By Laura Haynes, University of Connecticut

Every year, from 5 to 20 percent of the people in the United States will become infected with influenza virus. An average of 200,000 of these people will require hospitalization and up to 50,000 will die. Older folks over the age of 65 are especially susceptible to influenza infection, since the immune system becomes weaker with age. In addition, older folks are also more susceptible to long-term disability following influenza infection, especially if they are hospitalized.

We all know the symptoms of influenza infection include fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, headaches and fatigue. But just what causes all the havoc? What is going on in your body as you fight the flu?

I am a researcher who specializes in immunology at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, and my laboratory focuses on how influenza infection affects the body and how our bodies combat the virus. It’s interesting to note that many of the body’s defenses that attack the virus also cause many of the symptoms associated with the flu.

A flu patient at ProMedica Toledo Hospital in Toledo, Ohio on January 8, 2018. Image via AP Photo/Tony Dejak

How the flu works its way into your body

Influenza virus causes an infection in the respiratory tract, or nose, throat and lungs. The virus is inhaled or transmitted, usually via your fingers, to the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose or eyes. It then travels down the respiratory tract and binds to epithelial cells lining the lung airways via specific molecules on the cell surface. Once inside the cells, the virus hijacks the protein manufacturing machinery of the cell to generate its own viral proteins and create more viral particles. Once mature viral particles are produced, they are released from the cell and can then go on to invade adjacent cells.

While this process causes some lung injury, most of the symptoms of the flu are actually caused by the immune response to the virus. The initial immune response involves cells of the body’s innate immune system, such as macrophages and neutrophils. These cells express receptors that are able to sense the presence of the virus. They then sound the alarm by producing small hormone-like molecules called cytokines and chemokines. These alert the body that an infection has been established.

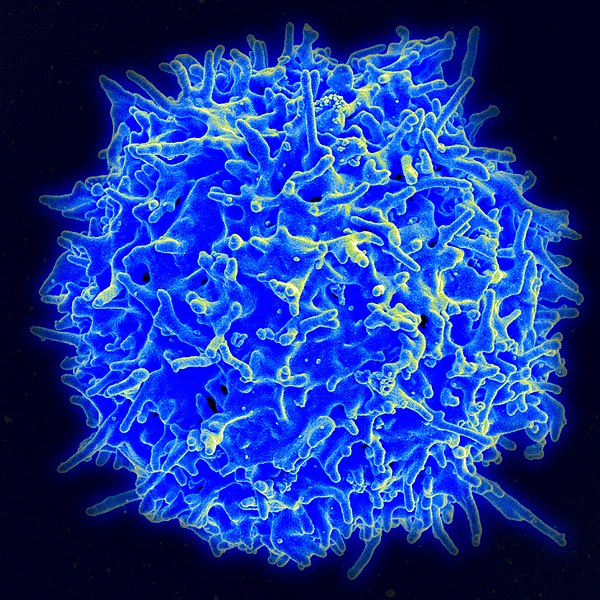

Cytokines orchestrate other components of the immune system to appropriately fight the invading virus, while chemokines direct these components to the location of infection. One of the types of cells called into action are T lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell that fights infection. Sometimes, they are even called “soldier” cells. When T cells specifically recognize influenza virus proteins, they then begin to proliferate in the lymph nodes around the lungs and throat. This causes swelling and pain in these lymph nodes.

After a few days, these T cells move to the lungs and begin to kill the virus-infected cells. This process creates a great deal of lung damage similar to bronchitis, which can worsen existing lung disease and make breathing difficult. In addition, the buildup of mucus in the lungs, as a result of this immune response to infection, induces coughing as a reflex to try to clear the airways. Normally, this damage triggered by arrival of T cells in the lungs is reversible in a healthy person, but when it advances, it is bad news and can lead to death.

The proper functioning of influenza-specific T cells is critical for efficient clearance of the virus from the lungs. When T cell function declines, such as with increasing age or during use of immunosuppressive drugs, viral clearance is delayed. This results in a prolonged infection and greater lung damage. This can also set the stage for complications including secondary bacterial pneumonia, which can often be deadly.

Why your head hurts so much

While the influenza virus is wholly contained in the lungs under normal circumstances, several symptoms of influenza are systemic, including fever, headache, fatigue and muscle aches. In order to properly combat influenza infection, the cytokines and chemokines produced by the innate immune cells in the lungs become systemic – that is, they enter the bloodstream, and contribute to these systemic symptoms. When this happens, a cascade of complicating biological events occurs.

One of the things that happens is that Interleukin-1, an inflammatory type of cytokine, is activated. Interleukin-1 is important for developing the killer T cell response against the virus, but it also affects the part of the brain in the hypothalamus that regulates body temperature, resulting in fever and headaches.

Another important cytokine that fights influenza infection is something called “tumor necrosis factor alpha.” This cytokine can have direct antiviral effects in the lungs, and that’s good. But it can also cause fever and appetite loss, fatigue and weakness during influenza and other types of infection.

Why your muscles ache

Our research has also uncovered another aspect of how influenza infection affects our bodies.

It is well-known that muscle aches and weakness are prominent symptoms of influenza infection. Our study in an animal model found that influenza infection leads to an increase in the expression of muscle-degrading genes and a decrease in expression of muscle-building genes in skeletal muscles in the legs.

Functionally, influenza infection also hinders walking and leg strength. Importantly, in young individuals, these effects are transient and return to normal once the infection was cleared.

In contrast, these effects can linger significantly longer in older individuals. This is important, since a decrease in leg stability and strength could result in older folks being more prone to falls during recovery from influenza infection. It could also result in long-term disability and lead to the need for a cane or walker, limiting mobility and independence.

Researchers in my lab think that this impact of influenza infection on muscles is another unintended consequence of the immune response to the virus. We are currently working to determine what specific factors produced during the immune response are responsible for this and if we can find a way to prevent it.

Thus, while you feel miserable when you have an influenza infection, you can rest assured that it is because your body is fighting hard. It’s combating the spread of the virus in your lungs and killing infected cells.

Thus, while you feel miserable when you have an influenza infection, you can rest assured that it is because your body is fighting hard. It’s combating the spread of the virus in your lungs and killing infected cells.

Laura Haynes, Professor of Immunology, University of Connecticut

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Bottom line: An immunologist explains what’s going on inside your body when you have the flu.

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/2F8STPa

By Laura Haynes, University of Connecticut

Every year, from 5 to 20 percent of the people in the United States will become infected with influenza virus. An average of 200,000 of these people will require hospitalization and up to 50,000 will die. Older folks over the age of 65 are especially susceptible to influenza infection, since the immune system becomes weaker with age. In addition, older folks are also more susceptible to long-term disability following influenza infection, especially if they are hospitalized.

We all know the symptoms of influenza infection include fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, headaches and fatigue. But just what causes all the havoc? What is going on in your body as you fight the flu?

I am a researcher who specializes in immunology at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, and my laboratory focuses on how influenza infection affects the body and how our bodies combat the virus. It’s interesting to note that many of the body’s defenses that attack the virus also cause many of the symptoms associated with the flu.

A flu patient at ProMedica Toledo Hospital in Toledo, Ohio on January 8, 2018. Image via AP Photo/Tony Dejak

How the flu works its way into your body

Influenza virus causes an infection in the respiratory tract, or nose, throat and lungs. The virus is inhaled or transmitted, usually via your fingers, to the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose or eyes. It then travels down the respiratory tract and binds to epithelial cells lining the lung airways via specific molecules on the cell surface. Once inside the cells, the virus hijacks the protein manufacturing machinery of the cell to generate its own viral proteins and create more viral particles. Once mature viral particles are produced, they are released from the cell and can then go on to invade adjacent cells.

While this process causes some lung injury, most of the symptoms of the flu are actually caused by the immune response to the virus. The initial immune response involves cells of the body’s innate immune system, such as macrophages and neutrophils. These cells express receptors that are able to sense the presence of the virus. They then sound the alarm by producing small hormone-like molecules called cytokines and chemokines. These alert the body that an infection has been established.

Cytokines orchestrate other components of the immune system to appropriately fight the invading virus, while chemokines direct these components to the location of infection. One of the types of cells called into action are T lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell that fights infection. Sometimes, they are even called “soldier” cells. When T cells specifically recognize influenza virus proteins, they then begin to proliferate in the lymph nodes around the lungs and throat. This causes swelling and pain in these lymph nodes.

After a few days, these T cells move to the lungs and begin to kill the virus-infected cells. This process creates a great deal of lung damage similar to bronchitis, which can worsen existing lung disease and make breathing difficult. In addition, the buildup of mucus in the lungs, as a result of this immune response to infection, induces coughing as a reflex to try to clear the airways. Normally, this damage triggered by arrival of T cells in the lungs is reversible in a healthy person, but when it advances, it is bad news and can lead to death.

The proper functioning of influenza-specific T cells is critical for efficient clearance of the virus from the lungs. When T cell function declines, such as with increasing age or during use of immunosuppressive drugs, viral clearance is delayed. This results in a prolonged infection and greater lung damage. This can also set the stage for complications including secondary bacterial pneumonia, which can often be deadly.

Why your head hurts so much

While the influenza virus is wholly contained in the lungs under normal circumstances, several symptoms of influenza are systemic, including fever, headache, fatigue and muscle aches. In order to properly combat influenza infection, the cytokines and chemokines produced by the innate immune cells in the lungs become systemic – that is, they enter the bloodstream, and contribute to these systemic symptoms. When this happens, a cascade of complicating biological events occurs.

One of the things that happens is that Interleukin-1, an inflammatory type of cytokine, is activated. Interleukin-1 is important for developing the killer T cell response against the virus, but it also affects the part of the brain in the hypothalamus that regulates body temperature, resulting in fever and headaches.

Another important cytokine that fights influenza infection is something called “tumor necrosis factor alpha.” This cytokine can have direct antiviral effects in the lungs, and that’s good. But it can also cause fever and appetite loss, fatigue and weakness during influenza and other types of infection.

Why your muscles ache

Our research has also uncovered another aspect of how influenza infection affects our bodies.

It is well-known that muscle aches and weakness are prominent symptoms of influenza infection. Our study in an animal model found that influenza infection leads to an increase in the expression of muscle-degrading genes and a decrease in expression of muscle-building genes in skeletal muscles in the legs.

Functionally, influenza infection also hinders walking and leg strength. Importantly, in young individuals, these effects are transient and return to normal once the infection was cleared.

In contrast, these effects can linger significantly longer in older individuals. This is important, since a decrease in leg stability and strength could result in older folks being more prone to falls during recovery from influenza infection. It could also result in long-term disability and lead to the need for a cane or walker, limiting mobility and independence.

Researchers in my lab think that this impact of influenza infection on muscles is another unintended consequence of the immune response to the virus. We are currently working to determine what specific factors produced during the immune response are responsible for this and if we can find a way to prevent it.

Thus, while you feel miserable when you have an influenza infection, you can rest assured that it is because your body is fighting hard. It’s combating the spread of the virus in your lungs and killing infected cells.

Thus, while you feel miserable when you have an influenza infection, you can rest assured that it is because your body is fighting hard. It’s combating the spread of the virus in your lungs and killing infected cells.

Laura Haynes, Professor of Immunology, University of Connecticut

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Bottom line: An immunologist explains what’s going on inside your body when you have the flu.

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/2F8STPa