The bright red star Antares, middle, near the prominent star cluster M4, upper right. Photo via Fred Espenak at AstroPixels. Used with permission.

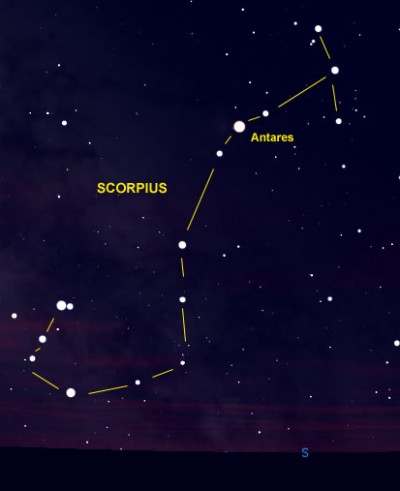

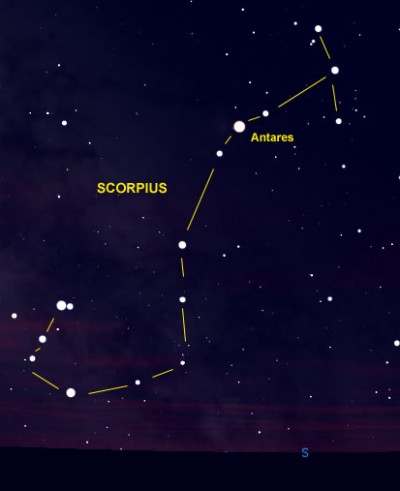

Bright reddish Antares – also known as Alpha Scorpii – is easy to spot on a summer night. It is the brightest star – and distinctly reddish in color – in the fishhook-shaped pattern of stars known as the constellation Scorpius the Scorpion.

Scorpius is one of the few constellations that looks like its namesake. The bright red star Antares marks the Scorpion’s Heart. Notice also the two stars at the tip of the Scorpion’s Tail. They are known as The Stinger.

How to see Antares. If you look southward in early evening from late spring to early fall, you’re likely to notice the fishhook pattern of Scorpius the Scorpion, with ruby Antares at its heart. If you think you’ve found Antares, aim binoculars in its direction. You should notice its reddish color. And you should see a little star cluster – known as M4 – just to the right of this star. (See images above)

Antares is the 16th brightest star in the sky, and it is located in the southern half of Earth’s sky. So your chance of seeing this star on any given night increases as you go farther southward on Earth’s globe. If you traveled to the Southern Hemisphere – from about 67 degrees south latitude – you’d find that Antares is circumpolar, meaning that it never sets and is visible every night of the year from Earth’s southernmost regions.

We in the Northern Hemisphere know Antares better than several other southern stars that are brighter. That’s because Antares is visible from throughout most of the Northern Hemisphere, short of the Arctic. Well, not quite the Arctic, but anywhere south of 63 degrees north latitude can – at one time or another – see Antares. (Helsinki yes, Fairbanks, no)

The midnight culmination of Antares is on or near June 1. That is when Antares is highest in the sky at midnight (midway between sunset and sunrise). It is highest in the sky at about dawn in early March and at about sunset in early September.

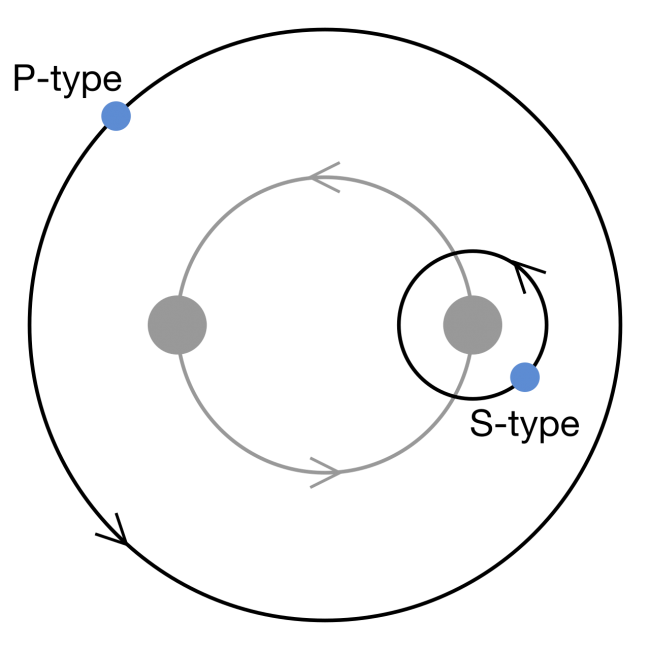

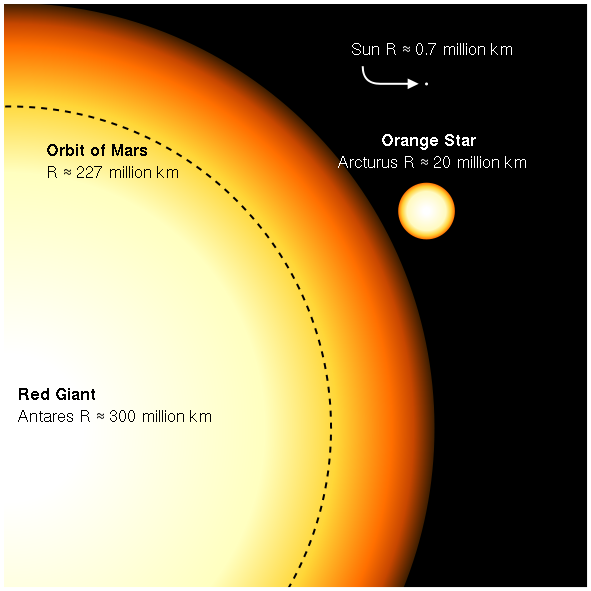

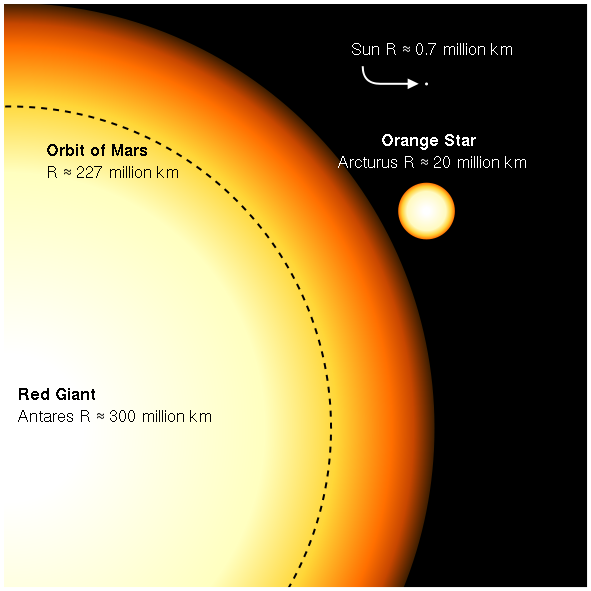

If Antares replaced the sun in our solar system, its circumference would extend beyond the orbit of the fourth planet, Mars. Here, Antares is shown in contrast to another star, Arcturus, and our sun. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Antares science. Antares is truly an enormous star, with a radius in excess of three astronomical units (AU). One AU is the Earth’s average distance from the sun. If by some bit of magic Antares was suddenly substituted for our sun, the surface of the star would extend well past the orbit of Mars!

Antares is classified as an M1 supergiant star. The M1 designation says that Antares is reddish in color and cooler than many other stars. Its surface temperature of 3500 kelvins (about 5800 degrees F or 3200 C) is in contrast to about 10,000 degrees F (5500 C) for our sun.

Even though Antares’ surface temperature is relatively low, Antares’ tremendous surface area – the surface from which light can escape – makes this star very bright. In fact, Antares approaches 11,000 times the brilliance of our puny sun, a G2 star.

But that is just in visible light. When all wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation are considered, Antares pumps out more than 60,000 times the energy of our sun!

Red Antares is similar to but somewhat larger than another famous red star, Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion. Yet Betelgeuse appears slightly brighter than Antares in our sky. Hipparcos satellite data places Antares at about 604 light-years away, in contrast to Betelgeuse’s distance of 428 light-years, explaining why the larger star appears fainter from Earth.

Like all M-type giants and supergiants, Antares is close to the end of its lifetime. Someday soon (astronomically speaking), it will effectively run out of fuel and collapse. The resulting infall of its enormous mass – some 15-18 times the mass of our sun – will cause an immense supernova explosion, ultimately leaving a tiny neutron star or possibly a black hole. This explosion, which could be tomorrow or millions of years from now, will be spectacular as seen from Earth, but we are far enough away that there likely is no danger to our planet.

Scorpius, via Constellation of Words.

Antares in history and myth. Both the Arabic and Latin names for the star Antares mean “heart of the Scorpion.” If you see this constellation in the sky, you’ll find that Antares does indeed seem to reside at the Scorpion’s heart.

Antares is Greek for “like Mars” or “rivaling Mars.” Antares is sometimes said to be the “anti-Mars.” All of this rivalry (or equivalency … for what is rivalry, after all?) stems from the colors of Mars and Antares. Both are red in color, and, for a few months every couple of years Mars is much brighter than Antares. Most of the time, though, Mars is near the same brightness or much fainter than Antares. Every couple of years, Mars passes near Antares, which was perhaps seen as taunting the star, as Mars moves rapidly through the heavens and Antares, like all stars, seems fixed to the starry firmament.

As is typical, more mythology attends the full constellation of Scorpius than the star Antares. Perhaps the most well known story of Scorpius is that the Earth goddess, Gaia, sent him to sting arrogant Orion, who had claimed his intent to kill all animals on the planet. Scorpius killed Orion, and both were placed in the sky, although in opposite sides of the heavens, positioned as if to show the Scorpion chasing the Mighty Hunter.

Interestingly, Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion is similar in appearance to Antares, although brighter. Betelgeuse is not as associated with Mars as is Antares. Although the planet passes in the vicinity of Betelgeuse every couple of years, it never gets as close as it does to Antares.

In Polynesia, Scorpius is often seen as a fishhook, with some stories describing it as the magic fishhook used by the demigod Maui to pull up land from the ocean floor that became the Hawaiian islands. According to the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy website, the Hawaiian name for Antares, Lehua-kona, seems to have little to do with the constellation. It means “southern lehua blossom.”

Antares’ position is RA:16h 29m 24s, dec: -26° 25′ 55″.

The red star Antares, lower left, near the prominent star cluster M4, right. Image via Dick Locke.

Bottom line: How to find the star Antares in your night sky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2LhMFTM

The bright red star Antares, middle, near the prominent star cluster M4, upper right. Photo via Fred Espenak at AstroPixels. Used with permission.

Bright reddish Antares – also known as Alpha Scorpii – is easy to spot on a summer night. It is the brightest star – and distinctly reddish in color – in the fishhook-shaped pattern of stars known as the constellation Scorpius the Scorpion.

Scorpius is one of the few constellations that looks like its namesake. The bright red star Antares marks the Scorpion’s Heart. Notice also the two stars at the tip of the Scorpion’s Tail. They are known as The Stinger.

How to see Antares. If you look southward in early evening from late spring to early fall, you’re likely to notice the fishhook pattern of Scorpius the Scorpion, with ruby Antares at its heart. If you think you’ve found Antares, aim binoculars in its direction. You should notice its reddish color. And you should see a little star cluster – known as M4 – just to the right of this star. (See images above)

Antares is the 16th brightest star in the sky, and it is located in the southern half of Earth’s sky. So your chance of seeing this star on any given night increases as you go farther southward on Earth’s globe. If you traveled to the Southern Hemisphere – from about 67 degrees south latitude – you’d find that Antares is circumpolar, meaning that it never sets and is visible every night of the year from Earth’s southernmost regions.

We in the Northern Hemisphere know Antares better than several other southern stars that are brighter. That’s because Antares is visible from throughout most of the Northern Hemisphere, short of the Arctic. Well, not quite the Arctic, but anywhere south of 63 degrees north latitude can – at one time or another – see Antares. (Helsinki yes, Fairbanks, no)

The midnight culmination of Antares is on or near June 1. That is when Antares is highest in the sky at midnight (midway between sunset and sunrise). It is highest in the sky at about dawn in early March and at about sunset in early September.

If Antares replaced the sun in our solar system, its circumference would extend beyond the orbit of the fourth planet, Mars. Here, Antares is shown in contrast to another star, Arcturus, and our sun. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Antares science. Antares is truly an enormous star, with a radius in excess of three astronomical units (AU). One AU is the Earth’s average distance from the sun. If by some bit of magic Antares was suddenly substituted for our sun, the surface of the star would extend well past the orbit of Mars!

Antares is classified as an M1 supergiant star. The M1 designation says that Antares is reddish in color and cooler than many other stars. Its surface temperature of 3500 kelvins (about 5800 degrees F or 3200 C) is in contrast to about 10,000 degrees F (5500 C) for our sun.

Even though Antares’ surface temperature is relatively low, Antares’ tremendous surface area – the surface from which light can escape – makes this star very bright. In fact, Antares approaches 11,000 times the brilliance of our puny sun, a G2 star.

But that is just in visible light. When all wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation are considered, Antares pumps out more than 60,000 times the energy of our sun!

Red Antares is similar to but somewhat larger than another famous red star, Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion. Yet Betelgeuse appears slightly brighter than Antares in our sky. Hipparcos satellite data places Antares at about 604 light-years away, in contrast to Betelgeuse’s distance of 428 light-years, explaining why the larger star appears fainter from Earth.

Like all M-type giants and supergiants, Antares is close to the end of its lifetime. Someday soon (astronomically speaking), it will effectively run out of fuel and collapse. The resulting infall of its enormous mass – some 15-18 times the mass of our sun – will cause an immense supernova explosion, ultimately leaving a tiny neutron star or possibly a black hole. This explosion, which could be tomorrow or millions of years from now, will be spectacular as seen from Earth, but we are far enough away that there likely is no danger to our planet.

Scorpius, via Constellation of Words.

Antares in history and myth. Both the Arabic and Latin names for the star Antares mean “heart of the Scorpion.” If you see this constellation in the sky, you’ll find that Antares does indeed seem to reside at the Scorpion’s heart.

Antares is Greek for “like Mars” or “rivaling Mars.” Antares is sometimes said to be the “anti-Mars.” All of this rivalry (or equivalency … for what is rivalry, after all?) stems from the colors of Mars and Antares. Both are red in color, and, for a few months every couple of years Mars is much brighter than Antares. Most of the time, though, Mars is near the same brightness or much fainter than Antares. Every couple of years, Mars passes near Antares, which was perhaps seen as taunting the star, as Mars moves rapidly through the heavens and Antares, like all stars, seems fixed to the starry firmament.

As is typical, more mythology attends the full constellation of Scorpius than the star Antares. Perhaps the most well known story of Scorpius is that the Earth goddess, Gaia, sent him to sting arrogant Orion, who had claimed his intent to kill all animals on the planet. Scorpius killed Orion, and both were placed in the sky, although in opposite sides of the heavens, positioned as if to show the Scorpion chasing the Mighty Hunter.

Interestingly, Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion is similar in appearance to Antares, although brighter. Betelgeuse is not as associated with Mars as is Antares. Although the planet passes in the vicinity of Betelgeuse every couple of years, it never gets as close as it does to Antares.

In Polynesia, Scorpius is often seen as a fishhook, with some stories describing it as the magic fishhook used by the demigod Maui to pull up land from the ocean floor that became the Hawaiian islands. According to the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy website, the Hawaiian name for Antares, Lehua-kona, seems to have little to do with the constellation. It means “southern lehua blossom.”

Antares’ position is RA:16h 29m 24s, dec: -26° 25′ 55″.

The red star Antares, lower left, near the prominent star cluster M4, right. Image via Dick Locke.

Bottom line: How to find the star Antares in your night sky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2LhMFTM