View larger. | In 2014, as the Quadrantids were flying, people at far northern latitudes were seeing auroras. Photo by Tommy Eliassen.

The Quadrantid meteor shower is 2020’s first major meteor shower. We’ll have moon-free skies during the predawn hours on January 4 for this year’s peak, expected late night January 3 until dawn January 4. Although the Quadrantids have been known to produce some 50-100 meteors in a dark sky, their peak is extremely narrow, time-wise. Peaks of the Perseid or Geminid meteor showers persist for a day or more, allowing all time zones around the world to enjoy a good display of Perseids or Geminids. But the Quadrantids’ peak lasts only a few hours. So you have to be on the right part of Earth – preferably with the radiant high in your sky – in order to experience the peak of the Quadrantids. What’s more, the shower favors the Northern Hemisphere because its radiant point is so far north on the sky’s dome.

So you need some luck to see the Quadrantids, and being in the Northern Hemisphere does help. Who will see the 2020 shower? Keep in mind the prediction of the Quadrantid peak represents an educated guess, not an ironclad guarantee.

That said, in 2020 the International Meteor Organization gives the peak as January 4 at 08:00 UTC. If that prediction of the peak holds true, North America has a good shot at viewing the shower at its best during the predawn hours on January 4.

Just know that meteor showers are notorious for defying the best-laid forecasts. Thus for the Quadrantids – as for any meteor shower – your best plan is simply to look for yourself.

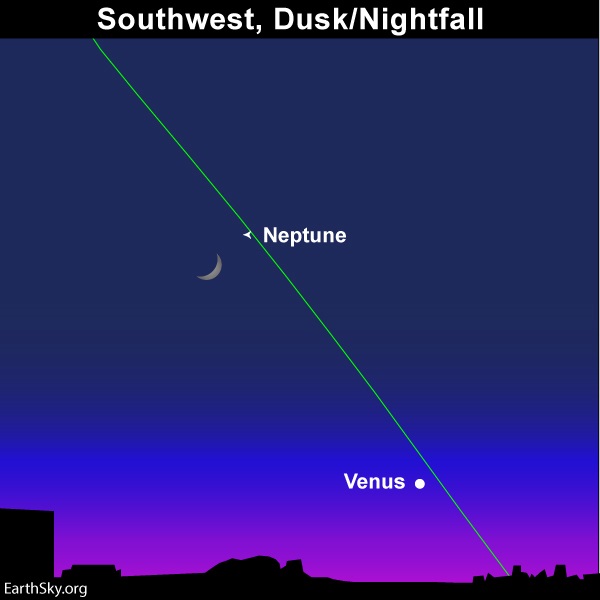

Any place at mid-northern and far-northern latitudes might be in a decent position to watch the Quadrantids in 2020, especially as there is no moonlight in the predawn hours to ruin this year’s show.

All other things being equal, for any meteor shower, you are likely to see the most meteors when the radiant is high in the sky.

In the case of the Quadrantid shower, the radiant point is seen highest in the sky in the dark hours before dawn.

From mid-northern latitudes, the radiant point for the Quadrantid shower doesn’t climb over the horizon until after midnight.

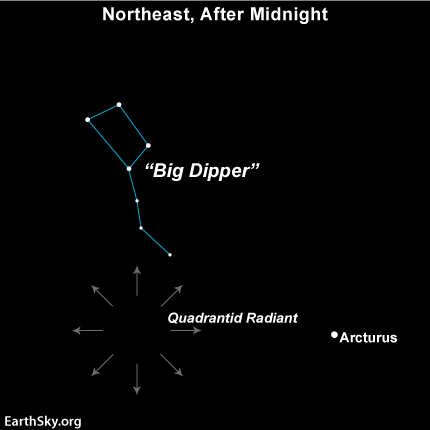

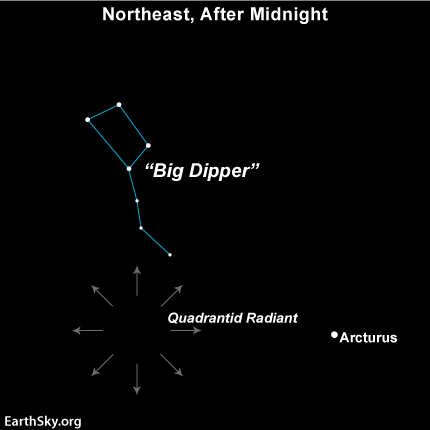

Where is the Quadrantids’ radiant point?

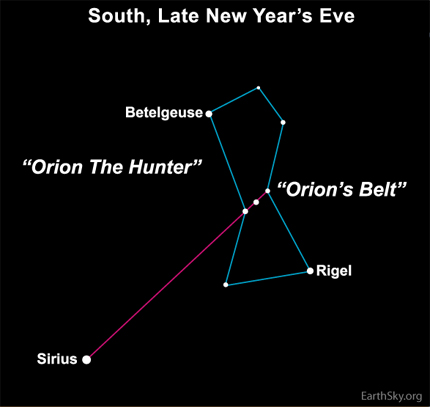

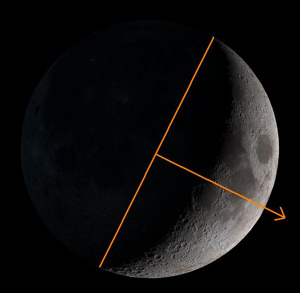

The radiant point of the Quadrantid shower makes an approximate right angle with the Big Dipper and the bright star Arcturus. If you trace the paths of the Quadrantid meteors backward, they appear to radiate from this point on the starry sky.

Now for our usual caveat. You don’t need to find the meteor shower radiant to see the Quadrantid meteors.

You just have to be at mid-northern or far-northern latitudes, up in the wee hours of the morning and hope the peak comes at just the right time to your part of the world.

The meteors will radiate from the northern sky, but appear in all parts of the sky.

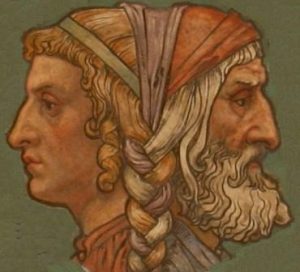

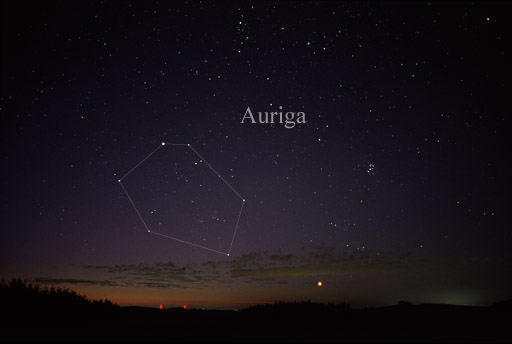

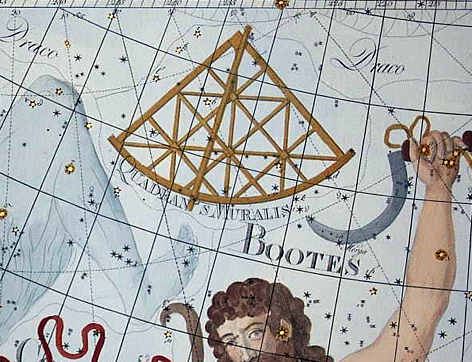

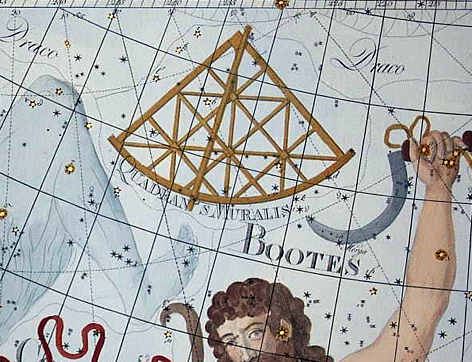

The now-defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis, for which the Quadrantids are named. Image via Atlas Coelestis.

The Quadrantids are named for a constellation that no longer exists. Most meteor showers are named for the constellations from which they appear to radiate. So it is with the Quadrantids. But the Quadrantids’ constellation no longer exists, except in memory. The name Quadrantids comes from the constellation Quadrans Muralis (Mural Quadrant), created by the French astronomer Jerome Lalande in 1795. This now-obsolete constellation was located between the constellations of Bootes the Herdsman and Draco the Dragon. Where did it go?

To understand the history of the Quadrantids’ name, we have to go back to the earliest observations of this shower. In early January 1825, Antonio Brucalassi in Italy reported that:

… the atmosphere was traversed by a multitude of the luminous bodies known by the name of falling stars.

They appeared to radiate from Quadrans Muralis. In 1839, Adolphe Quetelet of Brussels Observatory in Belgium and Edward C. Herrick in Connecticut independently made the suggestion that the Quadrantids are an annual shower.

But in 1922 the International Astronomical Union devised a list 88 modern constellations. The list was agreed upon by the International Astronomical Union at its inaugural General Assembly held in Rome in May 1922. It did not include a constellation Quadrans Muralis.

Today, this meteor shower retains the name Quadrantids, for the original and now obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis.

The radiant point for the Quadrantids is now considered to be at the northern tip of Bootes, near the Big Dipper asterism in our sky, not far from Bootes’ brightest star Arcturus. It is very far north on the sky’s dome, which is why Southern Hemisphere observers probably won’t see many (if any) Quadrantid meteors. Most of the meteors simply won’t make it above the horizon for Southern Hemisphere skywatchers. But some might!

In 2003, Peter Jenniskens proposed that this object, 2003 EH1, is the parent body of the Quadrantid meteor shower.

Quadrantid meteors have a mysterious parent object. In 2003, astronomer Peter Jenniskens tentatively identified the parent body of the Quadrantids as the asteroid 2003 EH1. If indeed this body is the Quadrantids’ parent, then the Quadrantids, like the Geminid meteors, come from a rocky body – not an icy comet. Strange.

In turn, though, 2003 EH1 might be the same object as the comet C/1490 Y1, which was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Korean astronomers 500 years ago.

So the exact story behind the Quadrantids’ parent object remains somewhat mysterious.

Bottom line: The first major meteor shower of 2020, and every year, the Quadrantid meteor shower will probably be at its best in the hours between 2 a.m. and dawn January 4. Fortunately, in 2020, the absence of moonlight in the predawn sky means dark skies during the peak hours of this year’s annual Quadrantid meteor shower.

Best New Year’s gift ever! EarthSky moon calendar for 2019

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/35kiLUI

View larger. | In 2014, as the Quadrantids were flying, people at far northern latitudes were seeing auroras. Photo by Tommy Eliassen.

The Quadrantid meteor shower is 2020’s first major meteor shower. We’ll have moon-free skies during the predawn hours on January 4 for this year’s peak, expected late night January 3 until dawn January 4. Although the Quadrantids have been known to produce some 50-100 meteors in a dark sky, their peak is extremely narrow, time-wise. Peaks of the Perseid or Geminid meteor showers persist for a day or more, allowing all time zones around the world to enjoy a good display of Perseids or Geminids. But the Quadrantids’ peak lasts only a few hours. So you have to be on the right part of Earth – preferably with the radiant high in your sky – in order to experience the peak of the Quadrantids. What’s more, the shower favors the Northern Hemisphere because its radiant point is so far north on the sky’s dome.

So you need some luck to see the Quadrantids, and being in the Northern Hemisphere does help. Who will see the 2020 shower? Keep in mind the prediction of the Quadrantid peak represents an educated guess, not an ironclad guarantee.

That said, in 2020 the International Meteor Organization gives the peak as January 4 at 08:00 UTC. If that prediction of the peak holds true, North America has a good shot at viewing the shower at its best during the predawn hours on January 4.

Just know that meteor showers are notorious for defying the best-laid forecasts. Thus for the Quadrantids – as for any meteor shower – your best plan is simply to look for yourself.

Any place at mid-northern and far-northern latitudes might be in a decent position to watch the Quadrantids in 2020, especially as there is no moonlight in the predawn hours to ruin this year’s show.

All other things being equal, for any meteor shower, you are likely to see the most meteors when the radiant is high in the sky.

In the case of the Quadrantid shower, the radiant point is seen highest in the sky in the dark hours before dawn.

From mid-northern latitudes, the radiant point for the Quadrantid shower doesn’t climb over the horizon until after midnight.

Where is the Quadrantids’ radiant point?

The radiant point of the Quadrantid shower makes an approximate right angle with the Big Dipper and the bright star Arcturus. If you trace the paths of the Quadrantid meteors backward, they appear to radiate from this point on the starry sky.

Now for our usual caveat. You don’t need to find the meteor shower radiant to see the Quadrantid meteors.

You just have to be at mid-northern or far-northern latitudes, up in the wee hours of the morning and hope the peak comes at just the right time to your part of the world.

The meteors will radiate from the northern sky, but appear in all parts of the sky.

The now-defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis, for which the Quadrantids are named. Image via Atlas Coelestis.

The Quadrantids are named for a constellation that no longer exists. Most meteor showers are named for the constellations from which they appear to radiate. So it is with the Quadrantids. But the Quadrantids’ constellation no longer exists, except in memory. The name Quadrantids comes from the constellation Quadrans Muralis (Mural Quadrant), created by the French astronomer Jerome Lalande in 1795. This now-obsolete constellation was located between the constellations of Bootes the Herdsman and Draco the Dragon. Where did it go?

To understand the history of the Quadrantids’ name, we have to go back to the earliest observations of this shower. In early January 1825, Antonio Brucalassi in Italy reported that:

… the atmosphere was traversed by a multitude of the luminous bodies known by the name of falling stars.

They appeared to radiate from Quadrans Muralis. In 1839, Adolphe Quetelet of Brussels Observatory in Belgium and Edward C. Herrick in Connecticut independently made the suggestion that the Quadrantids are an annual shower.

But in 1922 the International Astronomical Union devised a list 88 modern constellations. The list was agreed upon by the International Astronomical Union at its inaugural General Assembly held in Rome in May 1922. It did not include a constellation Quadrans Muralis.

Today, this meteor shower retains the name Quadrantids, for the original and now obsolete constellation Quadrans Muralis.

The radiant point for the Quadrantids is now considered to be at the northern tip of Bootes, near the Big Dipper asterism in our sky, not far from Bootes’ brightest star Arcturus. It is very far north on the sky’s dome, which is why Southern Hemisphere observers probably won’t see many (if any) Quadrantid meteors. Most of the meteors simply won’t make it above the horizon for Southern Hemisphere skywatchers. But some might!

In 2003, Peter Jenniskens proposed that this object, 2003 EH1, is the parent body of the Quadrantid meteor shower.

Quadrantid meteors have a mysterious parent object. In 2003, astronomer Peter Jenniskens tentatively identified the parent body of the Quadrantids as the asteroid 2003 EH1. If indeed this body is the Quadrantids’ parent, then the Quadrantids, like the Geminid meteors, come from a rocky body – not an icy comet. Strange.

In turn, though, 2003 EH1 might be the same object as the comet C/1490 Y1, which was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Korean astronomers 500 years ago.

So the exact story behind the Quadrantids’ parent object remains somewhat mysterious.

Bottom line: The first major meteor shower of 2020, and every year, the Quadrantid meteor shower will probably be at its best in the hours between 2 a.m. and dawn January 4. Fortunately, in 2020, the absence of moonlight in the predawn sky means dark skies during the peak hours of this year’s annual Quadrantid meteor shower.

Best New Year’s gift ever! EarthSky moon calendar for 2019

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/35kiLUI