubble-Lemaître law. More about that change below.

So what did Edwin Hubble do to deserve such a special place in the history of astronomy?

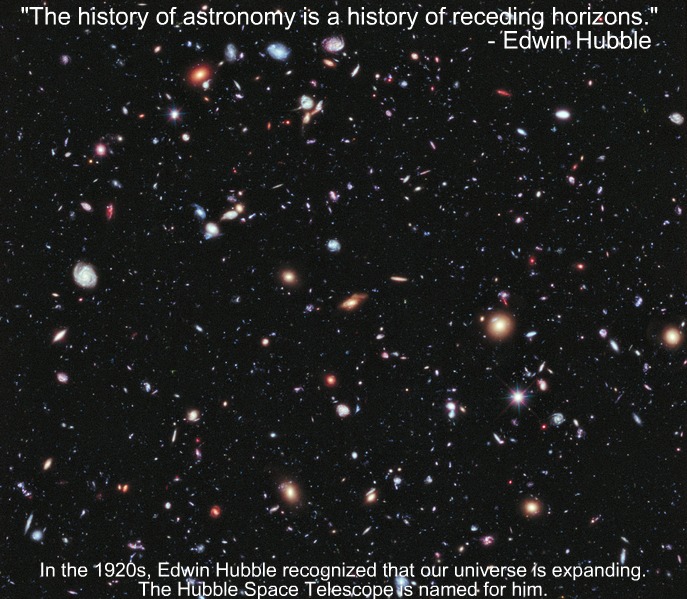

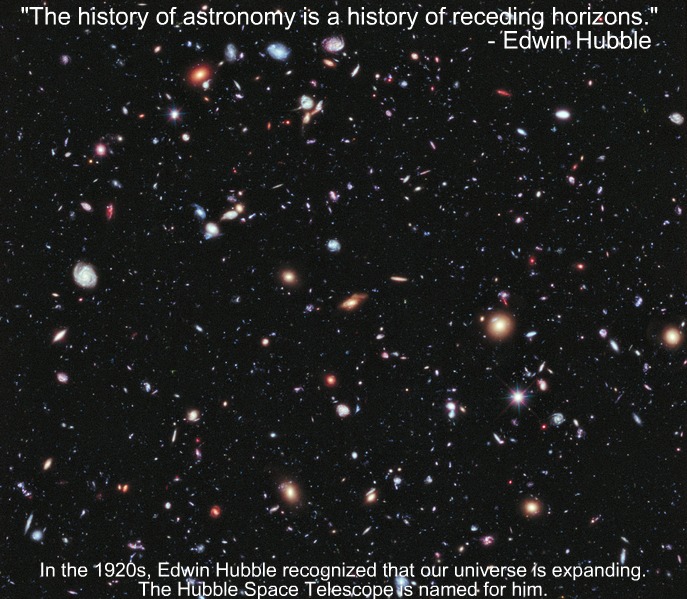

This image is the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field, released in 2012. Nearly every speck of light here is a separate galaxy, beyond our Milky Way. Read more about this image here.

Consider that most astronomers 100 years ago believed that our whole universe consisted of just one galaxy, our own Milky Way. In the 1920s, Hubble was among the first to recognize that there is a universe of galaxies located beyond the boundaries of our Milky Way.

During the 1920s, Edwin Hubble observed stars that vary in brightness in a patch of light known at the time as the Andromeda nebula. He knew that these stars changed in brightness in a way that depended on their true brightness. He then saw how bright they looked to find the distance to the Andromeda nebula.

At the time, many astronomers believed that the Andromeda nebula was a forming solar system, located within the Milky Way’s boundaries. Hubble showed that this patch of light was really a separate galaxy – what we know today as the Andromeda galaxy – the nearest large spiral galaxy beyond our Milky Way.

Today, we know that this nearest large spiral galaxy, the Andromeda galaxy – is 2.2 million light-years beyond our Milky Way. We also know that other galaxies extend around us in space for many billions of light-years. But to people in the 1920s, it was a revelation! As soon as the spiral nebulae – like the Andromeda galaxy – were revealed as separate galaxies, the known universe got much bigger!

The Andromeda galaxy and two satellite galaxies as seen through a powerful telescope. In Hubble’s time, astronomers believed this object resided within our own Milky Way galaxy. Hubble used a class of variable stars called Cepheid variables to show that the Andromeda galaxy is an island of stars in space, external to our Milky Way. Image via NOAO.

But was this huge universe stationary? Or was it expanding, or contracting?

The answer involved the light of galaxies as a whole. Astronomers observed that the light of distant galaxies was shifted toward the red end of the light spectrum. This red shift was interpreted as a sign that the galaxies are moving away from us. Hubble and his colleagues compared the distance estimates to galaxies with their red shifts. And – on March 15, 1929 – Hubble published his observation that the farthest galaxies are moving away faster than the closest ones.

This is the insight that became known as Hubble’s law.

It’s said that Albert Einstein was elated to hear of Hubble’s work. Einstein’s Theory of Relativity implied that the universe must either be expanding or contracting. But Einstein himself rejected this notion in favor of the accepted idea that the universe was stationary and had always existed. When Hubble presented his evidence of the expansion of the universe, Einstein embraced the idea. He called his adherence to the old idea “my greatest blunder.”

Hubble was a multi-talented man. Although he majored in science as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, a promise to his dying father caused him to take up a study of the law. He was also an amateur heavyweight boxer, and reportedly turned down the chance to fight professionally. He returned to science as a graduate student at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. In 1919, he accepted a position at the prestigious Mount Wilson Observatory in California, where he remained until his death in 1953. Shortly before his death, Hubble became the first astronomer to use the newly completed, famous, then-giant 200-inch (5.1-meter) reflector Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego, California.

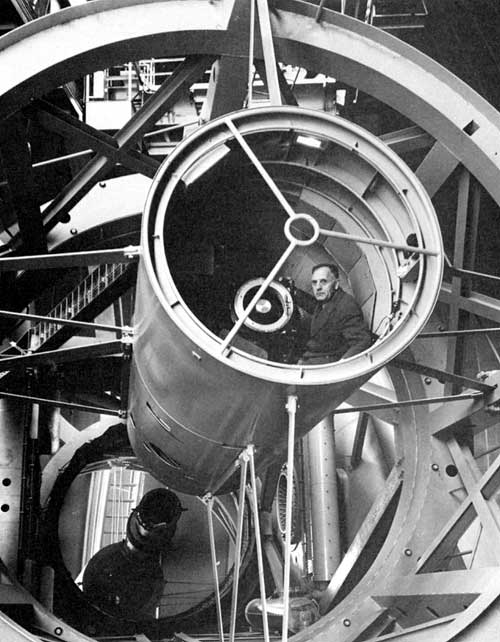

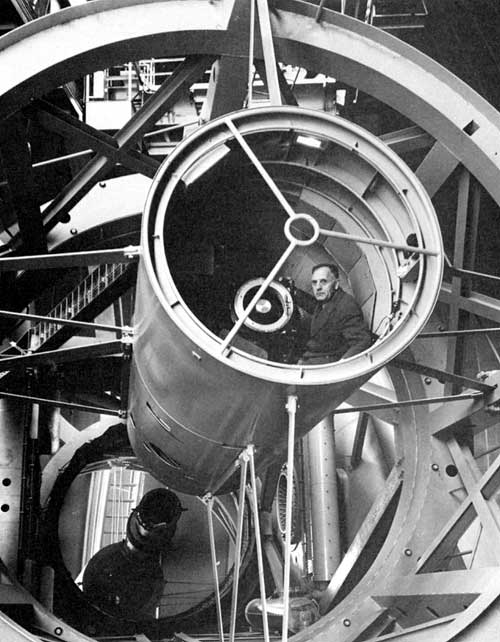

Edwin Hubble in the observer’s cage at the top of the tube of the 200-inch telescope on Palomar Mountain. The telescope was considered a marvel of technology when it was dedicated in 1948, much as the Hubble Space Telescope – named for Edwin Hubble – is today. Image courtesy Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories/AIP.

Renaming Hubble’s law as the Hubble-Lemaître law. In late October 2018, members of the International Astronomical Union – best-known among non-astronomers for demoting Pluto from major planet status in 2006 – voted to change the name of the Hubble law to honor the Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître.

Henceforth, the IAU recommended, the Hubble law would be known as the Hubble-Lemaître law. Of the 4,060 astronomers who cast votes (out of around 11,072 eligible members), 78 percent were in favor of this change.

In fact, in the 1920s, Georges Lemaître did describe, in the French language, how the expansion of the universe would cause galaxies to move away from Earth at speeds proportional to their distance. He described the relationship between a galaxy’s recessional speed and its distance some two years before Edwin Hubble did.

Among professional astronomers and students of the history of science, Lemaître’s name has long been known and honored for his achievement. Now the IAU has voted an acknowledgement of Lemaître’s contribution. Writing in Nature on October 30, 2018, Elizabeth Gibney said:

The move seems to be the first time an organization has voted to alter the name of a scientific law – although some scientists doubt whether the change will be noticed. The IAU has been the arbiter of planet and moon names since 1919, and oversees astronomers’ official catalogue of star names, but it has no formal mandate over the names of scientific laws.

Piero Benvenuti is a former IAU general secretary who proposed the name change. He told Nature that the new terminology is a recommendation only, saying:

If people will continue to use the Hubble law naming, nobody will object.

It remains to be seen if astronomers and their students will slowly shift into using the name Hubble-Lemaître law, instead of Hubble law. Checking a Google search engine today (November 2018), we are finding 119,000 results for this new name.

We’ll see what has happened in a year or two, when we check again!

Read more from Nature: Belgian priest recognized in Hubble-law name change

Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître published a paper on the expansion of the universe in 1927. Image via Emilio Segre Visual Archives/AIP/SPL/Nature.

Bottom line: Edwin Hubble’s birthday is November 20, 1889. Hubble showed there are separate galaxies beyond our Milky Way and that the more distant the galaxy, the faster it moves away from us. The Hubble Space Telescope is named for him.

Deepest view we have yet, into our universe: the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2QZiDDp

November 20, 1889. Happy birthday, Edwin Hubble! The Hubble Space Telescope is named for this astronomer, because Hubble’s work helped define our modern cosmology, our idea of the universe as a whole.

The 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

Hubble helped astronomers see that we live in an expanding universe, one in which every galaxy is moving away from every other. If you read an introductory book about galaxies, or take an introductory class on them, you’ll likely encounter what’s known as Hubble’s law. In its simplest form, it states that, the more distant the galaxy, the faster it is moving away from us. This concept lies at the heart of our modern cosmology, in which the entire universe – space, time and matter – is thought to have been born in a Big Bang.

In 2018, the International Astronomical Union, or IAU, voted to rename Hubble’s law as the Hubble-Lemaître law. More about that change below.

So what did Edwin Hubble do to deserve such a special place in the history of astronomy?

This image is the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field, released in 2012. Nearly every speck of light here is a separate galaxy, beyond our Milky Way. Read more about this image here.

Consider that most astronomers 100 years ago believed that our whole universe consisted of just one galaxy, our own Milky Way. In the 1920s, Hubble was among the first to recognize that there is a universe of galaxies located beyond the boundaries of our Milky Way.

During the 1920s, Edwin Hubble observed stars that vary in brightness in a patch of light known at the time as the Andromeda nebula. He knew that these stars changed in brightness in a way that depended on their true brightness. He then saw how bright they looked to find the distance to the Andromeda nebula.

At the time, many astronomers believed that the Andromeda nebula was a forming solar system, located within the Milky Way’s boundaries. Hubble showed that this patch of light was really a separate galaxy – what we know today as the Andromeda galaxy – the nearest large spiral galaxy beyond our Milky Way.

Today, we know that this nearest large spiral galaxy, the Andromeda galaxy – is 2.2 million light-years beyond our Milky Way. We also know that other galaxies extend around us in space for many billions of light-years. But to people in the 1920s, it was a revelation! As soon as the spiral nebulae – like the Andromeda galaxy – were revealed as separate galaxies, the known universe got much bigger!

The Andromeda galaxy and two satellite galaxies as seen through a powerful telescope. In Hubble’s time, astronomers believed this object resided within our own Milky Way galaxy. Hubble used a class of variable stars called Cepheid variables to show that the Andromeda galaxy is an island of stars in space, external to our Milky Way. Image via NOAO.

But was this huge universe stationary? Or was it expanding, or contracting?

The answer involved the light of galaxies as a whole. Astronomers observed that the light of distant galaxies was shifted toward the red end of the light spectrum. This red shift was interpreted as a sign that the galaxies are moving away from us. Hubble and his colleagues compared the distance estimates to galaxies with their red shifts. And – on March 15, 1929 – Hubble published his observation that the farthest galaxies are moving away faster than the closest ones.

This is the insight that became known as Hubble’s law.

It’s said that Albert Einstein was elated to hear of Hubble’s work. Einstein’s Theory of Relativity implied that the universe must either be expanding or contracting. But Einstein himself rejected this notion in favor of the accepted idea that the universe was stationary and had always existed. When Hubble presented his evidence of the expansion of the universe, Einstein embraced the idea. He called his adherence to the old idea “my greatest blunder.”

Hubble was a multi-talented man. Although he majored in science as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, a promise to his dying father caused him to take up a study of the law. He was also an amateur heavyweight boxer, and reportedly turned down the chance to fight professionally. He returned to science as a graduate student at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. In 1919, he accepted a position at the prestigious Mount Wilson Observatory in California, where he remained until his death in 1953. Shortly before his death, Hubble became the first astronomer to use the newly completed, famous, then-giant 200-inch (5.1-meter) reflector Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego, California.

Edwin Hubble in the observer’s cage at the top of the tube of the 200-inch telescope on Palomar Mountain. The telescope was considered a marvel of technology when it was dedicated in 1948, much as the Hubble Space Telescope – named for Edwin Hubble – is today. Image courtesy Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories/AIP.

Renaming Hubble’s law as the Hubble-Lemaître law. In late October 2018, members of the International Astronomical Union – best-known among non-astronomers for demoting Pluto from major planet status in 2006 – voted to change the name of the Hubble law to honor the Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître.

Henceforth, the IAU recommended, the Hubble law would be known as the Hubble-Lemaître law. Of the 4,060 astronomers who cast votes (out of around 11,072 eligible members), 78 percent were in favor of this change.

In fact, in the 1920s, Georges Lemaître did describe, in the French language, how the expansion of the universe would cause galaxies to move away from Earth at speeds proportional to their distance. He described the relationship between a galaxy’s recessional speed and its distance some two years before Edwin Hubble did.

Among professional astronomers and students of the history of science, Lemaître’s name has long been known and honored for his achievement. Now the IAU has voted an acknowledgement of Lemaître’s contribution. Writing in Nature on October 30, 2018, Elizabeth Gibney said:

The move seems to be the first time an organization has voted to alter the name of a scientific law – although some scientists doubt whether the change will be noticed. The IAU has been the arbiter of planet and moon names since 1919, and oversees astronomers’ official catalogue of star names, but it has no formal mandate over the names of scientific laws.

Piero Benvenuti is a former IAU general secretary who proposed the name change. He told Nature that the new terminology is a recommendation only, saying:

If people will continue to use the Hubble law naming, nobody will object.

It remains to be seen if astronomers and their students will slowly shift into using the name Hubble-Lemaître law, instead of Hubble law. Checking a Google search engine today (November 2018), we are finding 119,000 results for this new name.

We’ll see what has happened in a year or two, when we check again!

Read more from Nature: Belgian priest recognized in Hubble-law name change

Belgian priest and astronomer Georges Lemaître published a paper on the expansion of the universe in 1927. Image via Emilio Segre Visual Archives/AIP/SPL/Nature.

Bottom line: Edwin Hubble’s birthday is November 20, 1889. Hubble showed there are separate galaxies beyond our Milky Way and that the more distant the galaxy, the faster it moves away from us. The Hubble Space Telescope is named for him.

Deepest view we have yet, into our universe: the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2QZiDDp

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire