NASA Earth Observatory reported this week (May 23, 2018) on a new, first-of-its-kind study, combining 14 years of satellite observations with data on human activities, showing where and how freshwater is changing on Earth. When we say freshwater, we’re speaking of the water found in lakes, rivers, soil, snow, groundwater and ice. The peer-reviewed journal Nature published the study on May 16. Hydrologist Jay Famiglietti of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a study co-author, summed up the results when he said:

What we are witnessing is major hydrologic change. We see a distinctive pattern of the wet land areas of the world getting wetter—those are the high latitudes and the tropics—and the dry areas in between getting drier. Embedded within the dry areas, we see multiple hot spots resulting from groundwater depletion.

The study authors attribute the changes to a variety of factors, including water management, climate change, and natural cycles.

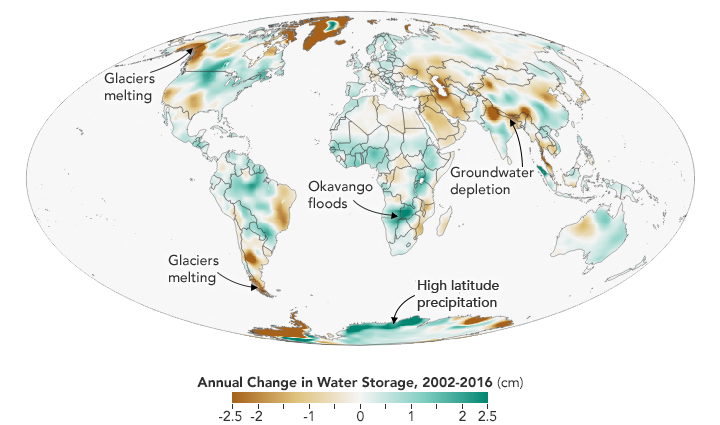

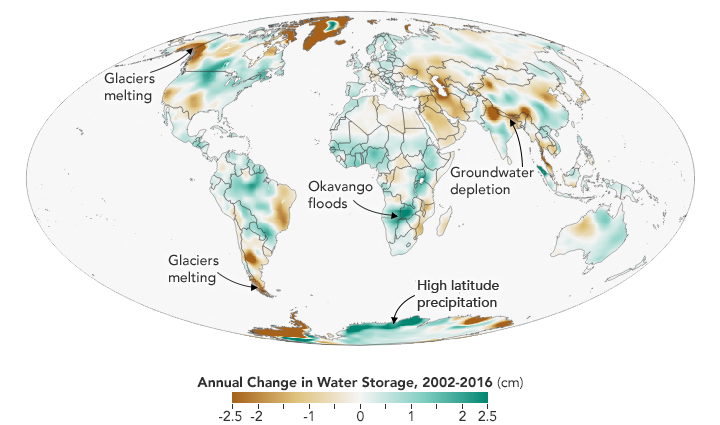

This map above depicts changes in water storage on Earth—on the surface, underground, and locked in ice and snow—between 2002 and 2016. Shades of green represent areas where freshwater levels have increased, while browns depict areas where they have been depleted. Image via NASA Earth Observatory

The research team analyzed 14 years of observations from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite to track trends in freshwater in 34 regions around the world. To put those trends in context, the scientists correlated GRACE findings with precipitation data from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project; with land cover imagery and data from Landsat; with irrigation maps; and with published reports of human activities in agriculture, mining, and reservoir operations.

Hydrologist Matt Rodell of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, is the study lead author. He said:

A key goal was to distinguish shifts in terrestrial water storage caused by natural variability — wet periods and dry periods associated with El Niño and La Niña, for example — from trends related to climate change or human impacts, like pumping groundwater out of an aquifer faster than it is replenished.

Famiglietti commented that while some water loss, such as melting ice sheets and alpine glaciers, is driven by a warming global climate, more time and data are needed to determine the driving forces behind other patterns of freshwater change. He said:

The pattern of wet-getting-wetter, dry-getting-drier during the rest of the 21st century is predicted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change models. But we’ll need a much longer dataset to be able to definitively say whether climate change is responsible for the emergence of any similar pattern in the GRACE data.

The NASA Earth Observatory post had other interesting things to say about freshwater within specific usages (for example, to grow food) and in specific parts of the world. Read more at NASA Earth Observatory.

Satellite images of Lake Cachuma—which supplies Santa Barbara with drinking water on October 27, 2013, and October 26, 2016. The sharp decline in water levels has exposed much of the bottom of the reservoir. Image via NASA.

Satellite image of agricultural operations in Saudi Arabia’s Wadi As-Sirhan Basin, January 17, 2012. Image via NASA.

The great Okavango Delta in the Kalahari Desert is illuminated in the sun’s reflection point in this panorama taken from the International Space Station on June 6, 2014. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: A new study that maps where global freshwater is changing finds that Earth’s wet landscapes are getting wetter and dry areas are getting drier.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2s9WdEk

NASA Earth Observatory reported this week (May 23, 2018) on a new, first-of-its-kind study, combining 14 years of satellite observations with data on human activities, showing where and how freshwater is changing on Earth. When we say freshwater, we’re speaking of the water found in lakes, rivers, soil, snow, groundwater and ice. The peer-reviewed journal Nature published the study on May 16. Hydrologist Jay Famiglietti of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a study co-author, summed up the results when he said:

What we are witnessing is major hydrologic change. We see a distinctive pattern of the wet land areas of the world getting wetter—those are the high latitudes and the tropics—and the dry areas in between getting drier. Embedded within the dry areas, we see multiple hot spots resulting from groundwater depletion.

The study authors attribute the changes to a variety of factors, including water management, climate change, and natural cycles.

This map above depicts changes in water storage on Earth—on the surface, underground, and locked in ice and snow—between 2002 and 2016. Shades of green represent areas where freshwater levels have increased, while browns depict areas where they have been depleted. Image via NASA Earth Observatory

The research team analyzed 14 years of observations from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite to track trends in freshwater in 34 regions around the world. To put those trends in context, the scientists correlated GRACE findings with precipitation data from the Global Precipitation Climatology Project; with land cover imagery and data from Landsat; with irrigation maps; and with published reports of human activities in agriculture, mining, and reservoir operations.

Hydrologist Matt Rodell of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, is the study lead author. He said:

A key goal was to distinguish shifts in terrestrial water storage caused by natural variability — wet periods and dry periods associated with El Niño and La Niña, for example — from trends related to climate change or human impacts, like pumping groundwater out of an aquifer faster than it is replenished.

Famiglietti commented that while some water loss, such as melting ice sheets and alpine glaciers, is driven by a warming global climate, more time and data are needed to determine the driving forces behind other patterns of freshwater change. He said:

The pattern of wet-getting-wetter, dry-getting-drier during the rest of the 21st century is predicted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change models. But we’ll need a much longer dataset to be able to definitively say whether climate change is responsible for the emergence of any similar pattern in the GRACE data.

The NASA Earth Observatory post had other interesting things to say about freshwater within specific usages (for example, to grow food) and in specific parts of the world. Read more at NASA Earth Observatory.

Satellite images of Lake Cachuma—which supplies Santa Barbara with drinking water on October 27, 2013, and October 26, 2016. The sharp decline in water levels has exposed much of the bottom of the reservoir. Image via NASA.

Satellite image of agricultural operations in Saudi Arabia’s Wadi As-Sirhan Basin, January 17, 2012. Image via NASA.

The great Okavango Delta in the Kalahari Desert is illuminated in the sun’s reflection point in this panorama taken from the International Space Station on June 6, 2014. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: A new study that maps where global freshwater is changing finds that Earth’s wet landscapes are getting wetter and dry areas are getting drier.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2s9WdEk

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire