Mars as seen by one of the Viking orbiters in the late 1970s. We now know there are organics there, but where did they come from? Image via NASA.

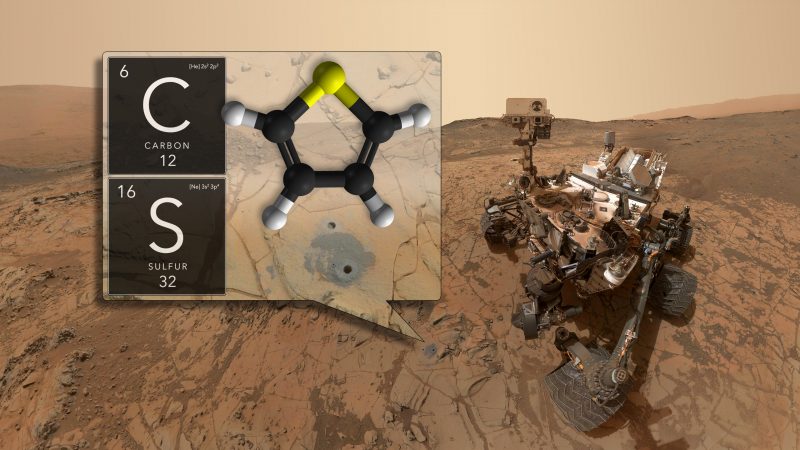

For a long time, it wasn’t known if organic compounds – compounds containing carbon – existed on Mars. They are ubiquitous within living things on Earth, but – due to its thinner atmosphere – these compounds would be destroyed on Mars’ surface by strong incoming ultraviolet radiation. Still, scientists have thought that there should be some organics on Mars – hidden within rocks or perhaps just under the surface – even if just very simple ones from the meteorites that strike Mars regularly. Various landers and rovers found hints of organics, but nothing too substantial. Then, earlier in 2018, the Curiosity rover finally hit pay dirt, finding evidence for abundant organics in the ancient mudstone rocks in Gale crater, which used to be a martian lake billions of years ago. These carbon molecules ranged from simple to fairly complex, but their actual origin was still unknown. They could be created by abiotic processes (without life). Or they could be the molecular remains of once-living organisms.

Now, a new study by scientists at the Carnegie Institute for Science has shown one possible way that these or similar organics might have been created on Mars. The new peer-reviewed paper – by Andrew Steele and his colleagues – has been published in Science Advances.

The researchers studied organics found in three martian meteorites – Tissint, Nakhla, and NWA 1950 – and compared them to the organics discovered by Curiosity. They found that both sets of organic carbon were quite similar, suggesting a possible similar origin. From the paper:

Here, we show that martian meteorites Tissint, Nakhla, and NWA 1950 have an inventory of organic carbon species associated with fluid-mineral reactions that are remarkably consistent with those detected by the Mars Science Laboratory mission [with its Curiosity rover].

Earlier this year, NASA’s Curiosity rover found organic carbon compounds in ancient mudstones, similar to ones previously discovered in martian meteorites. Image via NASA/GSFC.

Previously, in 2012, Steele led another team that determined the organics found in 10 different martian meteorites was indigenous to Mars, not contamination from Earth, but also was not biological in origin. But if those carbon deposits were not biological, then how did they form? According to Steele:

Revealing the processes by which organic carbon compounds form on Mars has been a matter of tremendous interest for understanding its potential for habitability.

Basically, according to the paper, Mars’ organics may have originated from a series of electrochemical reactions between briny liquids and volcanic minerals, in other words, natural “batteries.”

So what about the organics found by Curiosity? Steele and his team looked closer at the organics in the meteorites – using advanced microscopy and spectroscopy – and found that they were likely created by electrochemical corrosion of minerals in martian rocks by a surrounding salty liquid brine. As Steele noted:

The discovery that natural systems can essentially form a small corrosion-powered battery that drives electrochemical reactions between minerals and surrounding liquid has major implications for the astrobiology field.

The Tissint martian meteorite, one of several that were found to contain organic material. Image via Alain Herzog/EPFL.

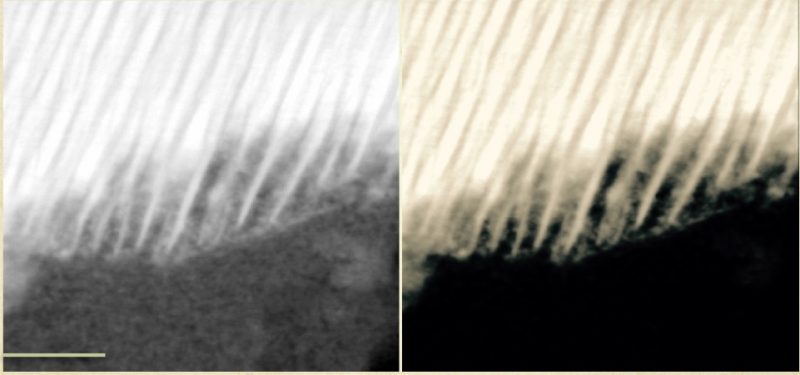

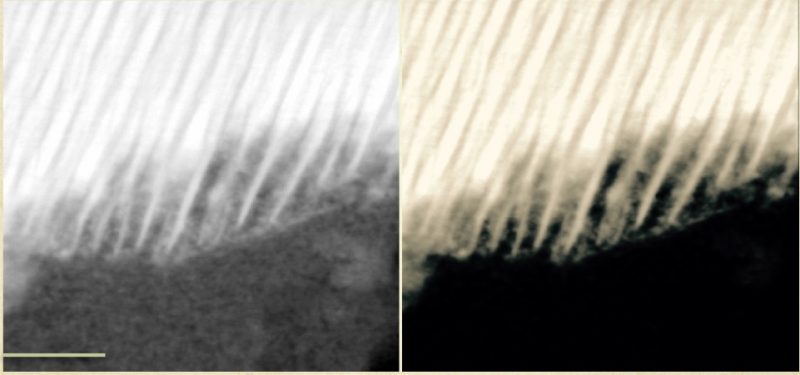

A high-resolution transmission electron micrograph (scale 50nm), from a transmission electron microscope, of a grain from the martian meteorite Nakhla. The organic carbon layers are found between the intact “tines.” This texture is created when the volcanic minerals of the Martian rock interact with a salty brine and become the anode and cathode of a naturally occurring battery in a corrosion reaction. This reaction would then have enough energy – under certain conditions – to synthesize organic carbon. Image via Andrew Steele/Science Advances.

Does this prove the Curiosity organics were created in the same way? No, but it is a viable answer. Curiosity itself is somewhat limited in being able to determine whether any organics are biological in origin or not. The upcoming 2020 rover will be able to do that, NASA has said.

The team further postulates that similar processes could also occur on Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Enceladus and other bodies in our solar system – anywhere that igneous rocks are surrounded by salty brines. This could also have a bearing on their potential habitability as well.

Bottom line: The origin of organics on Mars is still unknown, but this new study from the Carnegie Institute for Science may hold some important clues for how at least some of them were created.

Source: Organic synthesis on Mars by electrochemical reduction of CO2

Via Carnegie Institution for Science

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2zHec8O

Mars as seen by one of the Viking orbiters in the late 1970s. We now know there are organics there, but where did they come from? Image via NASA.

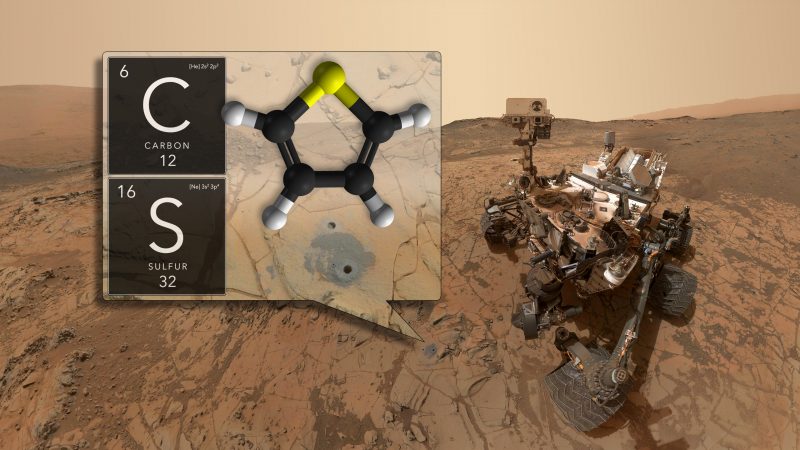

For a long time, it wasn’t known if organic compounds – compounds containing carbon – existed on Mars. They are ubiquitous within living things on Earth, but – due to its thinner atmosphere – these compounds would be destroyed on Mars’ surface by strong incoming ultraviolet radiation. Still, scientists have thought that there should be some organics on Mars – hidden within rocks or perhaps just under the surface – even if just very simple ones from the meteorites that strike Mars regularly. Various landers and rovers found hints of organics, but nothing too substantial. Then, earlier in 2018, the Curiosity rover finally hit pay dirt, finding evidence for abundant organics in the ancient mudstone rocks in Gale crater, which used to be a martian lake billions of years ago. These carbon molecules ranged from simple to fairly complex, but their actual origin was still unknown. They could be created by abiotic processes (without life). Or they could be the molecular remains of once-living organisms.

Now, a new study by scientists at the Carnegie Institute for Science has shown one possible way that these or similar organics might have been created on Mars. The new peer-reviewed paper – by Andrew Steele and his colleagues – has been published in Science Advances.

The researchers studied organics found in three martian meteorites – Tissint, Nakhla, and NWA 1950 – and compared them to the organics discovered by Curiosity. They found that both sets of organic carbon were quite similar, suggesting a possible similar origin. From the paper:

Here, we show that martian meteorites Tissint, Nakhla, and NWA 1950 have an inventory of organic carbon species associated with fluid-mineral reactions that are remarkably consistent with those detected by the Mars Science Laboratory mission [with its Curiosity rover].

Earlier this year, NASA’s Curiosity rover found organic carbon compounds in ancient mudstones, similar to ones previously discovered in martian meteorites. Image via NASA/GSFC.

Previously, in 2012, Steele led another team that determined the organics found in 10 different martian meteorites was indigenous to Mars, not contamination from Earth, but also was not biological in origin. But if those carbon deposits were not biological, then how did they form? According to Steele:

Revealing the processes by which organic carbon compounds form on Mars has been a matter of tremendous interest for understanding its potential for habitability.

Basically, according to the paper, Mars’ organics may have originated from a series of electrochemical reactions between briny liquids and volcanic minerals, in other words, natural “batteries.”

So what about the organics found by Curiosity? Steele and his team looked closer at the organics in the meteorites – using advanced microscopy and spectroscopy – and found that they were likely created by electrochemical corrosion of minerals in martian rocks by a surrounding salty liquid brine. As Steele noted:

The discovery that natural systems can essentially form a small corrosion-powered battery that drives electrochemical reactions between minerals and surrounding liquid has major implications for the astrobiology field.

The Tissint martian meteorite, one of several that were found to contain organic material. Image via Alain Herzog/EPFL.

A high-resolution transmission electron micrograph (scale 50nm), from a transmission electron microscope, of a grain from the martian meteorite Nakhla. The organic carbon layers are found between the intact “tines.” This texture is created when the volcanic minerals of the Martian rock interact with a salty brine and become the anode and cathode of a naturally occurring battery in a corrosion reaction. This reaction would then have enough energy – under certain conditions – to synthesize organic carbon. Image via Andrew Steele/Science Advances.

Does this prove the Curiosity organics were created in the same way? No, but it is a viable answer. Curiosity itself is somewhat limited in being able to determine whether any organics are biological in origin or not. The upcoming 2020 rover will be able to do that, NASA has said.

The team further postulates that similar processes could also occur on Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Enceladus and other bodies in our solar system – anywhere that igneous rocks are surrounded by salty brines. This could also have a bearing on their potential habitability as well.

Bottom line: The origin of organics on Mars is still unknown, but this new study from the Carnegie Institute for Science may hold some important clues for how at least some of them were created.

Source: Organic synthesis on Mars by electrochemical reduction of CO2

Via Carnegie Institution for Science

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2zHec8O

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire