View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Dr Ski in Valencia, Philippines, caught the last quarter moon shortly after it rose around midnight on the morning of September 22, 2019. This moon phase is perfect for helping you envision the location of the sun … below your feet. Thanks, Dr Ski!

A last quarter moon appears half-lit by sunshine and half-immersed in its own shadow. It rises in the middle of the night, appears at its highest in the sky around dawn, and sets around midday.

On a last quarter moon, the lunar terminator – the shadow line dividing day and night – shows you where it’s sunset on the moon.

A last quarter moon provides a great opportunity to think of yourself on a three-dimensional world in space. For example, it’s fun to see this moon just after moonrise, shortly after midnight. Then the lighted portion points downward, to the sun below your feet. Think of the last quarter moon as a mirror to the world you’re standing on. Think of yourself standing in the middle of Earth’s nightside, on the midnight portion of Earth.

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

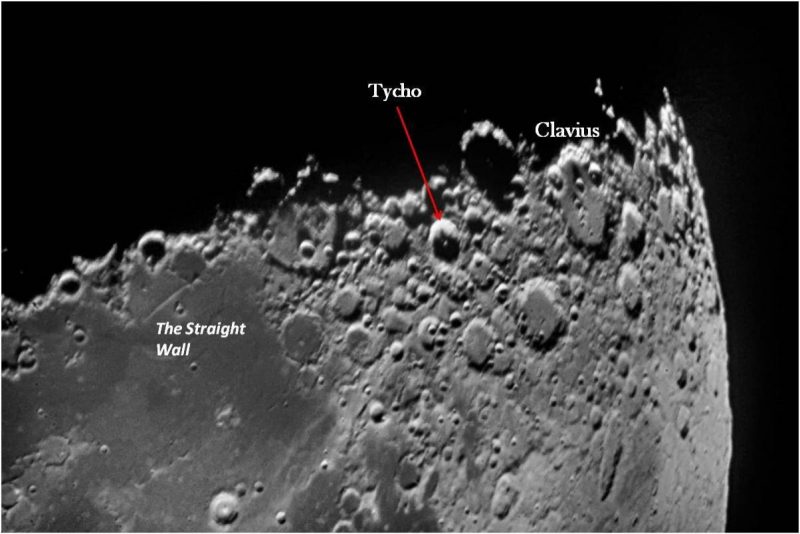

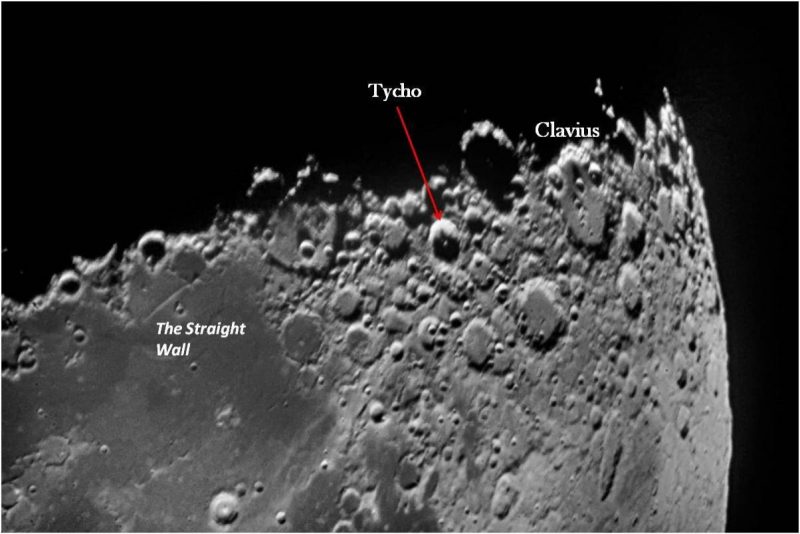

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | September 22, 2019, photo by Dr Ski. He wrote: “The moon’s southern limb at last quarter. The Straight Wall is either black or white depending on the angle of the sun’s rays. At lunar sunset (now), it’s white. Around full moon, Tycho is one of the easiest craters to find due to the impact rays emanating from it. It’s like the hub of a spoked wheel! At last quarter, Tycho becomes unremarkable. Clavius, on the other hand, becomes remarkable at high magnification.”

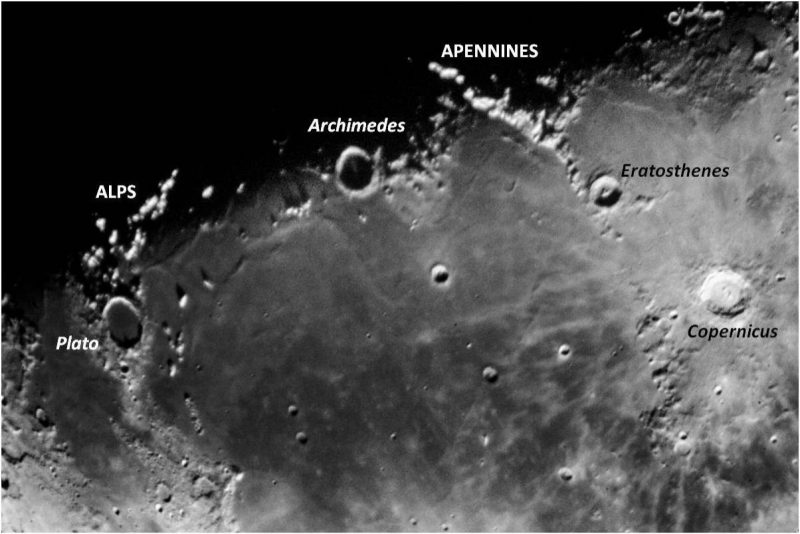

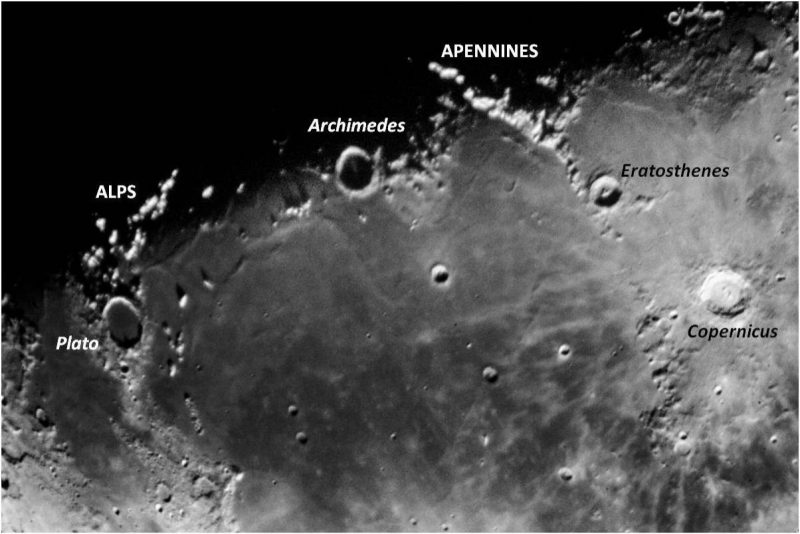

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | September 22, 2019, photo by Dr Ski. He wrote: “The Sea of Rains at last quarter. The lunar Alps and Apennines are bisected by the moon’s meridian. You can get an idea of the height of these mountains by how far they extend into the dark side of the terminator. At an elevation of over 5,000 meters [16,000 feet], the Apennines are twice as tall as the Alps.”

Also, a last quarter moon can be used as a guidepost to Earth’s direction of motion in orbit around the sun.

In other words, when you look toward a last quarter moon high in the predawn sky, for example, you’re gazing out approximately along the path of Earth’s orbit, in a forward direction. The moon is moving in orbit around the sun with the Earth and never holds still. But, if we could somehow anchor the moon in space … tie it down, keep it still … Earth’s orbital speed of 18 miles per second would carry us across the space between us and the moon in only a few hours.

Want to read more about the last quarter moon as a guidepost for Earth’s motion? Astronomer Guy Ottewell talks about it here.

A great thing about using the moon as a guidepost to Earth’s motion is that you can do it anywhere … as, for example, in the photo below, from large cities.

Ben Orlove wrote from New York City: “I was sitting in the roof garden of my building, and there was the moon, right in front of me. You were right, this is a perfect time to visualize … the Earth’s motion.”

As the moon orbits Earth, it changes phase in an orderly way. Read more: 4 keys to understanding moon phases

Bottom line: The moon reaches its last quarter phase on November 19, 2019, at 21:11 UTC. In the coming week, watch for it to rise in the east in the hours after midnight, waning thinner each morning. Translate UTC to your time.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ze0n1D

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Dr Ski in Valencia, Philippines, caught the last quarter moon shortly after it rose around midnight on the morning of September 22, 2019. This moon phase is perfect for helping you envision the location of the sun … below your feet. Thanks, Dr Ski!

A last quarter moon appears half-lit by sunshine and half-immersed in its own shadow. It rises in the middle of the night, appears at its highest in the sky around dawn, and sets around midday.

On a last quarter moon, the lunar terminator – the shadow line dividing day and night – shows you where it’s sunset on the moon.

A last quarter moon provides a great opportunity to think of yourself on a three-dimensional world in space. For example, it’s fun to see this moon just after moonrise, shortly after midnight. Then the lighted portion points downward, to the sun below your feet. Think of the last quarter moon as a mirror to the world you’re standing on. Think of yourself standing in the middle of Earth’s nightside, on the midnight portion of Earth.

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | September 22, 2019, photo by Dr Ski. He wrote: “The moon’s southern limb at last quarter. The Straight Wall is either black or white depending on the angle of the sun’s rays. At lunar sunset (now), it’s white. Around full moon, Tycho is one of the easiest craters to find due to the impact rays emanating from it. It’s like the hub of a spoked wheel! At last quarter, Tycho becomes unremarkable. Clavius, on the other hand, becomes remarkable at high magnification.”

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | September 22, 2019, photo by Dr Ski. He wrote: “The Sea of Rains at last quarter. The lunar Alps and Apennines are bisected by the moon’s meridian. You can get an idea of the height of these mountains by how far they extend into the dark side of the terminator. At an elevation of over 5,000 meters [16,000 feet], the Apennines are twice as tall as the Alps.”

Also, a last quarter moon can be used as a guidepost to Earth’s direction of motion in orbit around the sun.

In other words, when you look toward a last quarter moon high in the predawn sky, for example, you’re gazing out approximately along the path of Earth’s orbit, in a forward direction. The moon is moving in orbit around the sun with the Earth and never holds still. But, if we could somehow anchor the moon in space … tie it down, keep it still … Earth’s orbital speed of 18 miles per second would carry us across the space between us and the moon in only a few hours.

Want to read more about the last quarter moon as a guidepost for Earth’s motion? Astronomer Guy Ottewell talks about it here.

A great thing about using the moon as a guidepost to Earth’s motion is that you can do it anywhere … as, for example, in the photo below, from large cities.

Ben Orlove wrote from New York City: “I was sitting in the roof garden of my building, and there was the moon, right in front of me. You were right, this is a perfect time to visualize … the Earth’s motion.”

As the moon orbits Earth, it changes phase in an orderly way. Read more: 4 keys to understanding moon phases

Bottom line: The moon reaches its last quarter phase on November 19, 2019, at 21:11 UTC. In the coming week, watch for it to rise in the east in the hours after midnight, waning thinner each morning. Translate UTC to your time.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ze0n1D