A snowy morning scene in March 2018 at the Ocean Grove pier in New Jersey. Posted to EarthSky Facebook by John Entwistle.

A new study – published March 13, 2018, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications – again links warming Arctic temperatures to colder weather. Although this correlation is far-from-settled science, these particular researchers did find that severe winter weather in the eastern U.S. is two to four times more likely when the Arctic is abnormally warm than when the Arctic is abnormally cold. Likewise, according to this study, northern latitudes of Europe and Asia may have colder winters when the Arctic is warm. This research has drawn fire from global warming deniers and prompted contrarian viewpoints in some publications. How can we know who or what to believe?

Here’s what we can know, with some confidence. Measurements show that the Arctic has been abnormally warm, and sea ice in the Arctic has been low. Measurements have their uncertainties also, but many measurements – for example, sea ice measurements from the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado – show these trends in the Arctic. It appears that the Arctic is not only warming, but warming at a rate two to three times faster than the observed rate of warming for the rest of the globe. This phenomenon is known among climate scientists as Arctic amplification.

Explainer: How do scientists measure global temperature?

At the same time, as many of us know, the winter of 2017-2018 was extreme. There were record-breaking polar vortex disruptions, severe bomb cyclones and nor’easters in the U.S. Northeast and record-breaking cold and snow in the U.S. and Europe.

So … what’s happening here? It seems counterintuitive that a warmer Arctic would cause colder winters.

Should we believe this new study?

View larger. | Geographic locations of cities analyzed in the new study. The authors said: “We chose a geographically diverse set of 12 cities to analyze Arctic variability and severe winter weather, though we chose more cities in the northeastern and mid-western U.S. where severe winter weather is more common than in other regions of the U.S.” Image via Cohen et al.

In deciding whether you believe it, it’s important to realize that measurements are in a different category in science from analysis. The March 13 study – authored by Judah Cohen of MIT, Karl Pfeiffer of Atmospheric & Environmental Research, Inc. and Jennifer Francis of Rutgers – used the tools of science to analyze existing data. These authors described their study as an:

… extensive, quantitative analysis of the link between Arctic variability and severe winter weather across the mid-latitudes. In this study we find a robust relationship between Arctic temperatures and severe winter weather in the United States. When the Arctic is warm, both cold temperatures and heavy snowfall are more frequent compared to when the Arctic is cold.

Jennifer Francis commented in a statement from Rutgers on March 13:

Basically, this confirms the story I’ve been telling for a couple of years now. Warm temperatures in the Arctic cause the jet stream to take these wild swings, and when it swings farther south, that causes cold air to reach farther south.

These researchers found that when Arctic warming occurred near Earth’s surface, the correlation with severe winter weather was weak. But when the warming over the Arctic extended high in the atmosphere, into the stratosphere, disruptions of the stratospheric polar vortex were likely.

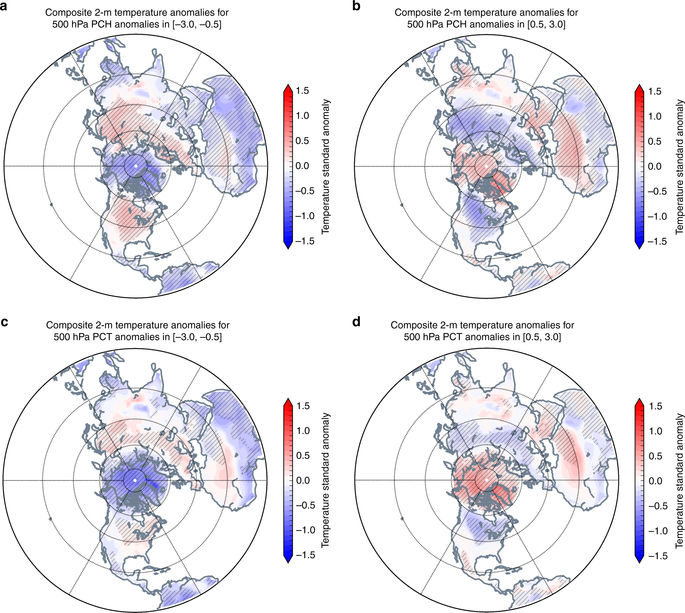

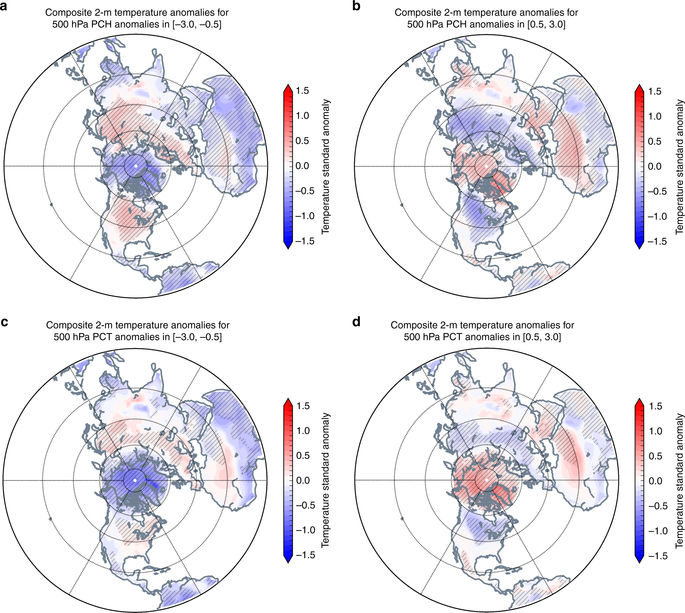

View larger. | These authors assert in their study that: “As the Arctic warms, the continents become colder.” See a complete explanation of this image via Cohen et al.

Global warming skeptics pounced on this study. For example, Steven Milloy – who is, among other things, the publisher of the website JunkScience.com, a former columnist for Fox News and a co-creator and manager of the Free Enterprise Action Fund – posted the following tweet, which lifts language directly from Cohen et al’s Nature paper.:

Boom… Nature study admissions undercut almost all climate studies:

1. Correlation not causation.

2. Historical record inadequate.

3. Physical mechanism not understood.

https://t.co/hV4Ov5algS pic.twitter.com/pVv6Iirlgn— Steve Milloy (@JunkScience) March 14, 2018

He’s pointing to the part of Cohen, Pfeiffer and Francis’ own study where they themselves point out some of this study’s unknowns and challenges, and, by extension, some of the unknowns and challenges inherent in modern climate science. Do these acknowledged unknowns and challenges undercut this study – or almost all climate studies – as Milloy suggests?

Let’s look at the answer in a wider context. Does asking scientific questions in any field suggest that area of science is not worth pursuing?

Of course not.

If it did, science as a whole would have come to a dead standstill long ago, and our lives would be far less easy and comfortable than they are today. Think of electricity. Do you suppose Thomas Edison had questions, as he figured it out? Do you think he might have had challenges?

The fact is, scientists are supposed to question themselves and each other. They’re supposed to work through challenges. It’s what they’re trained to do. It’s how science gets done. It might be helpful here to mention that all science is a process, as all scientists and many non-scientists know. Scientists question, and try to answer their own questions or learn how other scientists have answered them, and this constant questioning-and-answering pushes their investigations of nature forward … or, I should say, our investigations of nature, since science is a cultural activity, paid for in large part by our tax dollars.

Do global warming skeptics like Steven Milloy understand that questioning is part of the process of science? I have no idea. It’s possible he doesn’t; he’s trained as a lawyer, not a scientist.

Should we believe that Arctic warming is correlated with colder winters as this study suggests? Belief or disbelief doesn’t enter into it, for scientists, and it shouldn’t for you either. The results are just out there, for you and me to read about, be informed about and think about, and for future scientific studies to either confirm or refute.

This study is one small clue in the investigation of climate change, which has already been going on for decades. Will this one little clue be swept away by better ones? Maybe. Time will tell.

Until then, claims that the study has been undercut because scientists are questioning themselves and each other … well, those claims just show some writers’ ignorance of – unawareness of, unconsciousness of, unfamiliarity with, inexperience with, lack of information about – the way science works.

IT may be willful ignorance, or not.

See how Step #5 (Make a Conclusion) has an arrow leading back to Step #1 (Ask a Question)? Scientists are continually questioning because science isn’t a body of facts; it’s a ways of investigating nature. Image via SlidePlayer.com.

By the way, someone is bound to ask in the comments who supported the study by Cohen, Pfeiffer and Francis. That is a valid and excellent question. For virtually any published science study, you can find a section at the very bottom called Acknowledgements. These authors’ acknowledgements are as follows:

We are grateful to Barbara Mayes-Boustead and Steve Hallberg for generously sharing with us the AWSSI [Accumulated Winter Season Severity Index] data. J.C. is supported by the National Science Foundation grants AGS-1303647 and PLR-1504361. J.F. is supported by NASA grant NNX14AH896 and NSF/ARCSS grant 1304097.

In his criticism of the study, Steven Milloy didn’t have as established a mechanism for mentioning who currently funds him, but he’s well-known for having been a paid advocate for Phillip Morris, ExxonMobil and other corporations. Read more about who funds Steven Milloy.

Wondering who funds EarthSky? Our small organization (five part-time employees) receives revenues from three sources: ads on this website, donations and sales in our store.

A cold winter, via Onepony/ Fotolia/ ScienceDaily.

Bottom line: A warm Arctic means colder, snowier winters in the northeastern U.S., according to a new study. You don’t have to believe it; just think about it.

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/2piXAjn

A snowy morning scene in March 2018 at the Ocean Grove pier in New Jersey. Posted to EarthSky Facebook by John Entwistle.

A new study – published March 13, 2018, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications – again links warming Arctic temperatures to colder weather. Although this correlation is far-from-settled science, these particular researchers did find that severe winter weather in the eastern U.S. is two to four times more likely when the Arctic is abnormally warm than when the Arctic is abnormally cold. Likewise, according to this study, northern latitudes of Europe and Asia may have colder winters when the Arctic is warm. This research has drawn fire from global warming deniers and prompted contrarian viewpoints in some publications. How can we know who or what to believe?

Here’s what we can know, with some confidence. Measurements show that the Arctic has been abnormally warm, and sea ice in the Arctic has been low. Measurements have their uncertainties also, but many measurements – for example, sea ice measurements from the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado – show these trends in the Arctic. It appears that the Arctic is not only warming, but warming at a rate two to three times faster than the observed rate of warming for the rest of the globe. This phenomenon is known among climate scientists as Arctic amplification.

Explainer: How do scientists measure global temperature?

At the same time, as many of us know, the winter of 2017-2018 was extreme. There were record-breaking polar vortex disruptions, severe bomb cyclones and nor’easters in the U.S. Northeast and record-breaking cold and snow in the U.S. and Europe.

So … what’s happening here? It seems counterintuitive that a warmer Arctic would cause colder winters.

Should we believe this new study?

View larger. | Geographic locations of cities analyzed in the new study. The authors said: “We chose a geographically diverse set of 12 cities to analyze Arctic variability and severe winter weather, though we chose more cities in the northeastern and mid-western U.S. where severe winter weather is more common than in other regions of the U.S.” Image via Cohen et al.

In deciding whether you believe it, it’s important to realize that measurements are in a different category in science from analysis. The March 13 study – authored by Judah Cohen of MIT, Karl Pfeiffer of Atmospheric & Environmental Research, Inc. and Jennifer Francis of Rutgers – used the tools of science to analyze existing data. These authors described their study as an:

… extensive, quantitative analysis of the link between Arctic variability and severe winter weather across the mid-latitudes. In this study we find a robust relationship between Arctic temperatures and severe winter weather in the United States. When the Arctic is warm, both cold temperatures and heavy snowfall are more frequent compared to when the Arctic is cold.

Jennifer Francis commented in a statement from Rutgers on March 13:

Basically, this confirms the story I’ve been telling for a couple of years now. Warm temperatures in the Arctic cause the jet stream to take these wild swings, and when it swings farther south, that causes cold air to reach farther south.

These researchers found that when Arctic warming occurred near Earth’s surface, the correlation with severe winter weather was weak. But when the warming over the Arctic extended high in the atmosphere, into the stratosphere, disruptions of the stratospheric polar vortex were likely.

View larger. | These authors assert in their study that: “As the Arctic warms, the continents become colder.” See a complete explanation of this image via Cohen et al.

Global warming skeptics pounced on this study. For example, Steven Milloy – who is, among other things, the publisher of the website JunkScience.com, a former columnist for Fox News and a co-creator and manager of the Free Enterprise Action Fund – posted the following tweet, which lifts language directly from Cohen et al’s Nature paper.:

Boom… Nature study admissions undercut almost all climate studies:

1. Correlation not causation.

2. Historical record inadequate.

3. Physical mechanism not understood.

https://t.co/hV4Ov5algS pic.twitter.com/pVv6Iirlgn— Steve Milloy (@JunkScience) March 14, 2018

He’s pointing to the part of Cohen, Pfeiffer and Francis’ own study where they themselves point out some of this study’s unknowns and challenges, and, by extension, some of the unknowns and challenges inherent in modern climate science. Do these acknowledged unknowns and challenges undercut this study – or almost all climate studies – as Milloy suggests?

Let’s look at the answer in a wider context. Does asking scientific questions in any field suggest that area of science is not worth pursuing?

Of course not.

If it did, science as a whole would have come to a dead standstill long ago, and our lives would be far less easy and comfortable than they are today. Think of electricity. Do you suppose Thomas Edison had questions, as he figured it out? Do you think he might have had challenges?

The fact is, scientists are supposed to question themselves and each other. They’re supposed to work through challenges. It’s what they’re trained to do. It’s how science gets done. It might be helpful here to mention that all science is a process, as all scientists and many non-scientists know. Scientists question, and try to answer their own questions or learn how other scientists have answered them, and this constant questioning-and-answering pushes their investigations of nature forward … or, I should say, our investigations of nature, since science is a cultural activity, paid for in large part by our tax dollars.

Do global warming skeptics like Steven Milloy understand that questioning is part of the process of science? I have no idea. It’s possible he doesn’t; he’s trained as a lawyer, not a scientist.

Should we believe that Arctic warming is correlated with colder winters as this study suggests? Belief or disbelief doesn’t enter into it, for scientists, and it shouldn’t for you either. The results are just out there, for you and me to read about, be informed about and think about, and for future scientific studies to either confirm or refute.

This study is one small clue in the investigation of climate change, which has already been going on for decades. Will this one little clue be swept away by better ones? Maybe. Time will tell.

Until then, claims that the study has been undercut because scientists are questioning themselves and each other … well, those claims just show some writers’ ignorance of – unawareness of, unconsciousness of, unfamiliarity with, inexperience with, lack of information about – the way science works.

IT may be willful ignorance, or not.

See how Step #5 (Make a Conclusion) has an arrow leading back to Step #1 (Ask a Question)? Scientists are continually questioning because science isn’t a body of facts; it’s a ways of investigating nature. Image via SlidePlayer.com.

By the way, someone is bound to ask in the comments who supported the study by Cohen, Pfeiffer and Francis. That is a valid and excellent question. For virtually any published science study, you can find a section at the very bottom called Acknowledgements. These authors’ acknowledgements are as follows:

We are grateful to Barbara Mayes-Boustead and Steve Hallberg for generously sharing with us the AWSSI [Accumulated Winter Season Severity Index] data. J.C. is supported by the National Science Foundation grants AGS-1303647 and PLR-1504361. J.F. is supported by NASA grant NNX14AH896 and NSF/ARCSS grant 1304097.

In his criticism of the study, Steven Milloy didn’t have as established a mechanism for mentioning who currently funds him, but he’s well-known for having been a paid advocate for Phillip Morris, ExxonMobil and other corporations. Read more about who funds Steven Milloy.

Wondering who funds EarthSky? Our small organization (five part-time employees) receives revenues from three sources: ads on this website, donations and sales in our store.

A cold winter, via Onepony/ Fotolia/ ScienceDaily.

Bottom line: A warm Arctic means colder, snowier winters in the northeastern U.S., according to a new study. You don’t have to believe it; just think about it.

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/2piXAjn

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire