Artist’s concept of the collision between 2 asteroids – some 460 million years ago – that created enough dust to cause an ice age on Earth. Image via Don Davis/Southwest Research Institute/EurekAlert.

Some 460 million years ago, Earth was a frozen world, caught in the grip of a global ice age. For a long time, scientists have been trying to figure what caused this ice age, which occurred in what they call the Ordovician period, and which coincided with a major mass extinction of nearly 61% of marine life. Now they think they may finally know. A new study – announced on September 18, 2019, by the Field Museum in Chicago – suggests the ice age resulted from a collision between two asteroids, not onto Earth, but with each other, in outer space. The collision may have caused much more dust than usual to enter Earth’s atmosphere. The influx of dust may have caused a global cooling that turned Earth into a colder, icier world.

These peer-reviewed results were published on September 18 in the journal Science Advances.

Philipp Heck is one of the paper’s authors and a curator at the Field Museum. He explained in a statement:

Normally, Earth gains about 40,000 tons of extraterrestrial material every year. Imagine multiplying that by a factor of a thousand or ten thousand. Our hypothesis is that the large amounts of extraterrestrial dust over a timeframe of at least two million years played an important role in changing the climate on Earth, contributing to cooling.

Lead author of the research, Birger Schmitz, also at the Field Museum, added:

Our results show for the first time that such dust, at times, has cooled Earth dramatically. Our studies can give a more detailed, empirical-based understanding of how this works, and this in turn can be used to evaluate if model simulations are realistic.

The mid-Ordovician Hällekis section in sedimentary rock in southern Sweden, where the dust samples were found. The time of the asteroid collision/dust impact is represented by the red line. Image via Birger Schmitz/Lund University/Science Advances.

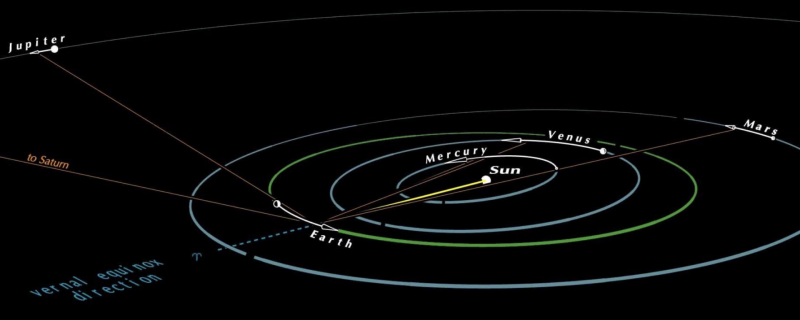

According to these scientists, the greatly increased amount of dust entering Earth’s atmosphere upset the climate balance enough to cause a new ice age, even if it took a couple million years to do it. In the collision, the study concludes, a 93-mile-wide asteroid broke apart somewhere between Mars and Jupiter. That was still close enough for much more dust then normal to enter Earth’s atmosphere.

It’s a fascinating hypothesis, but how did the scientists reach this conclusion?

They looked at samples from a place on Earth that is still pretty much frozen year-round: Antarctica. Micrometeorites from Antarctica, which are common, were compared to other 466-million-year-old rocks from sedimentary layers – the mid-Ordovician Hällekis section – in southern Sweden. According to Heck:

We studied extraterrestrial matter, meteorites and micrometeorites, in the sedimentary record of Earth, meaning rocks that were once sea floor. And then we extracted the extraterrestrial matter to discover what it was and where it came from.

A 466-million-year-old fossil meteorite, thought to have been created in the same asteroid collision that caused enough dust to create an ice age. The fossil of a squid-like creature called a nautiloid can also be seen along the top. Image via Field Museum/John Weinstein/EurekAlert.

In order to retrieve the space dust from the rocks, the research team used special acid to erode the rock and leave behind the dust particles, which were then analyzed. Then, rock samples from the ancient sea floor were also examined; the scientists wanted to find elements and isotopes that they could identify as having originated from space. As an example, helium atoms on Earth have two protons, two neutrons and two electrons. But, helium atoms that come from the sun are missing one neutron. Since those kinds of helium atoms, as well as traces of rare metals found in asteroids, were found in the 466-million-year-old rocks, that showed that the dust came from space.

It was already known that there was an ice age at this time, and the new study shows that the timing of it coincided with the extra dust in the atmosphere. As Schmitz said:

The timing appears to be perfect.

The researchers also found other evidence that some of Earth’s water at the time was trapped in glaciers and sea ice, since the analysis of the rocks indicated that the oceans were shallower at this time. All of this together is evidence that the increased dust in the atmosphere created a global cooling and ultimately an ice age.

A chromite grain (light gray) from a micrometeorite in Antarctica. The grain was not included in the present study but is used here to illustrate the distribution of such relict grains in micrometeorites. Image via ScienceAdvances.

It’s a good thing that the cooling process was gradual, as that allowed much of earthly life to adapt to the changing conditions. According to Heck:

In the global cooling we studied, we’re talking about timescales of millions of years. It’s very different from the climate change caused by the meteorite 65 million years ago that killed the dinosaurs, and it’s different from the global warming today – this global cooling was a gentle nudge. There was less stress.

The researchers also noted that it might be tempting to think that dust like this might be a good way to combat climate change. But Heck urges caution even though it’s an idea worth studying:

Geoengineering proposals should be evaluated very critically and very carefully, because if something goes wrong, things could become worse than before. We’re experiencing global warming, it’s undeniable. And we need to think about how we can prevent catastrophic consequences, or minimize them. Any idea that’s reasonable should be explored.

The results of this study provide valuable insight into how a global ice age started millions of years ago – from an asteroid collision in deep space – and may even assist scientists in determining ways to mitigate current climate change.

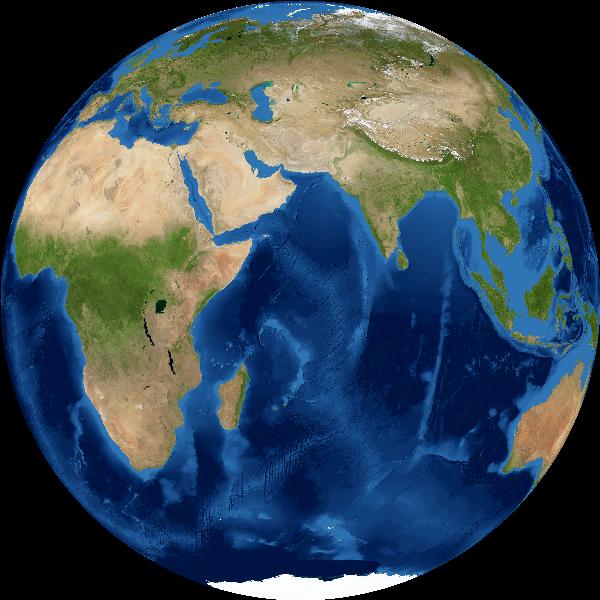

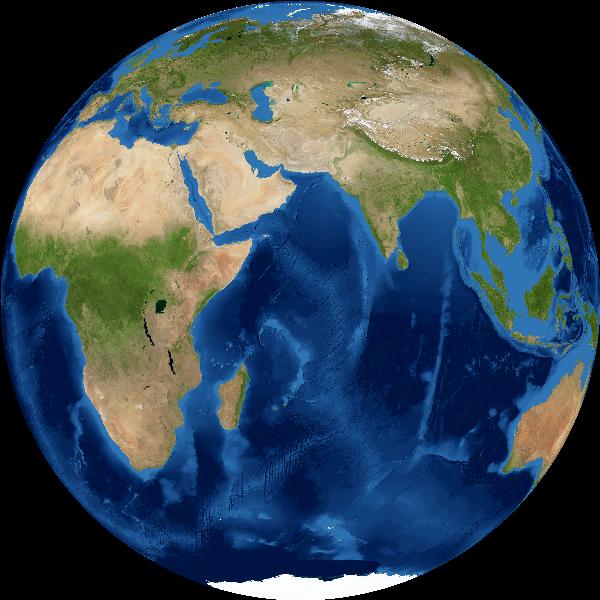

Some 460 million years ago, Earth was in the grip of a global ice age like the one in this artist’s concept. The new study suggests it was caused by dust from a collision between 2 asteroids. Image via NASA/Gizmodo.

Bottom line: A global ice age 466 million years ago was caused by dust from a collision between two asteroids, a new study suggests.

Source: An extraterrestrial trigger for the mid-Ordovician ice age: Dust from the breakup of the L-chondrite parent body

Via Field Museum

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/30q0sLa

Artist’s concept of the collision between 2 asteroids – some 460 million years ago – that created enough dust to cause an ice age on Earth. Image via Don Davis/Southwest Research Institute/EurekAlert.

Some 460 million years ago, Earth was a frozen world, caught in the grip of a global ice age. For a long time, scientists have been trying to figure what caused this ice age, which occurred in what they call the Ordovician period, and which coincided with a major mass extinction of nearly 61% of marine life. Now they think they may finally know. A new study – announced on September 18, 2019, by the Field Museum in Chicago – suggests the ice age resulted from a collision between two asteroids, not onto Earth, but with each other, in outer space. The collision may have caused much more dust than usual to enter Earth’s atmosphere. The influx of dust may have caused a global cooling that turned Earth into a colder, icier world.

These peer-reviewed results were published on September 18 in the journal Science Advances.

Philipp Heck is one of the paper’s authors and a curator at the Field Museum. He explained in a statement:

Normally, Earth gains about 40,000 tons of extraterrestrial material every year. Imagine multiplying that by a factor of a thousand or ten thousand. Our hypothesis is that the large amounts of extraterrestrial dust over a timeframe of at least two million years played an important role in changing the climate on Earth, contributing to cooling.

Lead author of the research, Birger Schmitz, also at the Field Museum, added:

Our results show for the first time that such dust, at times, has cooled Earth dramatically. Our studies can give a more detailed, empirical-based understanding of how this works, and this in turn can be used to evaluate if model simulations are realistic.

The mid-Ordovician Hällekis section in sedimentary rock in southern Sweden, where the dust samples were found. The time of the asteroid collision/dust impact is represented by the red line. Image via Birger Schmitz/Lund University/Science Advances.

According to these scientists, the greatly increased amount of dust entering Earth’s atmosphere upset the climate balance enough to cause a new ice age, even if it took a couple million years to do it. In the collision, the study concludes, a 93-mile-wide asteroid broke apart somewhere between Mars and Jupiter. That was still close enough for much more dust then normal to enter Earth’s atmosphere.

It’s a fascinating hypothesis, but how did the scientists reach this conclusion?

They looked at samples from a place on Earth that is still pretty much frozen year-round: Antarctica. Micrometeorites from Antarctica, which are common, were compared to other 466-million-year-old rocks from sedimentary layers – the mid-Ordovician Hällekis section – in southern Sweden. According to Heck:

We studied extraterrestrial matter, meteorites and micrometeorites, in the sedimentary record of Earth, meaning rocks that were once sea floor. And then we extracted the extraterrestrial matter to discover what it was and where it came from.

A 466-million-year-old fossil meteorite, thought to have been created in the same asteroid collision that caused enough dust to create an ice age. The fossil of a squid-like creature called a nautiloid can also be seen along the top. Image via Field Museum/John Weinstein/EurekAlert.

In order to retrieve the space dust from the rocks, the research team used special acid to erode the rock and leave behind the dust particles, which were then analyzed. Then, rock samples from the ancient sea floor were also examined; the scientists wanted to find elements and isotopes that they could identify as having originated from space. As an example, helium atoms on Earth have two protons, two neutrons and two electrons. But, helium atoms that come from the sun are missing one neutron. Since those kinds of helium atoms, as well as traces of rare metals found in asteroids, were found in the 466-million-year-old rocks, that showed that the dust came from space.

It was already known that there was an ice age at this time, and the new study shows that the timing of it coincided with the extra dust in the atmosphere. As Schmitz said:

The timing appears to be perfect.

The researchers also found other evidence that some of Earth’s water at the time was trapped in glaciers and sea ice, since the analysis of the rocks indicated that the oceans were shallower at this time. All of this together is evidence that the increased dust in the atmosphere created a global cooling and ultimately an ice age.

A chromite grain (light gray) from a micrometeorite in Antarctica. The grain was not included in the present study but is used here to illustrate the distribution of such relict grains in micrometeorites. Image via ScienceAdvances.

It’s a good thing that the cooling process was gradual, as that allowed much of earthly life to adapt to the changing conditions. According to Heck:

In the global cooling we studied, we’re talking about timescales of millions of years. It’s very different from the climate change caused by the meteorite 65 million years ago that killed the dinosaurs, and it’s different from the global warming today – this global cooling was a gentle nudge. There was less stress.

The researchers also noted that it might be tempting to think that dust like this might be a good way to combat climate change. But Heck urges caution even though it’s an idea worth studying:

Geoengineering proposals should be evaluated very critically and very carefully, because if something goes wrong, things could become worse than before. We’re experiencing global warming, it’s undeniable. And we need to think about how we can prevent catastrophic consequences, or minimize them. Any idea that’s reasonable should be explored.

The results of this study provide valuable insight into how a global ice age started millions of years ago – from an asteroid collision in deep space – and may even assist scientists in determining ways to mitigate current climate change.

Some 460 million years ago, Earth was in the grip of a global ice age like the one in this artist’s concept. The new study suggests it was caused by dust from a collision between 2 asteroids. Image via NASA/Gizmodo.

Bottom line: A global ice age 466 million years ago was caused by dust from a collision between two asteroids, a new study suggests.

Source: An extraterrestrial trigger for the mid-Ordovician ice age: Dust from the breakup of the L-chondrite parent body

Via Field Museum

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/30q0sLa