In response to the coronavirus outbreak, people across the globe are being asked to work from home where possible in order to limit personal contact and reduce the further spread of the infection.

As of Monday 16 March, the majority of staff and contractors working at ESA mission control began doing just this.

But what implications does this have for the daily work being done to protect space missions from colliding with each other, or orbiting remnants of space debris?

Our planet is now surrounded by thousands of fragments of space junk – defunct satellites or fragments created in previous collisions and explosions.

Satellites in Earth orbit, flying in relatively busy space highways, must be continually protected from hazardous space debris.

On average, ESA performs two collision avoidance manoeuvres per year for each Earth mission it flies. Such manoeuvres divert spacecraft into a safe orbit, ensuring they do not collide with functioning or non-functioning satellites or debris.

Throughout the coronavirus outbreak, work to protect Europe’s space missions will continue.

“We consider the continued monitoring of any potential collisions, and performing manoeuvres to avoid these, one of our highest priorities,” explains Holger Krag, Head of Space Safety.

“We will be able to protect our spacecraft from collisions remotely, even in any much degraded situation with a minimum of personnel and equipment present on site.”

Fortunately, minimising the number of people on site doesn’t mean minimising operations. Close approaches between spacecraft and debris will continue being monitored, and if action is required, those that are needed are ready to come in.

What is a collision avoidance manoeuvre?

When a satellite looks like it will come too close for comfort with another object, either another functioning spacecraft or space debris, mission teams send the commands to get it out of the way.

For a typical satellite in low-Earth orbit, hundreds of alerts are issued every week. For most, the risk of collision decreases as the week goes by and more information is gathered about the orbits of the objects in question.

For the situations that remain risky, hours are spent analysing the distance between the two objects, their likely positions in the future, uncertainties in observations and therefore in calculations and ultimately the probability of collision.

If the probability is greater than typically 1 in 10,000, the work of various teams is needed to prepare a collision avoidance manoeuvre and upload the commands to the satellite.

The manoeuvre must be verified to ensure it will have the expected effect, and doesn’t for example bring the spacecraft closer to the object or even in harm’s way of another object.

As more and more satellites are being launched into Earth orbit, we will soon have more active satellites in orbit than have been launched before in the history of spaceflight.

Read more about past examples of collision avoidance:

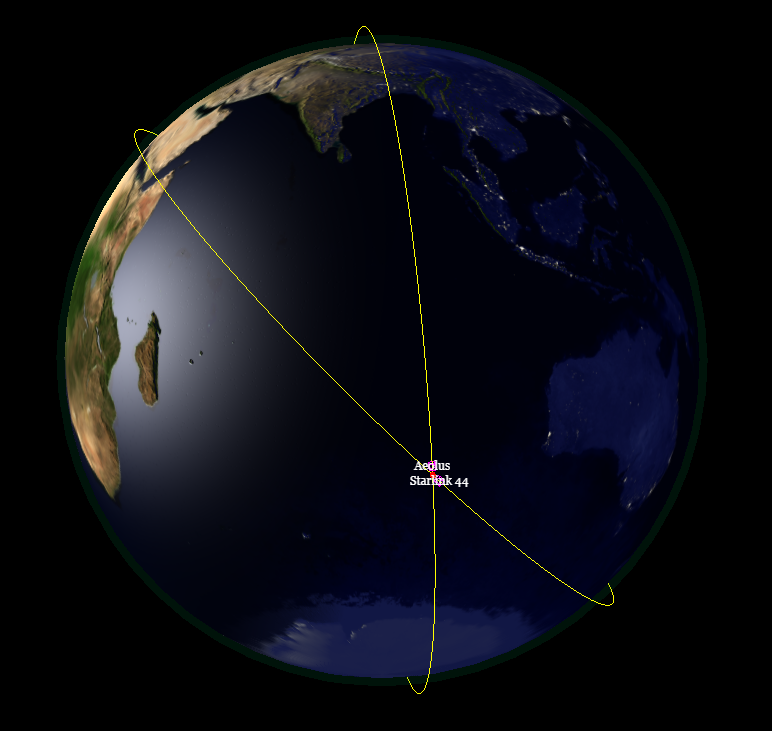

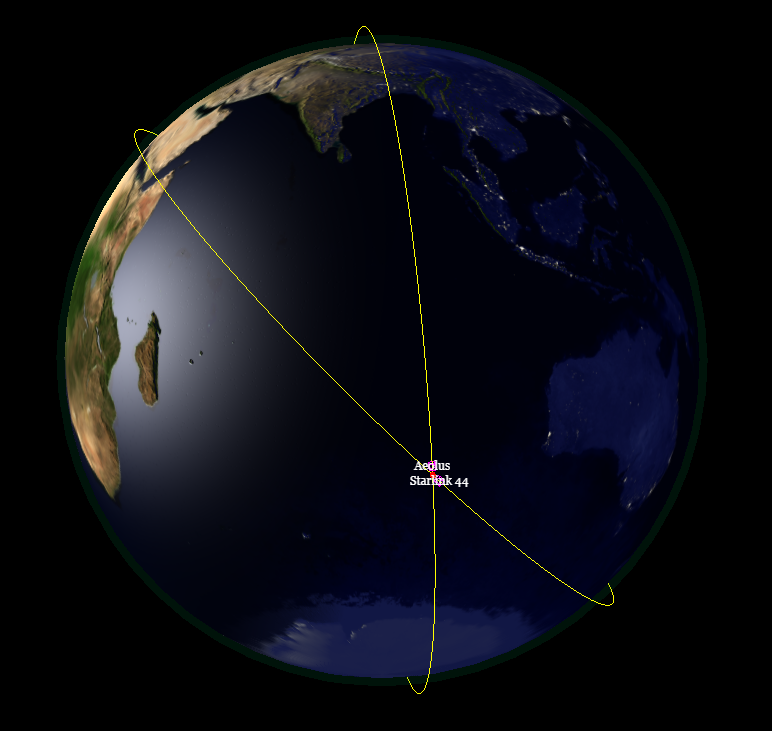

- ESA spacecraft dodges large constellation

- Satellite studying Earth’s diminishing ice swerves to avoid collision

- ESA teams respond to threat to SWARM mission

Automating collision avoidance

ESA is developing a collision avoidance system that will automatically assess the risk and likelihood of in-space collisions, improve the decision making process on whether or not a manoeuvre is needed, and may even send the orders to at-risk satellites to get out of the way.

As these intelligent systems gather more data and experience, they will get better and better at predicting how risky situations evolve, meaning errors in decision making would fall as well as the cost of operations.

Find out more, here.

from Rocket Science https://ift.tt/3deiuHW

v

In response to the coronavirus outbreak, people across the globe are being asked to work from home where possible in order to limit personal contact and reduce the further spread of the infection.

As of Monday 16 March, the majority of staff and contractors working at ESA mission control began doing just this.

But what implications does this have for the daily work being done to protect space missions from colliding with each other, or orbiting remnants of space debris?

Our planet is now surrounded by thousands of fragments of space junk – defunct satellites or fragments created in previous collisions and explosions.

Satellites in Earth orbit, flying in relatively busy space highways, must be continually protected from hazardous space debris.

On average, ESA performs two collision avoidance manoeuvres per year for each Earth mission it flies. Such manoeuvres divert spacecraft into a safe orbit, ensuring they do not collide with functioning or non-functioning satellites or debris.

Throughout the coronavirus outbreak, work to protect Europe’s space missions will continue.

“We consider the continued monitoring of any potential collisions, and performing manoeuvres to avoid these, one of our highest priorities,” explains Holger Krag, Head of Space Safety.

“We will be able to protect our spacecraft from collisions remotely, even in any much degraded situation with a minimum of personnel and equipment present on site.”

Fortunately, minimising the number of people on site doesn’t mean minimising operations. Close approaches between spacecraft and debris will continue being monitored, and if action is required, those that are needed are ready to come in.

What is a collision avoidance manoeuvre?

When a satellite looks like it will come too close for comfort with another object, either another functioning spacecraft or space debris, mission teams send the commands to get it out of the way.

For a typical satellite in low-Earth orbit, hundreds of alerts are issued every week. For most, the risk of collision decreases as the week goes by and more information is gathered about the orbits of the objects in question.

For the situations that remain risky, hours are spent analysing the distance between the two objects, their likely positions in the future, uncertainties in observations and therefore in calculations and ultimately the probability of collision.

If the probability is greater than typically 1 in 10,000, the work of various teams is needed to prepare a collision avoidance manoeuvre and upload the commands to the satellite.

The manoeuvre must be verified to ensure it will have the expected effect, and doesn’t for example bring the spacecraft closer to the object or even in harm’s way of another object.

As more and more satellites are being launched into Earth orbit, we will soon have more active satellites in orbit than have been launched before in the history of spaceflight.

Read more about past examples of collision avoidance:

- ESA spacecraft dodges large constellation

- Satellite studying Earth’s diminishing ice swerves to avoid collision

- ESA teams respond to threat to SWARM mission

Automating collision avoidance

ESA is developing a collision avoidance system that will automatically assess the risk and likelihood of in-space collisions, improve the decision making process on whether or not a manoeuvre is needed, and may even send the orders to at-risk satellites to get out of the way.

As these intelligent systems gather more data and experience, they will get better and better at predicting how risky situations evolve, meaning errors in decision making would fall as well as the cost of operations.

Find out more, here.

from Rocket Science https://ift.tt/3deiuHW

v

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire