This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Don’t feed the trolls. You’ve heard this advice before, but how can anyone sit on their hands when the trolls are just so … wrong? When you encounter a rude and inaccurate comment, often the best bet is to ignore it altogether. But if you’re feeling inspired, you can look beyond the toxicity and aim for a productive outcome. The thing you ought not do, however, is take the bait and lock horns with the offender. That’s a certain path to a lose-lose situation.

What would you do if confronted with this comment?

The High Priest of Environmental Causes Al Gore was out promoting his waste of cellulose In January, 2006 – when promoting his Oscar-winning (yes, Oscar-winning) documentary, An Inconvenient Truth – Gore declared that unless we took “drastic measures” to reduce greenhouse gasses, the world would reach a “point of no return” in a mere ten years. He called it a “true planetary emergency.” Well, the ten years passed today, we’re still here, and the climate activists have postponed the apocalypse. Again.

Tracing the spread of the myth

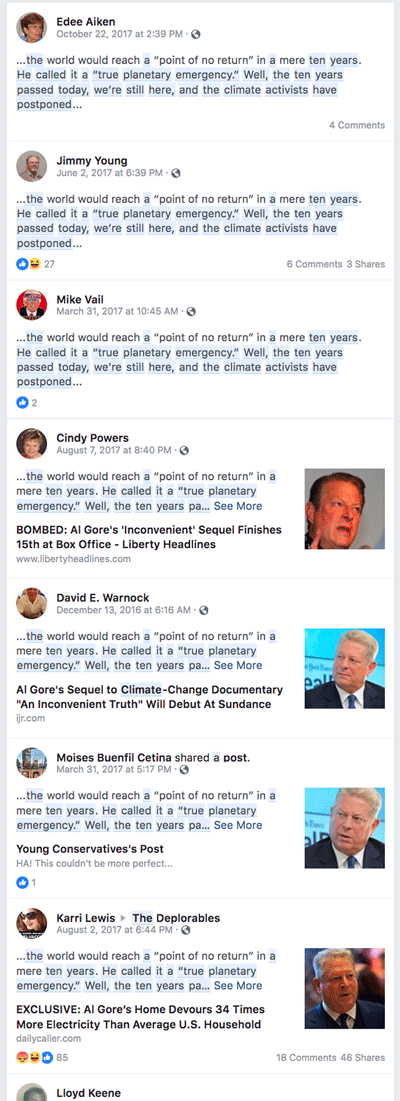

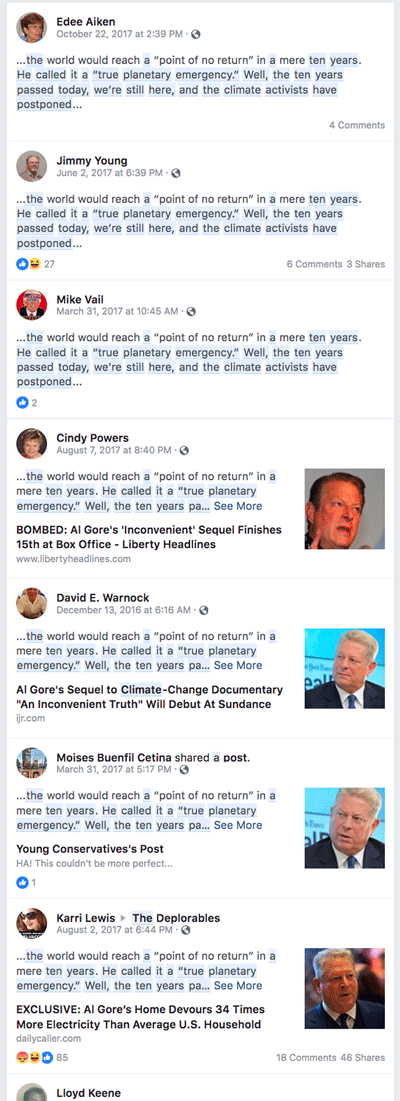

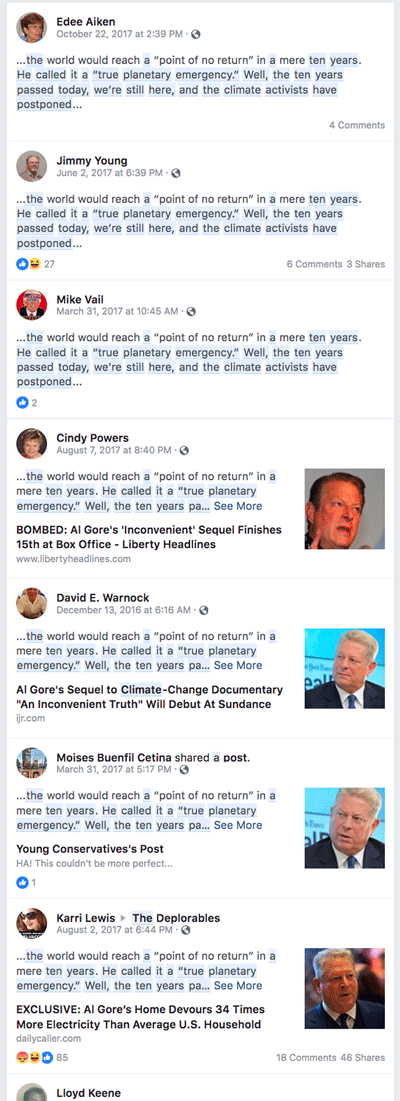

This gem appeared among a volley of comments on the Facebook page of a science advocacy organization. But the text was not the work of the commenter.

Further searching revealed the origin of this snippet. By plugging parts of the quote into a search engine and comparing the dates of publication, it was possible to track the spread of this quote across the web. The original idea appeared to emerge from a climate denial blog. A few weeks later, the same sentiment resurfaced, with obviously similar wording, in an article in the National Review, a conservative publication. From there, the quote has been circulated widely by climate contrarians, and in some cases, spread by what appear to be fake social media accounts.

This small example shows how misinformation germinates within dubious sources like anti-science blogs, then spreads into sympathetic media, and gets shared and re-shared outward from there. Welcome to the disinformation age.

Rebuttal Strategy #1 – Correct the science

The myth is mean-spirited, for sure. But is it true? Not even close, according to Scott Denning, professor of atmospheric science at Colorado State University. Denning’s faculty webpage details his expertise in carbon cycling and trace gas transport, but then offers an unusual credential: “takes special delight in engaging hostile audiences.”

Indeed, Denning has twice been a guest speaker at Heartland Institute conferences on climate change. Though he vehemently disagrees with Heartland’s stance on climate change, he reasons, “Ignoring climate contrarians has not made them go away.” Thus, he’s honed his methods to meaningfully engage people who dismiss climate science.

Denning’s first advice? Don’t fall into the trap of “fighting fire with fire.” Instead, he advises, “Find the nugget of a claim underneath the vitriol.”

It is not true that climate scientists predicted global catastrophe by 2018. Reading past the unhelpful tone, the logic behind this claim is as follows:

Premise 1: Emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases have continued and CO2 has continued to rise.

Premise 2: The consequences of the resulting warming so far aren’t all that bad.

Conclusion: Therefore global warming due to rising CO2 is not a problem and emissions can continue to rise without bound.

With the claim stripped of the inflammatory tone, it’s easy to examine in the light of day. The next step, says Denning, is to “dispatch with [the false claim] quickly and convincingly.”

The conclusion does not follow logically from the premises. CO2 and temperature have indeed continued to rise just as scientists predicted. Worse, the CO2 won’t go away when we eventually stop burning carbon, which is why the longer we wait, the more “drastic” measures we will have to take to avoid very serious damages to the world and our economy.

Denning explains, “I’m responding to the implication that there’s no urgency to reducing emissions. This is buried in the nastiness of the comment, but it’s the essence of the commenter’s message, so the thing we must refute.”

Inflammatory rhetoric intended to make you mad – so mad that you might not even catch the nonsensical claim. Denning describes it as “a multilayered trap,” because the comments are “personal, nasty, and inaccurate.”

The tone doesn’t make Denning shy away from addressing the comment, but it does shape the way he targets his rebuttal. “This kind of insulting rhetoric is precisely where we don’t want to go in the response.”

Strategy #2 – Expose the myth, misinformation, or fallacy

John Cook, research assistant professor at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, likes to use “parallel arguments” to help dismantle pervasive myths. In other words, take away everything to do with climate change and look at a situation similar to the one in the myth. At that point, it’s easy to “expose the poor logic in misinformation,” says Cook. To make his message memorable, Cook captures the parallel argument in a cartoon and a short rebuttal.

This climate myth argues that we haven’t felt climate impacts yet so CO2 emissions are not a problem. This is like jumping from a height and commenting halfway down that you haven’t felt any impact yet so everything’s fine. We are committing actions now that will have consequences in the future.

And for the record, we are experiencing climate impacts now. Heat waves are getting hotter and more frequent, droughts are intensifying, and warmer oceans are fueling hurricanes.

This myth supposes that we’re waiting for an apocalypse to arrive. But one needn’t look very far to realize the impacts of climate change are already at our doorsteps.

Strategy #3 – Engage in dialogue

De-escalation is a common technique in conflict resolution. While this climate myth intentionally stokes antagonism, Karin Tamerius illustrates how to walk the conversation back to practical turf.

You know, I think the word “emergency” probably means different things to different people. What would it take for you to see pollution as a planetary emergency?

Tamerius is no stranger to controversy. In fact, she routinely poses difficult questions and wrangles with members of her SMART Politics Facebook community. All the while, she’s using her background in political psychology to help people communicate more effectively on the topics of the day.

Tamerius prefers to begin her engagement with a question. “I’m trying to redirect attention from the credibility of one person (Al Gore), to what this person believes,” she says. “If I can find out what matters to them, I can address those concerns specifically.”

By steering the conversation away from the arena of partisan politics, Tamerius hopes to uncover deeper understanding. “After determining how they define ’emergency,’ I would turn to finding out how close they think we are to an emergency now,” she says. In the face of copy/paste talking points, probing how someone knows something can bring the conversation to a more rational place.

“The best way to change this person’s mind about who climate activists are and what they stand for is through example,” she says. “Attacks should be ignored or sidestepped, not engaged.”

Strategy #4 – Be persuasive

Rachel Molloy, of Redmond, Washington, is an art director and a determined volunteer who seeks to advance climate policy. She’s currently dedicating her time to build support for a Washington state ballot initiative that would implement statewide carbon pricing. Meanwhile, she’s also volunteering with the Climate Reality Project Leadership Corps. From knocking on doors, to visiting schools, to responding to never-ending false claims on social media, Molloy tirelessly strives to help people understand the need for climate action. And she’s no stranger to the false narratives that surround climate change.

As she considers the Al Gore myth, Molloy quickly targets the claim that impacts have not occurred. “This is demonstrably incorrect,” she writes. She starts by leveraging the power of personal experiences.

We are seeing signs of widespread planetary problems. This summer offers plenty of evidence for that.

My daughters had to wear face masks for the first time just to play outside in the smoke and falling ash, as our wildfire costs ballooned over budget, and our air quality fell among the worst in the world.

She then proceeds to a larger scale:

The National Weather Service called Hurricane Florence “the storm of a lifetime” for the Carolinas, and recently Hurricane Harvey dropped “historic amounts of rainfall” of more than 60 inches. The storms are getting bigger and our USA record-keepers are exactly who is warning us on that.

When responding to misinformation on social media, Molloy always references credible sources. She selects some of those sources with an eye toward their potential resonance with her audience. For example, for fiscal conservatives who might be swayed by the rising price tag of climate change, she shares NOAA’s tally of weather and climate disasters.

Whether you look at the number of events or the (inflation-adjusted) price tag, the upward trend of weather and climate disasters is clear. Source: NOAA.

Whether you look at the number of events or the (inflation-adjusted) price tag, the upward trend of weather and climate disasters is clear. Source: NOAA.

Molloy keeps a “stockpile” of sources that are likely to be viewed as credible by conservatives: Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, Exxon, and Chevron – all have supported taking action on climate change.

From Ronald Reagan to the 2017 Trump Administration National Climate Assessment … the science and the findings have been clear. Impacts from a warmer world are expensive and those costs are accelerating. 2017 just cost us +$300 billion, that’s some very expensive inaction, right here, right now.

Following a similar playbook as Dunning, Cook, and Tamerius, Molloy sidesteps the obvious attempts to drag the argument into the swamp. “Stay calm,” she advises. “I try to get the conversation back to credible sources and factual information at all times, and remain civil and patient throughout.”

Molloy understands that persuasion is a delicate balance, and she’s found that backing off the arguing and sharing some optimism about solutions can present an appealing détente. “Constantly be looking for that small offer of friendship or the crack in the door of someone willing to see that you are presenting a solid foundation that we can all stand on.”

The author is grateful to John Cook of George Mason University for his advice and recommendations on this project.

This series will continue to explore different facets of climate communication, while showcasing the voices of scientists, communicators, and everyday people.

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2RSn0jM

This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Don’t feed the trolls. You’ve heard this advice before, but how can anyone sit on their hands when the trolls are just so … wrong? When you encounter a rude and inaccurate comment, often the best bet is to ignore it altogether. But if you’re feeling inspired, you can look beyond the toxicity and aim for a productive outcome. The thing you ought not do, however, is take the bait and lock horns with the offender. That’s a certain path to a lose-lose situation.

What would you do if confronted with this comment?

The High Priest of Environmental Causes Al Gore was out promoting his waste of cellulose In January, 2006 – when promoting his Oscar-winning (yes, Oscar-winning) documentary, An Inconvenient Truth – Gore declared that unless we took “drastic measures” to reduce greenhouse gasses, the world would reach a “point of no return” in a mere ten years. He called it a “true planetary emergency.” Well, the ten years passed today, we’re still here, and the climate activists have postponed the apocalypse. Again.

Tracing the spread of the myth

This gem appeared among a volley of comments on the Facebook page of a science advocacy organization. But the text was not the work of the commenter.

Further searching revealed the origin of this snippet. By plugging parts of the quote into a search engine and comparing the dates of publication, it was possible to track the spread of this quote across the web. The original idea appeared to emerge from a climate denial blog. A few weeks later, the same sentiment resurfaced, with obviously similar wording, in an article in the National Review, a conservative publication. From there, the quote has been circulated widely by climate contrarians, and in some cases, spread by what appear to be fake social media accounts.

This small example shows how misinformation germinates within dubious sources like anti-science blogs, then spreads into sympathetic media, and gets shared and re-shared outward from there. Welcome to the disinformation age.

Rebuttal Strategy #1 – Correct the science

The myth is mean-spirited, for sure. But is it true? Not even close, according to Scott Denning, professor of atmospheric science at Colorado State University. Denning’s faculty webpage details his expertise in carbon cycling and trace gas transport, but then offers an unusual credential: “takes special delight in engaging hostile audiences.”

Indeed, Denning has twice been a guest speaker at Heartland Institute conferences on climate change. Though he vehemently disagrees with Heartland’s stance on climate change, he reasons, “Ignoring climate contrarians has not made them go away.” Thus, he’s honed his methods to meaningfully engage people who dismiss climate science.

Denning’s first advice? Don’t fall into the trap of “fighting fire with fire.” Instead, he advises, “Find the nugget of a claim underneath the vitriol.”

It is not true that climate scientists predicted global catastrophe by 2018. Reading past the unhelpful tone, the logic behind this claim is as follows:

Premise 1: Emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases have continued and CO2 has continued to rise.

Premise 2: The consequences of the resulting warming so far aren’t all that bad.

Conclusion: Therefore global warming due to rising CO2 is not a problem and emissions can continue to rise without bound.

With the claim stripped of the inflammatory tone, it’s easy to examine in the light of day. The next step, says Denning, is to “dispatch with [the false claim] quickly and convincingly.”

The conclusion does not follow logically from the premises. CO2 and temperature have indeed continued to rise just as scientists predicted. Worse, the CO2 won’t go away when we eventually stop burning carbon, which is why the longer we wait, the more “drastic” measures we will have to take to avoid very serious damages to the world and our economy.

Denning explains, “I’m responding to the implication that there’s no urgency to reducing emissions. This is buried in the nastiness of the comment, but it’s the essence of the commenter’s message, so the thing we must refute.”

Inflammatory rhetoric intended to make you mad – so mad that you might not even catch the nonsensical claim. Denning describes it as “a multilayered trap,” because the comments are “personal, nasty, and inaccurate.”

The tone doesn’t make Denning shy away from addressing the comment, but it does shape the way he targets his rebuttal. “This kind of insulting rhetoric is precisely where we don’t want to go in the response.”

Strategy #2 – Expose the myth, misinformation, or fallacy

John Cook, research assistant professor at the Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University, likes to use “parallel arguments” to help dismantle pervasive myths. In other words, take away everything to do with climate change and look at a situation similar to the one in the myth. At that point, it’s easy to “expose the poor logic in misinformation,” says Cook. To make his message memorable, Cook captures the parallel argument in a cartoon and a short rebuttal.

This climate myth argues that we haven’t felt climate impacts yet so CO2 emissions are not a problem. This is like jumping from a height and commenting halfway down that you haven’t felt any impact yet so everything’s fine. We are committing actions now that will have consequences in the future.

And for the record, we are experiencing climate impacts now. Heat waves are getting hotter and more frequent, droughts are intensifying, and warmer oceans are fueling hurricanes.

This myth supposes that we’re waiting for an apocalypse to arrive. But one needn’t look very far to realize the impacts of climate change are already at our doorsteps.

Strategy #3 – Engage in dialogue

De-escalation is a common technique in conflict resolution. While this climate myth intentionally stokes antagonism, Karin Tamerius illustrates how to walk the conversation back to practical turf.

You know, I think the word “emergency” probably means different things to different people. What would it take for you to see pollution as a planetary emergency?

Tamerius is no stranger to controversy. In fact, she routinely poses difficult questions and wrangles with members of her SMART Politics Facebook community. All the while, she’s using her background in political psychology to help people communicate more effectively on the topics of the day.

Tamerius prefers to begin her engagement with a question. “I’m trying to redirect attention from the credibility of one person (Al Gore), to what this person believes,” she says. “If I can find out what matters to them, I can address those concerns specifically.”

By steering the conversation away from the arena of partisan politics, Tamerius hopes to uncover deeper understanding. “After determining how they define ’emergency,’ I would turn to finding out how close they think we are to an emergency now,” she says. In the face of copy/paste talking points, probing how someone knows something can bring the conversation to a more rational place.

“The best way to change this person’s mind about who climate activists are and what they stand for is through example,” she says. “Attacks should be ignored or sidestepped, not engaged.”

Strategy #4 – Be persuasive

Rachel Molloy, of Redmond, Washington, is an art director and a determined volunteer who seeks to advance climate policy. She’s currently dedicating her time to build support for a Washington state ballot initiative that would implement statewide carbon pricing. Meanwhile, she’s also volunteering with the Climate Reality Project Leadership Corps. From knocking on doors, to visiting schools, to responding to never-ending false claims on social media, Molloy tirelessly strives to help people understand the need for climate action. And she’s no stranger to the false narratives that surround climate change.

As she considers the Al Gore myth, Molloy quickly targets the claim that impacts have not occurred. “This is demonstrably incorrect,” she writes. She starts by leveraging the power of personal experiences.

We are seeing signs of widespread planetary problems. This summer offers plenty of evidence for that.

My daughters had to wear face masks for the first time just to play outside in the smoke and falling ash, as our wildfire costs ballooned over budget, and our air quality fell among the worst in the world.

She then proceeds to a larger scale:

The National Weather Service called Hurricane Florence “the storm of a lifetime” for the Carolinas, and recently Hurricane Harvey dropped “historic amounts of rainfall” of more than 60 inches. The storms are getting bigger and our USA record-keepers are exactly who is warning us on that.

When responding to misinformation on social media, Molloy always references credible sources. She selects some of those sources with an eye toward their potential resonance with her audience. For example, for fiscal conservatives who might be swayed by the rising price tag of climate change, she shares NOAA’s tally of weather and climate disasters.

Whether you look at the number of events or the (inflation-adjusted) price tag, the upward trend of weather and climate disasters is clear. Source: NOAA.

Whether you look at the number of events or the (inflation-adjusted) price tag, the upward trend of weather and climate disasters is clear. Source: NOAA.

Molloy keeps a “stockpile” of sources that are likely to be viewed as credible by conservatives: Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, Exxon, and Chevron – all have supported taking action on climate change.

From Ronald Reagan to the 2017 Trump Administration National Climate Assessment … the science and the findings have been clear. Impacts from a warmer world are expensive and those costs are accelerating. 2017 just cost us +$300 billion, that’s some very expensive inaction, right here, right now.

Following a similar playbook as Dunning, Cook, and Tamerius, Molloy sidesteps the obvious attempts to drag the argument into the swamp. “Stay calm,” she advises. “I try to get the conversation back to credible sources and factual information at all times, and remain civil and patient throughout.”

Molloy understands that persuasion is a delicate balance, and she’s found that backing off the arguing and sharing some optimism about solutions can present an appealing détente. “Constantly be looking for that small offer of friendship or the crack in the door of someone willing to see that you are presenting a solid foundation that we can all stand on.”

The author is grateful to John Cook of George Mason University for his advice and recommendations on this project.

This series will continue to explore different facets of climate communication, while showcasing the voices of scientists, communicators, and everyday people.

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2RSn0jM

Now designated as California’s deadliest fire, the still-raging Camp Fire by November 13 had led to 42 deaths, with many residents still unaccounted for and more than 7,000 structures destroyed. (Image credit: NASA)

Now designated as California’s deadliest fire, the still-raging Camp Fire by November 13 had led to 42 deaths, with many residents still unaccounted for and more than 7,000 structures destroyed. (Image credit: NASA) Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Credit: Image by Karin Kirk.

Whether you look at the number of events or the (inflation-adjusted) price tag, the upward trend of weather and climate disasters is clear. Source:

Whether you look at the number of events or the (inflation-adjusted) price tag, the upward trend of weather and climate disasters is clear. Source: