This was was published originally at the Virtual Telescope Project and appears here with permission.

I have been thinking for decades about seeing and hopefully imagining all eight planets of our solar system in one night, from sunset to dawn. And I did it on the night of August 28-29, 2018, in a very special way: I imaged all of them from Rome, above the amazing monuments of the Eternal City. It was hard, but it was fun!

Spying the entire planetary family in one night is not straightforward. You need all the planets to be far enough from the sun, away from its intense light, but this happens from time to time. In 2016, I succeeded in observing and imaging the five bright planets – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn – at a glance, when they offered a great view . Again, earlier this month, I could capture four of the five bright planets crossing the starry catwalk above Rome.

Of course, the Earth in the foreground qualified as a planet, too.

Since Pluto got demoted from being considered a planet in 2006, the remaining planets, the two faint ones – Uranus and Neptune – can be seen even with a very modest binocular. These two planets – which move slowly around the sun, and so slowly in front of the star background – have been for some years among the stars of Northern Hemisphere autumn, a season we are approaching. Uranus and Neptune are now up in the middle of the night.

Thus the official, current eight planets of our solar system are available for a wonderful grand tour, if you carefully choose the right moment, weather included.

And these days are just perfect!

With Venus leaving the evening sky pretty soon, I had to wait for Mercury to show at dawn. It is there now. I was ready to go, but in a special manner: instead of observing them in a plain way, I wanted to image them from Rome (not an easy location for Uranus and Neptune, being faint enough and difficult to see under severe light pollution), framing each with a monument of the Eternal City.

Such a solar system imaging marathon was never done with this idea in mind, to my knowledge.

I prepared my imaging gear, consisting of two Canon 5DmIV DSLR bodies and two lenses: a Canon EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM and a Canon EF 70-200mm f/2.8L IS II USM. Of course, I had a sturdy tripod to put all this on it.

As Uranus and especially Neptune are faint to see from a big city, I had to carefully select the imaging location and the monuments to include in their pictures. I studied this in depth, also considering my long-time experience in imaging the sky from the city, selecting some very suitable places, both for the imaging conditions and the presence of an illustrious monument. With everything set and ready to go, I decided to go out on the night of August 28-29, beginning this cosmic tour. The moon was also going to show, adding to the planetary family in a nice way.

Venus requires immediate action soon after sunset, as it leaves the sky soon after sunset.

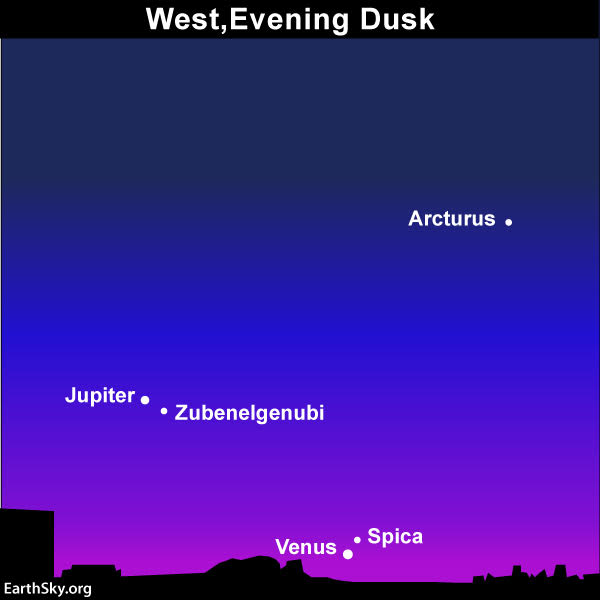

Jupiter is not far from Venus, providing a great sight: two of the brightest celestial objects at a glance. My image of both of them, above the Synagogue of Rome, is at the top of this post. First two planets secured! Easily and safely, I would say.

Then, I changed my location, bringing with me the heavy payload I mentioned above. I understand why people looked at me in such a curious way.

Next stop was the Roman Forum, to grab Saturn and Mars. I managed to include the Temple of Saturn (how appropriate!) and the Temple of Vespasian and Titus in such a capture. Seeing this area at night is always breathtaking and having planets and stars above is mind-blowing. In a few minutes, under a dozen curious eyes, I was ready and started imaging. The image is below; I hope you like it, too.

Of course, I enjoyed all this with my very own eyes: technology is great, but as humans we need to feed our five senses with beauty. Time to leave for another planet!

The third stop was planned to capture Neptune, the farthest of the eight planets, hence the faintest. For the most difficult object, I wanted a legendary monument and luckily in Rome we have the immortal Colosseum. It was the gem of Rome I wanted in my picture of Neptune, despite that the planet was going to be visible as a mere dot of very faint light. I took 10 images, then I averaged them to increase the quality of the weak signal of Neptune and I must admit it worked very well.

Below you can check and judge yourself.

But I knew someone was going to enter the scenery and join the trip …

On the left of the picture above, you can see some glare. That is the moon rising behind the Basilica of Maxentius. Switching to my other camera, with a longer lens and, waiting for a while to have it perfectly placed, the moon joined the tour in a great way.

Once done with the moon, I had to wait for Uranus to climb the sky, so I took a little rest. It was really needed, I cannot tell you how much I walked. I remembered I had no dinner, so I did a ride to home to get some energy back, later going out again, under the stars.

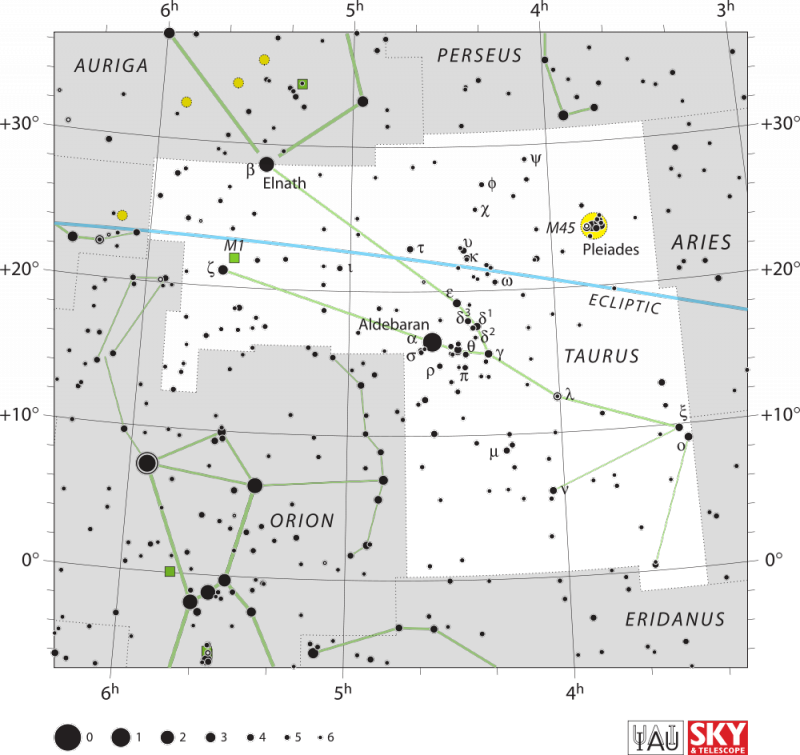

The location for Uranus was, again, the Roman Forum, where I studied this time a vertical image: I carefully included the small, but wonderful Pleiades open cluster, visible about midway up on the left side of the image as a very small dipper.

Uranus is marked and labelled for your convenience. This time, I averaged three images.

Uranus is discreetly shining above the Roman Forum, with the Pleiades star cluster – a tiny dipper – visible midway up on the left. August 28, 2018. Photo via Virtual Telescope Project.

Then, the only missing planet was Mercury. It was going to rise at dawn, so I decided to go home and have a couple of hours of sleeping. When the clock alarm shouted it was time to move, I quickly left home and drove to the Janiculum Hill, facing east, where I had to wait for Mercury. I was alone there, the temperature was 19 Celsius degrees (66 degrees Fahrenheit) … Summer will not last forever.

I started imaging when Mercury was just a few degrees above the horizon, while the twilight already started and I could see the planet in my images first, then I could see it with the eye alone.

The panorama of Rome from there was honestly superb.

At this point the grand tour was over. I was very tired, but it was hard to leave, after such a journey. I traveled for billions of kilometers, back and forth through our solar system, spotting all its eight planets (Earth included, as the foreground in my images!) and the moon above some of the most precious monuments and symbols of our culture and history.

I hope this long report was able to bring to you my experience and feelings and that your time used to read it was well spent. I can say that living this experience was amazing, one of those things leaving great memories and feeding our love for the Cosmos and Beauty.

My friend Bob King wrote a nice article about seeing the eight planets, by the way. Check it out here!

You have a few days left to do the same journey, go out and try. Good luck!

Bottom line: All eight planets of our solar system, captured in one night, above the ancient monuments of Rome!

Help support the Virtual Telescope Project

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2LQJBd0

This was was published originally at the Virtual Telescope Project and appears here with permission.

I have been thinking for decades about seeing and hopefully imagining all eight planets of our solar system in one night, from sunset to dawn. And I did it on the night of August 28-29, 2018, in a very special way: I imaged all of them from Rome, above the amazing monuments of the Eternal City. It was hard, but it was fun!

Spying the entire planetary family in one night is not straightforward. You need all the planets to be far enough from the sun, away from its intense light, but this happens from time to time. In 2016, I succeeded in observing and imaging the five bright planets – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn – at a glance, when they offered a great view . Again, earlier this month, I could capture four of the five bright planets crossing the starry catwalk above Rome.

Of course, the Earth in the foreground qualified as a planet, too.

Since Pluto got demoted from being considered a planet in 2006, the remaining planets, the two faint ones – Uranus and Neptune – can be seen even with a very modest binocular. These two planets – which move slowly around the sun, and so slowly in front of the star background – have been for some years among the stars of Northern Hemisphere autumn, a season we are approaching. Uranus and Neptune are now up in the middle of the night.

Thus the official, current eight planets of our solar system are available for a wonderful grand tour, if you carefully choose the right moment, weather included.

And these days are just perfect!

With Venus leaving the evening sky pretty soon, I had to wait for Mercury to show at dawn. It is there now. I was ready to go, but in a special manner: instead of observing them in a plain way, I wanted to image them from Rome (not an easy location for Uranus and Neptune, being faint enough and difficult to see under severe light pollution), framing each with a monument of the Eternal City.

Such a solar system imaging marathon was never done with this idea in mind, to my knowledge.

I prepared my imaging gear, consisting of two Canon 5DmIV DSLR bodies and two lenses: a Canon EF 24-70mm f/2.8L II USM and a Canon EF 70-200mm f/2.8L IS II USM. Of course, I had a sturdy tripod to put all this on it.

As Uranus and especially Neptune are faint to see from a big city, I had to carefully select the imaging location and the monuments to include in their pictures. I studied this in depth, also considering my long-time experience in imaging the sky from the city, selecting some very suitable places, both for the imaging conditions and the presence of an illustrious monument. With everything set and ready to go, I decided to go out on the night of August 28-29, beginning this cosmic tour. The moon was also going to show, adding to the planetary family in a nice way.

Venus requires immediate action soon after sunset, as it leaves the sky soon after sunset.

Jupiter is not far from Venus, providing a great sight: two of the brightest celestial objects at a glance. My image of both of them, above the Synagogue of Rome, is at the top of this post. First two planets secured! Easily and safely, I would say.

Then, I changed my location, bringing with me the heavy payload I mentioned above. I understand why people looked at me in such a curious way.

Next stop was the Roman Forum, to grab Saturn and Mars. I managed to include the Temple of Saturn (how appropriate!) and the Temple of Vespasian and Titus in such a capture. Seeing this area at night is always breathtaking and having planets and stars above is mind-blowing. In a few minutes, under a dozen curious eyes, I was ready and started imaging. The image is below; I hope you like it, too.

Of course, I enjoyed all this with my very own eyes: technology is great, but as humans we need to feed our five senses with beauty. Time to leave for another planet!

The third stop was planned to capture Neptune, the farthest of the eight planets, hence the faintest. For the most difficult object, I wanted a legendary monument and luckily in Rome we have the immortal Colosseum. It was the gem of Rome I wanted in my picture of Neptune, despite that the planet was going to be visible as a mere dot of very faint light. I took 10 images, then I averaged them to increase the quality of the weak signal of Neptune and I must admit it worked very well.

Below you can check and judge yourself.

But I knew someone was going to enter the scenery and join the trip …

On the left of the picture above, you can see some glare. That is the moon rising behind the Basilica of Maxentius. Switching to my other camera, with a longer lens and, waiting for a while to have it perfectly placed, the moon joined the tour in a great way.

Once done with the moon, I had to wait for Uranus to climb the sky, so I took a little rest. It was really needed, I cannot tell you how much I walked. I remembered I had no dinner, so I did a ride to home to get some energy back, later going out again, under the stars.

The location for Uranus was, again, the Roman Forum, where I studied this time a vertical image: I carefully included the small, but wonderful Pleiades open cluster, visible about midway up on the left side of the image as a very small dipper.

Uranus is marked and labelled for your convenience. This time, I averaged three images.

Uranus is discreetly shining above the Roman Forum, with the Pleiades star cluster – a tiny dipper – visible midway up on the left. August 28, 2018. Photo via Virtual Telescope Project.

Then, the only missing planet was Mercury. It was going to rise at dawn, so I decided to go home and have a couple of hours of sleeping. When the clock alarm shouted it was time to move, I quickly left home and drove to the Janiculum Hill, facing east, where I had to wait for Mercury. I was alone there, the temperature was 19 Celsius degrees (66 degrees Fahrenheit) … Summer will not last forever.

I started imaging when Mercury was just a few degrees above the horizon, while the twilight already started and I could see the planet in my images first, then I could see it with the eye alone.

The panorama of Rome from there was honestly superb.

At this point the grand tour was over. I was very tired, but it was hard to leave, after such a journey. I traveled for billions of kilometers, back and forth through our solar system, spotting all its eight planets (Earth included, as the foreground in my images!) and the moon above some of the most precious monuments and symbols of our culture and history.

I hope this long report was able to bring to you my experience and feelings and that your time used to read it was well spent. I can say that living this experience was amazing, one of those things leaving great memories and feeding our love for the Cosmos and Beauty.

My friend Bob King wrote a nice article about seeing the eight planets, by the way. Check it out here!

You have a few days left to do the same journey, go out and try. Good luck!

Bottom line: All eight planets of our solar system, captured in one night, above the ancient monuments of Rome!

Help support the Virtual Telescope Project

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2LQJBd0