Goodbye 2018, and hello 2019! Singapore celebrates the New Year with spectacular fireworks. Image via Channel NewsAsia.

The date of a new year isn’t precisely fixed by any natural or seasonal marker. Instead, our celebration of New Year’s Day on January 1 is a civil event. That’s despite the fact that, for us in the Northern Hemisphere – where daylight has ebbed to its lowest point and the days are getting longer again – there’s a feeling of rebirth in the air.

Our modern celebration of New Year’s Day stems from an ancient Roman custom, the feast of the Roman god Janus: god of doorways and beginnings. The name for the month of January also comes from Janus, who was depicted as having two faces. One face of Janus looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future.

To celebrate the new year, the Romans made promises to Janus. From this ancient practice comes our tradition of making New Year’s Day resolutions.

Best New Year’s gift ever! EarthSky moon calendar for 2020. Almost sold out.

Janus the doorkeeper via tablesbeyondbelief.

January 1 hasn’t been New Year’s Day throughout history, though. In the past, some New Year’s celebrations took place at an equinox, a day when the sun is above Earth’s equator, and night and day are equal in length. In many cultures, the March or vernal equinox marks a time of transition and new beginnings, and so cultural celebrations of a new year were natural for that equinox. The September or autumnal equinox also had its proponents for the beginning of a new year. For example, the French Republican Calendar – implemented during the French Revolution and used for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805 – started its year at the September equinox.

The Greeks celebrated the new year on the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year.

Today, although many do celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1, some cultures and religions do not. Jews use a lunar calendar and celebrate the New Year on Rosh Hashanah, the first day of the month of Tishri, which is the first month of the Jewish calendar. This date usually occurs in September.

Most are also familiar with the Chinese New Year, celebrated for weeks in January or early February. In 2020, the Chinese Year of the Rat begins on January 25.

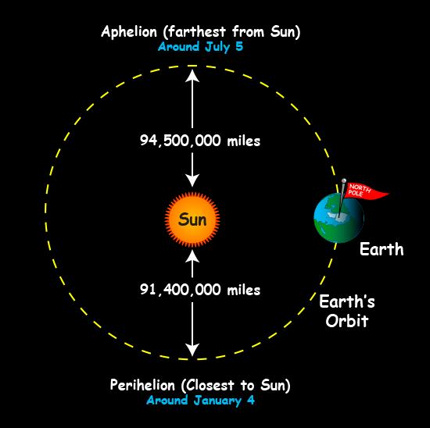

By the way, in addition to the longer days here in the Northern Hemisphere, there’s another astronomical occurrence around January 1 each year that’s also related to Earth’s year, as defined by our orbit around the sun. That is, Earth’s perihelion – or closest point to the sun – happens every year in early January. In 2020, perihelion comes on January 4-5.

We don’t celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 for this reason, but it would make sense if we did. Perihelion – our closest point to the sun in our yearly orbit – takes place each year in early January. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: The reason to celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 is historical, not astronomical. The New Year was celebrated according to astronomical events – such as equinoxes and solstices – eons ago. Our modern New Year’s celebration stems from the ancient, two-faced Roman god Janus, after whom the month of January is also named. One face of Janus looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/35glNci

Goodbye 2018, and hello 2019! Singapore celebrates the New Year with spectacular fireworks. Image via Channel NewsAsia.

The date of a new year isn’t precisely fixed by any natural or seasonal marker. Instead, our celebration of New Year’s Day on January 1 is a civil event. That’s despite the fact that, for us in the Northern Hemisphere – where daylight has ebbed to its lowest point and the days are getting longer again – there’s a feeling of rebirth in the air.

Our modern celebration of New Year’s Day stems from an ancient Roman custom, the feast of the Roman god Janus: god of doorways and beginnings. The name for the month of January also comes from Janus, who was depicted as having two faces. One face of Janus looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future.

To celebrate the new year, the Romans made promises to Janus. From this ancient practice comes our tradition of making New Year’s Day resolutions.

Best New Year’s gift ever! EarthSky moon calendar for 2020. Almost sold out.

Janus the doorkeeper via tablesbeyondbelief.

January 1 hasn’t been New Year’s Day throughout history, though. In the past, some New Year’s celebrations took place at an equinox, a day when the sun is above Earth’s equator, and night and day are equal in length. In many cultures, the March or vernal equinox marks a time of transition and new beginnings, and so cultural celebrations of a new year were natural for that equinox. The September or autumnal equinox also had its proponents for the beginning of a new year. For example, the French Republican Calendar – implemented during the French Revolution and used for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805 – started its year at the September equinox.

The Greeks celebrated the new year on the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year.

Today, although many do celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1, some cultures and religions do not. Jews use a lunar calendar and celebrate the New Year on Rosh Hashanah, the first day of the month of Tishri, which is the first month of the Jewish calendar. This date usually occurs in September.

Most are also familiar with the Chinese New Year, celebrated for weeks in January or early February. In 2020, the Chinese Year of the Rat begins on January 25.

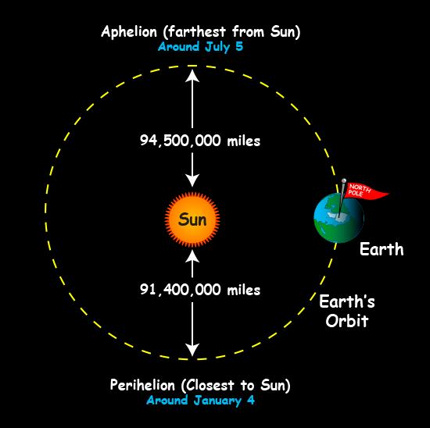

By the way, in addition to the longer days here in the Northern Hemisphere, there’s another astronomical occurrence around January 1 each year that’s also related to Earth’s year, as defined by our orbit around the sun. That is, Earth’s perihelion – or closest point to the sun – happens every year in early January. In 2020, perihelion comes on January 4-5.

We don’t celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 for this reason, but it would make sense if we did. Perihelion – our closest point to the sun in our yearly orbit – takes place each year in early January. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: The reason to celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1 is historical, not astronomical. The New Year was celebrated according to astronomical events – such as equinoxes and solstices – eons ago. Our modern New Year’s celebration stems from the ancient, two-faced Roman god Janus, after whom the month of January is also named. One face of Janus looked back into the past, and the other peered forward to the future.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/35glNci

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire