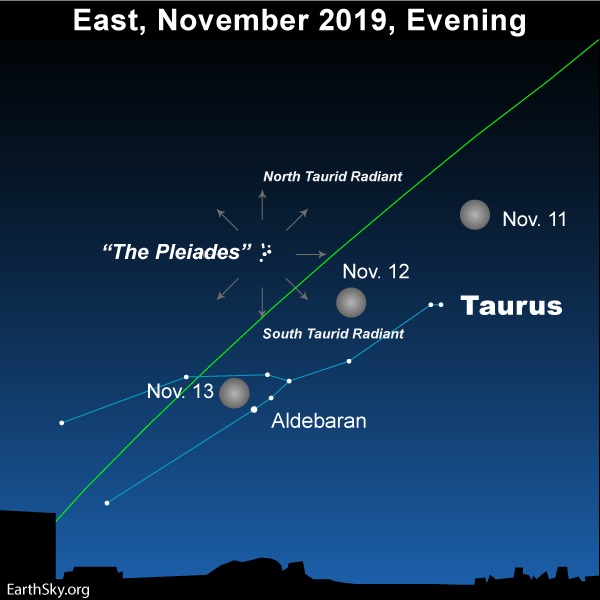

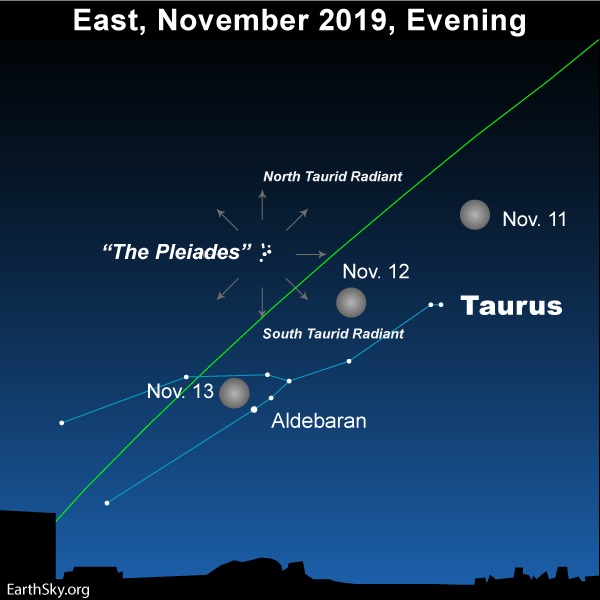

The full moon is sweeping through Taurus around November 11-13, 2019. On the same evenings, the North Taurid meteor shower – which radiates from this constellation – is reaching its peak.

Full moon comes on November 12, 2019, as the moon is sweeping through the constellation Taurus the Bull. As viewed from all parts of Earth, the full moon will light up the nighttime from dusk until dawn. This bright moon comes at the wrong time for meteor-watching enthusiasts, because – on the evening of November 11, into the morning of November 12 – the long-lasting North Taurid meteor shower also reaches a peak.

Read more: Want more about the meteor shower? Try this article: North Taurid meteors in moonlight

In North America, we often call the November full moon the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon. In the Southern Hemisphere, where’s it’s now the springtime season, this November full moon is more associated with springtime flowers than with late autumn frosts.

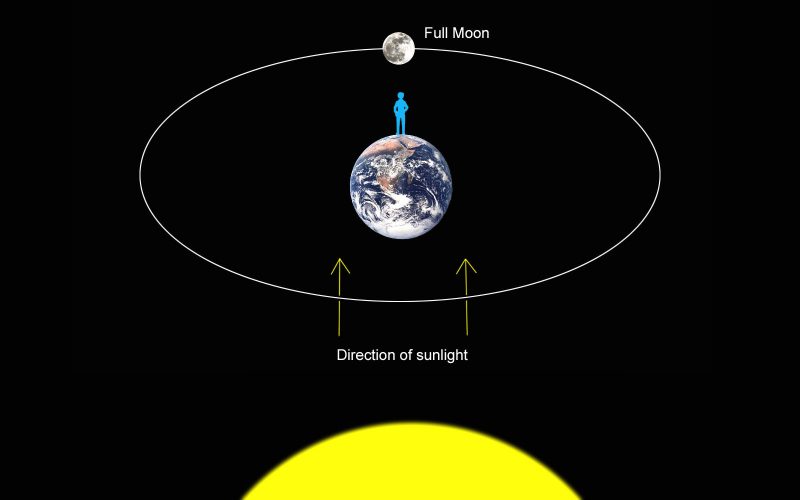

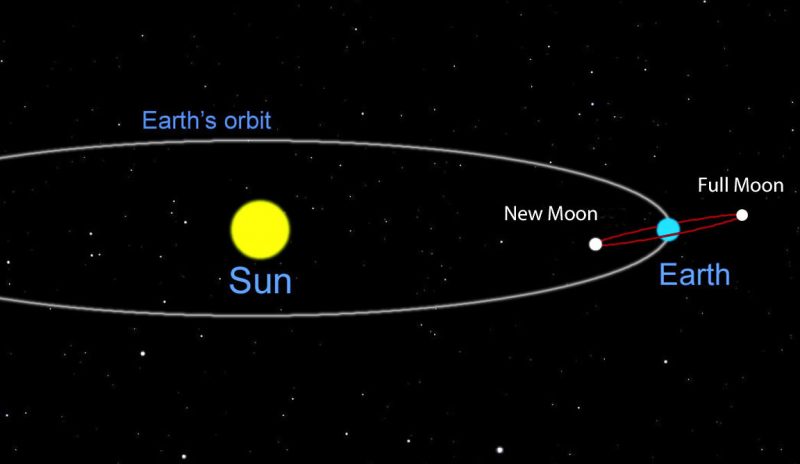

Although the moon might look full to the eye for two to three nights in a row, astronomers say the moon is truly full at a well-defined instant. Full moon occurs when the moon is precisely 180 degrees opposite the sun in ecliptic longitude. In other words, the elongation between the moon and sun is 180 degrees at full moon.

Visit unitarium.com to find out the present moon-sun elongation, remembering that a positive number refers to a waxing moon, whereas a negative number indicates a waning moon.

The full moon arrives on November 12, 2019, at 13:34 Universal Time (UTC). Although the instant of full moon happens at the same time worldwide, the clock differs by time zone. For us in the United States, the full moon occurs on November 12, at 8:34 a.m. Eastern Time, 7:34 a.m. Central Time, 6:34 a.m. Mountain Time, 5:34 a.m. Pacific Time, 4:34 a.m. Alaskan Time and 3:34 a.m. Hawaiian Time.

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

The day and night sides of Earth at full moon (November 12, 2019, at 13:34 Universal Time). The shadow line at left (running through North America) depicts sunrise (moonset) November 12, whereas the shadow line at right (crossing eastern Europe and the Middle East) represents sunset (moonrise) November 12. Image via EarthView.

Bottom line: Full moon comes on November 12, 2019, as the moon is sweeping through the constellation Taurus the Bull. This full moon comes on the peak night of the North Taurid meteor shower.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/32y6WsA

The full moon is sweeping through Taurus around November 11-13, 2019. On the same evenings, the North Taurid meteor shower – which radiates from this constellation – is reaching its peak.

Full moon comes on November 12, 2019, as the moon is sweeping through the constellation Taurus the Bull. As viewed from all parts of Earth, the full moon will light up the nighttime from dusk until dawn. This bright moon comes at the wrong time for meteor-watching enthusiasts, because – on the evening of November 11, into the morning of November 12 – the long-lasting North Taurid meteor shower also reaches a peak.

Read more: Want more about the meteor shower? Try this article: North Taurid meteors in moonlight

In North America, we often call the November full moon the Beaver Moon or Frost Moon. In the Southern Hemisphere, where’s it’s now the springtime season, this November full moon is more associated with springtime flowers than with late autumn frosts.

Although the moon might look full to the eye for two to three nights in a row, astronomers say the moon is truly full at a well-defined instant. Full moon occurs when the moon is precisely 180 degrees opposite the sun in ecliptic longitude. In other words, the elongation between the moon and sun is 180 degrees at full moon.

Visit unitarium.com to find out the present moon-sun elongation, remembering that a positive number refers to a waxing moon, whereas a negative number indicates a waning moon.

The full moon arrives on November 12, 2019, at 13:34 Universal Time (UTC). Although the instant of full moon happens at the same time worldwide, the clock differs by time zone. For us in the United States, the full moon occurs on November 12, at 8:34 a.m. Eastern Time, 7:34 a.m. Central Time, 6:34 a.m. Mountain Time, 5:34 a.m. Pacific Time, 4:34 a.m. Alaskan Time and 3:34 a.m. Hawaiian Time.

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

The day and night sides of Earth at full moon (November 12, 2019, at 13:34 Universal Time). The shadow line at left (running through North America) depicts sunrise (moonset) November 12, whereas the shadow line at right (crossing eastern Europe and the Middle East) represents sunset (moonrise) November 12. Image via EarthView.

Bottom line: Full moon comes on November 12, 2019, as the moon is sweeping through the constellation Taurus the Bull. This full moon comes on the peak night of the North Taurid meteor shower.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/32y6WsA