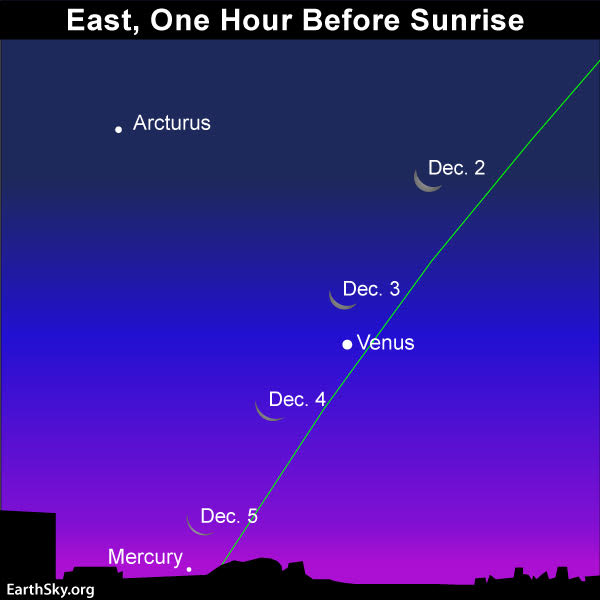

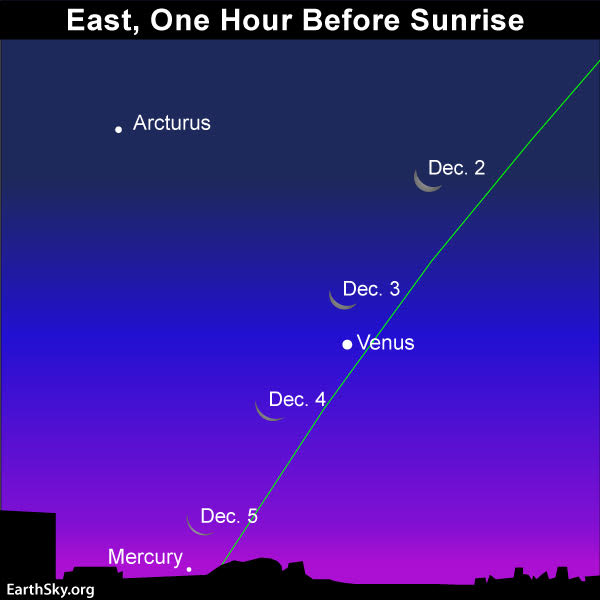

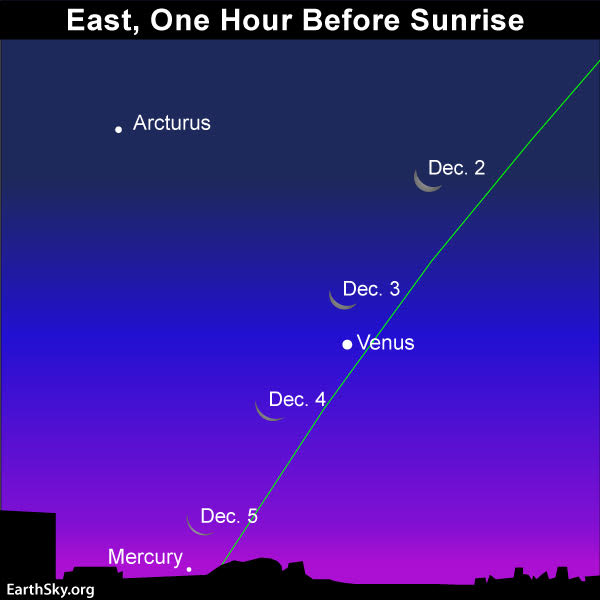

It’ll be tough to catch the slender crescent moon with the planet Mercury before sunrise December 5. But some of EarthSky’s eagle-eyed observers have surprised us before and may surprise us again! Read more.

Click the name of a planet to learn more about its visibility in December 2018: Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Mars and Mercury

The 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

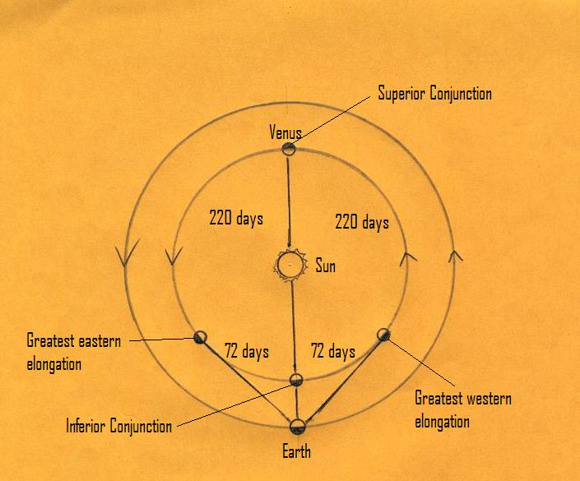

Venus is the brightest planet, beaming mightily the east before sunrise. As December 2018 begins, Venus is shining at greatest brilliancy, its brightest for this morning apparition. Although Venus will remain a fixture of the morning sky until mid-August 2019, it’ll grow dimmer, by a bit, after early December. Even so, as always, Venus will rank as the 3rd-brightest celestial body, after the sun and moon!

The waning crescent moon will join Venus in the morning sky for several days, centered on or near December 3. If you’re up before dawn, you can also see the stars Arcturus and Spica accompanying the moon and the queen planet, as depicted on the sky chart above.

At mid-northern latitudes, Venus rises about 3 1/2 hours before sunrise throughout December.

At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Venus rises about two hours before sunup in early December. By the month’s end, that’ll increase to about 3 hours.

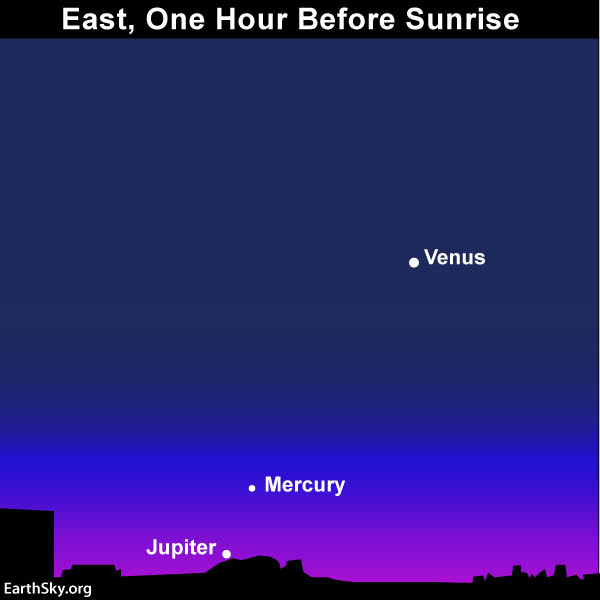

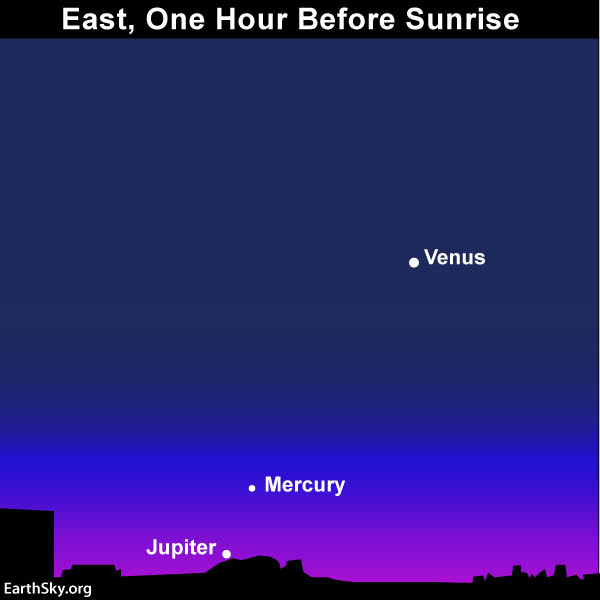

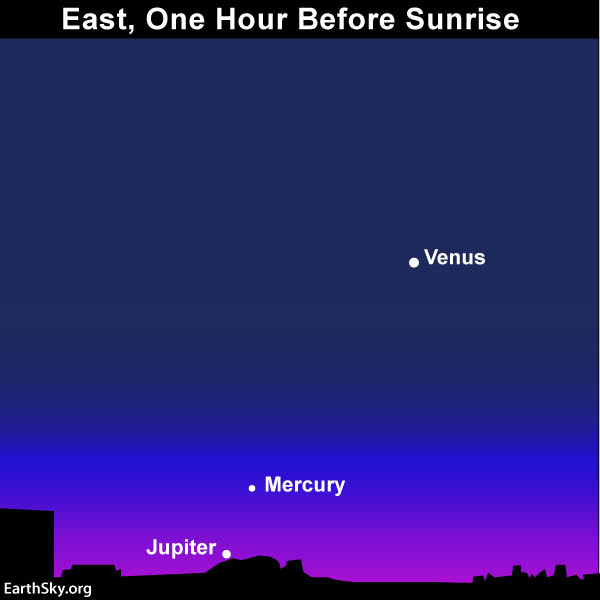

In mid-December 2018, look extra hard with the unaided eye or binoculars, and you just might spot the planet Jupiter near the horizon, and on line with Venus and Mercury. Read more.

Jupiter is the 2nd-brightest planet, after Venus. This planet exited the evening sky, and entered the morning sky, in late November. In the first week or two of December, Jupiter rises only a little while before the sun. It’ll be hard to see in the glare of morning twilight.

Jupiter will become easier to see before sunrise around mid-December, when it rises an hour or so before the sun. Around this time, Mercury reaches its greatest western (morning) elongation of 21 degrees from the rising sun. Because Mercury will rise before Jupiter does in mid-December, an imaginary line from Venus through Mercury may enable you to locate Jupiter near the horizon. See the above sky chart.

After mid-December, Jupiter will climb upward toward Mercury, as Mercury is sinking downward, toward Jupiter. Circle December 21 on your calendar, and watch for these two worlds to meet up for a close-knit conjunction. See the sky chart below.

Mercury and Jupiter are in conjunction on December 21, 2018. Very conveniently, these two worlds will easily fit within a single binocular field of view. Read more.

Jupiter rapidly climbs out of the glare of sunrise, coming up a solid two hours before the sun by the month’s end from most places worldwide. Mercury, though sinking sunward, will still rise a good hour before the sun on the last day of 2018. So, as the year draws to a close, watch for picturesque line-up of the waning crescent moon with Venus, Jupiter and Mercury about an hour before sunrise on December 31, as shown on the sky chart below.

On the last morning of the year – December 31, 2018 – watch for the moon to line up with the planets Venus, Jupiter and Mercury. Read more.

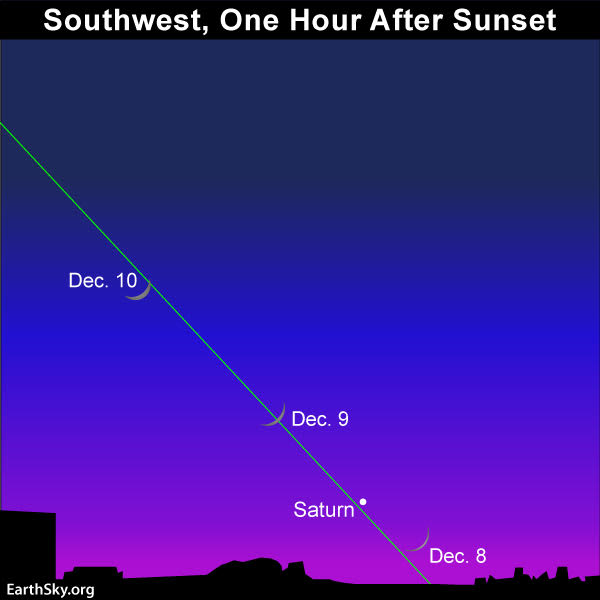

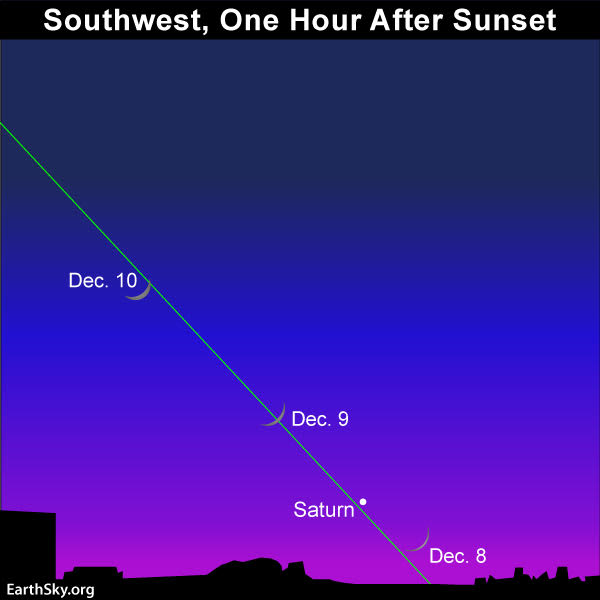

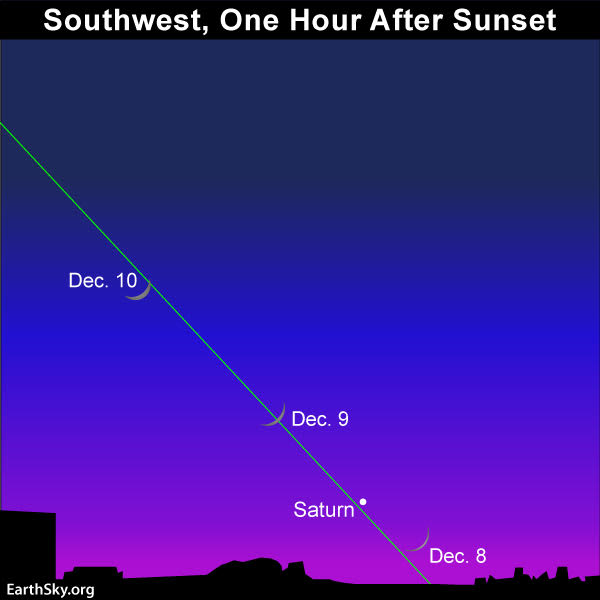

Mars and Saturn are the only two bright planets to appear the December 2018 evening sky – though Saturn, for the most part, only nominally so. Saturn sinks closer and closer to the sunset throughout December, and by mid-December will set too soon after the sun to be visible. Your best chance of spotting Saturn may be at dusk/nightfall on December 8 and 9, when the young waxing crescent moon swings rather close to Saturn on the sky’s dome. See the sky chart below.

Let the waxing crescent moon help guide your eye to the planet Saturn in December 2018. Saturn will disappear from the evening sky soon thereafter. Read more.

Fortunately, Mars remains bright and beautiful, shining more brilliantly than a 1st-magnitude star throughout December 2018. In December, Mars transits – reaches its highest point in the sky – at dusk in the Northern Hemisphere, yet before sunset in the Southern Hemisphere. Best of all, Mars stays out till around midnight in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Click here for a recommended sky almanac providing you with the transit times for Mars.

Watch for the moon to be in the vicinity of Mars for several evenings, centered on or near December 14. Fortunately, the moon will set before the peak hours of the Geminid meteor shower, centered around 2 in the morning on December 13 and 14. See the sky chart below.

On the expected peak night of the Geminids, the moon will be close to Mars on the sky’s dome. Mars’ setting at late night preludes the Geminid’s most prolific display of streaking meteors. Read more.

Saturn will swing over to the morning sky in January 2019, leaving Mars as the only bright planet to adorn the January 2019 evening sky.

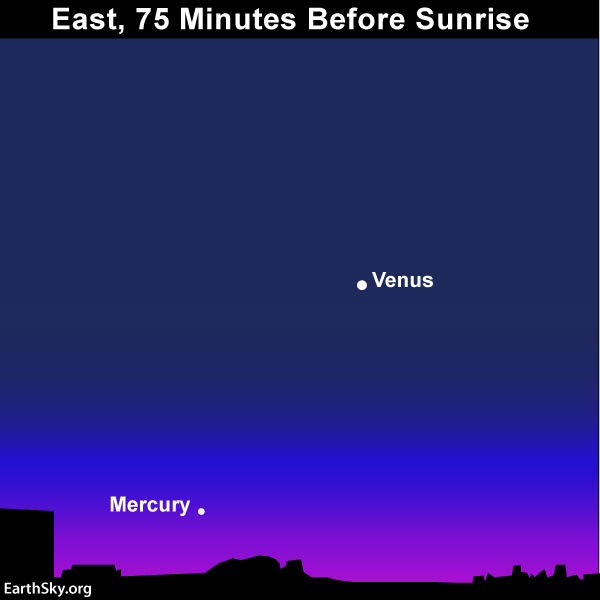

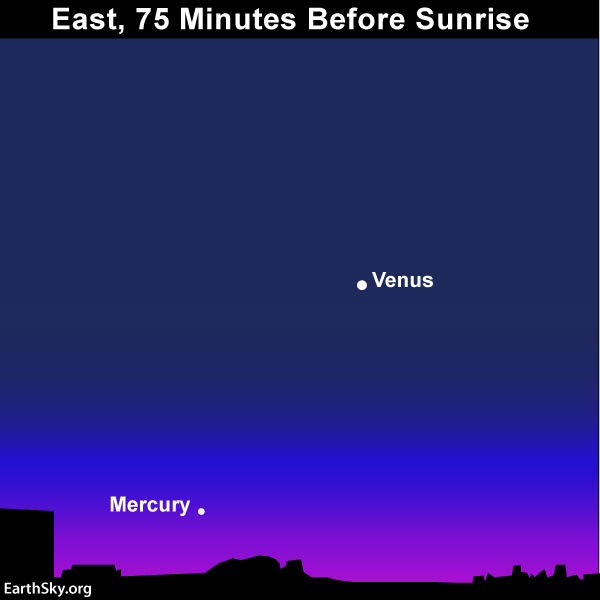

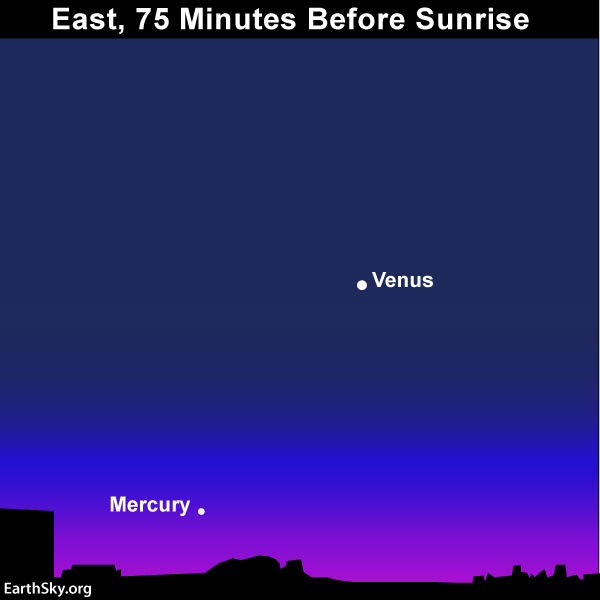

Mercury, the innermost planet of the solar system, is a morning planet all month long in December 2018. Mercury might become visible before sunrise by the end of the first week of December. Look for Mercury beneath Venus, as shown on the sky chart below. By mid-December, Mercury rises about 90 minutes before the sun at mid-northern latitudes; from temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, it’s more like 75 minutes before sunrise. The crowning moment will come on the solstice, when Mercury and Jupiter have their conjunction on December 21.

Let Venus help guide your eye to Mercury .Venus rises in the predawn hours whereas Mercury follows Venus into the morning sky as nighttime gives way to morning dawn. Read more.

What do we mean by bright planet? By bright planet, we mean any solar system planet that is easily visible without an optical aid and that has been watched by our ancestors since time immemorial. In their outward order from the sun, the five bright planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. These planets actually do appear bright in our sky. They are typically as bright as – or brighter than – the brightest stars. Plus, these relatively nearby worlds tend to shine with a steadier light than the distant, twinkling stars. You can spot them, and come to know them as faithful friends, if you try.

Skywatcher, by Predrag Agatonovic.

Bottom line: In December 2018, Mars shines in the evening sky all month long. Saturn disappears in the sunset glare by about mid-month. Venus lights up the eastern sky before sunrise all month. Mercury and Jupiter join Venus in the morning sky around mid-December. Click here for recommended almanacs; they can help you know when the planets rise, transit and set in your sky.

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to EarthSky News by email

Visit EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze, and recommend a place we can all enjoy. Zoom out for worldwide map.

Help EarthSky keep going! Donate now.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/1YD00CF

It’ll be tough to catch the slender crescent moon with the planet Mercury before sunrise December 5. But some of EarthSky’s eagle-eyed observers have surprised us before and may surprise us again! Read more.

Click the name of a planet to learn more about its visibility in December 2018: Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Mars and Mercury

The 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

Venus is the brightest planet, beaming mightily the east before sunrise. As December 2018 begins, Venus is shining at greatest brilliancy, its brightest for this morning apparition. Although Venus will remain a fixture of the morning sky until mid-August 2019, it’ll grow dimmer, by a bit, after early December. Even so, as always, Venus will rank as the 3rd-brightest celestial body, after the sun and moon!

The waning crescent moon will join Venus in the morning sky for several days, centered on or near December 3. If you’re up before dawn, you can also see the stars Arcturus and Spica accompanying the moon and the queen planet, as depicted on the sky chart above.

At mid-northern latitudes, Venus rises about 3 1/2 hours before sunrise throughout December.

At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Venus rises about two hours before sunup in early December. By the month’s end, that’ll increase to about 3 hours.

In mid-December 2018, look extra hard with the unaided eye or binoculars, and you just might spot the planet Jupiter near the horizon, and on line with Venus and Mercury. Read more.

Jupiter is the 2nd-brightest planet, after Venus. This planet exited the evening sky, and entered the morning sky, in late November. In the first week or two of December, Jupiter rises only a little while before the sun. It’ll be hard to see in the glare of morning twilight.

Jupiter will become easier to see before sunrise around mid-December, when it rises an hour or so before the sun. Around this time, Mercury reaches its greatest western (morning) elongation of 21 degrees from the rising sun. Because Mercury will rise before Jupiter does in mid-December, an imaginary line from Venus through Mercury may enable you to locate Jupiter near the horizon. See the above sky chart.

After mid-December, Jupiter will climb upward toward Mercury, as Mercury is sinking downward, toward Jupiter. Circle December 21 on your calendar, and watch for these two worlds to meet up for a close-knit conjunction. See the sky chart below.

Mercury and Jupiter are in conjunction on December 21, 2018. Very conveniently, these two worlds will easily fit within a single binocular field of view. Read more.

Jupiter rapidly climbs out of the glare of sunrise, coming up a solid two hours before the sun by the month’s end from most places worldwide. Mercury, though sinking sunward, will still rise a good hour before the sun on the last day of 2018. So, as the year draws to a close, watch for picturesque line-up of the waning crescent moon with Venus, Jupiter and Mercury about an hour before sunrise on December 31, as shown on the sky chart below.

On the last morning of the year – December 31, 2018 – watch for the moon to line up with the planets Venus, Jupiter and Mercury. Read more.

Mars and Saturn are the only two bright planets to appear the December 2018 evening sky – though Saturn, for the most part, only nominally so. Saturn sinks closer and closer to the sunset throughout December, and by mid-December will set too soon after the sun to be visible. Your best chance of spotting Saturn may be at dusk/nightfall on December 8 and 9, when the young waxing crescent moon swings rather close to Saturn on the sky’s dome. See the sky chart below.

Let the waxing crescent moon help guide your eye to the planet Saturn in December 2018. Saturn will disappear from the evening sky soon thereafter. Read more.

Fortunately, Mars remains bright and beautiful, shining more brilliantly than a 1st-magnitude star throughout December 2018. In December, Mars transits – reaches its highest point in the sky – at dusk in the Northern Hemisphere, yet before sunset in the Southern Hemisphere. Best of all, Mars stays out till around midnight in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Click here for a recommended sky almanac providing you with the transit times for Mars.

Watch for the moon to be in the vicinity of Mars for several evenings, centered on or near December 14. Fortunately, the moon will set before the peak hours of the Geminid meteor shower, centered around 2 in the morning on December 13 and 14. See the sky chart below.

On the expected peak night of the Geminids, the moon will be close to Mars on the sky’s dome. Mars’ setting at late night preludes the Geminid’s most prolific display of streaking meteors. Read more.

Saturn will swing over to the morning sky in January 2019, leaving Mars as the only bright planet to adorn the January 2019 evening sky.

Mercury, the innermost planet of the solar system, is a morning planet all month long in December 2018. Mercury might become visible before sunrise by the end of the first week of December. Look for Mercury beneath Venus, as shown on the sky chart below. By mid-December, Mercury rises about 90 minutes before the sun at mid-northern latitudes; from temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, it’s more like 75 minutes before sunrise. The crowning moment will come on the solstice, when Mercury and Jupiter have their conjunction on December 21.

Let Venus help guide your eye to Mercury .Venus rises in the predawn hours whereas Mercury follows Venus into the morning sky as nighttime gives way to morning dawn. Read more.

What do we mean by bright planet? By bright planet, we mean any solar system planet that is easily visible without an optical aid and that has been watched by our ancestors since time immemorial. In their outward order from the sun, the five bright planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. These planets actually do appear bright in our sky. They are typically as bright as – or brighter than – the brightest stars. Plus, these relatively nearby worlds tend to shine with a steadier light than the distant, twinkling stars. You can spot them, and come to know them as faithful friends, if you try.

Skywatcher, by Predrag Agatonovic.

Bottom line: In December 2018, Mars shines in the evening sky all month long. Saturn disappears in the sunset glare by about mid-month. Venus lights up the eastern sky before sunrise all month. Mercury and Jupiter join Venus in the morning sky around mid-December. Click here for recommended almanacs; they can help you know when the planets rise, transit and set in your sky.

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to EarthSky News by email

Visit EarthSky’s Best Places to Stargaze, and recommend a place we can all enjoy. Zoom out for worldwide map.

Help EarthSky keep going! Donate now.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/1YD00CF