We’ve known for decades that black holes exist, and that matter sometimes falls into them, and now we have the first published evidence – from a team of UK astronomers – of matter falling into a black hole at 30 percent of the speed of light. This is much faster than what’s been observed in the past, but it isn’t unexpected. Recent computer simulations suggest a mechanism – via misaligned disks around the hole – by which gas can fall directly in at high speed. The team used data from the European Space Agency’s X-ray observatory XMM-Newton to make the discovery. The black hole is a supermassive one, located at the heart of a galaxy known as PG1211+143, about a billion light-years away. Ken Pounds of the University of Leicester, who led the team that made the discovery, said:

We were able to follow an Earth-sized clump of matter for about a day, as it was pulled towards the black hole, accelerating to a third of the velocity of light before being swallowed up by the hole.

The velocity of light is 186,000 miles (300,000 km) per second.

Cool, yes? These results appeared in a paper published September 3, 2018 in the peer-reviewed journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

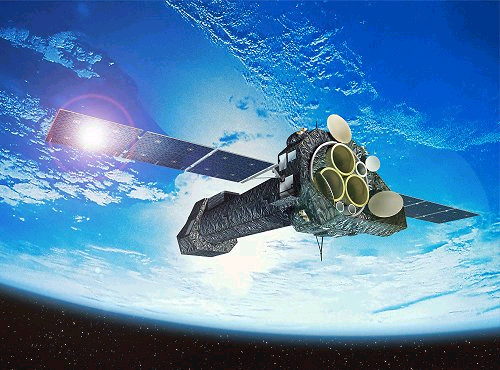

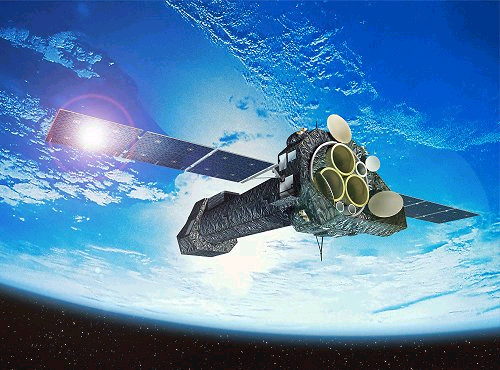

The XMM-Newton spacecraft, via ESA/ University of Leicester/RAS.

The researchers used XMM-Newton data to examine at X-ray spectra (where X-rays are dispersed by wavelength) of the galaxy PG211+143. This object was already known as one likely to have a supermassive black hole at its core (as most galaxies now are thought to do). The team’s statement explained:

The researchers found the spectra to be strongly red-shifted, showing the observed matter to be falling into the black hole at the enormous speed of 30 per cent of the speed of light, or around 100,000 kilometers per second [60,000 mps]. The gas has almost no rotation around the hole, and is detected extremely close to it in astronomical terms, at a distance of only 20 times the hole’s size (its event horizon, the boundary of the region where escape is no longer possible).

Most infall to black holes doesn’t move so fast, because, before it enters the hole, the material forms an accretion disk. The astronomers explained:

… black holes are so compact that gas is almost always rotating too much to fall in directly. Instead it orbits the hole, approaching gradually through an accretion disk – a sequence of circular orbits of decreasing size.

Why, then, did the material observed in galaxy PG211+143 fall directly into a black hole? The astronomers said the high velocity could have been the result of misaligned disks of material rotating around the black hole:

The orbit of the gas around the black hole is often assumed to be aligned with the rotation of the black hole, but there is no compelling reason for this to be the case …

Until now it has been unclear how misaligned rotation might affect the in-fall of gas. This is particularly relevant to the feeding of supermassive black holes since matter (interstellar gas clouds or even isolated stars) can fall in from any direction.

As it turns out, theorists at University of Leicester recently used the UK’s Dirac supercomputer facility to simulate the ‘tearing’ of misaligned accretion disks around compact objects. The astronomers explained:

This work has shown that rings of gas can break off and collide with each other, cancelling out their rotation and leaving gas to fall directly towards the black hole.

And now, as often happens, the theoretical work has been followed by an observation. Pounds commented:

The galaxy we were observing with XMM-Newton has a 40 million solar mass black hole which is very bright and evidently well fed. Indeed some 15 years ago we detected a powerful wind indicating the hole was being over-fed. While such winds are now found in many active galaxies, PG1211+143 has now yielded another ‘first’, with the detection of matter plunging directly into the hole itself.

Characteristic disk structure from the simulation of a misaligned disk around a spinning black hole. Image via K. Pounds et al./ University of Leicester/RAS.

Bottom line: Astronomers used data from ESA’s X-ray space observatory XMM-Newton to discover a supermassive black hole, in a galaxy about a billion light-years away, into which matter is falling at some one-third of light speed.

Source: An ultrafast inflow in the luminous Seyfert PG1211+143

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2xMoMeQ

We’ve known for decades that black holes exist, and that matter sometimes falls into them, and now we have the first published evidence – from a team of UK astronomers – of matter falling into a black hole at 30 percent of the speed of light. This is much faster than what’s been observed in the past, but it isn’t unexpected. Recent computer simulations suggest a mechanism – via misaligned disks around the hole – by which gas can fall directly in at high speed. The team used data from the European Space Agency’s X-ray observatory XMM-Newton to make the discovery. The black hole is a supermassive one, located at the heart of a galaxy known as PG1211+143, about a billion light-years away. Ken Pounds of the University of Leicester, who led the team that made the discovery, said:

We were able to follow an Earth-sized clump of matter for about a day, as it was pulled towards the black hole, accelerating to a third of the velocity of light before being swallowed up by the hole.

The velocity of light is 186,000 miles (300,000 km) per second.

Cool, yes? These results appeared in a paper published September 3, 2018 in the peer-reviewed journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The XMM-Newton spacecraft, via ESA/ University of Leicester/RAS.

The researchers used XMM-Newton data to examine at X-ray spectra (where X-rays are dispersed by wavelength) of the galaxy PG211+143. This object was already known as one likely to have a supermassive black hole at its core (as most galaxies now are thought to do). The team’s statement explained:

The researchers found the spectra to be strongly red-shifted, showing the observed matter to be falling into the black hole at the enormous speed of 30 per cent of the speed of light, or around 100,000 kilometers per second [60,000 mps]. The gas has almost no rotation around the hole, and is detected extremely close to it in astronomical terms, at a distance of only 20 times the hole’s size (its event horizon, the boundary of the region where escape is no longer possible).

Most infall to black holes doesn’t move so fast, because, before it enters the hole, the material forms an accretion disk. The astronomers explained:

… black holes are so compact that gas is almost always rotating too much to fall in directly. Instead it orbits the hole, approaching gradually through an accretion disk – a sequence of circular orbits of decreasing size.

Why, then, did the material observed in galaxy PG211+143 fall directly into a black hole? The astronomers said the high velocity could have been the result of misaligned disks of material rotating around the black hole:

The orbit of the gas around the black hole is often assumed to be aligned with the rotation of the black hole, but there is no compelling reason for this to be the case …

Until now it has been unclear how misaligned rotation might affect the in-fall of gas. This is particularly relevant to the feeding of supermassive black holes since matter (interstellar gas clouds or even isolated stars) can fall in from any direction.

As it turns out, theorists at University of Leicester recently used the UK’s Dirac supercomputer facility to simulate the ‘tearing’ of misaligned accretion disks around compact objects. The astronomers explained:

This work has shown that rings of gas can break off and collide with each other, cancelling out their rotation and leaving gas to fall directly towards the black hole.

And now, as often happens, the theoretical work has been followed by an observation. Pounds commented:

The galaxy we were observing with XMM-Newton has a 40 million solar mass black hole which is very bright and evidently well fed. Indeed some 15 years ago we detected a powerful wind indicating the hole was being over-fed. While such winds are now found in many active galaxies, PG1211+143 has now yielded another ‘first’, with the detection of matter plunging directly into the hole itself.

Characteristic disk structure from the simulation of a misaligned disk around a spinning black hole. Image via K. Pounds et al./ University of Leicester/RAS.

Bottom line: Astronomers used data from ESA’s X-ray space observatory XMM-Newton to discover a supermassive black hole, in a galaxy about a billion light-years away, into which matter is falling at some one-third of light speed.

Source: An ultrafast inflow in the luminous Seyfert PG1211+143

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2xMoMeQ

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire