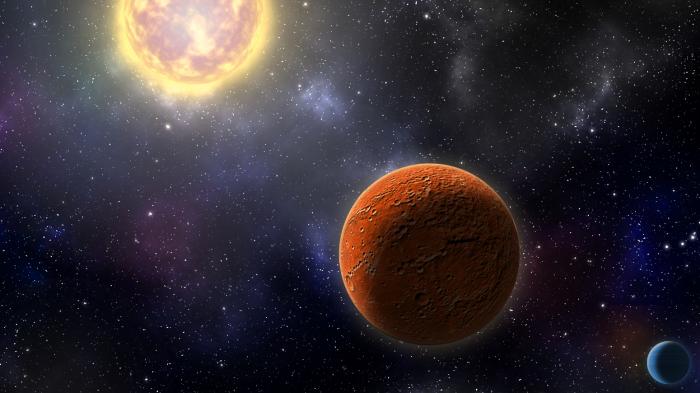

Artist’s concept of HD 21749c, the first Earth-sized exoplanet discovered by TESS. Image via Robin Dienel/Carnegie Institution for Science.

NASA’s newest exoplanet-hunting telescope, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), has now found its first Earth-sized world. It’s the smallest planet TESS has found yet in its still-young mission. Astronomers say it’s another exciting step towards finding worlds beyond our solar system that might be capable of supporting life.

The new peer-reviewed finding was published in Astrophysical Journal Letters on April 16, 2019, by astronomers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Carnegie Institution for Science.

The planet – labeled HD 21749c – orbits the star HD 21749, about 52 light-years from Earth. That is quite close, and it’s the kind of planet TESS was designed to help find. NASA’s last exoplanet-hunter – Kepler Space Telescope, which finished its mission last year – also found many smaller rocky planets of the type that most likely could be habitable. But, in contrast to TESS, Kepler focused on a small patch of the sky with relatively distant stars. The beauty of TESS is that it focuses on a large patch of sky and at closer stars. This new discovery by TESS demonstrates its ability to find small nearby planets and shows that the telescope is working as expected. As Diana Dragomir, lead author and TESS team member, explained:

For stars that are very close by and very bright, we expected to find up to a couple dozen Earth-sized planets. And here we are – this would be our first one, and it’s a milestone for TESS. It sets the path for finding smaller planets around even smaller stars, and those planets may potentially be habitable.

As Johanna Teske, an astronomer at Carnegie Institution for Science and second author on the new paper also said:

It’s so exciting that TESS, which launched just about a year ago, is already a game-changer in the planet-hunting business. The spacecraft surveys the sky and we collaborate with the TESS follow-up community to flag potentially interesting targets for additional observations using ground-based telescopes and instruments.

This particular planet, however, is probably not too friendly for life. It orbits very close to its star, completing an orbit in only 7.8 days. Its estimated surface temperature is 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 degrees Celsius). Astronomers want to find more planets that orbit their stars in the habitable zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water on their surfaces. A growing number have already been discovered, but, astronomers say, it’s still difficult to determine actual conditions on these worlds due to their great distances.

HD 21749c was found using the transit method, as the planet briefly blocked some of the light coming from the star when it passed in front of it. Eleven such transits were seen, and from that astronomers determined that the planet was about the same size as Earth and orbited its star every 7.8 days. Dragomir used a software code to look for this kind of transit, and found the periodic signals of both the Earth-sized planet and another planet reported earlier this year, known as HD 21749b.

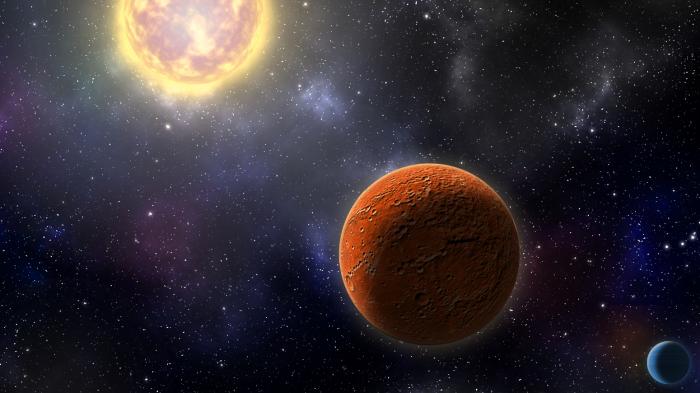

Artist’s concept of HD 21749b – a sister world to HD 21749c, in the same solar system – discovered earlier this year by TESS. The sister world is larger, a warm “sub-Neptune” with a longer 36-day orbit, and is 23 times Earth’s mass with a radius 2.7 times that of Earth. Image via NASA.

The Planet Finder Spectrograph (PFS) on the Magellan II telescope at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile was also used to help confirm the planetary nature of the TESS signal and to measure the mass of the newly discovered sub-Neptune. As Teske noted:

The Planet Finder Spectrograph is one of the only instruments in the Southern Hemisphere that can do these types of measurements. So, it will be a very important part of further characterizing the planets found by the TESS mission.

Astronomers hope that TESS will find at least 50 smaller planets – approximately the size of HD 21749b or smaller – during its mission. So far, it has discovered 10 planets smaller than Neptune, including pi Men b, twice the size of Earth with a six-day orbit; LHS 3844b, a hot, rocky world slightly larger than Earth that orbits its star in only 11 hours; and TOI 125b and c, two “sub-Neptunes” that orbit the same star, both within about a week. It is expected that TESS will discover many more similar worlds over the next months and years.

Planetary systems with one known smaller planet usually have more, astronomers have found, just like in our own solar system. Dragomir noted this also, saying:

We know these planets often come in families. So we searched all the data again, and this small signal came up.

TESS is already finding its share of new exoplanets orbiting nearby stars, continuing on from the Kepler mission, which ended last year. Image via Goddard Space Flight Center (edited by MIT News).

One big advantage that TESS has compared to Kepler is that because the planets it finds orbit closer stars, those planets will be easier targets for follow-up observations from other telescopes. These other telescopes could examine the atmospheres of the newly-discovered worlds. This is, of course, of particular significance for rocky planets similar to Earth, some of which could be habitable. According to Dragomir:

Because TESS monitors stars that are much closer and brighter, we can measure the mass of this planet in the very near future, whereas for Kepler’s Earth-sized planets, that was out of the question. So this new TESS discovery could lead to the first mass measurement of an Earth-sized planet. And we’re excited about what that mass could be. Will it be Earth’s mass? Or heavier? We don’t really know.

According to astronomer Sharon Wang at Carnegie Institution for Science:

Measuring the exact mass and composition of such a small planet will be challenging, but important for comparing HD 21749c to Earth. Carnegie’s PFS team is continuing to collect data on this object with this goal in mind.

This first Earth-sized world that TESS has found may not be the most ideal in terms of the possibility of life, but it shows that the mission is proceeding as hoped, and that, as expected, planets are abundant around stars closer to the sun as well as those farther away. Based on previous data from Kepler, it is now thought that almost every star in our galaxy has at least one planet, and many with multiple planets, just like our solar system – in other words, there are billions of planets in our galaxy alone. TESS will now be able to study some of those worlds that are closer to home, bringing us even closer to finding the holy grail of exoplanetary research – another living world.

Bottom line: The discovery of HD 21749c – an Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting a nearby star – is exciting, and should be just the first of many more to come from the TESS mission.

Source: TESS delivers its first Earth-sized planet and a warm sub-Neptune

Via MIT News and Carnegie Science

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2ZBUQyb

Artist’s concept of HD 21749c, the first Earth-sized exoplanet discovered by TESS. Image via Robin Dienel/Carnegie Institution for Science.

NASA’s newest exoplanet-hunting telescope, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), has now found its first Earth-sized world. It’s the smallest planet TESS has found yet in its still-young mission. Astronomers say it’s another exciting step towards finding worlds beyond our solar system that might be capable of supporting life.

The new peer-reviewed finding was published in Astrophysical Journal Letters on April 16, 2019, by astronomers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Carnegie Institution for Science.

The planet – labeled HD 21749c – orbits the star HD 21749, about 52 light-years from Earth. That is quite close, and it’s the kind of planet TESS was designed to help find. NASA’s last exoplanet-hunter – Kepler Space Telescope, which finished its mission last year – also found many smaller rocky planets of the type that most likely could be habitable. But, in contrast to TESS, Kepler focused on a small patch of the sky with relatively distant stars. The beauty of TESS is that it focuses on a large patch of sky and at closer stars. This new discovery by TESS demonstrates its ability to find small nearby planets and shows that the telescope is working as expected. As Diana Dragomir, lead author and TESS team member, explained:

For stars that are very close by and very bright, we expected to find up to a couple dozen Earth-sized planets. And here we are – this would be our first one, and it’s a milestone for TESS. It sets the path for finding smaller planets around even smaller stars, and those planets may potentially be habitable.

As Johanna Teske, an astronomer at Carnegie Institution for Science and second author on the new paper also said:

It’s so exciting that TESS, which launched just about a year ago, is already a game-changer in the planet-hunting business. The spacecraft surveys the sky and we collaborate with the TESS follow-up community to flag potentially interesting targets for additional observations using ground-based telescopes and instruments.

This particular planet, however, is probably not too friendly for life. It orbits very close to its star, completing an orbit in only 7.8 days. Its estimated surface temperature is 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 degrees Celsius). Astronomers want to find more planets that orbit their stars in the habitable zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water on their surfaces. A growing number have already been discovered, but, astronomers say, it’s still difficult to determine actual conditions on these worlds due to their great distances.

HD 21749c was found using the transit method, as the planet briefly blocked some of the light coming from the star when it passed in front of it. Eleven such transits were seen, and from that astronomers determined that the planet was about the same size as Earth and orbited its star every 7.8 days. Dragomir used a software code to look for this kind of transit, and found the periodic signals of both the Earth-sized planet and another planet reported earlier this year, known as HD 21749b.

Artist’s concept of HD 21749b – a sister world to HD 21749c, in the same solar system – discovered earlier this year by TESS. The sister world is larger, a warm “sub-Neptune” with a longer 36-day orbit, and is 23 times Earth’s mass with a radius 2.7 times that of Earth. Image via NASA.

The Planet Finder Spectrograph (PFS) on the Magellan II telescope at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile was also used to help confirm the planetary nature of the TESS signal and to measure the mass of the newly discovered sub-Neptune. As Teske noted:

The Planet Finder Spectrograph is one of the only instruments in the Southern Hemisphere that can do these types of measurements. So, it will be a very important part of further characterizing the planets found by the TESS mission.

Astronomers hope that TESS will find at least 50 smaller planets – approximately the size of HD 21749b or smaller – during its mission. So far, it has discovered 10 planets smaller than Neptune, including pi Men b, twice the size of Earth with a six-day orbit; LHS 3844b, a hot, rocky world slightly larger than Earth that orbits its star in only 11 hours; and TOI 125b and c, two “sub-Neptunes” that orbit the same star, both within about a week. It is expected that TESS will discover many more similar worlds over the next months and years.

Planetary systems with one known smaller planet usually have more, astronomers have found, just like in our own solar system. Dragomir noted this also, saying:

We know these planets often come in families. So we searched all the data again, and this small signal came up.

TESS is already finding its share of new exoplanets orbiting nearby stars, continuing on from the Kepler mission, which ended last year. Image via Goddard Space Flight Center (edited by MIT News).

One big advantage that TESS has compared to Kepler is that because the planets it finds orbit closer stars, those planets will be easier targets for follow-up observations from other telescopes. These other telescopes could examine the atmospheres of the newly-discovered worlds. This is, of course, of particular significance for rocky planets similar to Earth, some of which could be habitable. According to Dragomir:

Because TESS monitors stars that are much closer and brighter, we can measure the mass of this planet in the very near future, whereas for Kepler’s Earth-sized planets, that was out of the question. So this new TESS discovery could lead to the first mass measurement of an Earth-sized planet. And we’re excited about what that mass could be. Will it be Earth’s mass? Or heavier? We don’t really know.

According to astronomer Sharon Wang at Carnegie Institution for Science:

Measuring the exact mass and composition of such a small planet will be challenging, but important for comparing HD 21749c to Earth. Carnegie’s PFS team is continuing to collect data on this object with this goal in mind.

This first Earth-sized world that TESS has found may not be the most ideal in terms of the possibility of life, but it shows that the mission is proceeding as hoped, and that, as expected, planets are abundant around stars closer to the sun as well as those farther away. Based on previous data from Kepler, it is now thought that almost every star in our galaxy has at least one planet, and many with multiple planets, just like our solar system – in other words, there are billions of planets in our galaxy alone. TESS will now be able to study some of those worlds that are closer to home, bringing us even closer to finding the holy grail of exoplanetary research – another living world.

Bottom line: The discovery of HD 21749c – an Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting a nearby star – is exciting, and should be just the first of many more to come from the TESS mission.

Source: TESS delivers its first Earth-sized planet and a warm sub-Neptune

Via MIT News and Carnegie Science

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2ZBUQyb