A Burmese python coiled in the grass in South Florida. Image via Bryan Falk, USGS.

Pythons are an invasive species in South Florida, originally brought there by humans. Since 2000, when wildlife experts realized that pythons have a sizable population in Florida, scientists have been trying to study these creatures, trying to understand how to control them. Scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reported on August 21, 2018, on a new genetic study showing that many of Florida’s pythons are closely related to one another. In fact, most of them are genetically related as first or second cousins. The study also found that at least a few of the snakes in the invasive South Florida population are not 100 percent Burmese pythons. Instead, the genetic evidence shows at least 13 snakes out of about 400 studied are a cross between two separate species: Burmese pythons, which mostly inhabit wetlands, and Indian pythons, which prefer higher ground.

Does this mean that an entirely new species – a super-snake, as many media outlets suggest – has emerged or is emerging in South Florida?

Margaret Hunter is lead author of the new study, published August 19 in the peer-reviewed journal Ecology and Evolution In a statement, she said the South Florida pythons:

… spring from a tangled family tree, with consequences for the species’ future spread that are hard to predict …

Sometimes interbreeding between related species can lead to hybrid vigor, that is, the best traits of two species are passed onto their offspring. Hybrid vigor can potentially lead to a better ability to adapt to environmental stressors and changes.

In an invasive population like the Burmese pythons in South Florida, this could result in a broader or more rapid distribution.

So … super-snakes? Or no? Hunter told The Guardian that her study does not indicate a new species of super-snake has been unleashed on the Everglades. But her study’s results do suggest a possible greater range of habitats for the wild snakes today. This greater range could hamper already unsuccessful efforts to reduce or eliminate the almost 150,000 pythons that have decimated native species – including bobcats, foxes, rabbits and raccoons from the Florida Keys to north of Lake Okeechobee.

Pythons have been reported in Everglades National Park since the 1980s. According to an article in Popular Science, the first pythons were likely escaped pets, and a few pythons may have been released when a breeding facility was destroyed during Hurricane Andrew.

In 2000, scientists realized that there was an established python population in the Everglades. Since then, the snakes have swept across southern Florida.

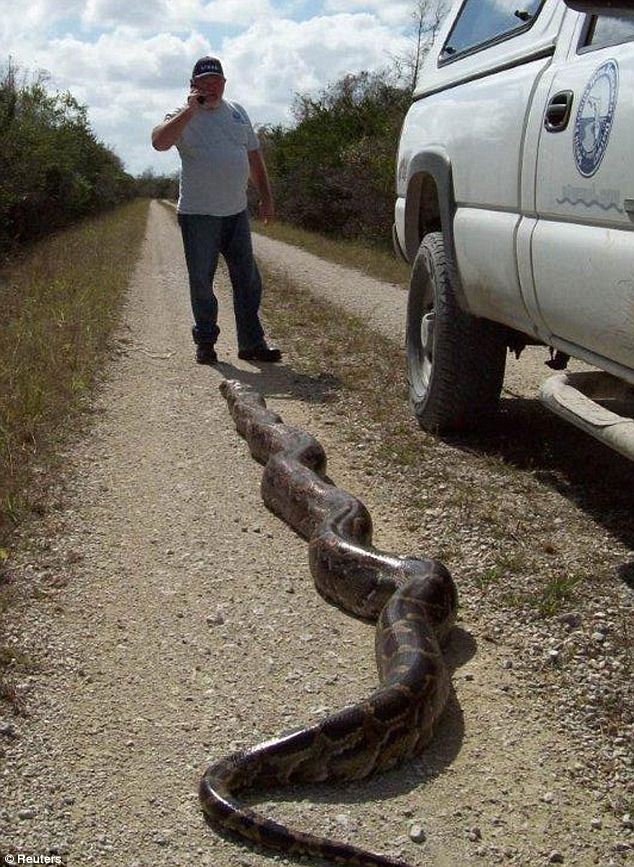

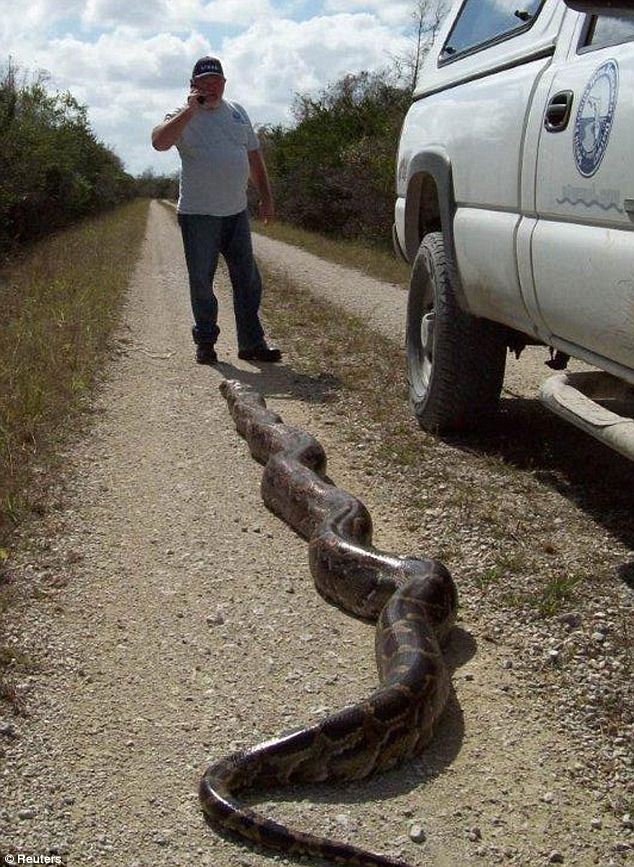

This 18-foot (5.5-meter) Burmese python captured and killed in the Everglades in 2014 is one of the largest pythons discovered there. Image via Daily Mail.

Here’s more from The Guardian:

Wildlife officials admit they are fighting a losing battle. Failed initiatives have included training dogs to sniff out the snakes and releasing pythons with radio transmitters to lead hunters to females carrying up to 100 eggs at a time.

Probably the most audacious effort came last year when two renowned snake catchers from India’s mountain-dwelling Irula tribe chanted their way across the Everglades for two months. They bagged 33 pythons. But that figure, like the 1,000-plus snakes killed to date in civilian hunting programs, is a drop in the ocean.

Burmese python in Everglades National Park. Image via R. Cammauf, National Park Service.

According to USGS, in the wild, related species typically avoid interbreeding by using different habitats. In their native Asia, Burmese pythons prefer wet habitats, while Indian pythons tend to stick to drier ones.

In previous studies, scientists have observed South Florida’s Burmese pythons in both wet and dry habitat types.

Scientists are not unhopeful, however. Kristen Hart, a USGS research ecologist and a co-author on the study commented:

Our ability to detect Burmese pythons in the Greater Everglades has been limited by their effective camouflage and secretive behavior. By using genetic tools and techniques and continuing to monitor their movement patterns, we have been able to gain a better understanding of their habitat preferences and resource use.

The new information in this study will help scientists and wildlife managers better understand these invasive predators’ capacity to adapt to new environments.

Bottom line: Researchers from USGS report on a new genetic analysis of invasive pythons in South Florida.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Pe375q

A Burmese python coiled in the grass in South Florida. Image via Bryan Falk, USGS.

Pythons are an invasive species in South Florida, originally brought there by humans. Since 2000, when wildlife experts realized that pythons have a sizable population in Florida, scientists have been trying to study these creatures, trying to understand how to control them. Scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reported on August 21, 2018, on a new genetic study showing that many of Florida’s pythons are closely related to one another. In fact, most of them are genetically related as first or second cousins. The study also found that at least a few of the snakes in the invasive South Florida population are not 100 percent Burmese pythons. Instead, the genetic evidence shows at least 13 snakes out of about 400 studied are a cross between two separate species: Burmese pythons, which mostly inhabit wetlands, and Indian pythons, which prefer higher ground.

Does this mean that an entirely new species – a super-snake, as many media outlets suggest – has emerged or is emerging in South Florida?

Margaret Hunter is lead author of the new study, published August 19 in the peer-reviewed journal Ecology and Evolution In a statement, she said the South Florida pythons:

… spring from a tangled family tree, with consequences for the species’ future spread that are hard to predict …

Sometimes interbreeding between related species can lead to hybrid vigor, that is, the best traits of two species are passed onto their offspring. Hybrid vigor can potentially lead to a better ability to adapt to environmental stressors and changes.

In an invasive population like the Burmese pythons in South Florida, this could result in a broader or more rapid distribution.

So … super-snakes? Or no? Hunter told The Guardian that her study does not indicate a new species of super-snake has been unleashed on the Everglades. But her study’s results do suggest a possible greater range of habitats for the wild snakes today. This greater range could hamper already unsuccessful efforts to reduce or eliminate the almost 150,000 pythons that have decimated native species – including bobcats, foxes, rabbits and raccoons from the Florida Keys to north of Lake Okeechobee.

Pythons have been reported in Everglades National Park since the 1980s. According to an article in Popular Science, the first pythons were likely escaped pets, and a few pythons may have been released when a breeding facility was destroyed during Hurricane Andrew.

In 2000, scientists realized that there was an established python population in the Everglades. Since then, the snakes have swept across southern Florida.

This 18-foot (5.5-meter) Burmese python captured and killed in the Everglades in 2014 is one of the largest pythons discovered there. Image via Daily Mail.

Here’s more from The Guardian:

Wildlife officials admit they are fighting a losing battle. Failed initiatives have included training dogs to sniff out the snakes and releasing pythons with radio transmitters to lead hunters to females carrying up to 100 eggs at a time.

Probably the most audacious effort came last year when two renowned snake catchers from India’s mountain-dwelling Irula tribe chanted their way across the Everglades for two months. They bagged 33 pythons. But that figure, like the 1,000-plus snakes killed to date in civilian hunting programs, is a drop in the ocean.

Burmese python in Everglades National Park. Image via R. Cammauf, National Park Service.

According to USGS, in the wild, related species typically avoid interbreeding by using different habitats. In their native Asia, Burmese pythons prefer wet habitats, while Indian pythons tend to stick to drier ones.

In previous studies, scientists have observed South Florida’s Burmese pythons in both wet and dry habitat types.

Scientists are not unhopeful, however. Kristen Hart, a USGS research ecologist and a co-author on the study commented:

Our ability to detect Burmese pythons in the Greater Everglades has been limited by their effective camouflage and secretive behavior. By using genetic tools and techniques and continuing to monitor their movement patterns, we have been able to gain a better understanding of their habitat preferences and resource use.

The new information in this study will help scientists and wildlife managers better understand these invasive predators’ capacity to adapt to new environments.

Bottom line: Researchers from USGS report on a new genetic analysis of invasive pythons in South Florida.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Pe375q

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire