Preliminary summary of the tracks of all tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Basin during the 2018 hurricane season. Image via TheHurricaneEditorMaker/Wikimedia.

Hurricane season in the Atlantic basin, an area that includes the North Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico, ends on November 30th. Hurricanes during November are rare events, but they do occur and they can be deadly. In general, one November hurricane can be expected in the Atlantic basin every three or so years.

Hurricanes during November are rare because of the onset of cooler ocean temperatures and changes in wind shear in the Northern Hemisphere. These conditions are less favorable for the development of hurricanes. The hurricane season for the Atlantic basin runs from June 1 to November 30, which is the timeframe during which most hurricanes develop.

According to data compiled by NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory for the years 1851–2015, there have been 58 November hurricanes in total and only five that made landfall in the U.S. Now compare those numbers to the data for the month of September, which is the peak of hurricane season. During the same 164 year period, there were 395 September hurricanes and 107 that made landfall. That is a 6.8-fold decrease in the number of hurricanes that developed during those months, and a 21.4-fold decrease in the number that made landfall.

The Weather Channel, by using data collected since 1950, has estimated that a November hurricane will occur roughly once every three years. That article does a great job of summarizing some famous November hurricanes including Hurricane Kate and Hurricane Otto. Hurricane Kate made landfall just before Thanksgiving on November 21, 1985, near Mexico Beach, Florida. This represents the latest that a hurricane has made landfall according to modern recordkeeping. In long-term records dating back to 1851, the record for the latest landfall goes to Hurricane Otto, which came onshore at Nicaragua on Thanksgiving, November 24, 2016.

Together, the above data illustrate that November hurricanes are indeed a rare occurrence. However, these storms can be deadly and damaging.

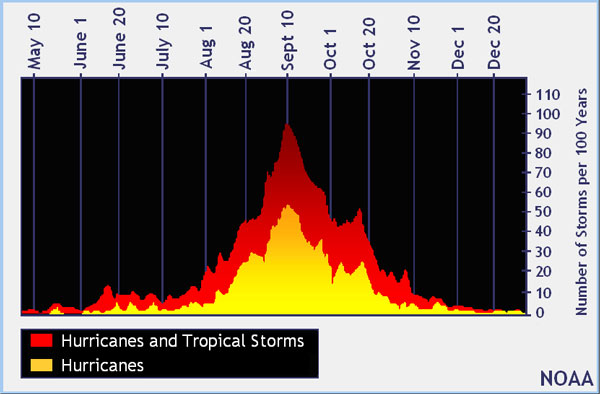

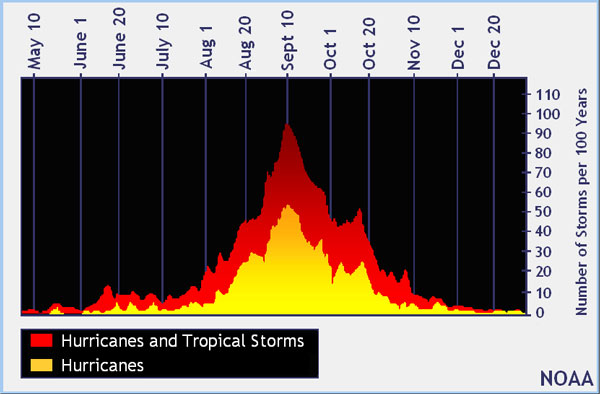

Monthly frequency of tropical storms and hurricanes. Image via U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

To date, there have been 15 named storms including eight hurricanes and two major hurricanes (greater than a category 3) during the 2018 hurricane season. Quiet conditions are expected for the next several days, but don’t let your guard down just yet.

EarthSky’s 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

Bottom line: November hurricanes are rare events, but they do occur and they can be deadly. The record for the latest U.S. landfall is held by Hurricane Otto, which came onshore on Thanksgiving, November 24, 2016. The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season will end November 30th.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2DOfZ0j

Preliminary summary of the tracks of all tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Basin during the 2018 hurricane season. Image via TheHurricaneEditorMaker/Wikimedia.

Hurricane season in the Atlantic basin, an area that includes the North Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico, ends on November 30th. Hurricanes during November are rare events, but they do occur and they can be deadly. In general, one November hurricane can be expected in the Atlantic basin every three or so years.

Hurricanes during November are rare because of the onset of cooler ocean temperatures and changes in wind shear in the Northern Hemisphere. These conditions are less favorable for the development of hurricanes. The hurricane season for the Atlantic basin runs from June 1 to November 30, which is the timeframe during which most hurricanes develop.

According to data compiled by NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory for the years 1851–2015, there have been 58 November hurricanes in total and only five that made landfall in the U.S. Now compare those numbers to the data for the month of September, which is the peak of hurricane season. During the same 164 year period, there were 395 September hurricanes and 107 that made landfall. That is a 6.8-fold decrease in the number of hurricanes that developed during those months, and a 21.4-fold decrease in the number that made landfall.

The Weather Channel, by using data collected since 1950, has estimated that a November hurricane will occur roughly once every three years. That article does a great job of summarizing some famous November hurricanes including Hurricane Kate and Hurricane Otto. Hurricane Kate made landfall just before Thanksgiving on November 21, 1985, near Mexico Beach, Florida. This represents the latest that a hurricane has made landfall according to modern recordkeeping. In long-term records dating back to 1851, the record for the latest landfall goes to Hurricane Otto, which came onshore at Nicaragua on Thanksgiving, November 24, 2016.

Together, the above data illustrate that November hurricanes are indeed a rare occurrence. However, these storms can be deadly and damaging.

Monthly frequency of tropical storms and hurricanes. Image via U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

To date, there have been 15 named storms including eight hurricanes and two major hurricanes (greater than a category 3) during the 2018 hurricane season. Quiet conditions are expected for the next several days, but don’t let your guard down just yet.

EarthSky’s 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

Bottom line: November hurricanes are rare events, but they do occur and they can be deadly. The record for the latest U.S. landfall is held by Hurricane Otto, which came onshore on Thanksgiving, November 24, 2016. The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season will end November 30th.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2DOfZ0j