Artist’s concept of some known habitable-zone super-Earth planets with similarities to Earth. Some or even all of them could have oceans. From left: Kepler-22b, Kepler-69c, Kepler-452b, Kepler-62f and Kepler-186f. Earth itself is at the right. Image via NASA.

When it comes to searching for evidence of alien life, the phrase follow the water is often quoted as a guiding principle. All life on Earth depends on water, so it makes sense to focus on other places where water exists as well. This has been true not only in our own solar system – notably Mars, Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus – but also for exoplanets orbiting other stars.

But how common is water on those distant worlds?

It is difficult to know the answer specifically since all exoplanets are so far away, outside our solar system, orbiting distant stars. But astronomers are now finding more clues thanks to advancements in telescope observing technologies. It turns out that water worlds are probably quite common. That’s according to a new study just presented at the Goldschmidt Conference in Boston on August 17, 2018. The study suggests that some super-Earth exoplanets are likely very rich in water – much more so than Earth.

More specifically, astronomers found that exoplanets which are between two and four times the size of Earth are likely to have water as a major component of their composition. These super-Earths, as they’re called, are worlds larger than Earth but smaller than ice giants like Uranus and Neptune. Most are thought to be rocky, with atmospheres, like Earth, and now it seems that many probably have oceans, as well.

NASA now has programs dedicated to the study of ocean worlds in the solar system and beyond. Image via NASA.

The new findings are based on data from the Kepler Space Telescope and the Gaia mission, which show that many of the already known planets of this type (out of nearly 4,000 exoplanets confirmed so far) could contain as much as 50 percent water. That upper limit is an enormous amount, compared to the water content of Earth, which is only 0.02 percent water (by weight). As lead researcher Dr. Li Zeng at Harvard University noted:

It was a huge surprise to realize that there must be so many waterworlds.

The results come from measuring the planets’ mass and radius. These observations allowed scientists to calculate the average densities of the planets, putting constraints on their bulk compositions and internal structures. The scientists found that they can be categorized into two general groups. According to Zeng:

We have looked at how mass relates to radius, and developed a model which might explain the relationship. The model indicates that those exoplanets which have a radius of around 1.5x Earth radius tend to be rocky planets (of typically 5x the mass of the Earth), while those with a radius of 2.5x Earth radius (with a mass around 10x that of the Earth) are probably water worlds.

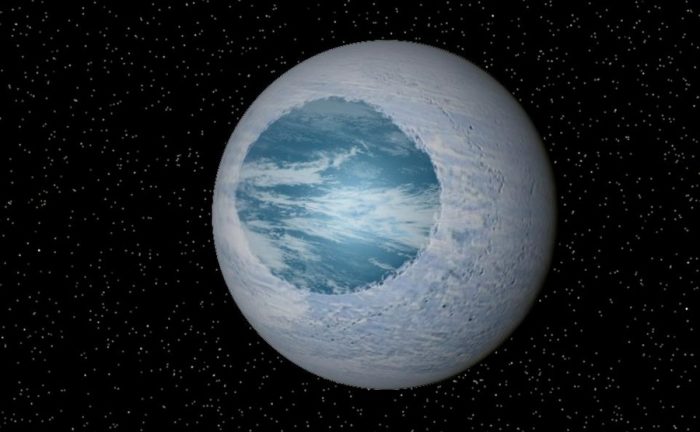

One type of possible water world is an “eyeball” planet, where the star-facing side is able to maintain a liquid-water ocean, while the rest of the surface is ice. Image via eburacum45/DeviantArt.

Those larger planets would be true water worlds, containing much more water than Earth. The entire surface of such planets could be covered by deep oceans, with no land masses or continents. Think of water moons like Europa or Enceladus, with global oceans, but without the ice layer on top. As Zeng explained:

This is water, but not as commonly found here on Earth. Their surface temperature is expected to be in the 200 to 500 degree Celsius range [400 to 900 Fahrenheit]. Their surface may be shrouded in a water-vapor-dominated atmosphere, with a liquid water layer underneath. Moving deeper, one would expect to find this water transforms into high-pressure ices before we reach the solid rocky core. The beauty of the model is that it explains just how composition relates to the known facts about these planets.

Our data indicate that about 35 percent of all known exoplanets which are bigger than Earth should be water-rich. These water worlds likely formed in similar ways to the giant planet cores (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) which we find in our own solar system. The newly-launched TESS mission will find many more of them, with the help of ground-based spectroscopic follow-up. The next generation space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), will hopefully characterize the atmosphere of some of them. This is an exciting time for those interested in these remote worlds.

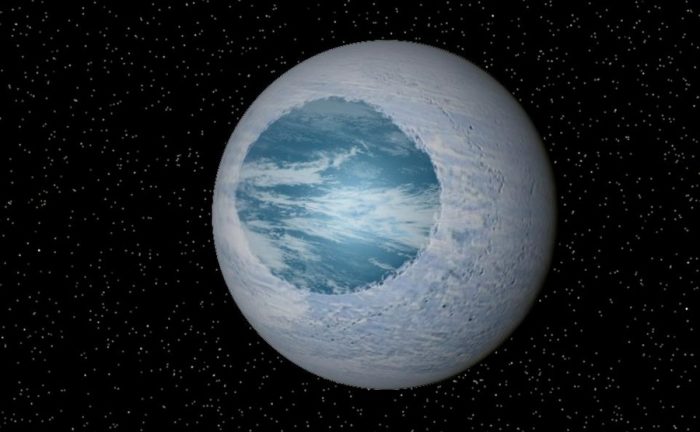

Kepler-22b is a super-Earth exoplanet which may be covered by a global ocean. Image via NASA.

Sara Seager, Professor of Planetary Science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and deputy science director of the recently-launched Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission, also gave her thoughts on this:

It’s amazing to think that the enigmatic intermediate-size exoplanets could be water worlds with vast amounts of water. Hopefully atmosphere observations in the future – of thick steam atmospheres – can support or refute the new findings.

As to how many of these water-worlds could support life, that is still an open question. Some alien oceans may lack the chemical nutrients or energy sources needed for evolution to gain a foothold. There are still a lot of unknowns at this point, but just the fact that these kinds of wet worlds seem to be common is an exciting finding. If life were to be discovered on one or more of the ocean moons in our own solar system, that would significantly increase the chances that life could arise on many different ocean worlds.

A global water ocean lies beneath the cracked icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa. Image via NASA/JPL.

Upcoming missions such as TESS and JWST will be able to further study these and other kinds of alien planetary environments, analyzing their atmospheres for signs of biomarkers produced by living organisms. Until then, we can mostly just speculate, but the findings so far are promising.

Bottom line: Astronomers think water worlds might be common in our galaxy – some of them larger and with much more water than Earth, including deep, global oceans. This will significantly impact the search for evidence of life elsewhere.

Source: Growth Model Interpretation of Planet Size Distribution

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2NboVhx

Artist’s concept of some known habitable-zone super-Earth planets with similarities to Earth. Some or even all of them could have oceans. From left: Kepler-22b, Kepler-69c, Kepler-452b, Kepler-62f and Kepler-186f. Earth itself is at the right. Image via NASA.

When it comes to searching for evidence of alien life, the phrase follow the water is often quoted as a guiding principle. All life on Earth depends on water, so it makes sense to focus on other places where water exists as well. This has been true not only in our own solar system – notably Mars, Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus – but also for exoplanets orbiting other stars.

But how common is water on those distant worlds?

It is difficult to know the answer specifically since all exoplanets are so far away, outside our solar system, orbiting distant stars. But astronomers are now finding more clues thanks to advancements in telescope observing technologies. It turns out that water worlds are probably quite common. That’s according to a new study just presented at the Goldschmidt Conference in Boston on August 17, 2018. The study suggests that some super-Earth exoplanets are likely very rich in water – much more so than Earth.

More specifically, astronomers found that exoplanets which are between two and four times the size of Earth are likely to have water as a major component of their composition. These super-Earths, as they’re called, are worlds larger than Earth but smaller than ice giants like Uranus and Neptune. Most are thought to be rocky, with atmospheres, like Earth, and now it seems that many probably have oceans, as well.

NASA now has programs dedicated to the study of ocean worlds in the solar system and beyond. Image via NASA.

The new findings are based on data from the Kepler Space Telescope and the Gaia mission, which show that many of the already known planets of this type (out of nearly 4,000 exoplanets confirmed so far) could contain as much as 50 percent water. That upper limit is an enormous amount, compared to the water content of Earth, which is only 0.02 percent water (by weight). As lead researcher Dr. Li Zeng at Harvard University noted:

It was a huge surprise to realize that there must be so many waterworlds.

The results come from measuring the planets’ mass and radius. These observations allowed scientists to calculate the average densities of the planets, putting constraints on their bulk compositions and internal structures. The scientists found that they can be categorized into two general groups. According to Zeng:

We have looked at how mass relates to radius, and developed a model which might explain the relationship. The model indicates that those exoplanets which have a radius of around 1.5x Earth radius tend to be rocky planets (of typically 5x the mass of the Earth), while those with a radius of 2.5x Earth radius (with a mass around 10x that of the Earth) are probably water worlds.

One type of possible water world is an “eyeball” planet, where the star-facing side is able to maintain a liquid-water ocean, while the rest of the surface is ice. Image via eburacum45/DeviantArt.

Those larger planets would be true water worlds, containing much more water than Earth. The entire surface of such planets could be covered by deep oceans, with no land masses or continents. Think of water moons like Europa or Enceladus, with global oceans, but without the ice layer on top. As Zeng explained:

This is water, but not as commonly found here on Earth. Their surface temperature is expected to be in the 200 to 500 degree Celsius range [400 to 900 Fahrenheit]. Their surface may be shrouded in a water-vapor-dominated atmosphere, with a liquid water layer underneath. Moving deeper, one would expect to find this water transforms into high-pressure ices before we reach the solid rocky core. The beauty of the model is that it explains just how composition relates to the known facts about these planets.

Our data indicate that about 35 percent of all known exoplanets which are bigger than Earth should be water-rich. These water worlds likely formed in similar ways to the giant planet cores (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) which we find in our own solar system. The newly-launched TESS mission will find many more of them, with the help of ground-based spectroscopic follow-up. The next generation space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), will hopefully characterize the atmosphere of some of them. This is an exciting time for those interested in these remote worlds.

Kepler-22b is a super-Earth exoplanet which may be covered by a global ocean. Image via NASA.

Sara Seager, Professor of Planetary Science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and deputy science director of the recently-launched Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission, also gave her thoughts on this:

It’s amazing to think that the enigmatic intermediate-size exoplanets could be water worlds with vast amounts of water. Hopefully atmosphere observations in the future – of thick steam atmospheres – can support or refute the new findings.

As to how many of these water-worlds could support life, that is still an open question. Some alien oceans may lack the chemical nutrients or energy sources needed for evolution to gain a foothold. There are still a lot of unknowns at this point, but just the fact that these kinds of wet worlds seem to be common is an exciting finding. If life were to be discovered on one or more of the ocean moons in our own solar system, that would significantly increase the chances that life could arise on many different ocean worlds.

A global water ocean lies beneath the cracked icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa. Image via NASA/JPL.

Upcoming missions such as TESS and JWST will be able to further study these and other kinds of alien planetary environments, analyzing their atmospheres for signs of biomarkers produced by living organisms. Until then, we can mostly just speculate, but the findings so far are promising.

Bottom line: Astronomers think water worlds might be common in our galaxy – some of them larger and with much more water than Earth, including deep, global oceans. This will significantly impact the search for evidence of life elsewhere.

Source: Growth Model Interpretation of Planet Size Distribution

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2NboVhx

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire