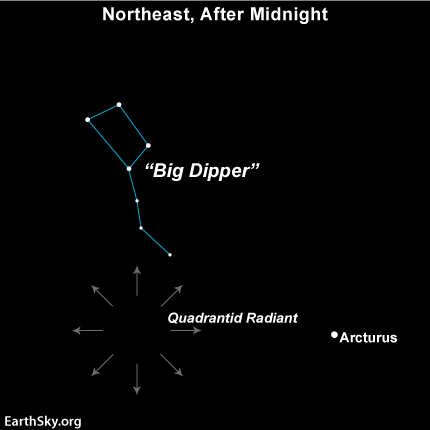

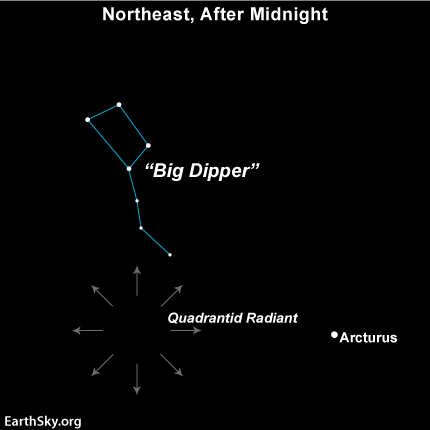

Next up … the Quadrantid meteor shower, which radiates from a far northern point in the sky and thus is best seen from northerly latitudes. In 2015, the expected peak night occurs from late night January 3 until dawn January 4, under the glare of the almost-full waxing gibbous moon. The peak is quite narrow, lasting for hours instead of days. So if you’re on the daylight side of the world when the peak hours of the shower are taking place, you’ll be out of luck. But if you’re up for the challenge, give this shower a try anyway, in the dark hour(s) before dawn on January 3 or January 4. Note that the moon will set earlier on January 3. Shortly before dawn, the moon will be low in the west, or will have already set. Click here to find out your moonset time. Sit in a moon shadow with an otherwise open view of the predawn sky, and if you’re really lucky, you might see as many as 40 meteors in one hour. Good luck!

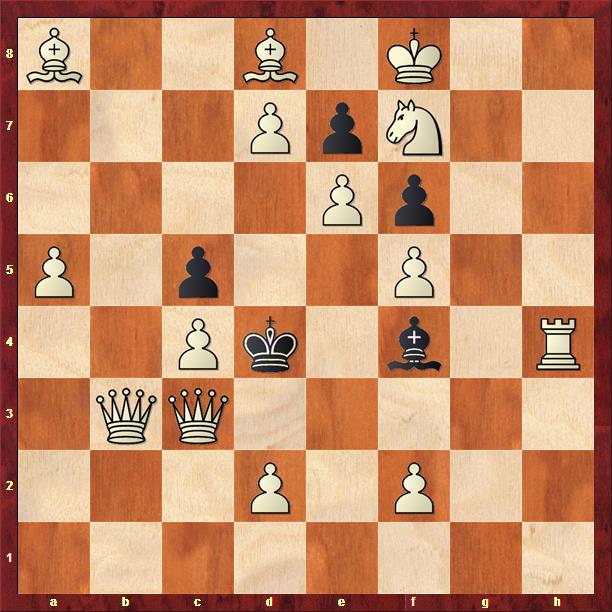

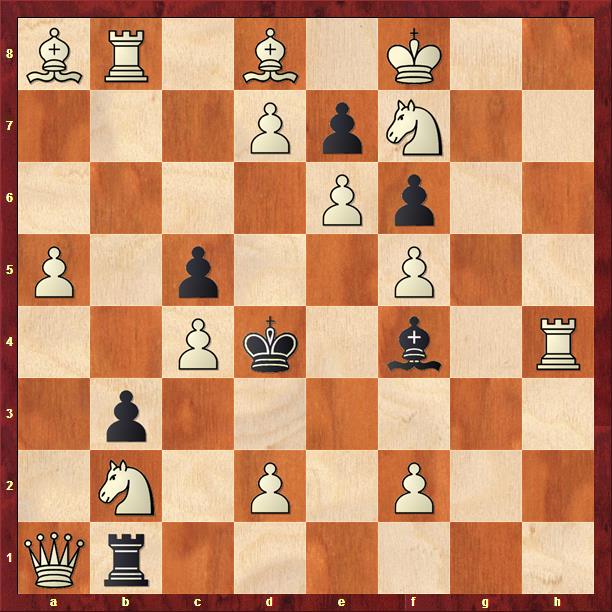

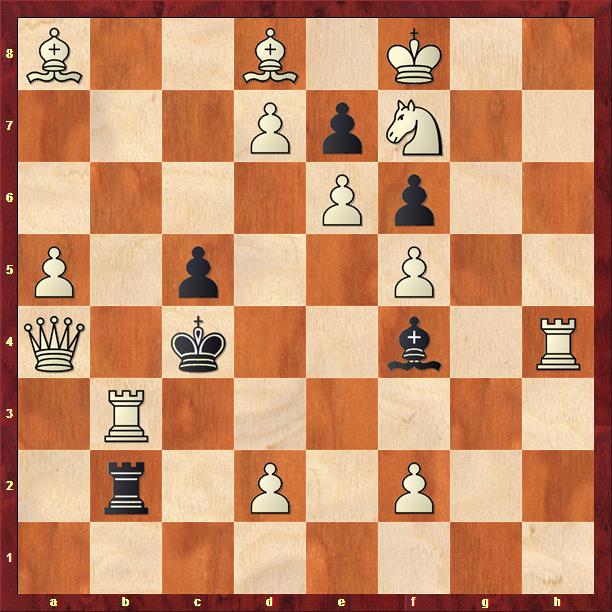

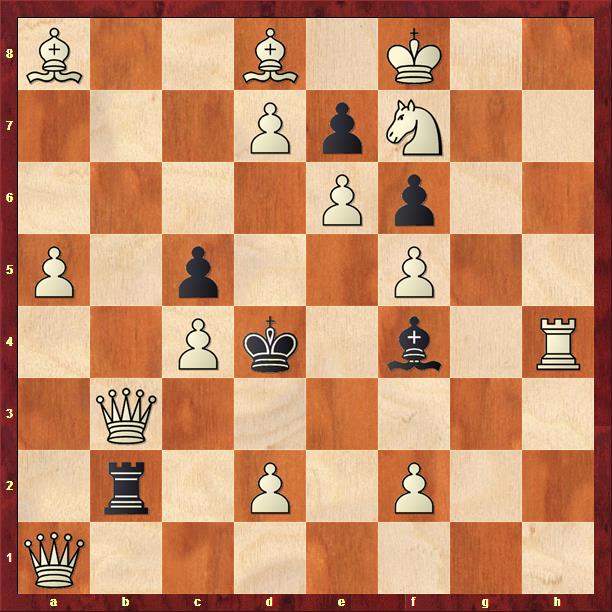

Quadrantid meteors fly in moonlight in early January 2015

Click the links below to learn more about meteor showers in 2015.

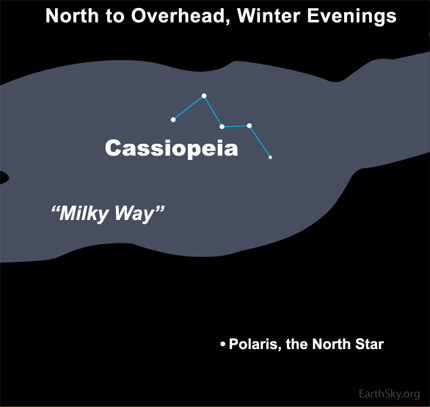

From mid-northern latitudes, the radiant point for the Quadrantid shower doesn’t climb over the horizon until after midnight.

January 3-4, 2015 Quadrantids

April 21-22, 2015 Lyrids

May 5-6, 2015 Eta Aquarids

July 27-28, 2015 Delta Aquarids

August 11-12, 2015 Perseids

October 8, 2015 Draconids

October 21-22, 2015 Orionids

November 4-5, 2015 South Taurids

November 12-13, 2015 North Taurids

November 17-18, 2015 Leonids

December 13-14, 2015 Geminids

A word about moonlight

Most important: a dark sky

Know your dates and times

Where to go to watch a meteor shower

What to bring with you

Are the predictions reliable?

Remember …

Easily locate stars and constellations during any day and time with EarthSky’s Planisphere.

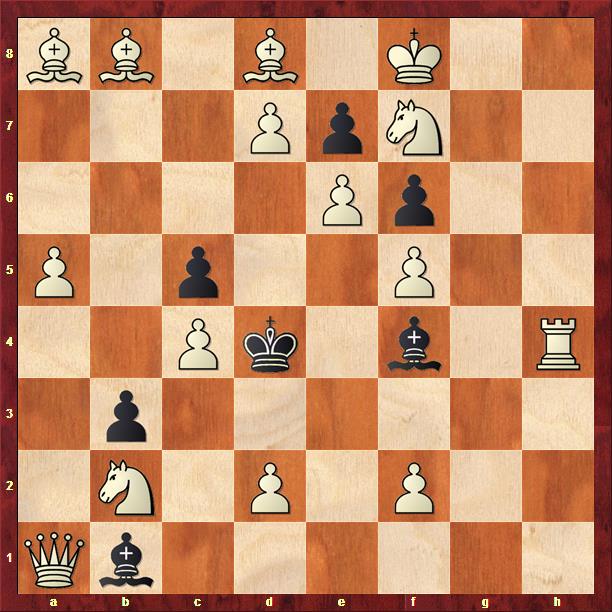

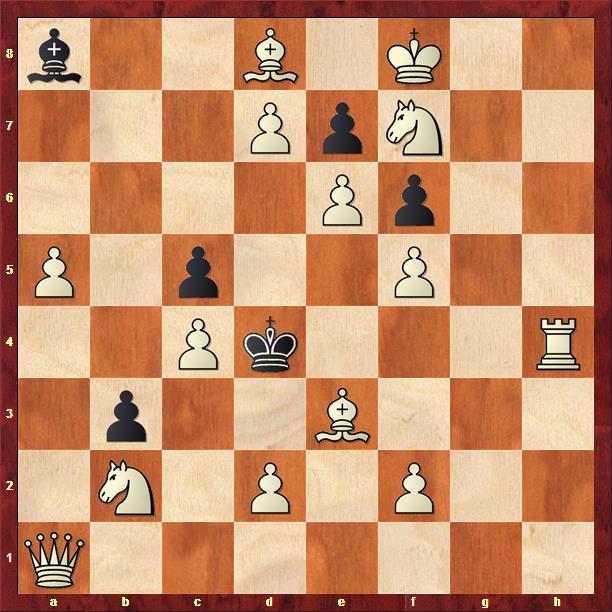

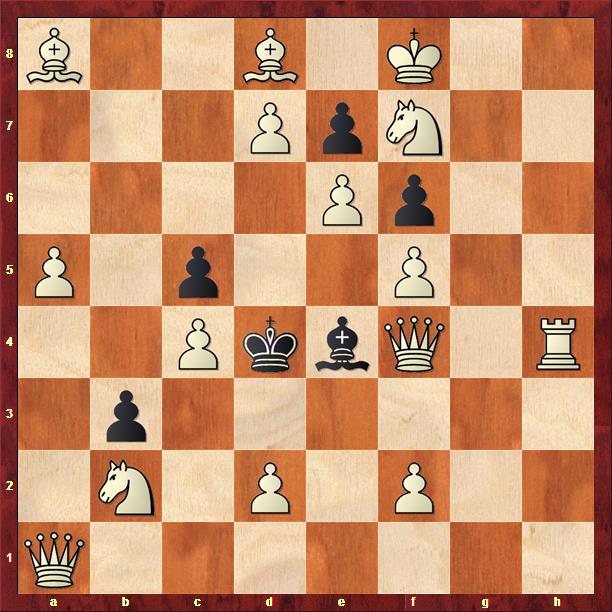

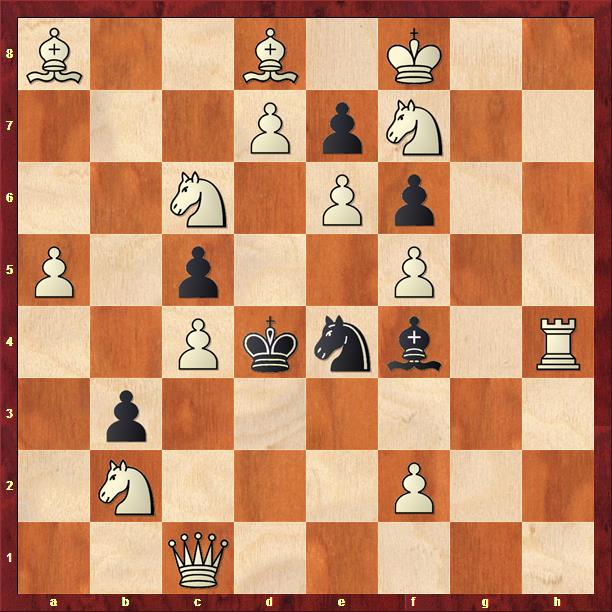

January 4, 2015 before dawn, the Quadrantids

Although the Quadrantids can produce over 100 meteors per hour, the sharp peak of this shower tends to last only a few hours, and doesn’t always come at an opportune time. In other words, you have to be in the right spot on Earth to view this meteor shower in all its splendor. The radiant point is in the part of the sky that used to be considered the constellation Quadrans Muralis the Mural Quadrant. You’ll find this radiant near the famous Big Dipper asterism (chart here), in the north-northeastern sky after midnight and highest up before dawn. Because the radiant is fairly far to the north on the sky’s dome, meteor numbers will be greater in the Northern Hemisphere. In 2015, watch in the wee hours – after midnight and before dawn – on January 4. Unfortunately, the almost-full waxing gibbous moon is out almost all night long, sitting low in the west in the dark hour before dawn. Click here to find out your moonset time..

Everything you need to know: Quadrantid meteor shower

April 22, 2015 before dawn, the Lyrids

The Lyrid meteor shower – April’s shooting stars – lasts from about April 16 to 25. Lyrid meteors tend to be bright and often leave trails. About 10-20 meteors per hour can be expected at their peak. Plus, the Lyrids are known for uncommon surges that can sometimes bring the rate up to 100 per hour. Those rare outbursts are not easy to predict, but they’re one of the reasons the tantalizing Lyrids are worth checking out around their peak morning. The radiant for this shower is near the bright star Vega in the constellation Lyra (chart here), which rises in the northeast at about 10 p.m. on April evenings. In 2015, the peak morning is April 22, but you might also see meteors before and after that date. The waxing crescent moon will set in the evening, leaving a dark for watching this year’s Lyrid shower.

Everything you need to know: Lyrid meteor shower

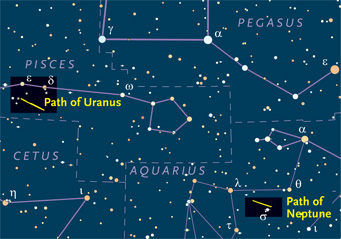

May 6, 2015 before dawn, the Eta Aquarids

This meteor shower has a relatively broad maximum – meaning you can watch it for several days around the predicted peak. However, in 2015, the bright waning gibbous moon is sure to diminish the numbers. The radiant is near the star Eta in the constellation Aquarius the Water Bearer (click here for chart). The radiant comes over the eastern horizon at about 4 a.m. local time; that is the time at all locations across the globe. For that reason, the hour or two before dawn tends to offer the most Eta Aquarid meteors, no matter where you are on Earth. At northerly latitudes – like those in the northern U.S. and Canada, or northern Europe, for example – the meteor numbers are typically lower for this shower. In the southern half of the U.S., 10 to 20 meteors per hour might be visible in a dark sky. Farther south – for example, at latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere – the meteor numbers may increase dramatically, with perhaps two to three times more Eta Aquarid meteors streaking the southern skies. For the most part, the Eta Aquarids is a predawn shower. In 2015, the bright waning gibbous moon will obscure thias year’s production. The most meteors will probably rain down on May 6, in the dark hours before dawn. But watch on May 5 and 7 as well! The broad peak to this shower means that some meteors may fly in the dark hour before dawn for a few days before and after the predicted optimal date.

Everything you need to know: Eta Aquarid meteor shower

Late July and early August, 2015, the Delta Aquarids

Like the Eta Aquarids in May, the Delta Aquarid meteor shower in July favors the Southern Hemisphere and tropical latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere. The meteors appear to radiate from near the star Skat or Delta in the constellation Aquarius the Water Bearer. The maximum hourly rate can reach 15-20 meteors in a dark sky. The nominal peak is around July 27-30, but, unlike many meteor showers, the Delta Aquarids lack a very definite peak. Instead, these medium-speed meteors ramble along fairly steadily throughout late July and early August. An hour or two before dawn usually presents the most favorable view of the Delta Aquarids. At the shower’s peak in late July, 2015, the rather faint Delta Aquarid meteors will have to contend with moonlight. The waxing gibbous moon will be out until the wee hours after midnight. Try watching in late July predawn sky, after moonset.

Everything you need to know: Delta Aquarid shower

August 11-12, 2015 before dawn, the Perseids

The Perseid meteor shower is perhaps the most beloved meteor shower of the year for the Northern Hemisphere. Fortunately, the slender waning crescent moon rising at or near dawn will not obtrude on this year’s shower. The Perseid shower builds gradually to a peak, often produces 50 to 100 meteors per hour in a dark sky at the peak, and, for us in the Northern Hemisphere, this shower comes when the weather is warm. The Perseids tend to strengthen in number as late night deepens into midnight, and typically produce the most meteors in the wee hours before dawn. They radiate from a point in the constellation Perseus the Hero, but, as with all meteor shower radiant points, you don’t need to know Perseus to watch the shower; instead, the meteors appear in all parts of the sky. They are typically fast and bright meteors. They frequently leave persistent trains. Every year, you can look for the Perseids to peak around August 10-13. Predicted peak mornings in 2015: August 11, 12 and 13. The Perseids combine with the Delta Aquarid shower (above) to produce a dazzling display of shooting stars on what are, for us in the N. Hemisphere, warm summer nights. In 2015, as always, the Perseid meteors will be building to a peak from early August until the peak nights; afterwards, they drop off fairly rapidly. With little or no moon to ruin the show, this is a great year for watching the Perseid meteor shower.

Everything you need to know: Perseid meteor shower

October 8, 2015, the Draconids

The radiant point for the Draconid meteor shower almost coincides with the head of the constellation Draco the Dragon in the northern sky. That’s why the Draconids are best viewed from the Northern Hemisphere. The Draconid shower is a real oddity, in that the radiant point stands highest in the sky as darkness falls. That means that, unlike many meteor showers, more Draconids are likely to fly in the evening hours than in the morning hours after midnight. This shower is usually a sleeper, producing only a handful of languid meteors per hour in most years. But watch out if the Dragon awakes! In rare instances, fiery Draco has been known to spew forth many hundreds of meteors in a single hour. In 2015, the waning crescent moon rises at late night and will not intrude on this year’s Draconid shower. Try watching at nightfall and early evening on October 7 and 8.

Everything you need to know: Draconid Meteor shower

October 22, 2015 before dawn, the Orionids

On a dark, moonless night, the Orionids exhibit a maximum of about 10 to 20 meteors per hour. The waxing gibbous moon will be out the during the evening hours, but it’ll set before the prime time viewing hours, providing deliciously dark skies for this year’s Orionid shower. More meteors tend to fly after midnight, and the Orionids are typically at their best in the wee hours before dawn. These fast-moving meteors occasionally leave persistent trains. They sometimes produce bright fireballs, so watch for them to flame in the sky. If you trace these meteors backward, they seem to come from the Club of the famous constellation Orion the Hunter. You might know Orion’s bright, ruddy star Betelgeuse. The radiant is north of Betelgeuse. The Orionids have a broad and irregular peak that isn’t easy to predict. This year, 2015, presents a fine year for watching the Orionid meteor shower. The best viewing for the Orionids in 2015 will probably be before dawn on October 22. Try the days before and after that, too, sticking to the midnight-to-dawn hours..

Everything you need to know: Orionid meteor shower

Late night November 4 until dawn November 5, 2015, the South Taurids

Fortunately, the full moon will wash away all but the brightest South Taurid meteors. The meteoroid streams that feed the South (and North) Taurids are very spread out and diffuse. That means the Taurids are extremely long-lasting (September 25 to November 25) but usually don’t offer more than about 7 meteors per hour. That is true even on the South Taurids’ expected peak night. The Taurids are, however, well known for having a high percentage of fireballs, or exceptionally bright meteors. Plus, the other Taurid shower – the North Taurids – always adds a few more meteors to the mix during the South Taurids’ peak night. In 2015, the slim waning crescent moon coming up before dawn will not seriously obtrude on this year’s South Taurid meteor shower. The South Taurids should produce their greatest number of meteors in the wee hours – between midnight and dawn – on November 5. Remember, it’ll be possible to catch a fireball or two!

Late night November 12 until dawn November 13, 2015, the North Taurids

Like the South Taurids, the North Taurids meteor shower is long-lasting (October 12 – December 2) but modest, and the peak number is forecast at about 7 meteors per hour. The North and South Taurids combine, however, to provide a nice sprinkling of meteors throughout October and November. Typically, you see the maximum numbers at around midnight, when Taurus the Bull is highest in the sky. Taurid meteors tend to be slow-moving, but sometimes very bright. In 2015, the new moon comes only one day before the predicted peak, providing a dark sky for the 2015 North Taurid shower.

Late night November 17 until dawn November 18, 2015, the Leonids

Radiating from the constellation Leo the Lion, the famous Leonid meteor shower has produced some of the greatest meteor storms in history – at least one in living memory, 1966 – with rates as high as thousands of meteors per minute during a span of 15 minutes on the morning of November 17, 1966. Indeed, on that beautiful night in 1966, the meteors did, briefly, fall like rain. Some who witnessed the 1966 Leonid meteor storm said they felt as if they needed to grip the ground, so strong was the impression of Earth plowing along through space, fording the meteoroid stream. The meteors, after all, were all streaming from a single point in the sky – the radiant point – in this case in the constellation Leo the Lion. Leonid meteor storms sometimes recur in cycles of 33 to 34 years, but the Leonids around the turn of the century – while wonderful for many observers – did not match the shower of 1966. And, in most years, the Lion whimpers rather than roars, producing a maximum of perhaps 10-15 meteors per hour on a dark night. Like many meteor showers, the Leonids ordinarily pick up steam after midnight and display the greatest meteor numbers just before dawn. In 2015, the rather wide waxing crescent moon sets in the evening and won’t interfere with this year’s Leonid meteor shower. The peak morning will probably be November 18 – but try November 17, too.

Everything you need to know: Leonid meteor shower

December 13-14, 2015, mid-evening until dawn, Geminids

Radiating from near the bright stars Castor and Pollux in the constellation Gemini the Twins, the Geminid meteor shower is one of the finest meteors showers visible in either the Northern or the Southern Hemisphere. Best yet, there is no moon to obscure the 2015 Geminid shower. The meteors are plentiful, rivaling the August Perseids, with perhaps 50 to 100 meteors per hour visible at the peak. Plus Geminid meteors are often bright. These meteors are often about as good in the evening as in the hours between midnight and dawn. In 2015, the slender waxing crescent moon will set soon after the sun, providing a wonderful cover of darkness for the Geminid meteor shower. Your best bet is to watch on December 12-13 and 13-14, from mid-evening (9 to 10 p.m.) until dawn.

Animation Credit: NASA MSFC

A word about moonlight. In 2015, moonlight will not pose much of a problem for the April Lyrids, August Perseids, October Draconids, October Orionids, November South Taurids, November North Taurids, November Leonids and December Geminids. There’s some moon-free viewing time for the July Delta Aquarids. The nearly full moon gets in the way of the January Quadrantids and May Eta Aquarids. Our almanac page provides links for access to the moonrise and moonset times in your sky.

Most important: a dark sky. Here’s the first thing – the main thing – you need to know to become as proficient as the experts at watching meteors. That is, to watch meteors, you need a dark sky. It’s possible to catch a meteor or two or even more from the suburbs. But, to experience a true meteor shower – where you might see several meteor each minute – avoid city lights.

Know your dates and times. You also need to be looking on the right date, at the right time of night. Meteor showers occur over a range of dates, because they stem from Earth’s own movement through space. As we orbit the sun, we cross “meteor streams.” These streams of icy particles in space come from comets moving in orbit around the sun. Comets are fragile icy bodies that litter their orbits with debris. When this cometary debris enters our atmosphere, it vaporizes due to friction with the air. If moonlight or city lights don’t obscure the view, we on Earth see the falling, vaporizing particles as meteors. The Lyrids take place between about April 16 and 25. The peak morning in 2015 should be April 22, but you might catch Lyrid meteors on the nights around that date as well.

Where to go to watch a meteor shower. You can comfortably watch meteors from many places, assuming you have a dark sky: a rural back yard or deck, the hood of your car, the side of a road. State parks and national parks are good bets, but be sure they have a wide open viewing area, like a field; you don’t want to be stuck in the midst of a forest on meteor night. An EarthSky friend and veteran meteor-watcher and astrophotographer Sergio Garcia Rill also offers this specific advice:

… you might want to give it a try but don’t know where to go. Well, in planning my night photoshoots I use a variety of apps and web pages to know how dark the sky is in a certain location, the weather forecast, and how the night sky will look. Here’s the link to Dark Sky Finder. It’s a website that shows the light pollution in and around cities in North America which has been fundamental for finding dark sites to setup shots. Dark Sky finder also has an app for iPhone and iPad which as of this writting is only 99 cents so you might want to look into that as well. For people not in North America, the Blue Marble Navigator might be able to help to see how bright are the lights near you.

The other tool I can suggest is the Clear Sky Chart. I’ve learned the hard way that, now matter how perfectly dark the sky is at your location, it won’t matter if there’s a layer of clouds between you an the stars. This page is a little hard to read, but it shows a time chart, with each column being an hour, and each row being one of the conditions like cloud coverage and darkness. Alternatively, you could try to see the regular weather forecast at the weather channel or your favorite weather app.

What to bring with you. You don’t need special equipment to watch a meteor shower. If you want to bring along equipment to make yourself more comfortable, consider a blanket or reclining lawn chair, a thermos with a hot drink, binoculars for gazing at the stars. Be sure to dress warmly enough, even in spring or summer, especially in the hours before dawn. Binoculars are fun to have, too. You won’t need them for watching the meteor shower, but, especially if you have a dark sky, you might not be able to resist pointing them at the starry sky.

Are the predictions reliable? Although astronomers have tried to publish exact predictions in recent years, meteor showers remain notoriously unpredictable. Your best bet is to go outside at the times we suggest, and plan to spend at least an hour, if not a whole night, reclining comfortably while looking up at the sky. Also remember that meteor showers typically don’t just happen on one night. They span a range of dates. So the morning before or after a shower’s peak might be good, too.

Remember … meteor showers are like fishing. You go, you enjoy nature … and sometimes you catch something.

Peak dates are derived from data published in the Observer’s Handbook by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and Guy Ottewell’s Astronomical Calendar .

Dick Dionne in Green Valley, Arizona caught this bright Taurid fireball on November 15, 2014. Many reported fireballs in early November this year! Bright objects in upper left of this photo are the moon and planet Jupiter.

EarthSky Facebook friend Eddie Popovits caught this Perseid fireball in early August 2014.

View larger. | Simon Waldram in the Canary Islands caught this Lyrid meteor on the night of April 20-21, 2014. This year’s Lyrid meteor shower was plagued by bright moonlight.

Mike O’Neal posted this shot of a Lyrid meteor on the EarthSky Facebook page at last year’s shower, on April 22, 2013. He wrote, ‘Had mostly cloudy sky, but did see some beautiful ones between the breaks.’

A North Taurid meteor seen fleeing its radiant point near the Pleiades in the constellation Taurus. Captured by EarthSky Facebook friend Abhijit Juvekar on November 12, 2013. Thank you, Abhijit!

View larger. | Scott MacNeill created this wonderful composite image of 2013 Perseid meteors at Frosty Drew Observatory in Charlestown, Rhode Island, USA. We love this image, because you can see the meteors coming from their radiant point in the constellation Perseus. Thank you, Scott! Visit Scott’s website, Exit Pupil Creative Workshop.

From EarthSky Facebook friend Guy Livesay. He wrote, ‘ Didn’t see many Lyrids on the 21st or 22nd in Eastern NC. This is from the 21st. There’s actually 2 in this shot very close together.’

Taurid meteor seen by EarthSky Facebook friend Forrest Boone on November 9, 2012 over North Carolina. Thanks, Forrest!

The Draconid meteor shower put on a fabulous display in October of last year (2011). European observers saw over 600 meteors per hour. Image copyright: Frank Martin Ingilæ. Used with permission. Click here to expand.

EarthSky Facebook friend Dave Walker caught this 2012 Perseid meteor on the morning of August 12, 2012.

EarthSky Facebook friend Brian Emfinger created this amazing composite view during the 2012 Perseid meteor shower. Perseid meteors tend to cross the sky one by one. But this photo captures what you can expect to see during a burst of meteors – when several at once cross the sky – or during a particularly rich meteor display. Fantastic image Brian! Thank you.

An Eta Aquarid meteor streaks over northern Georgia on April 29, 2012. Image credit: NASA/MSFC/B. Cooke

This Geminid meteor is seen coming straight from its radiant point, which is near the two brightest stars in Gemini, Castor and Pollux. Photo taken on the night of December 12-13, 2012 by EarthSky Facebook friend Mike O’Neal in Oklahoma. He said the 2012 Geminid meteor shower was one of the best meteor shows he’s ever seen.

Bottom line: The Quadrantid meteor shower is next on the night of January 2-3, 2015. Details on how to watch, plus listings of all major meteor showers in 2015.

EarthSky’s top 10 tips for meteor-watchers

from EarthSky http://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/earthskys-meteor-shower-guide