View at EarthSky Community Photos. | The first supermoon of 2019 – on January 21 – underwent a total eclipse. Here’s a marvelous time-lapse image of that eclipse from Dennis Schoenfelder in Alamosa, Colorado. One frame every three minutes. Thanks, Dennis!

A supermoon is a new or full moon closely coinciding with perigee, the moon’s closest point to Earth in its monthly orbit. According to the original definition of supermoon – coined by astrologer Richard Nolle in 1979 – a full moon or new moon has to come within 90 percent of its closest approach to Earth to be dubbed a supermoon. In other words, any full moon or new moon that comes to within 224,775 miles or 361,740 km (or less) of our planet, as measured from the centers of the moon and Earth, can be called a supermoon, according to Nolle’s original and extremely generous definition. That’s why you might hear about a number of supermoons in any given year.

So, by Nolle’s definition, when are the supermoons of 2019? We have six of them, three full moons and three new moons.

We had the year’s first supermoon with the January 21, 2019, full moon, which, moreover, staged a total lunar eclipse. The year’s second supermoon – also a full moon – was February 19. The year’s third supermoon – also full – was March 21. Of these, the February 19 full moon showcased the closest and largest full supermoon of 2019.

Now we’re in the midst of a series of new moon supermoons, when the new moon – or moon closest to being between the sun and Earth for any given month – is particularly close. There was one August 1. There are two more coming up on August 30 and September 28.

The second of these three new moon supermoons – on August 30, 2019 – will present the closest new moon supermoon of 2019. Of course, these new moons will be invisible to the eye, crossing the sky with the sun during the day. But they will cause larger-than-usual perigean spring tides, which people living near the coast will surely see and discuss.

Read more: Tides and the pull of the moon and sun

View larger. | You can’t see a new moon in the sky. It’s more or less between the sun and Earth for that monthly orbit and crosses the sky with the sun during the day. Here’s a cool photo taken at the instant of new moon – 07:14 UTC on July 8, 2013 – by Thierry Legault. Read more about this image.

Some astronomers complain about the name supermoon. They call it “hype.” But it’s not hype; it’s just a name that many people now use. We notice even some diehards are starting to use it now. Such is the power of folklore.

Before we called them supermoons, we in astronomy called these moons perigean full moons, or perigean new moons. Perigee just means near Earth.

The moon is full, or opposite Earth from the sun, once each month. It’s new, or more or less between the Earth and sun, once each month. And, every month, as it orbits Earth, the moon comes closest to Earth, or to perigee. The moon naturally swings farthest away once each month, too; that point is called apogee.

No doubt about it. Supermoon is a catchier term than perigean new moon or perigean full moon. That’s probably why the term supermoon has entered the popular culture. For example, Supermoon is the title track of Sophie Hunger’s 2015 album. It’s a nice song! Check it out in the video below.

The “hype” aspect of supermoons probably stems from an erroneous impression people had when the word supermoon came into popular usage … maybe a decade or so ago? Some people mistakenly believed a full supermoon would look much, much bigger to the eye. It doesn’t. Full supermoons don’t look bigger to the eye than ordinary full moons, although experienced observers say they can detect a difference.

But supermoons do look brighter than ordinary full moons! The angular diameter of a supermoon is about 7 percent greater than that of the average-size full moon and 14 percent greater than the angular diameter of a micro-moon (year’s farthest and smallest full moon). Yet, a supermoon exceeds the area (disk size) and brightness of an average-size full moon by some 15 percent – and the micro-moon by some 30 percent. For a visual reference, the size difference between a supermoon and micro-moon is proportionally similar to that of a U.S. quarter versus a U.S. nickel. So go outside on the night of a full supermoon, and – if you’re a regular observer of nature – you’ll surely notice the supermoon is exceptionally bright!

What’s more, Earth’s oceans feel the extra pull of supermoons. All full moons (and new moons) combine with the sun to create larger-than-usual tides, called spring tides. But closer-than-average full moons (or closer-than-average new moons) – that is, supermoons – elevate the tides even more. These extra-high spring tides are wide ranging. High tides climb up especially high, and, on the same day, low tides plunge especially low. Experts call these perigean spring tides, in honor of the moon’s nearness. If you live along an ocean coastline, watch for them! They typically follow the supermoon by a day or two.

Do extra-high supermoon tides cause flooding? Maybe yes, and maybe no. Flooding typically occurs when a strong weather system accompanies an especially high spring tide.

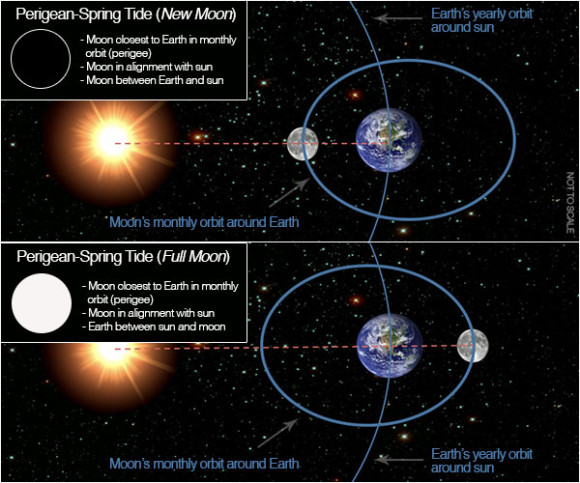

Around each new moon (left) and full moon (right) – when the sun, Earth, and moon are located more or less on a line in space – the range between high and low tides is greatest. These are called spring tides. A supermoon – new or full moon at its closest to Earth – accentuates these tides. Image via physicalgeography.net.

About 3 or 4 times a year, or more often, a new or full moon coincides with the moon’s closest point to Earth, or perigee. There’s usually only a small difference – typically a couple of inches (or centimeters) – between these “perigean spring tides” and normal tidal ranges. But, at these times, if a storm strikes along a coastline, flooding can occur. Image via NOAA.

How often do we have supermoons? Often! But of course it depends on your definition of supermoon. Here’s a list of the year’s closest supermoons from 2010 to 2020 (they all came closer than 357,000 kilometers or 221,830 miles):

January 30, 2010 (356,593 km or 221,577 mi)

March 19, 2011 (356,575 km or 221,565 miles)

May 6, 2012 (356,955 km or 221,802 miles)

June 23, 2013 (356,991 km or 221,824 miles)

August 10, 2014 (356,896 km or 221,765 miles)

September 28, 2015 (356,877 km or 221,753 miles)

November 14, 2016 (356,509 km or 221,524 miles)

January 2, 2018 (356,565 km or 221,559 miles)

February 19, 2019 (356,761 km or 221,681 miles)

April 8, 2020 (356,907 km or 221,772 miles)

There wasn’t an extra-close perigee full moon – a closest full supermoon – in 2017 (by “extra-close,” we’re considering moons less than 357,000 kilometers or 221,830 miles from Earth). After November 14, 2016, the extra-close coincidence of full moon and perigee didn’t happen again until January 1-2, 2018.

Looking farther into the future, the perigee full moon will come closer than 356,500 kilometers (221,519 miles) for the first time in the 21st century (2001-2100) on November 25, 2034 (356,446 km or 221,485 mi). The closest full moon of the 21st century will fall on December 6, 2052 (356,425 km or 221,472 mi).

By the way, some astronomers call the full moons listed above proxigee full moons. The word proxigee just means an extra-close perigee.

But, like many of you, we’ll have fun just calling ’em supermoons.

Happy supermoons, y’all! This great moon photo comes from EarthSky Facebook friend Rebecca Lacey in Cambridge, Idaho.

So, just how much closer are these close full and new moons? This year, 2019, the moon at its closest point to Earth resides 221,681 miles (356,761 km) away. At this juncture, the moon is said to be at 100 percent of its closest approach for the year.

In 2019, the moon at its farthest point swings out to 252,622 miles (406,555 km) from Earth. At that time, the moon is said to be at 0 percent of its closest approach.

At its closest point for the year, the moon is approximately 30,000 miles or 50,000 km closer than when the moon is most distant.

The full moon supermoon series of 2019 will recur after 14 lunar months (14 returns to full moon). That’s because 14 returns to full moon almost exactly equal 15 returns to perigee, a period of about one year, one month, and 18 days:

Full moon distance (March 9, 2020): 222,081 miles or 357,404 km

Full moon distance (April 8, 2020): 221,851 miles or 357,035 km

Full moon distance (May 7, 2020): 224,429 miles or 361,184 km

The new moon supermoon series will also recur after 14 lunar months (14 returns to new moon). Thus, we’ll have new supermoons on September 17, October 16 and November 15, 2020.

Here’s a comparison between the December 3, 2017, full moon at perigee (closest to Earth for the month) and the year’s farthest full moon in June 2017 at apogee (farthest from Earth for the month) by Muzamir Mazlan at Telok Kemang Observatory, Port Dickson, Malaysia. More photos of the December 2017 supermoon.

Bottom line: The first three full moons of 2019 are supermoons. The next supermoons of 2019 will be the new moons of August 1 and 30 plus September 28.

Read more: Why experts disagree on what’s a supermoon

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Pejc01

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | The first supermoon of 2019 – on January 21 – underwent a total eclipse. Here’s a marvelous time-lapse image of that eclipse from Dennis Schoenfelder in Alamosa, Colorado. One frame every three minutes. Thanks, Dennis!

A supermoon is a new or full moon closely coinciding with perigee, the moon’s closest point to Earth in its monthly orbit. According to the original definition of supermoon – coined by astrologer Richard Nolle in 1979 – a full moon or new moon has to come within 90 percent of its closest approach to Earth to be dubbed a supermoon. In other words, any full moon or new moon that comes to within 224,775 miles or 361,740 km (or less) of our planet, as measured from the centers of the moon and Earth, can be called a supermoon, according to Nolle’s original and extremely generous definition. That’s why you might hear about a number of supermoons in any given year.

So, by Nolle’s definition, when are the supermoons of 2019? We have six of them, three full moons and three new moons.

We had the year’s first supermoon with the January 21, 2019, full moon, which, moreover, staged a total lunar eclipse. The year’s second supermoon – also a full moon – was February 19. The year’s third supermoon – also full – was March 21. Of these, the February 19 full moon showcased the closest and largest full supermoon of 2019.

Now we’re in the midst of a series of new moon supermoons, when the new moon – or moon closest to being between the sun and Earth for any given month – is particularly close. There was one August 1. There are two more coming up on August 30 and September 28.

The second of these three new moon supermoons – on August 30, 2019 – will present the closest new moon supermoon of 2019. Of course, these new moons will be invisible to the eye, crossing the sky with the sun during the day. But they will cause larger-than-usual perigean spring tides, which people living near the coast will surely see and discuss.

Read more: Tides and the pull of the moon and sun

View larger. | You can’t see a new moon in the sky. It’s more or less between the sun and Earth for that monthly orbit and crosses the sky with the sun during the day. Here’s a cool photo taken at the instant of new moon – 07:14 UTC on July 8, 2013 – by Thierry Legault. Read more about this image.

Some astronomers complain about the name supermoon. They call it “hype.” But it’s not hype; it’s just a name that many people now use. We notice even some diehards are starting to use it now. Such is the power of folklore.

Before we called them supermoons, we in astronomy called these moons perigean full moons, or perigean new moons. Perigee just means near Earth.

The moon is full, or opposite Earth from the sun, once each month. It’s new, or more or less between the Earth and sun, once each month. And, every month, as it orbits Earth, the moon comes closest to Earth, or to perigee. The moon naturally swings farthest away once each month, too; that point is called apogee.

No doubt about it. Supermoon is a catchier term than perigean new moon or perigean full moon. That’s probably why the term supermoon has entered the popular culture. For example, Supermoon is the title track of Sophie Hunger’s 2015 album. It’s a nice song! Check it out in the video below.

The “hype” aspect of supermoons probably stems from an erroneous impression people had when the word supermoon came into popular usage … maybe a decade or so ago? Some people mistakenly believed a full supermoon would look much, much bigger to the eye. It doesn’t. Full supermoons don’t look bigger to the eye than ordinary full moons, although experienced observers say they can detect a difference.

But supermoons do look brighter than ordinary full moons! The angular diameter of a supermoon is about 7 percent greater than that of the average-size full moon and 14 percent greater than the angular diameter of a micro-moon (year’s farthest and smallest full moon). Yet, a supermoon exceeds the area (disk size) and brightness of an average-size full moon by some 15 percent – and the micro-moon by some 30 percent. For a visual reference, the size difference between a supermoon and micro-moon is proportionally similar to that of a U.S. quarter versus a U.S. nickel. So go outside on the night of a full supermoon, and – if you’re a regular observer of nature – you’ll surely notice the supermoon is exceptionally bright!

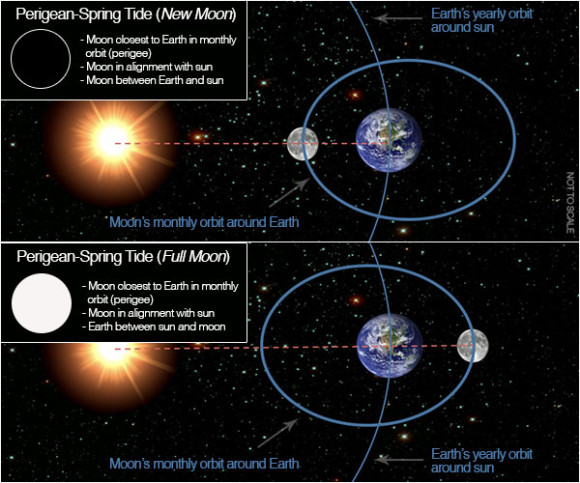

What’s more, Earth’s oceans feel the extra pull of supermoons. All full moons (and new moons) combine with the sun to create larger-than-usual tides, called spring tides. But closer-than-average full moons (or closer-than-average new moons) – that is, supermoons – elevate the tides even more. These extra-high spring tides are wide ranging. High tides climb up especially high, and, on the same day, low tides plunge especially low. Experts call these perigean spring tides, in honor of the moon’s nearness. If you live along an ocean coastline, watch for them! They typically follow the supermoon by a day or two.

Do extra-high supermoon tides cause flooding? Maybe yes, and maybe no. Flooding typically occurs when a strong weather system accompanies an especially high spring tide.

Around each new moon (left) and full moon (right) – when the sun, Earth, and moon are located more or less on a line in space – the range between high and low tides is greatest. These are called spring tides. A supermoon – new or full moon at its closest to Earth – accentuates these tides. Image via physicalgeography.net.

About 3 or 4 times a year, or more often, a new or full moon coincides with the moon’s closest point to Earth, or perigee. There’s usually only a small difference – typically a couple of inches (or centimeters) – between these “perigean spring tides” and normal tidal ranges. But, at these times, if a storm strikes along a coastline, flooding can occur. Image via NOAA.

How often do we have supermoons? Often! But of course it depends on your definition of supermoon. Here’s a list of the year’s closest supermoons from 2010 to 2020 (they all came closer than 357,000 kilometers or 221,830 miles):

January 30, 2010 (356,593 km or 221,577 mi)

March 19, 2011 (356,575 km or 221,565 miles)

May 6, 2012 (356,955 km or 221,802 miles)

June 23, 2013 (356,991 km or 221,824 miles)

August 10, 2014 (356,896 km or 221,765 miles)

September 28, 2015 (356,877 km or 221,753 miles)

November 14, 2016 (356,509 km or 221,524 miles)

January 2, 2018 (356,565 km or 221,559 miles)

February 19, 2019 (356,761 km or 221,681 miles)

April 8, 2020 (356,907 km or 221,772 miles)

There wasn’t an extra-close perigee full moon – a closest full supermoon – in 2017 (by “extra-close,” we’re considering moons less than 357,000 kilometers or 221,830 miles from Earth). After November 14, 2016, the extra-close coincidence of full moon and perigee didn’t happen again until January 1-2, 2018.

Looking farther into the future, the perigee full moon will come closer than 356,500 kilometers (221,519 miles) for the first time in the 21st century (2001-2100) on November 25, 2034 (356,446 km or 221,485 mi). The closest full moon of the 21st century will fall on December 6, 2052 (356,425 km or 221,472 mi).

By the way, some astronomers call the full moons listed above proxigee full moons. The word proxigee just means an extra-close perigee.

But, like many of you, we’ll have fun just calling ’em supermoons.

Happy supermoons, y’all! This great moon photo comes from EarthSky Facebook friend Rebecca Lacey in Cambridge, Idaho.

So, just how much closer are these close full and new moons? This year, 2019, the moon at its closest point to Earth resides 221,681 miles (356,761 km) away. At this juncture, the moon is said to be at 100 percent of its closest approach for the year.

In 2019, the moon at its farthest point swings out to 252,622 miles (406,555 km) from Earth. At that time, the moon is said to be at 0 percent of its closest approach.

At its closest point for the year, the moon is approximately 30,000 miles or 50,000 km closer than when the moon is most distant.

The full moon supermoon series of 2019 will recur after 14 lunar months (14 returns to full moon). That’s because 14 returns to full moon almost exactly equal 15 returns to perigee, a period of about one year, one month, and 18 days:

Full moon distance (March 9, 2020): 222,081 miles or 357,404 km

Full moon distance (April 8, 2020): 221,851 miles or 357,035 km

Full moon distance (May 7, 2020): 224,429 miles or 361,184 km

The new moon supermoon series will also recur after 14 lunar months (14 returns to new moon). Thus, we’ll have new supermoons on September 17, October 16 and November 15, 2020.

Here’s a comparison between the December 3, 2017, full moon at perigee (closest to Earth for the month) and the year’s farthest full moon in June 2017 at apogee (farthest from Earth for the month) by Muzamir Mazlan at Telok Kemang Observatory, Port Dickson, Malaysia. More photos of the December 2017 supermoon.

Bottom line: The first three full moons of 2019 are supermoons. The next supermoons of 2019 will be the new moons of August 1 and 30 plus September 28.

Read more: Why experts disagree on what’s a supermoon

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Pejc01