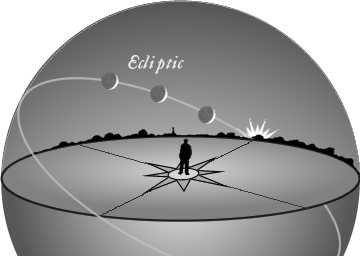

Have you seen any meteors streaking across the sky this month? If they are coming from the northern sky, they might have been Draconids, whose peak has passed. If they’re coming from along the ecliptic, or sun’s path across our sky, they might be part of the long-lasting South Taurid meteor shower, which is still going on. But some meteors you’ve seen could also be part of the annual Orionid meteor shower, which is now building to its peak on the morning of October 21 or 22.

Orionid meteors fly each year between about October 2 to November 7. That’s when Earth is passing through the stream of debris left behind by Comet Halley, the parent comet of the Orionid shower. In 2019, on the peak mornings, the moon will be at or shortly past its last quarter phase, somewhat interfering with the show. The Orionids usually put out the greatest number of meteors in the few hours before dawn.

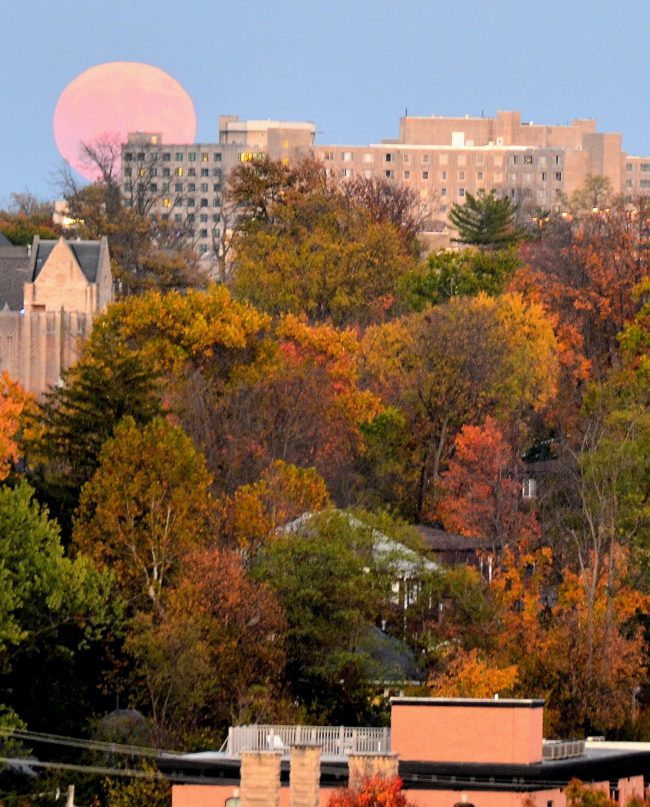

John Ashley captured this photo from Montana during the 2015 Orionid shower.

The term meteor shower might give you the idea of a rain shower. But few meteor showers resemble showers of rain. The Orionids aren’t the year’s strongest shower, and they’re not particularly known for storming (producing unexpected, very rich displays). From a dark location, in a year when the moon is out of the way, you might reliably see 10 to 20 Orionids per hour at their peak. Will you see that many in 2019? Well … maybe. There’s always the element of uncertainly and possible surprise when it comes to meteor showers.

If you do see any Orionids in 2019, note that they’re known to be extremely fast meteors, plummeting into the Earth’s atmosphere at about 66 kilometers – 41 miles – per second. The meteors in this shower are on the faint side. But they make up for that; maybe half of the Orionid meteors leave persistent trains, or ionized gas trails that last for a few seconds after the meteor itself has gone.

Also, sometimes, an Orionid meteor can be exceptionally bright and break up into fragments.

Again, the peak morning is likely October 22. Do start watching in the days ahead of the peak, though. You might catch an Orionid meteor or two before dawn over the coming days.

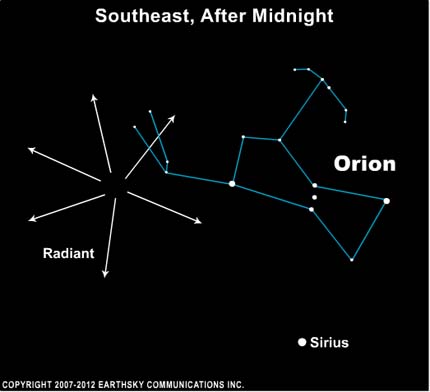

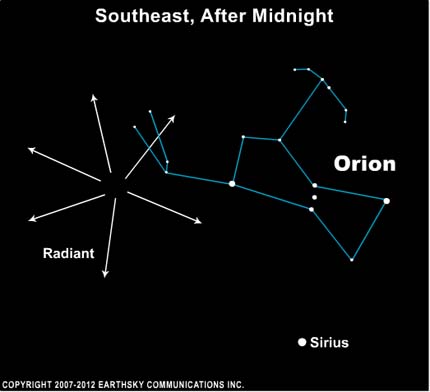

How will you know it’s an Orionid? You’ll know because it’ll come from the shower’s radiant point. See the chart below.

The Orionids radiate from a point near the upraised Club of the constellation Orion the Hunter. The bright star near the radiant point is Betelgeuse.

Orionid meteors radiate from constellation Orion. Meteors in annual showers are named for the point in our sky from which they appear to radiate. The radiant point for the Orionids is in the direction of the famous constellation Orion the Hunter, which you’ll find ascending in the east in the hours after midnight. Hence the name Orionids.

You don’t need to know Orion, or be staring toward it, to see the meteors. The meteors often don’t become visible until they are 30 degrees or so from their radiant point. And, remember, they are streaking out from the radiant in all directions. They will appear in all parts of the sky.

However, if you do see a meteor – and trace its path backward – you might see that it comes from the Club of Orion. And, if so, that meteor will be an Orionid. You might know Orion’s bright, ruddy star Betelgeuse. The radiant is north of Betelgeuse.

So … in which direction do you look? No particular direction. It’s best to find a wide-open viewing area. Sometimes friends like to watch together, facing different directions. When somebody sees one, that person can call out meteor!

Brian Brace caught the 2014 Orionid shower and wrote, “A few hours into our adventure, we’d witnessed only a few meteors flying by. But right before I took the camera down this huge fireball streamed across the northeastern sky. That one meteor made the whole night worth it.”

Orionid meteors stem from Comet Halley. Meteors are fancifully called shooting stars. Of course, they aren’t really stars. They’re debris left behind by comets, burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The Orionid meteors are debris left behind by Comet Halley, arguably the most famous of all comets, which last visited Earth in 1986. This comet leaves debris in its wake that strikes Earth’s atmosphere most fully around October 20-22, while Earth intersects the comet’s orbit, as it does every year at this time.

Particles shed by the comet slam into our upper atmosphere, where they vaporize at some 60 miles (100 km) above Earth’s surface.

Even one meteor can be a thrill. But you might want to observe for an hour or more, and in that case the trick is to find a place to observe in the country. Bring along a blanket or lawn chair and lie back comfortably while gazing upward.

Halley’s Comet, perhaps the most famous of all comets, is parent of both the Eta Aquarid meteor shower in May and October’s Orionid meteor shower. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: In 2019, the Orionid meteor shower is expected to rain down its greatest number of meteors on the morning of October 21 or 22. On that night, a waxing gibbous moon will set only an hour or two before morning twilight begins. Try watching in the days before the peak when there will be less moonlight in the sky. Or plan to watch in the hours before dawn on October 21.

EarthSky’s meteor shower guide for 2018

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Vzf2Py

Have you seen any meteors streaking across the sky this month? If they are coming from the northern sky, they might have been Draconids, whose peak has passed. If they’re coming from along the ecliptic, or sun’s path across our sky, they might be part of the long-lasting South Taurid meteor shower, which is still going on. But some meteors you’ve seen could also be part of the annual Orionid meteor shower, which is now building to its peak on the morning of October 21 or 22.

Orionid meteors fly each year between about October 2 to November 7. That’s when Earth is passing through the stream of debris left behind by Comet Halley, the parent comet of the Orionid shower. In 2019, on the peak mornings, the moon will be at or shortly past its last quarter phase, somewhat interfering with the show. The Orionids usually put out the greatest number of meteors in the few hours before dawn.

John Ashley captured this photo from Montana during the 2015 Orionid shower.

The term meteor shower might give you the idea of a rain shower. But few meteor showers resemble showers of rain. The Orionids aren’t the year’s strongest shower, and they’re not particularly known for storming (producing unexpected, very rich displays). From a dark location, in a year when the moon is out of the way, you might reliably see 10 to 20 Orionids per hour at their peak. Will you see that many in 2019? Well … maybe. There’s always the element of uncertainly and possible surprise when it comes to meteor showers.

If you do see any Orionids in 2019, note that they’re known to be extremely fast meteors, plummeting into the Earth’s atmosphere at about 66 kilometers – 41 miles – per second. The meteors in this shower are on the faint side. But they make up for that; maybe half of the Orionid meteors leave persistent trains, or ionized gas trails that last for a few seconds after the meteor itself has gone.

Also, sometimes, an Orionid meteor can be exceptionally bright and break up into fragments.

Again, the peak morning is likely October 22. Do start watching in the days ahead of the peak, though. You might catch an Orionid meteor or two before dawn over the coming days.

How will you know it’s an Orionid? You’ll know because it’ll come from the shower’s radiant point. See the chart below.

The Orionids radiate from a point near the upraised Club of the constellation Orion the Hunter. The bright star near the radiant point is Betelgeuse.

Orionid meteors radiate from constellation Orion. Meteors in annual showers are named for the point in our sky from which they appear to radiate. The radiant point for the Orionids is in the direction of the famous constellation Orion the Hunter, which you’ll find ascending in the east in the hours after midnight. Hence the name Orionids.

You don’t need to know Orion, or be staring toward it, to see the meteors. The meteors often don’t become visible until they are 30 degrees or so from their radiant point. And, remember, they are streaking out from the radiant in all directions. They will appear in all parts of the sky.

However, if you do see a meteor – and trace its path backward – you might see that it comes from the Club of Orion. And, if so, that meteor will be an Orionid. You might know Orion’s bright, ruddy star Betelgeuse. The radiant is north of Betelgeuse.

So … in which direction do you look? No particular direction. It’s best to find a wide-open viewing area. Sometimes friends like to watch together, facing different directions. When somebody sees one, that person can call out meteor!

Brian Brace caught the 2014 Orionid shower and wrote, “A few hours into our adventure, we’d witnessed only a few meteors flying by. But right before I took the camera down this huge fireball streamed across the northeastern sky. That one meteor made the whole night worth it.”

Orionid meteors stem from Comet Halley. Meteors are fancifully called shooting stars. Of course, they aren’t really stars. They’re debris left behind by comets, burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The Orionid meteors are debris left behind by Comet Halley, arguably the most famous of all comets, which last visited Earth in 1986. This comet leaves debris in its wake that strikes Earth’s atmosphere most fully around October 20-22, while Earth intersects the comet’s orbit, as it does every year at this time.

Particles shed by the comet slam into our upper atmosphere, where they vaporize at some 60 miles (100 km) above Earth’s surface.

Even one meteor can be a thrill. But you might want to observe for an hour or more, and in that case the trick is to find a place to observe in the country. Bring along a blanket or lawn chair and lie back comfortably while gazing upward.

Halley’s Comet, perhaps the most famous of all comets, is parent of both the Eta Aquarid meteor shower in May and October’s Orionid meteor shower. Image via NASA.

Bottom line: In 2019, the Orionid meteor shower is expected to rain down its greatest number of meteors on the morning of October 21 or 22. On that night, a waxing gibbous moon will set only an hour or two before morning twilight begins. Try watching in the days before the peak when there will be less moonlight in the sky. Or plan to watch in the hours before dawn on October 21.

EarthSky’s meteor shower guide for 2018

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Vzf2Py