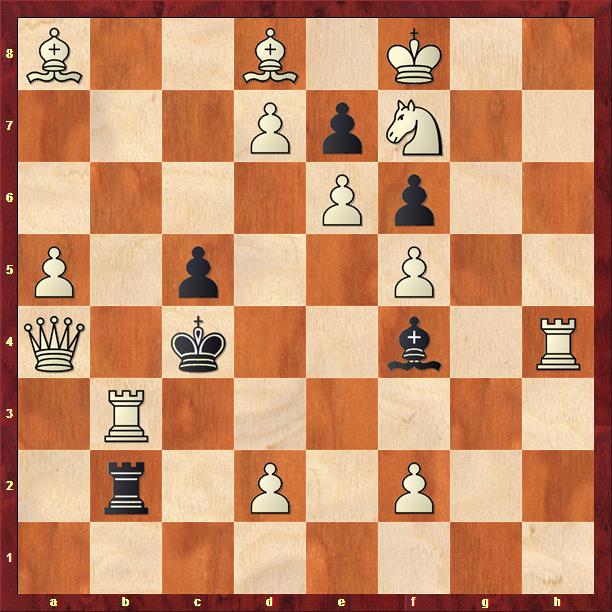

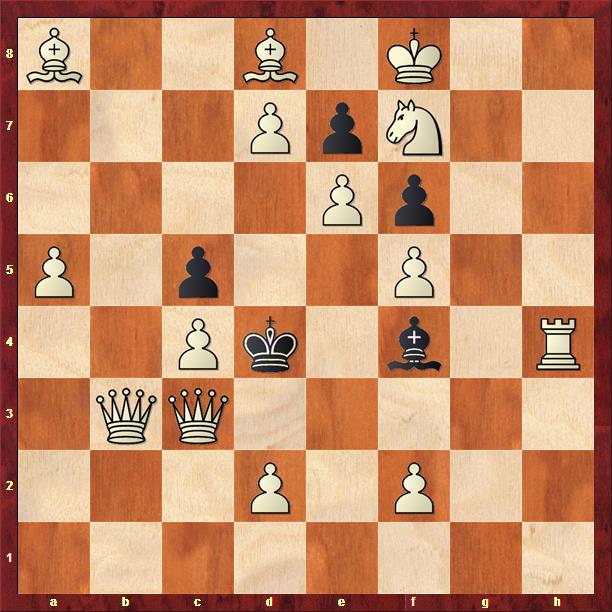

Well, it’s taken me longer to get back to this than I originally planned, but how about a second look at the Babson Task? The problem below was composed by Leonid Yarosh, in 1983. It’s white to move and mate in four:

Remember that white is always moving up the board and black is always moving down. So, black’s pawn on a2 is poised to promote.

Folks, this is one of the most famous diagrams in the history of chess composition. Why? It’s one of the first direct mates to show the Babson Task, and the first to show the task with an acceptable key. (The absolute first had a key that involved white capturing a black piece, which is a major aesthetic faux pas, even in a problem showing a remarkable task).

We have considered the Babson Task before. The task calls for four variations. In each, the same black pawn promotes to one of the four possible pieces. White must answer each each promotion by promoting a pawn to the same kind of piece. So, if black defends against a threat by promoting to a queen, then white must answer with a queen promotion of his own. If black promotes to a rook, then white must also promote to a rook. Of course, when I say that white must promote to a rook I mean that any other move would not allow him to complete the stipulation.

Now, before moving on to the solution, I want to introduce some problem jargon for you. Typically a problem has a theme, which can be thought of as the main strategic or tactical point the composition was meant to illustrate. Certain variations in the problem contribute to that theme. Often, though, the composer finds it necessary to include other variations whose sole purpose is to make the problem sound. They do not contribute to the theme. Such variations are referred to as by-play. An excessive amount of by-play is usually considered an aesthetic weakness, since it distracts from the theme of the problem. On the other hand, if the by-play is itself tactically interesting it can sometimes enhance a problem.

Anyway, this problem has a ton of by-play. I will ignore nearly all of it. You can check out this discussion if you want to explore more of this problem’s subtleties.

Time to get down to business. If the black queen could be distracted from its defense of the bishop on f4, then white would have a powerful threat in the move Rxf4. This suggests the key move: 1. a7!

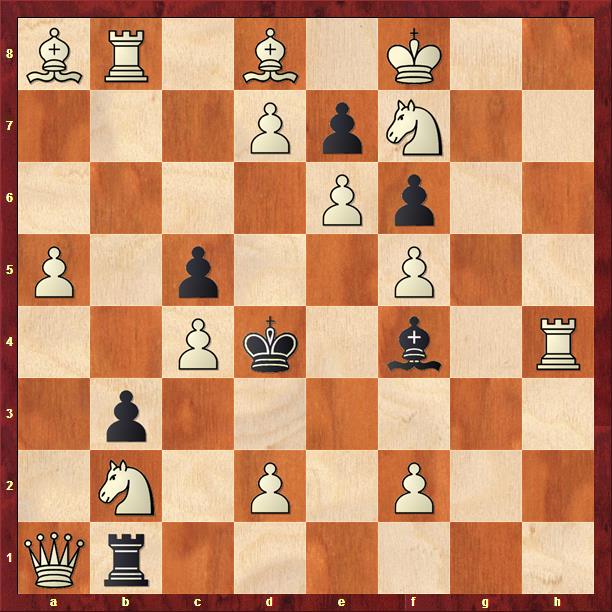

This attacks the queen. If black plays 1. … Qxa7, then after 2. Rxa4 he will quickly be mated. He fares no better with 1. … Qxd8+ 2. Kg7! Qg8+ 3. Kxg8 followed by promoting the d-pawn. As a small taste of some of the by-play, let’s consider 1. … Qe5, maintaining his defense of the bishop:

Now play could continue 2. Bxe7 Qd6 3. Nxd6+ Ke5 4. Nd3 mate:

Very nice! There are other possibilities, but none work out too well for black. So let’s look at more serious tries.

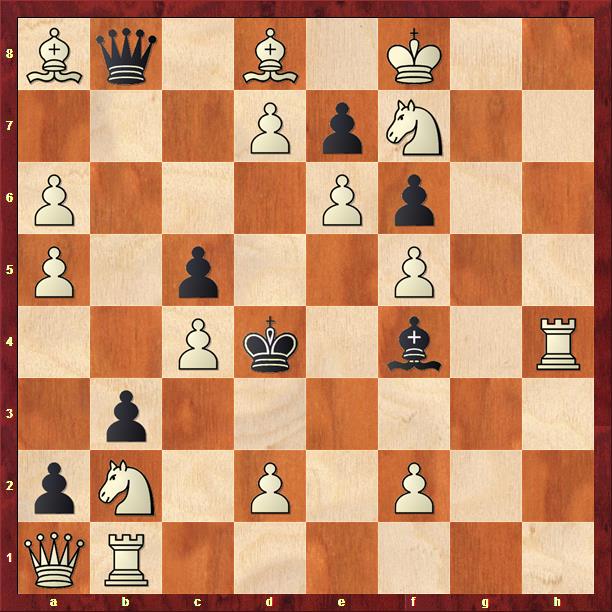

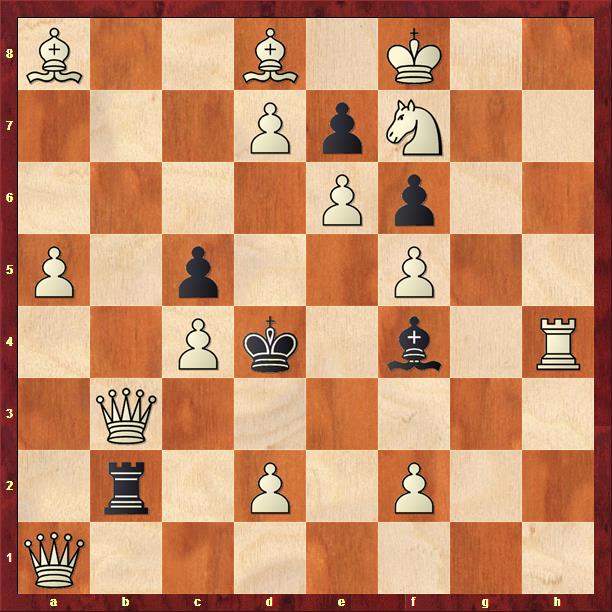

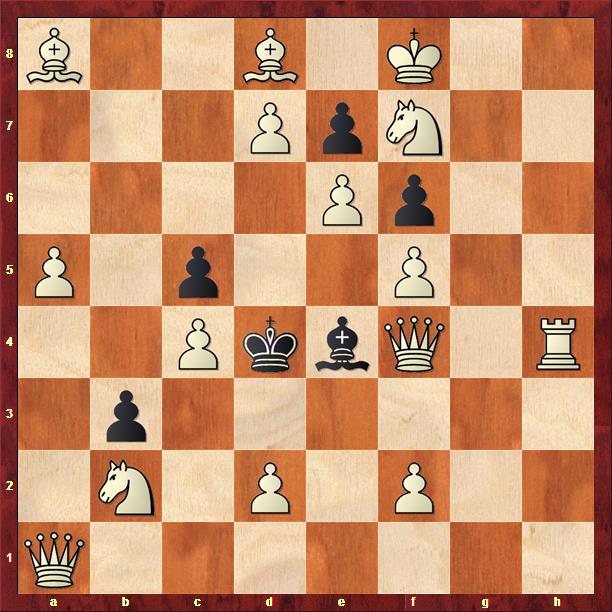

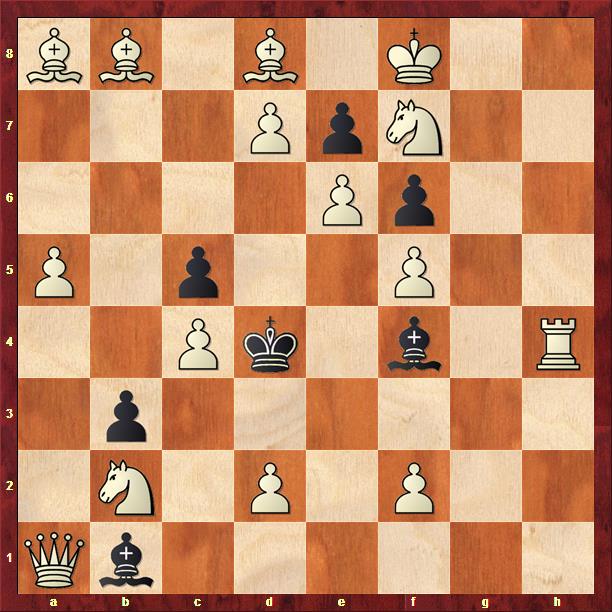

By now you have surely noticed that black’s pawn on a2 could cause some mischief by promoting. So let’s try 1. … axb1=Q. In this case, white must reply with 2. axb8Q, leading to this position:

White attacks f4 a second time, so that after 2. … Qe4 3. Rxf4 he will be able to mate next move. Black also has the defense 2. … Qxb2, which gives the black king flight squares on c4 and d3. But now white plays 3. Qb3, regaining control of both squares. Black is in a bad way, since his queen is pinned. Play might conclude with 3. … Qc3 4. Qaxc3 mate:

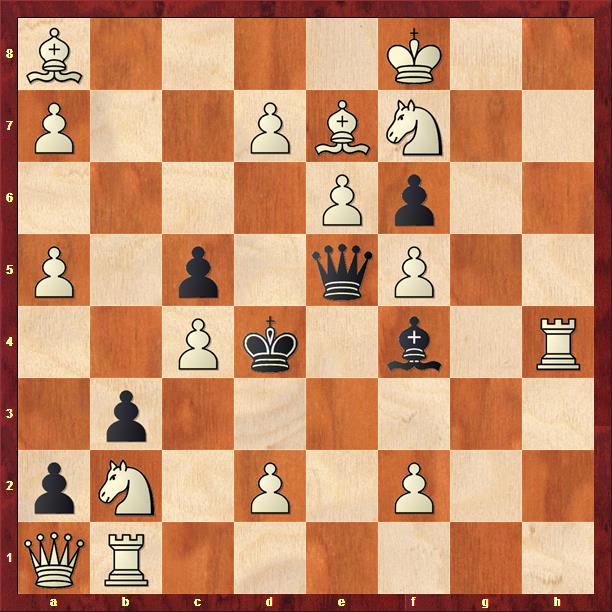

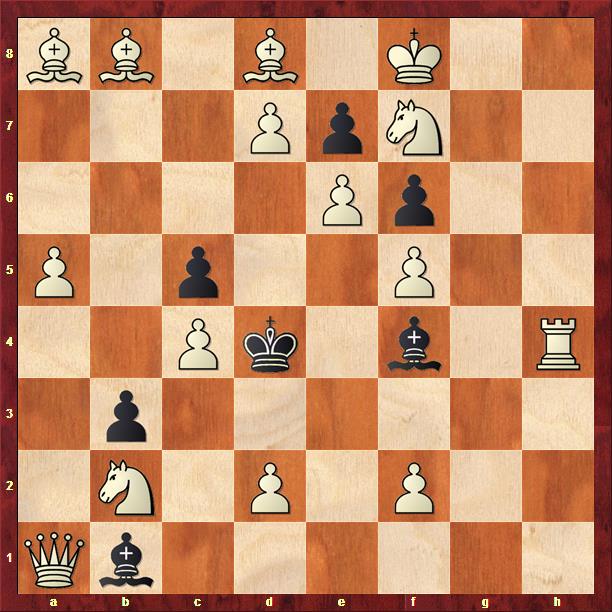

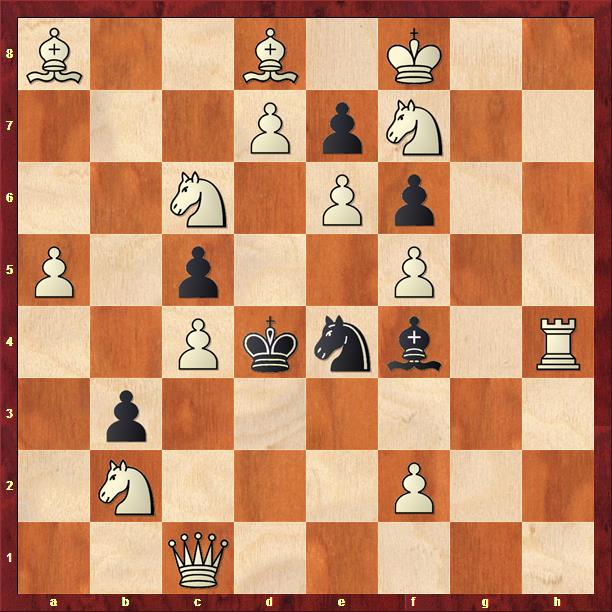

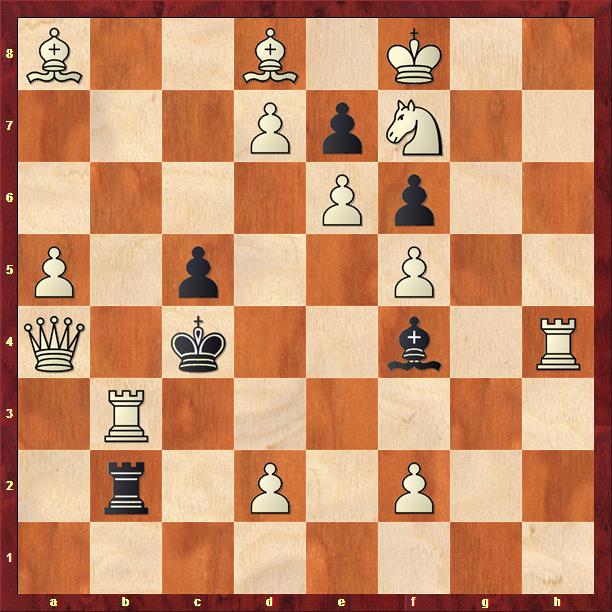

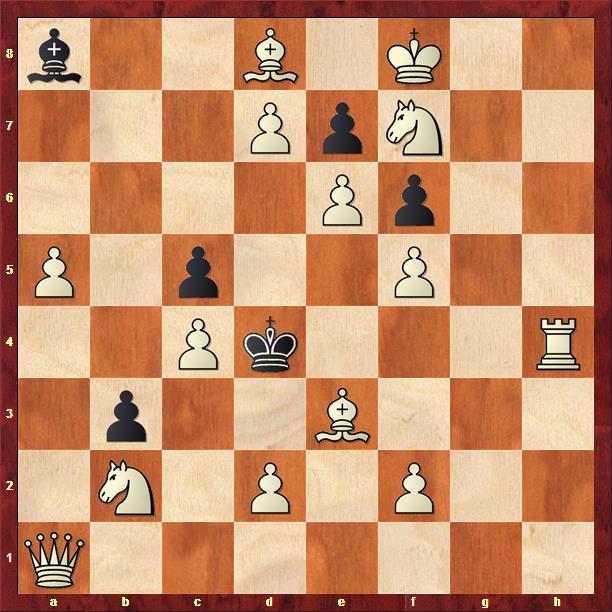

Let’s move on. If black tries 1. … axb1R, then white plays 2. axb8R, leading to this position:

By removing the black queen, white is threatening to take the bishop on f4. Black can defend with 2. … Rxb2, which gives the black king a flight square on d3. White replies with 3. Rb3 which regains control of d3. Black’s only move now is 3. … Kxc4 and play concludes with 4. Qa4 mate:

Lovely! But what would have happened had white promoted to a queen instead of a rook. Well, in that case we would have 2. … Rxb2 3. Qb3:

and black is stalemated! That is why a rook promotion was necessary.

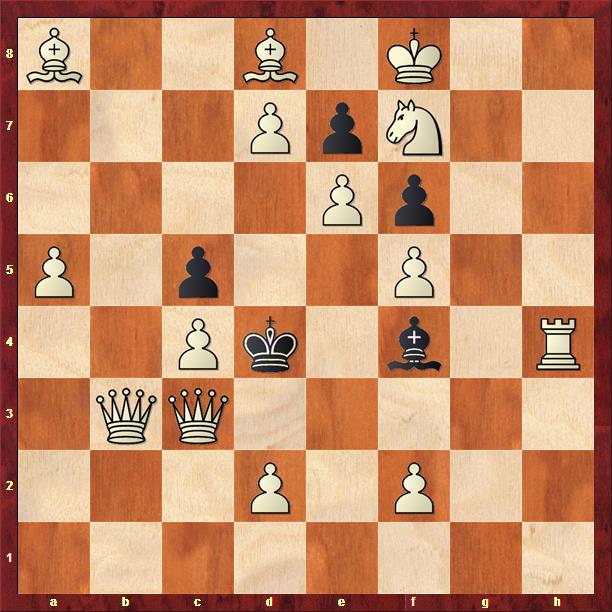

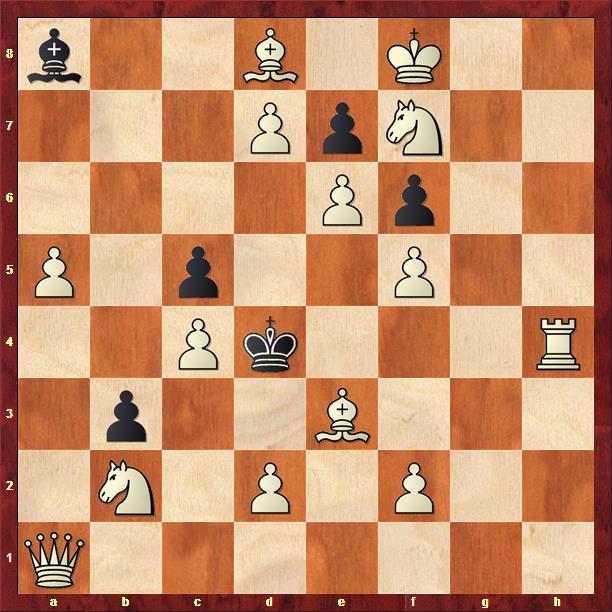

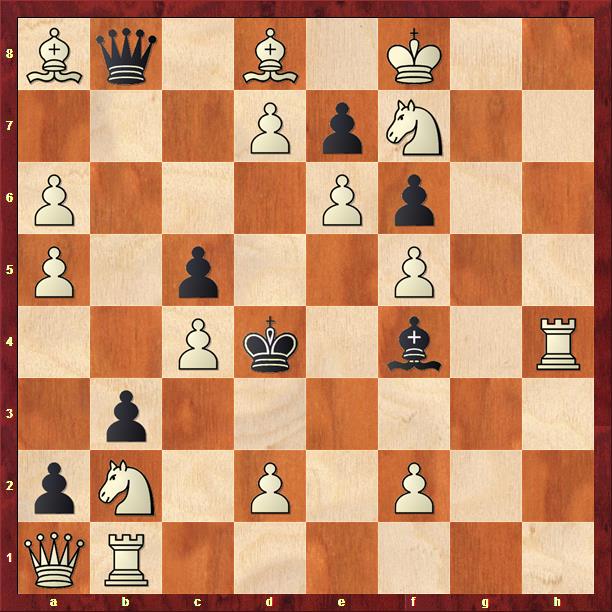

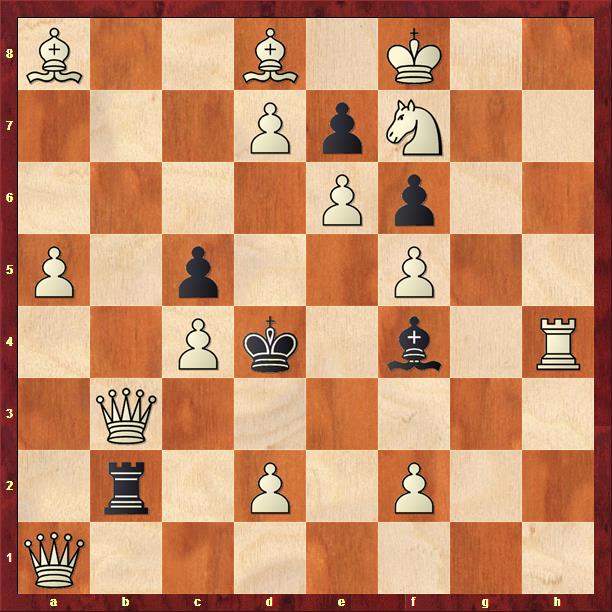

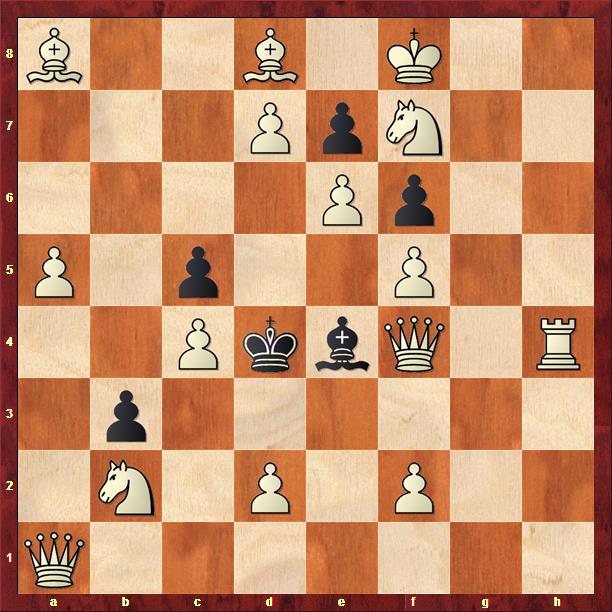

Bishop promotions lead to this position, after 1. … axb1B 2. axb8B:

Black’s promotion gives him an ingenious defense. He can play 2. … Be4. The point is that if white now continues with 3. Rxf4, then black is stalemated once again. Yikes! What should white do?

But now we see the point of white’s bishop promotion. Instead of taking on f4 with the rook, white plays 3. Bxf4. Black must now move his bishop, say 3. … Bxa8, and white mates with 4. Be3 mate:

By now you’ve probably realized why a queen promotion by white would not work. After 2. … Be4 3. Qxf4:

(or 3. Rxf4) black is stalemated. Again.

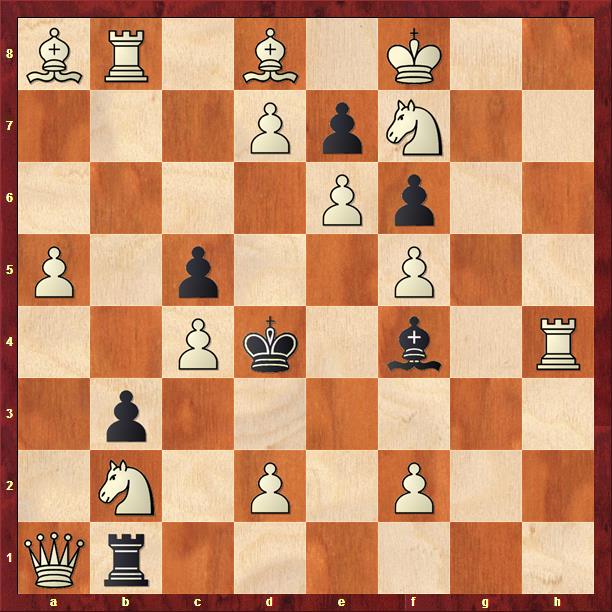

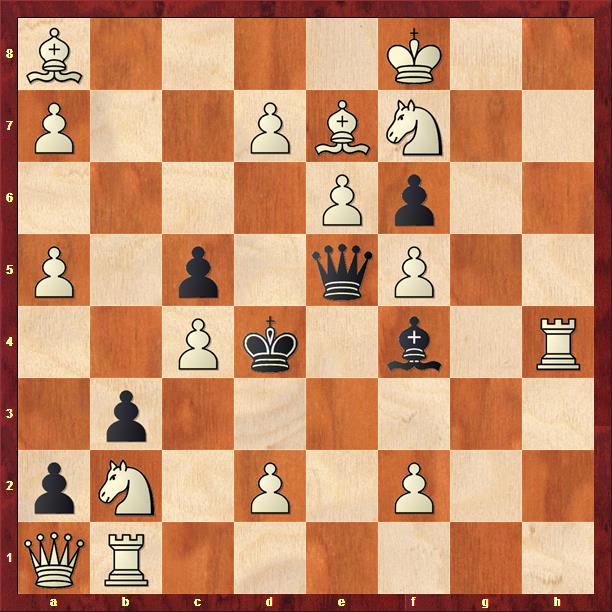

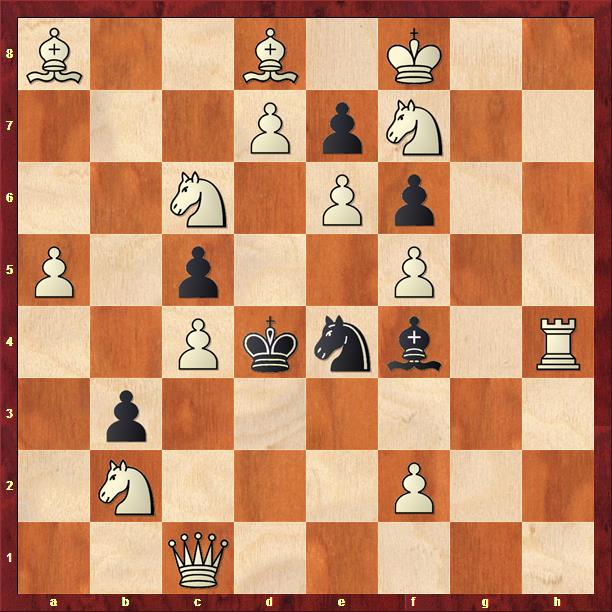

That only leaves the knight promotion. We have 1. … axb1N 2. axb8N:

Black has now acquired the defense 2. … Nxd2. This gives the black king a flight square on c3. White has many powerful moves at his disposal, of course, but if the black king slips away to c3 then he will be able to survive past move four, which is all he needs to do. So white plays 3. Qc1, to regain control of c3.

It is now black’s turn. His only mobile piece is his knight, but a random such as 3. … Nf1 would simply allow 4. Rxf4 mate. So black plays 3. … Ne4. Alas, this now blocks the square e4, and allows white to play 4. Nc6 mate:

It is for this one line that a knight promotion is needed! Notice that the white knight on c6 blocks the white bishop on a8. That would have left e4 unguarded, but for the fact that the black knight is now sitting there.

Just amazing! Even more amazing was that Yarosh was a complete unknown among problem composers, prior to this stunning composition.

See you next week!

from ScienceBlogs http://scienceblogs.com/evolutionblog/2014/12/28/sunday-chess-problem-28/

Well, it’s taken me longer to get back to this than I originally planned, but how about a second look at the Babson Task? The problem below was composed by Leonid Yarosh, in 1983. It’s white to move and mate in four:

Remember that white is always moving up the board and black is always moving down. So, black’s pawn on a2 is poised to promote.

Folks, this is one of the most famous diagrams in the history of chess composition. Why? It’s one of the first direct mates to show the Babson Task, and the first to show the task with an acceptable key. (The absolute first had a key that involved white capturing a black piece, which is a major aesthetic faux pas, even in a problem showing a remarkable task).

We have considered the Babson Task before. The task calls for four variations. In each, the same black pawn promotes to one of the four possible pieces. White must answer each each promotion by promoting a pawn to the same kind of piece. So, if black defends against a threat by promoting to a queen, then white must answer with a queen promotion of his own. If black promotes to a rook, then white must also promote to a rook. Of course, when I say that white must promote to a rook I mean that any other move would not allow him to complete the stipulation.

Now, before moving on to the solution, I want to introduce some problem jargon for you. Typically a problem has a theme, which can be thought of as the main strategic or tactical point the composition was meant to illustrate. Certain variations in the problem contribute to that theme. Often, though, the composer finds it necessary to include other variations whose sole purpose is to make the problem sound. They do not contribute to the theme. Such variations are referred to as by-play. An excessive amount of by-play is usually considered an aesthetic weakness, since it distracts from the theme of the problem. On the other hand, if the by-play is itself tactically interesting it can sometimes enhance a problem.

Anyway, this problem has a ton of by-play. I will ignore nearly all of it. You can check out this discussion if you want to explore more of this problem’s subtleties.

Time to get down to business. If the black queen could be distracted from its defense of the bishop on f4, then white would have a powerful threat in the move Rxf4. This suggests the key move: 1. a7!

This attacks the queen. If black plays 1. … Qxa7, then after 2. Rxa4 he will quickly be mated. He fares no better with 1. … Qxd8+ 2. Kg7! Qg8+ 3. Kxg8 followed by promoting the d-pawn. As a small taste of some of the by-play, let’s consider 1. … Qe5, maintaining his defense of the bishop:

Now play could continue 2. Bxe7 Qd6 3. Nxd6+ Ke5 4. Nd3 mate:

Very nice! There are other possibilities, but none work out too well for black. So let’s look at more serious tries.

By now you have surely noticed that black’s pawn on a2 could cause some mischief by promoting. So let’s try 1. … axb1=Q. In this case, white must reply with 2. axb8Q, leading to this position:

White attacks f4 a second time, so that after 2. … Qe4 3. Rxf4 he will be able to mate next move. Black also has the defense 2. … Qxb2, which gives the black king flight squares on c4 and d3. But now white plays 3. Qb3, regaining control of both squares. Black is in a bad way, since his queen is pinned. Play might conclude with 3. … Qc3 4. Qaxc3 mate:

Let’s move on. If black tries 1. … axb1R, then white plays 2. axb8R, leading to this position:

By removing the black queen, white is threatening to take the bishop on f4. Black can defend with 2. … Rxb2, which gives the black king a flight square on d3. White replies with 3. Rb3 which regains control of d3. Black’s only move now is 3. … Kxc4 and play concludes with 4. Qa4 mate:

Lovely! But what would have happened had white promoted to a queen instead of a rook. Well, in that case we would have 2. … Rxb2 3. Qb3:

and black is stalemated! That is why a rook promotion was necessary.

Bishop promotions lead to this position, after 1. … axb1B 2. axb8B:

Black’s promotion gives him an ingenious defense. He can play 2. … Be4. The point is that if white now continues with 3. Rxf4, then black is stalemated once again. Yikes! What should white do?

But now we see the point of white’s bishop promotion. Instead of taking on f4 with the rook, white plays 3. Bxf4. Black must now move his bishop, say 3. … Bxa8, and white mates with 4. Be3 mate:

By now you’ve probably realized why a queen promotion by white would not work. After 2. … Be4 3. Qxf4:

(or 3. Rxf4) black is stalemated. Again.

That only leaves the knight promotion. We have 1. … axb1N 2. axb8N:

Black has now acquired the defense 2. … Nxd2. This gives the black king a flight square on c3. White has many powerful moves at his disposal, of course, but if the black king slips away to c3 then he will be able to survive past move four, which is all he needs to do. So white plays 3. Qc1, to regain control of c3.

It is now black’s turn. His only mobile piece is his knight, but a random such as 3. … Nf1 would simply allow 4. Rxf4 mate. So black plays 3. … Ne4. Alas, this now blocks the square e4, and allows white to play 4. Nc6 mate:

It is for this one line that a knight promotion is needed! Notice that the white knight on c6 blocks the white bishop on a8. That would have left e4 unguarded, but for the fact that the black knight is now sitting there.

Just amazing! Even more amazing was that Yarosh was a complete unknown among problem composers, prior to this stunning composition.

See you next week!

from ScienceBlogs http://scienceblogs.com/evolutionblog/2014/12/28/sunday-chess-problem-28/

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire