Click the name of a planet to learn more about its visibility in June 2019: Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Mars and Mercury.

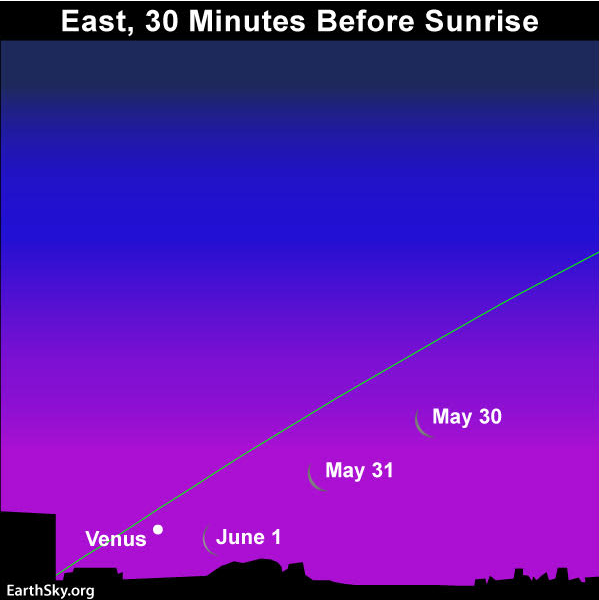

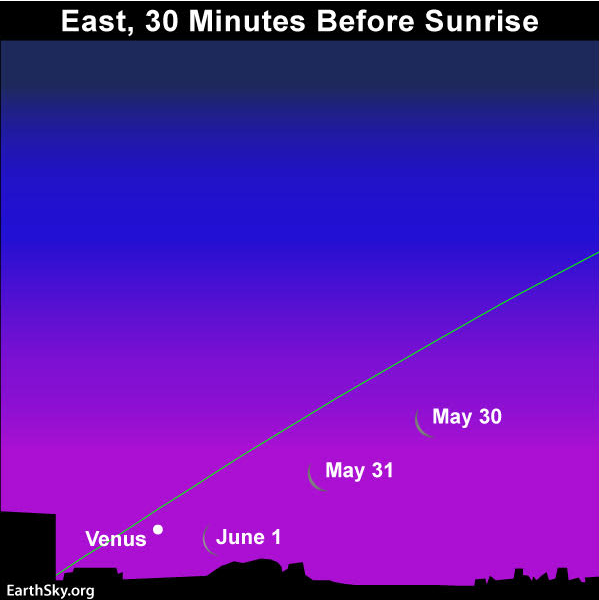

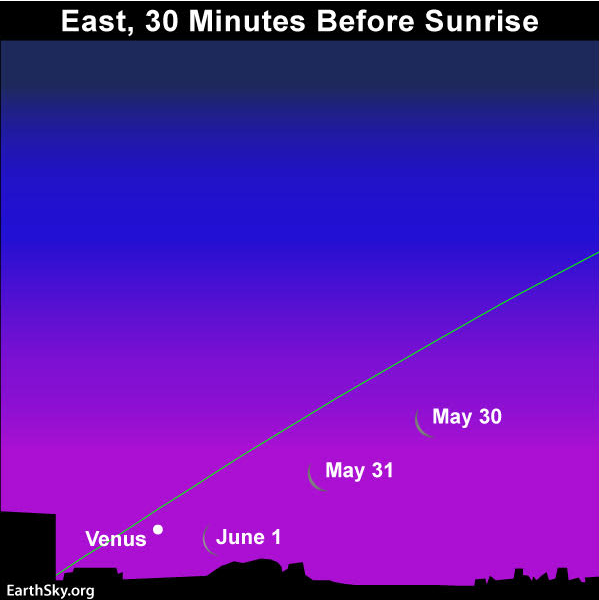

The waning crescent moon pairs up with the queen planet Venus on or near June 1. Read more.

Venus is the brightest planet, looming low in the east before sunrise. With some diligence, you may catch the waning crescent moon with Venus on June 1 (see June chart above).

From northerly latitudes, Venus sits in the glare of morning twilight. The northern tropics and Southern Hemisphere enjoy a less obstructed view. For all of us, Venus starts out the month at an elongation of 20 degrees west of the sun. It ends the month at 12 degrees west of the sun. Despite Venus being the same angular distance from the sun worldwide, Venus spends more time lighting up the morning twilight at more southerly latitudes. That’s because the ecliptic – pathway of the sun, moon and planets in front of the constellations of the zodiac – appears more nearly vertical with respect to the sunrise horizon from southerly latitudes.

In June, at mid-northern latitudes, Venus rises well after the beginning of astronomical twilight (dawn’s first light) all month long. At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Venus comes up before the advent of astronomical twilight in early June 2019.

Click here to find out when astronomical twilight comes to your sky, remembering to check the astronomical twilight box.

At mid-northern latitudes, Venus rises about one hour before sunrise in early June. By the month’s end, that’ll taper to about 50 minutes.

At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Venus rises about 1 1/2 hours before sunup in early June. By the month’s end that’ll decrease to about 50 minutes, as well.

Your last chance of catching the moon and Venus together in the morning sky this year might well be June 1. Next month, in July 2019, Venus will plunge even deeper into the glare of sunrise; and then, in August 2019, Venus will transition from the morning to evening sky.

If you live at the just the right spot in South America, look for Venus to pop into view at daytime during the total eclipse of the sun on July 2, 2019.

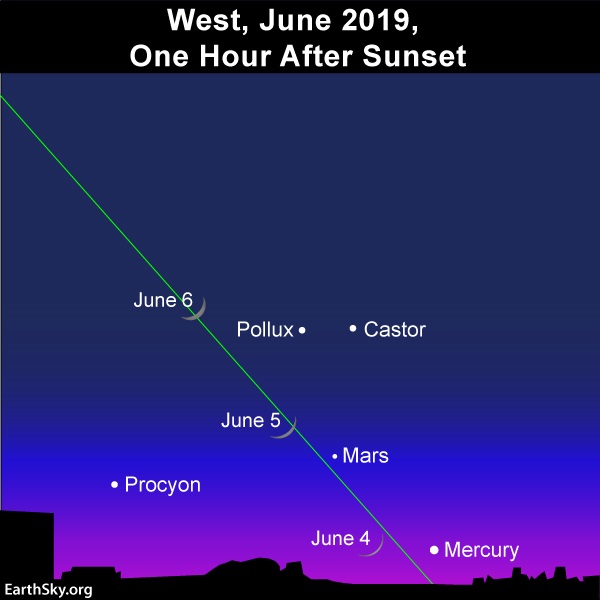

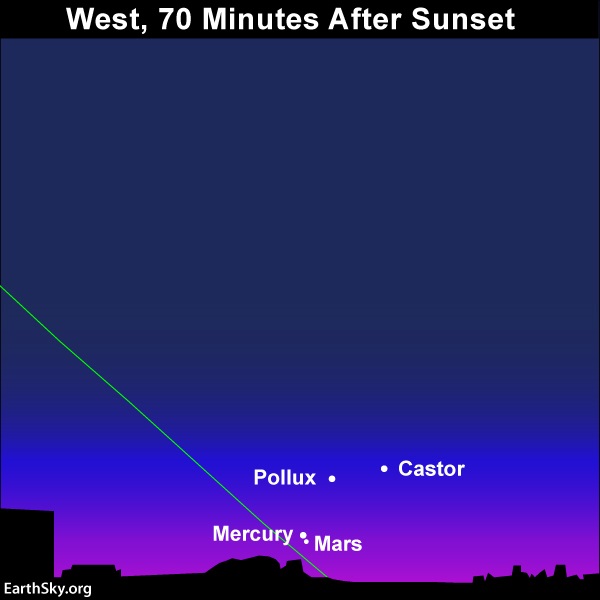

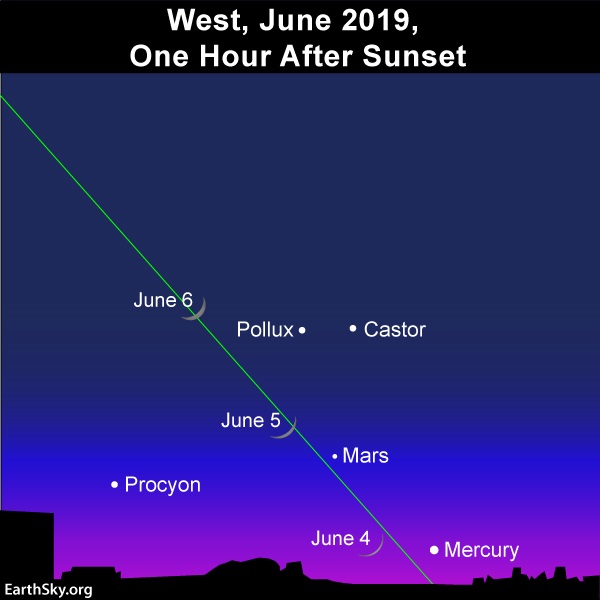

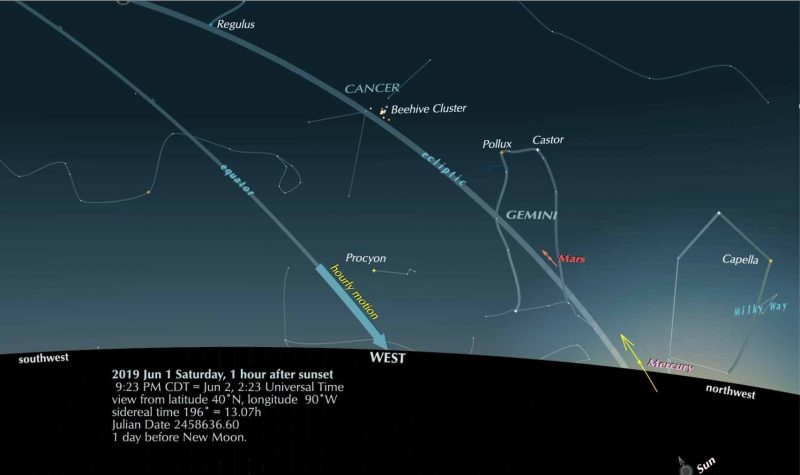

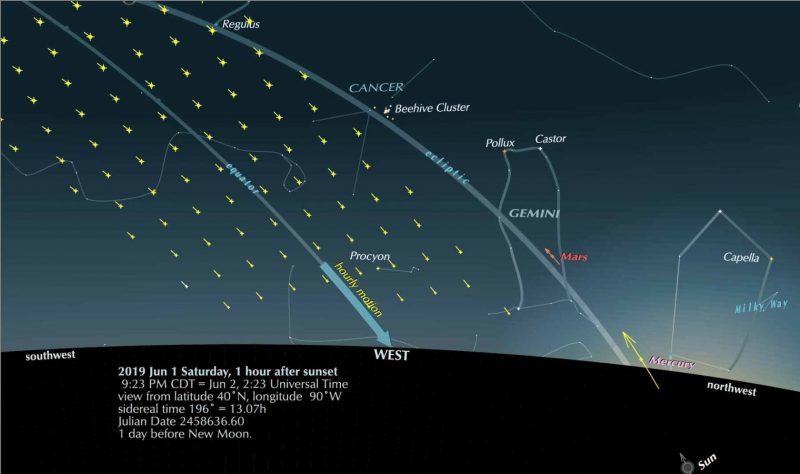

You might be able to see the young moon and the planet Mercury with the eye alone on June 4. But just in case, you may want to bring binoculars! Read more.

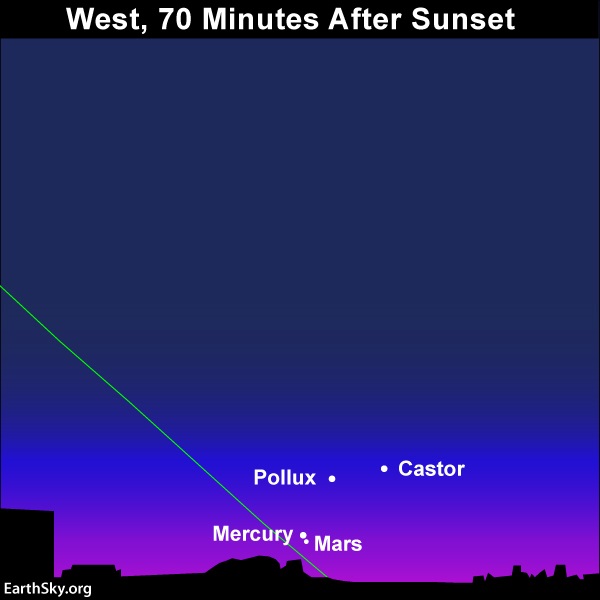

Mercury, the innermost planet of the solar system, is expected to become a fine evening object from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres in June 2019. Even though this world won’t reach its greatest elongation from the sun until June 23, you still might catch this world in early June. Be sure to look for the young crescent moon near Mercury, starting around June 4. See the above sky chart.

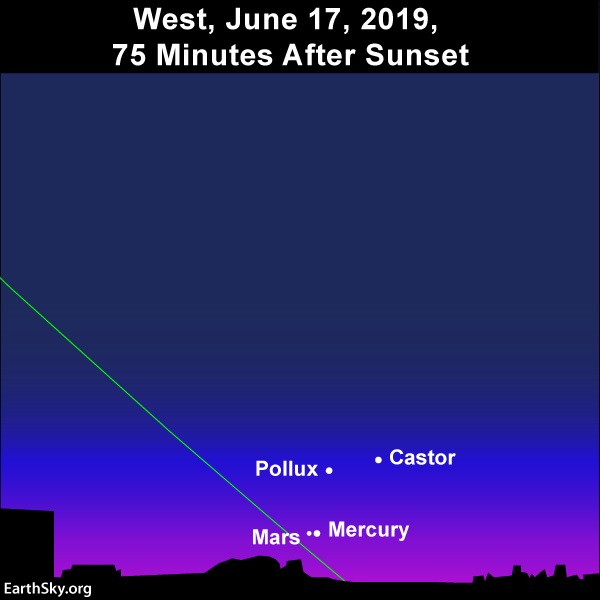

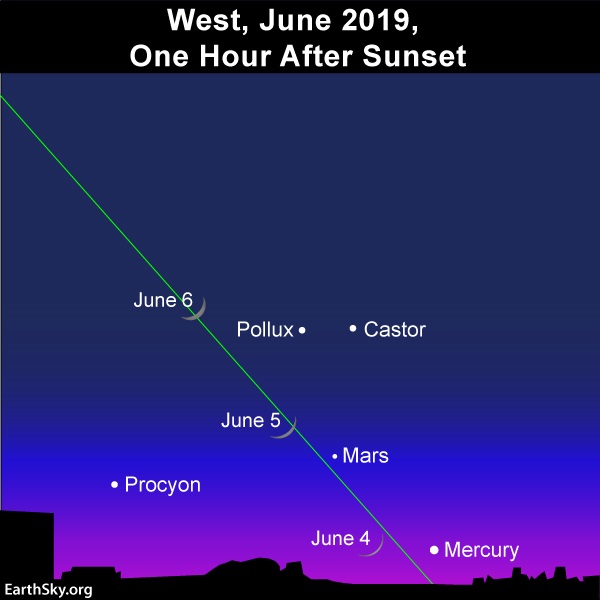

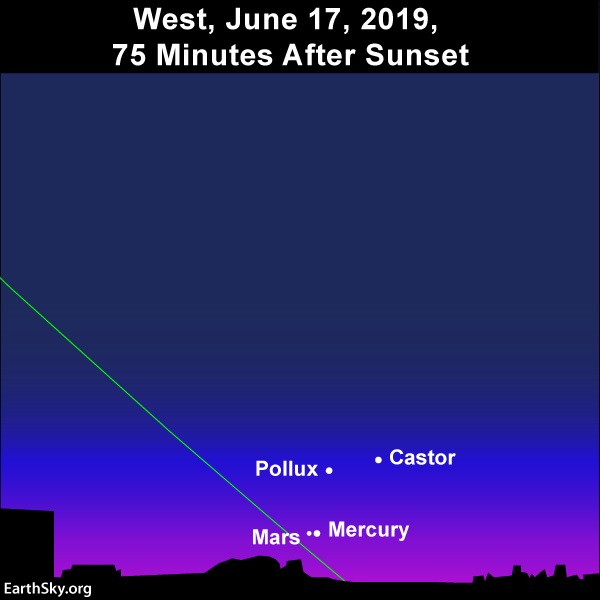

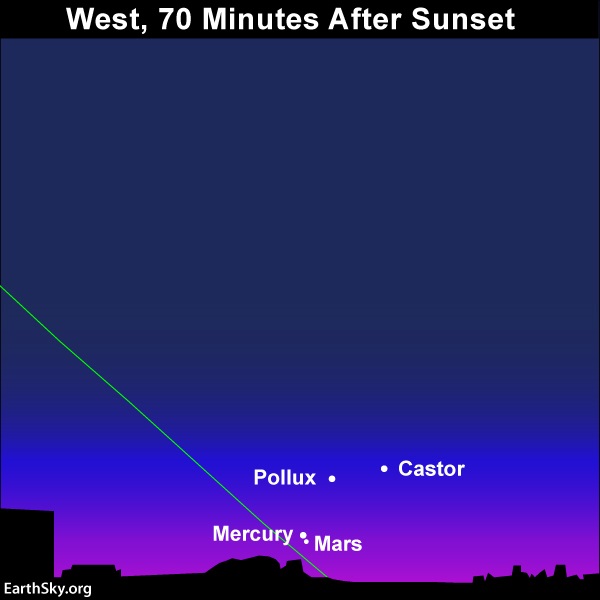

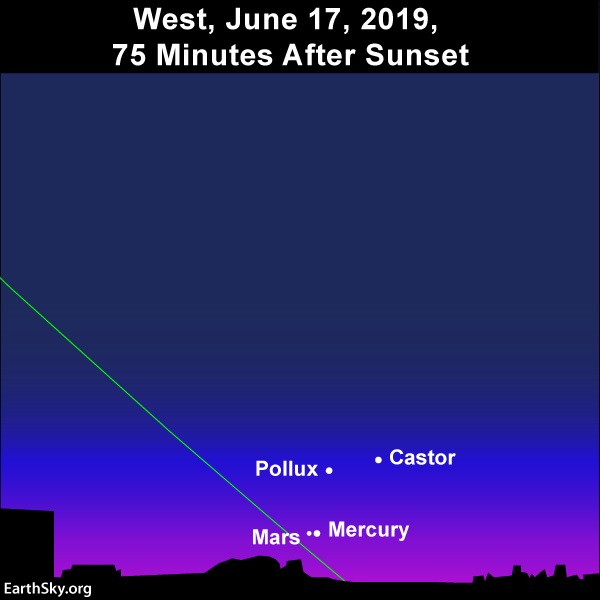

Mercury starts off the month below Mars. Day by day, Mercury will climb upward whereas Mars will descend downward, with the two meeting up for a close encounter on the sky’s dome on June 17 and 18, 2019. At their closest, these two worlds will be a scant 0.2 degrees (less than 1/2 the moon’s diameter) apart, to stage the closest conjunction of two planets in 2019. See the sky chart below for June 17.

As seen from North America, Mercury and Mars stand side by side after sunset June 17, 2019. Read more.

Jupiter is the second-brightest planet after Venus. Yet it’s the king planet Jupiter that reigns supreme in the June 2019 nighttime sky. Venus is pretty much lost in the glare of sunrise throughout June, whereas Jupiter shines at its brightest best for year, beaming away from dusk till dawn. There’s no mistaking Venus for Jupiter in June 2019!

Jupiter is now approaching its yearly opposition, marking the best time of year to see this brilliant beauty. Jupiter ranks as the 4th-brightest celestial object to light up the heavens, after the sun, moon and Venus. At opposition on June 10, 2019, look for Jupiter to rise at sunset, soar highest up for the night at midnight, and to set at sunrise. Click here for an almanac telling you when Jupiter rises/transits/sets in your sky, remembering to pick Jupiter as your celestial object of interest.

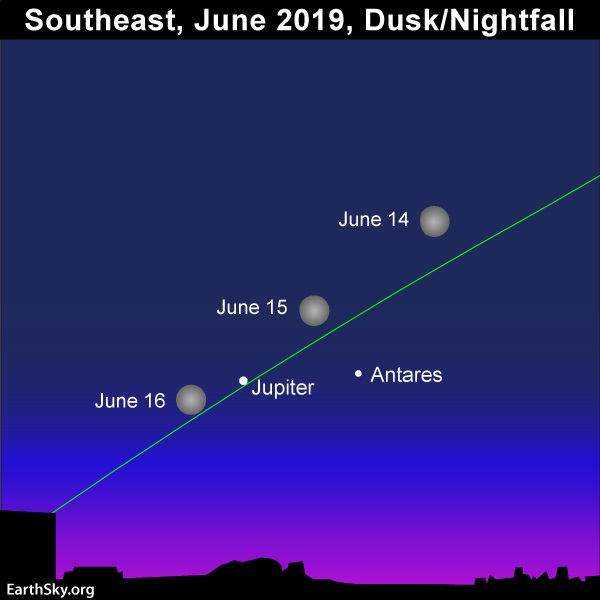

That bright ruddy star rather close to Jupiter is Antares, the brightest star in the constellation Scorpius the Scorpion. Although Jupiter shines in the vicinity of Antares throughout 2019, Jupiter can be seen to wander relative to this “fixed” star of the zodiac. This year, in the first three months of 2019, Jupiter was traveling eastward, away from Antares. But starting on April 10, 2019, Jupiter reversed course, moving toward Antares. For the following four months (April 10 to August 11, 2019), Jupiter will be traveling in retrograde (or westward), closing the gap between itself and the star Antares. Midway through this retrograde, on June 10, 2019, Jupiter will reach opposition.

From around the world in early June, Jupiter rises about 1/2 hour after sunset. By June 10, Jupiter rises as the sun sets. Thereafter, Jupiter enters the stage of sky before sunset.

Jupiter comes up first in the nightly procession of three bright planets. Saturn follows Jupiter into the sky about two hours after Jupiter first appears, and then Venus struggles to make a brief appearance in the eastern morning twilight.

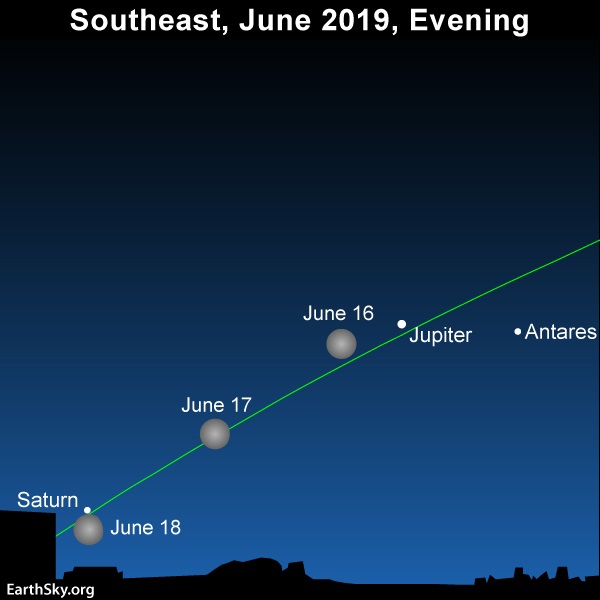

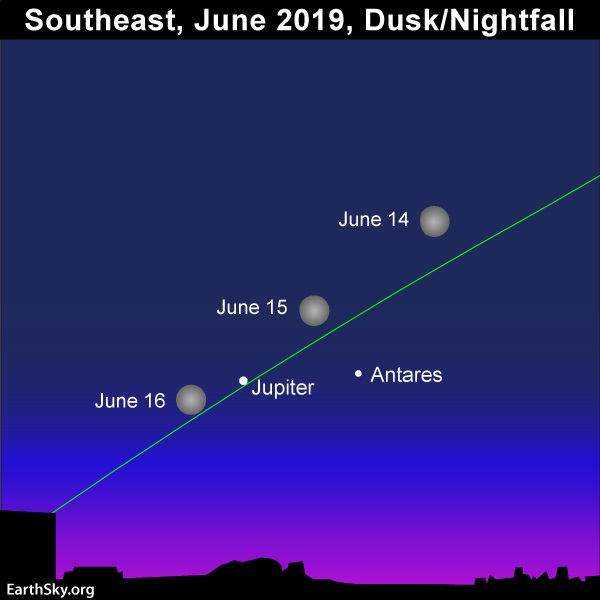

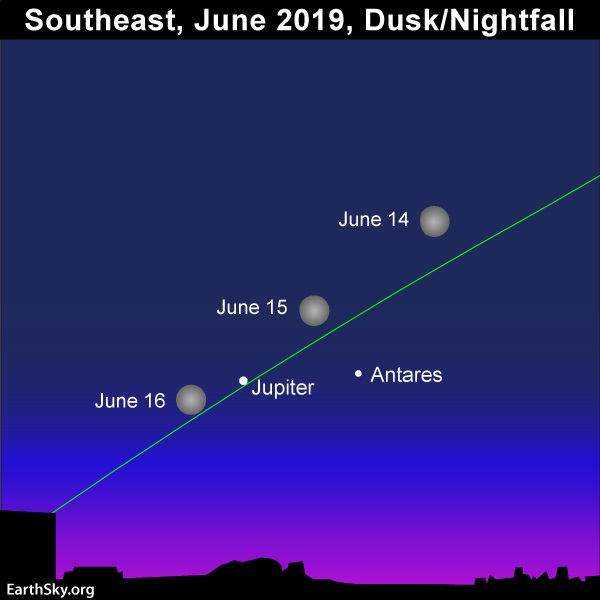

Watch for the waning gibbous moon to swing by Jupiter on the evenings of June 14, 15 and 16, as displayed on the sky chart below.

Watch the bright moon swing close to Jupiter on June 14, 15 and 18. Read more.

Saturn comes up up a few hours after Jupiter. Throughout June, Saturn and Jupiter rise earlier each day, both of them to climb above the horizon about two hours earlier by the month’s end. Saturn, although as bright as a 1st-magnitude star, pales in contrast to Jupiter. Jupiter outshines Saturn by some 14 times.

From mid-northern latitudes, Saturn comes up about two hours before the midnight hour (11 p.m. daylight saving time) in early June. (As a reminder, midnight in our usage means midway between sunset and sunrise.) By the month’s end, Saturn will rise around nightfall.

From temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Saturn rises at or around 8 p.m. in early June. By the month’s end, Saturn will rise by nightfall.

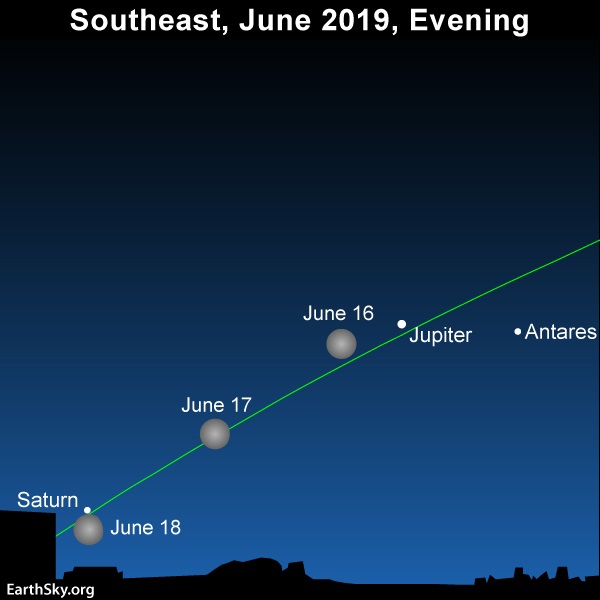

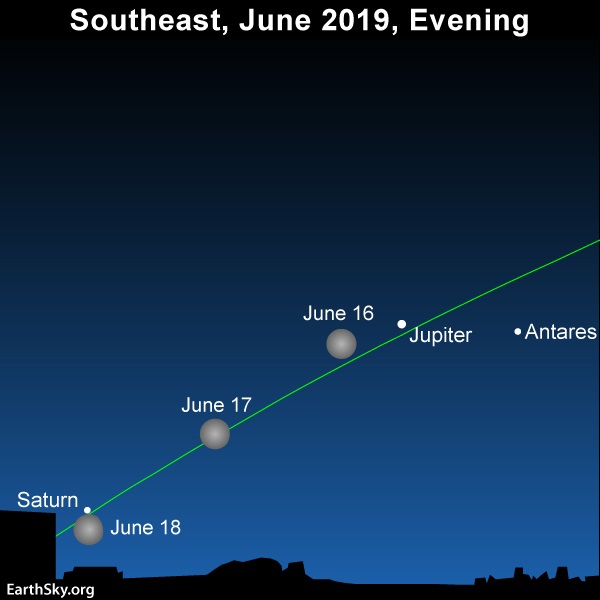

Watch for the waning moon to couple up with Saturn around June 18, as shown on the sky chart below. If you’re in just the right spot in South America, you can actually watch the moon occult (cover over) Saturn. Click here to find out more.

For the several days from June 16 to June 18, watch as the moon moves from Jupiter to Saturn. Read more.

Mars lurks low in the west at dusk/nightfall and follows the sun beneath the horizon shortly thereafter. Mars has faded into 2nd-magnitude brightness, which makes this world all the harder to spot. Given a dark sky and some diligent searching, you should be able to spot this world in your western sky at early evening.

Click here for recommended sky almanacs providing you with the setting times for Mars for your location.

Watch for the young crescent moon to shine in the vicinity of Mars for several evenings, centered on or near June 6. The moon’s proximity might provide you with your best opportunity to catch Mars in the evening sky for the rest of 2019. Day by day, this planet is slowly but surely fading, and sinking closer to the afterglow of sunset.

Starting on June 12 or thereabouts, Mercury will be close enough to Mars for the twosome to take stage in a single binocular field. After that, look for Mercury and Mars to occupy the same binocular field till nearly the end of the month. Watch for Mercury and Mars to snuggle up quite close together in the evening sky on June 17, 18 and 19, with Mercury passing a scant 0.2 degrees north of Mars on June 18, to present the closest conjunction of two planets in 2019.

Look westward for the close pairing of the planets Mercury and Mars on June 18, 2019. You may need binoculars to glimpse fainter Mars next to brighter Mercury. Read more.

What do we mean by bright planet? By bright planet, we mean any solar system planet that is easily visible without an optical aid and that has been watched by our ancestors since time immemorial. In their outward order from the sun, the five bright planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. These planets actually do appear bright in our sky. They are typically as bright as – or brighter than – the brightest stars. Plus, these relatively nearby worlds tend to shine with a steadier light than the distant, twinkling stars. You can spot them, and come to know them as faithful friends, if you try.

Skywatcher, by Predrag Agatonovic.

Bottom line: In June 2019, Jupiter beams from dusk till dawn, whereas Venus fleetingly shows itself in the east before sunrise. Saturn is out from mid-evening till dawn. Mercury and Mars lurk low in the west at dusk, and showcase the year’s closest conjunction of two planets on June 18, 2019. Click here for recommended almanacs; they can help you know when the planets rise and set in your sky.

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to EarthSky News by email

Visit EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze, and recommend a place we can all enjoy. Zoom out for worldwide map.

Help EarthSky keep going! Donate now.

Post your planet photos at EarthSky Community Photos

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/1YD00CF

Click the name of a planet to learn more about its visibility in June 2019: Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Mars and Mercury.

The waning crescent moon pairs up with the queen planet Venus on or near June 1. Read more.

Venus is the brightest planet, looming low in the east before sunrise. With some diligence, you may catch the waning crescent moon with Venus on June 1 (see June chart above).

From northerly latitudes, Venus sits in the glare of morning twilight. The northern tropics and Southern Hemisphere enjoy a less obstructed view. For all of us, Venus starts out the month at an elongation of 20 degrees west of the sun. It ends the month at 12 degrees west of the sun. Despite Venus being the same angular distance from the sun worldwide, Venus spends more time lighting up the morning twilight at more southerly latitudes. That’s because the ecliptic – pathway of the sun, moon and planets in front of the constellations of the zodiac – appears more nearly vertical with respect to the sunrise horizon from southerly latitudes.

In June, at mid-northern latitudes, Venus rises well after the beginning of astronomical twilight (dawn’s first light) all month long. At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Venus comes up before the advent of astronomical twilight in early June 2019.

Click here to find out when astronomical twilight comes to your sky, remembering to check the astronomical twilight box.

At mid-northern latitudes, Venus rises about one hour before sunrise in early June. By the month’s end, that’ll taper to about 50 minutes.

At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Venus rises about 1 1/2 hours before sunup in early June. By the month’s end that’ll decrease to about 50 minutes, as well.

Your last chance of catching the moon and Venus together in the morning sky this year might well be June 1. Next month, in July 2019, Venus will plunge even deeper into the glare of sunrise; and then, in August 2019, Venus will transition from the morning to evening sky.

If you live at the just the right spot in South America, look for Venus to pop into view at daytime during the total eclipse of the sun on July 2, 2019.

You might be able to see the young moon and the planet Mercury with the eye alone on June 4. But just in case, you may want to bring binoculars! Read more.

Mercury, the innermost planet of the solar system, is expected to become a fine evening object from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres in June 2019. Even though this world won’t reach its greatest elongation from the sun until June 23, you still might catch this world in early June. Be sure to look for the young crescent moon near Mercury, starting around June 4. See the above sky chart.

Mercury starts off the month below Mars. Day by day, Mercury will climb upward whereas Mars will descend downward, with the two meeting up for a close encounter on the sky’s dome on June 17 and 18, 2019. At their closest, these two worlds will be a scant 0.2 degrees (less than 1/2 the moon’s diameter) apart, to stage the closest conjunction of two planets in 2019. See the sky chart below for June 17.

As seen from North America, Mercury and Mars stand side by side after sunset June 17, 2019. Read more.

Jupiter is the second-brightest planet after Venus. Yet it’s the king planet Jupiter that reigns supreme in the June 2019 nighttime sky. Venus is pretty much lost in the glare of sunrise throughout June, whereas Jupiter shines at its brightest best for year, beaming away from dusk till dawn. There’s no mistaking Venus for Jupiter in June 2019!

Jupiter is now approaching its yearly opposition, marking the best time of year to see this brilliant beauty. Jupiter ranks as the 4th-brightest celestial object to light up the heavens, after the sun, moon and Venus. At opposition on June 10, 2019, look for Jupiter to rise at sunset, soar highest up for the night at midnight, and to set at sunrise. Click here for an almanac telling you when Jupiter rises/transits/sets in your sky, remembering to pick Jupiter as your celestial object of interest.

That bright ruddy star rather close to Jupiter is Antares, the brightest star in the constellation Scorpius the Scorpion. Although Jupiter shines in the vicinity of Antares throughout 2019, Jupiter can be seen to wander relative to this “fixed” star of the zodiac. This year, in the first three months of 2019, Jupiter was traveling eastward, away from Antares. But starting on April 10, 2019, Jupiter reversed course, moving toward Antares. For the following four months (April 10 to August 11, 2019), Jupiter will be traveling in retrograde (or westward), closing the gap between itself and the star Antares. Midway through this retrograde, on June 10, 2019, Jupiter will reach opposition.

From around the world in early June, Jupiter rises about 1/2 hour after sunset. By June 10, Jupiter rises as the sun sets. Thereafter, Jupiter enters the stage of sky before sunset.

Jupiter comes up first in the nightly procession of three bright planets. Saturn follows Jupiter into the sky about two hours after Jupiter first appears, and then Venus struggles to make a brief appearance in the eastern morning twilight.

Watch for the waning gibbous moon to swing by Jupiter on the evenings of June 14, 15 and 16, as displayed on the sky chart below.

Watch the bright moon swing close to Jupiter on June 14, 15 and 18. Read more.

Saturn comes up up a few hours after Jupiter. Throughout June, Saturn and Jupiter rise earlier each day, both of them to climb above the horizon about two hours earlier by the month’s end. Saturn, although as bright as a 1st-magnitude star, pales in contrast to Jupiter. Jupiter outshines Saturn by some 14 times.

From mid-northern latitudes, Saturn comes up about two hours before the midnight hour (11 p.m. daylight saving time) in early June. (As a reminder, midnight in our usage means midway between sunset and sunrise.) By the month’s end, Saturn will rise around nightfall.

From temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Saturn rises at or around 8 p.m. in early June. By the month’s end, Saturn will rise by nightfall.

Watch for the waning moon to couple up with Saturn around June 18, as shown on the sky chart below. If you’re in just the right spot in South America, you can actually watch the moon occult (cover over) Saturn. Click here to find out more.

For the several days from June 16 to June 18, watch as the moon moves from Jupiter to Saturn. Read more.

Mars lurks low in the west at dusk/nightfall and follows the sun beneath the horizon shortly thereafter. Mars has faded into 2nd-magnitude brightness, which makes this world all the harder to spot. Given a dark sky and some diligent searching, you should be able to spot this world in your western sky at early evening.

Click here for recommended sky almanacs providing you with the setting times for Mars for your location.

Watch for the young crescent moon to shine in the vicinity of Mars for several evenings, centered on or near June 6. The moon’s proximity might provide you with your best opportunity to catch Mars in the evening sky for the rest of 2019. Day by day, this planet is slowly but surely fading, and sinking closer to the afterglow of sunset.

Starting on June 12 or thereabouts, Mercury will be close enough to Mars for the twosome to take stage in a single binocular field. After that, look for Mercury and Mars to occupy the same binocular field till nearly the end of the month. Watch for Mercury and Mars to snuggle up quite close together in the evening sky on June 17, 18 and 19, with Mercury passing a scant 0.2 degrees north of Mars on June 18, to present the closest conjunction of two planets in 2019.

Look westward for the close pairing of the planets Mercury and Mars on June 18, 2019. You may need binoculars to glimpse fainter Mars next to brighter Mercury. Read more.

What do we mean by bright planet? By bright planet, we mean any solar system planet that is easily visible without an optical aid and that has been watched by our ancestors since time immemorial. In their outward order from the sun, the five bright planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. These planets actually do appear bright in our sky. They are typically as bright as – or brighter than – the brightest stars. Plus, these relatively nearby worlds tend to shine with a steadier light than the distant, twinkling stars. You can spot them, and come to know them as faithful friends, if you try.

Skywatcher, by Predrag Agatonovic.

Bottom line: In June 2019, Jupiter beams from dusk till dawn, whereas Venus fleetingly shows itself in the east before sunrise. Saturn is out from mid-evening till dawn. Mercury and Mars lurk low in the west at dusk, and showcase the year’s closest conjunction of two planets on June 18, 2019. Click here for recommended almanacs; they can help you know when the planets rise and set in your sky.

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to EarthSky News by email

Visit EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze, and recommend a place we can all enjoy. Zoom out for worldwide map.

Help EarthSky keep going! Donate now.

Post your planet photos at EarthSky Community Photos

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/1YD00CF

Watch our guide to analysing the upcoming news below.

Watch our guide to analysing the upcoming news below.