Gregor in Switzerland submitted this composite image from the morning of December 15, 2015.

Your goal: to observe a meteor shower. You read an article about an upcoming meteor shower, and you want to see as many meteors as possible. You want to see the sky rain meteors like hailstones at an apocalyptic rate. You want exploding fireballs, peals of meteoric thunder, celestial mayhem. Well … that likely won’t happen. Meteor showers, for the most part, aren’t like a shower of rain, and a meteor rate of one a minute is a very, very good shower. Meteor showers are wonderful natural phenomena, a chance to commune with the outdoors and see something beautiful. How can you optimize your chances for seeing the most meteors? Follow the links below for EarthSky’s top 10 tips for meteor-watchers!

1.Be sure you know which days the shower will peak.

2. Find out the time of the shower’s peak in your time zone.

3. Watch on the nights around the peak, too.

4. Understanding the shower’s radiant point can help.

5. Find out the shower’s expected rate, or number of meteors per hour.

6. You must be aware of the phase of the moon.

7. Dress warmly.

8. Bring along that thermos of hot coffee or tea.

9. Bring a blanket or lawn chair.

10. Relax and enjoy the night sky.

Early Geminid meteor caught on the night of December 6, 2015, by Barry Simmons in Lake Martin, Alabama.

1. Be sure you know which days the shower will peak. Meteor showers happen over many days, as Earth encounters a wide stream of icy particles in space: debris left behind by a comet. The peak is just what it implies. It’s a point in time when Earth is expected to encounter the greatest number of particles from a particular meteor stream. You can find peak dates nowadays easily on the Internet. Try EarthSky’s meteor guide for 2016. Be aware that most, but not all, meteor showers are best after midnight.

And here’s the catch …

The peak of the shower comes at the same time for all of us on Earth. Meanwhile, our clocks are saying different times. So …

2. Find out the time of the shower’s peak in your timezone. You don’t need to watch exactly at the peak time. But it can help you decide which night is absolutely best for you.

Different sources might list different times for the peak of a meteor shower. In that case, go with a source you trust. Here at EarthSky, we trust the Observer’s Handbook from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Predictions are not always spot on, and the peak typically stretches over a day or so.

See how it works?

The time of the peak will nearly always be given in UTC. That stands for Coordinated Universal Time, and it’s the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. Learn to translate UTC to your time zone in this article.

3. Watch on the nights around the peak, too. If you miss a shower’s peak, you might not see as many meteors. But don’t let that discourage you! As we’ve mentioned before, predictions for meteor shower peaks are not always right on the money. It’s possible to see very nice meteor displays hours before or after the published peak.

For example, who can forget the famous 1998 Leonid meteor shower? The predicted peak favored observers in Europe, and yet those of us in the states were nevertheless treated to wonderful displays of Leonids on the nights before and after the predicted peak.

Just remember, meteor showers are part of nature. They often defy prediction.

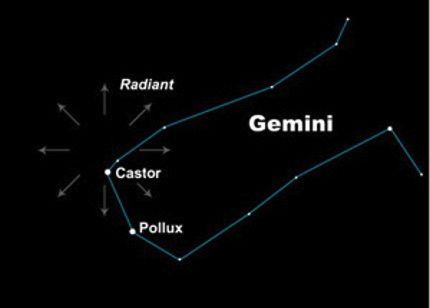

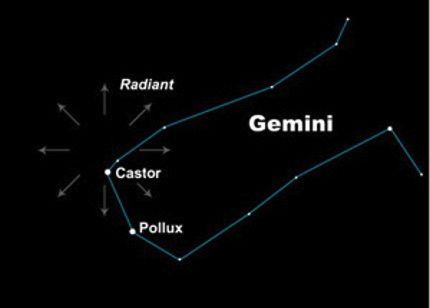

The Geminid meteors radiate from near the star Castor in Gemini.

4. Understanding the shower’s radiant point can help. A meteor shower’s radiant point is that point in the sky from which the meteors will appear to radiate. Some people seem to think they have to be able to identify the radiant point in order to be able to watch the shower, but that is a serious misconception.

You can see meteors shoot up from the horizon before a shower’s radiant has even risen into the sky.

Here’s the power of the radiant point. Once it has risen into your sky, you’ll see more meteors. When it’s at its highest overhead – assuming you’re watching at a time when the shower has been producing meteors steadily over many hours – you’ll see the most meteors.

So find out the radiant point’s rising time. It can help you pinpoint the best time of night to watch the shower.

Randy Baumhover captured this image at Meyers Creek Beach on the Oregon coast.

5. Find out the shower’s expected rate, or number of meteors per hour. Here we touch on a topic that often leads to some bad feelings, especially among novice meteor watchers. Tables of meteor showers almost always list what is known as the zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) for each shower.

The ZHR is the number of meteors you’ll see if you’re watching in a very dark sky, when the radiant overhead, when the shower is at its peak.

In other words, the ZHR represents the number of meteors you might see per hour given the very best observing conditions during the shower’s maximum.

Now let’s apply this term to a real world example. Let’s say the December Geminid meteor shower has a ZHR of 120 meteors per hour. That doesn’t mean you’ll see 120 meteors per hour, but it does mean you might if you’re watching on a peak night in a dark sky, when the radiant is highest.

If the peak occurs when it’s still daylight at your location, if most of the meteors are predominantly faint, if a bright moon is out , or if you’re located in a light-polluted area, the total number of meteors you see will be considerably reduced.

Also know that most meteor showers have bursts of activity, with lulls in between. That’s why you should plan to watch the shower, from a dark location, for at least an hour or more. Several hours per night for several nights will give you the best chance of seeing the best show.

And that brings us to one of the most important factors of all for meteor-watchers…

6. You must be aware of the phase of the moon. If the moon is at a quarter phase or greater, you’re going to miss meteors, even if your skies are otherwise dark. It’s okay if the moon sets before the radiant rises, because the Earth blocks the moon’s light from the sky. But nothing dampens the display of a meteor shower more effectively than the presence of a bright moon.

Now you’re almost ready. Just a few final tips.

7. Dress warmly. The nights can be cool or cold, even during the spring and summer months.

8. Bring along that thermos of hot coffee or tea. It’ll be your friend at 3 a.m.

9. Bring a blanket or lawn chair for reclining comfortably while looking up at the sky. If you’re observing with a friend, set your chairs out back to back, and look at different parts of the sky. Then when one of you sees a meteors, he or she can call out “meteor,” and everyone can turn and look.

10. Relax and enjoy the night sky. Not every meteor shower is a winner. Sometimes, you may come away from a shower seeing only one meteor. But consider this. If that one meteor is a bright one that takes a slow path across a starry night sky … it’ll be worth it.

To be really successful at observing any meteor shower, you need to get into a kind of Zen state, waiting and expecting the meteors to come to you if you place yourself in the position to see them. Or forget the Zen state, and let yourself be guided by this old meteor watcher’s motto:

You might see a lot or you might not see many, but if you stay in the house, you won’t see any.

By the way, if you’re interested in learning more about meteor showers, or want to contribute meteor counts and brightness estimations, contact the following organizations: The American Meteor Society and the International Meteor Organization. Both provided the latest predictions as well as information to guide you in serious meteor observing.

View larger. | Early Geminid fireball caught on December 2, 2015 at 10:34 p.m. from the Tucson, Arizona foothills. Photo via Eliot Herman.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: How to watch a meteor shower. Tips for beginners.

EarthSky’s meteor guide for 2016

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/1lsGYLX

Gregor in Switzerland submitted this composite image from the morning of December 15, 2015.

Your goal: to observe a meteor shower. You read an article about an upcoming meteor shower, and you want to see as many meteors as possible. You want to see the sky rain meteors like hailstones at an apocalyptic rate. You want exploding fireballs, peals of meteoric thunder, celestial mayhem. Well … that likely won’t happen. Meteor showers, for the most part, aren’t like a shower of rain, and a meteor rate of one a minute is a very, very good shower. Meteor showers are wonderful natural phenomena, a chance to commune with the outdoors and see something beautiful. How can you optimize your chances for seeing the most meteors? Follow the links below for EarthSky’s top 10 tips for meteor-watchers!

1.Be sure you know which days the shower will peak.

2. Find out the time of the shower’s peak in your time zone.

3. Watch on the nights around the peak, too.

4. Understanding the shower’s radiant point can help.

5. Find out the shower’s expected rate, or number of meteors per hour.

6. You must be aware of the phase of the moon.

7. Dress warmly.

8. Bring along that thermos of hot coffee or tea.

9. Bring a blanket or lawn chair.

10. Relax and enjoy the night sky.

Early Geminid meteor caught on the night of December 6, 2015, by Barry Simmons in Lake Martin, Alabama.

1. Be sure you know which days the shower will peak. Meteor showers happen over many days, as Earth encounters a wide stream of icy particles in space: debris left behind by a comet. The peak is just what it implies. It’s a point in time when Earth is expected to encounter the greatest number of particles from a particular meteor stream. You can find peak dates nowadays easily on the Internet. Try EarthSky’s meteor guide for 2016. Be aware that most, but not all, meteor showers are best after midnight.

And here’s the catch …

The peak of the shower comes at the same time for all of us on Earth. Meanwhile, our clocks are saying different times. So …

2. Find out the time of the shower’s peak in your timezone. You don’t need to watch exactly at the peak time. But it can help you decide which night is absolutely best for you.

Different sources might list different times for the peak of a meteor shower. In that case, go with a source you trust. Here at EarthSky, we trust the Observer’s Handbook from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Predictions are not always spot on, and the peak typically stretches over a day or so.

See how it works?

The time of the peak will nearly always be given in UTC. That stands for Coordinated Universal Time, and it’s the primary time standard by which the world regulates clocks and time. Learn to translate UTC to your time zone in this article.

3. Watch on the nights around the peak, too. If you miss a shower’s peak, you might not see as many meteors. But don’t let that discourage you! As we’ve mentioned before, predictions for meteor shower peaks are not always right on the money. It’s possible to see very nice meteor displays hours before or after the published peak.

For example, who can forget the famous 1998 Leonid meteor shower? The predicted peak favored observers in Europe, and yet those of us in the states were nevertheless treated to wonderful displays of Leonids on the nights before and after the predicted peak.

Just remember, meteor showers are part of nature. They often defy prediction.

The Geminid meteors radiate from near the star Castor in Gemini.

4. Understanding the shower’s radiant point can help. A meteor shower’s radiant point is that point in the sky from which the meteors will appear to radiate. Some people seem to think they have to be able to identify the radiant point in order to be able to watch the shower, but that is a serious misconception.

You can see meteors shoot up from the horizon before a shower’s radiant has even risen into the sky.

Here’s the power of the radiant point. Once it has risen into your sky, you’ll see more meteors. When it’s at its highest overhead – assuming you’re watching at a time when the shower has been producing meteors steadily over many hours – you’ll see the most meteors.

So find out the radiant point’s rising time. It can help you pinpoint the best time of night to watch the shower.

Randy Baumhover captured this image at Meyers Creek Beach on the Oregon coast.

5. Find out the shower’s expected rate, or number of meteors per hour. Here we touch on a topic that often leads to some bad feelings, especially among novice meteor watchers. Tables of meteor showers almost always list what is known as the zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) for each shower.

The ZHR is the number of meteors you’ll see if you’re watching in a very dark sky, when the radiant overhead, when the shower is at its peak.

In other words, the ZHR represents the number of meteors you might see per hour given the very best observing conditions during the shower’s maximum.

Now let’s apply this term to a real world example. Let’s say the December Geminid meteor shower has a ZHR of 120 meteors per hour. That doesn’t mean you’ll see 120 meteors per hour, but it does mean you might if you’re watching on a peak night in a dark sky, when the radiant is highest.

If the peak occurs when it’s still daylight at your location, if most of the meteors are predominantly faint, if a bright moon is out , or if you’re located in a light-polluted area, the total number of meteors you see will be considerably reduced.

Also know that most meteor showers have bursts of activity, with lulls in between. That’s why you should plan to watch the shower, from a dark location, for at least an hour or more. Several hours per night for several nights will give you the best chance of seeing the best show.

And that brings us to one of the most important factors of all for meteor-watchers…

6. You must be aware of the phase of the moon. If the moon is at a quarter phase or greater, you’re going to miss meteors, even if your skies are otherwise dark. It’s okay if the moon sets before the radiant rises, because the Earth blocks the moon’s light from the sky. But nothing dampens the display of a meteor shower more effectively than the presence of a bright moon.

Now you’re almost ready. Just a few final tips.

7. Dress warmly. The nights can be cool or cold, even during the spring and summer months.

8. Bring along that thermos of hot coffee or tea. It’ll be your friend at 3 a.m.

9. Bring a blanket or lawn chair for reclining comfortably while looking up at the sky. If you’re observing with a friend, set your chairs out back to back, and look at different parts of the sky. Then when one of you sees a meteors, he or she can call out “meteor,” and everyone can turn and look.

10. Relax and enjoy the night sky. Not every meteor shower is a winner. Sometimes, you may come away from a shower seeing only one meteor. But consider this. If that one meteor is a bright one that takes a slow path across a starry night sky … it’ll be worth it.

To be really successful at observing any meteor shower, you need to get into a kind of Zen state, waiting and expecting the meteors to come to you if you place yourself in the position to see them. Or forget the Zen state, and let yourself be guided by this old meteor watcher’s motto:

You might see a lot or you might not see many, but if you stay in the house, you won’t see any.

By the way, if you’re interested in learning more about meteor showers, or want to contribute meteor counts and brightness estimations, contact the following organizations: The American Meteor Society and the International Meteor Organization. Both provided the latest predictions as well as information to guide you in serious meteor observing.

View larger. | Early Geminid fireball caught on December 2, 2015 at 10:34 p.m. from the Tucson, Arizona foothills. Photo via Eliot Herman.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: How to watch a meteor shower. Tips for beginners.

EarthSky’s meteor guide for 2016

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/1lsGYLX