A selection of new climate related research articles is shown below.

Climate change impacts

Mankind

Altered Disease Risk from Climate Change (A special issue in EcoHealth)

Investigation on fatal accidents in Chinese construction industry between 2004 and 2016

Drivers of diversity in human thermal perception – A review for holistic comfort models (open access)

Quantifying the effect of rain events on outdoor thermal comfort in a high-density city, Hong Kong

Bridging Research and Policy on Climate Change and Conflict

Climate change implications for irrigation and groundwater in the Republican River Basin, USA (open access)

Using impact response surfaces to analyse the likelihood of impacts on crop yield under probabilistic climate change (open access)

Are agricultural researchers working on the right crops to enable food and nutrition security under future climates? (open access)

Machine learning methods for crop yield prediction and climate change impact assessment in agriculture (open access)

A Reappraisal of the Thermal Growing Season Length across Europe

Enough is enough: how West African farmers judge water sufficiency

Biosphere

The influence of climatic legacies on the distribution of dryland biocrust communities

The response of boreal peatland community composition and NDVI to hydrologic change, warming, and elevated carbon dioxide (open access)

Functional reorganization of marine fish nurseries under climate warming

Climate change threatens central Tunisian nut orchards

Tree rings reveal long-term changes in growth resilience in Southern European riparian forests

Tree resilience to drought increases in the Tibetan Plateau (open access)

Miami heat: urban heat islands influence the thermal suitability of habitats for ectotherms

Other impacts

Forest fire hazard during 2000–2016 in Zhejiang province of the typical subtropical region, China

Evaluating regional resiliency of coastal wetlands to sea level rise through hypsometry‐based modeling (open access)

Climate change mitigation

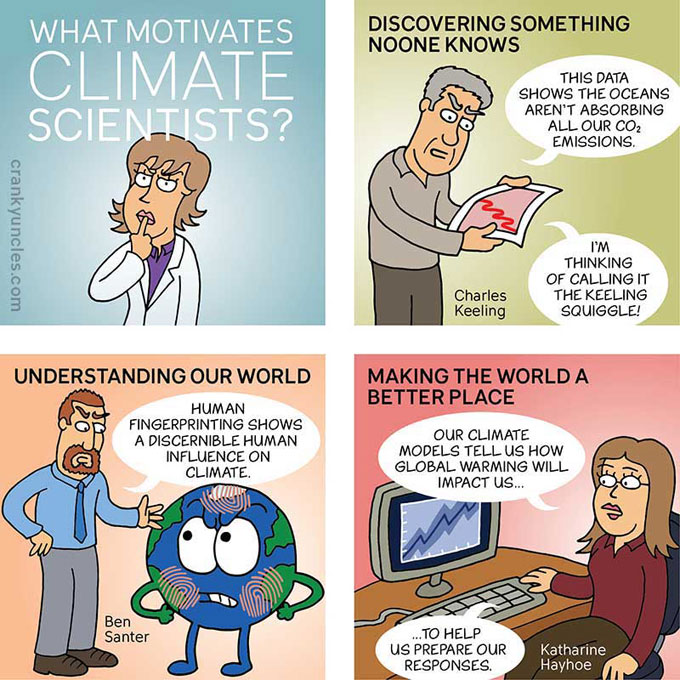

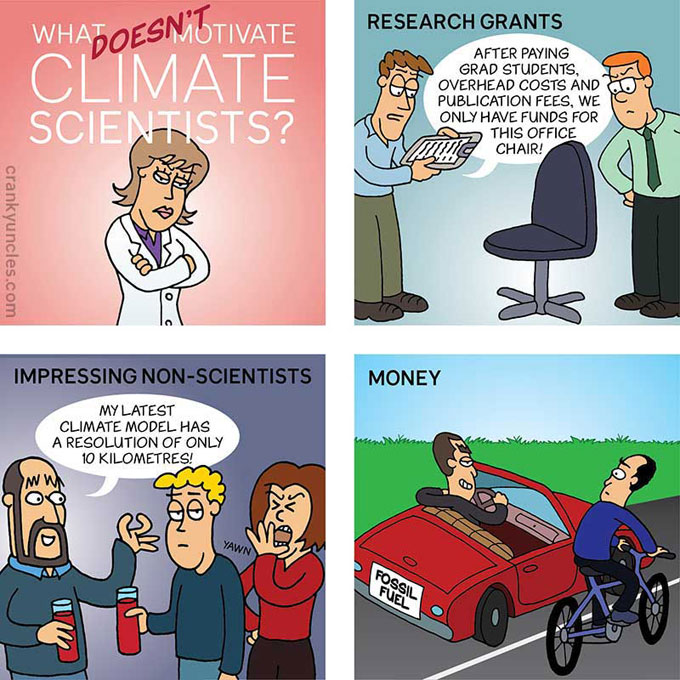

Climate change communication

Educational Backgrounds of TV Weathercasters (open access)

Climate Policy

Effect of carbon tax on the industrial competitiveness of Chongqing, China

Energy production

Emission savings

Geoengineering

Targeting carbon dioxide removal in the European Union (open access)

Climate change

East Asian climate under global warming: understanding and projection

Temperature, precipitation, wind

ENSO-related Global Ocean Heat Content Variations

The importance of unresolved biases in 20th century sea-surface temperature observations (open access)

Quantifying the Importance of Rapid Adjustments for Global Precipitation Changes (open access)

Extreme events

Spatiotemporal Analysis of Near-Miss Violent Tornadoes in the United States

On the decadal predictability of the frequency of flood events across the U.S. Midwest

Flood mapping under uncertainty: a case study in the Canadian prairies

Characteristics of meteorological droughts in northwestern India

Mechanisms and Early Warning of Drought Disasters: An Experimental Drought Meteorology Research over China (DroughtEX_China) (open access)

Projecting changes in societally‐impactful northeastern U.S. snowstorms

Forcings and feedbacks

Rapid and reliable assessment of methane impacts on climate (open access)

Effective radiative forcing in the aerosol–climate model CAM5.3-MARC-ARG (open access)

Additional global climate cooling by clouds due to ice crystal complexity (open access)

Characterizing uncertainties in the ESA-CCI land cover map of the epoch 2010 and their impacts on MPI-ESM climate simulations (open access)

Cryosphere

Impact of the recent atmospheric circulation change in summer on the future surface mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet (open access)

Basal control of supraglacial meltwater catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet (open access)

Detecting soil freeze/thaw onsets in Alaska using SMAP and ASCAT data

Improving Met Office seasonal predictions of Arctic sea ice using assimilation of CryoSat-2 thickness (open access)

Widespread and accelerated decrease of observed mean and extreme snow depth over Europe

Basal ice formation in snow cover in Northern Finland between 1948 and 2016 (open access)

Hydrosphere

Evolution of 21st Century Sea‐level Rise Projections (open access)

Climate change expectations in the upper Tigris River basin, Turkey

Cooling and freshening of the West Spitsbergen Current by shelf‐origin cold core lenses

Atmospheric and oceanic circulation

Performance of CMIP5 models in the simulation of Indian summer monsoon

A robust constraint on the temperature and height of the extratropical tropopause

West African Monsoon: current state and future projections in a high-resolution AGCM (open access)

Reassessing the Role of the Indo‐Pacific in the Ocean's Global Overturning Circulation

Carbon and nitrogen cycles

Nitrous oxide emissions from inland waters: Are IPCC estimates too high?

Other papers

General climate science

100 Years Later: Reflecting on Alfred Wegener’s Contributions to Tornado Research in Europe (open access)

Heat‐engine and entropy‐production analyses of the world ocean

Palaeoclimatology

Other environmental issues

Trends in air pollutants and health impacts in three Swedish cities over the past three decades (open access)

Public Attention to Natural Hazard Warnings in Social Media in China

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2qCEbu0

A selection of new climate related research articles is shown below.

Climate change impacts

Mankind

Altered Disease Risk from Climate Change (A special issue in EcoHealth)

Investigation on fatal accidents in Chinese construction industry between 2004 and 2016

Drivers of diversity in human thermal perception – A review for holistic comfort models (open access)

Quantifying the effect of rain events on outdoor thermal comfort in a high-density city, Hong Kong

Bridging Research and Policy on Climate Change and Conflict

Climate change implications for irrigation and groundwater in the Republican River Basin, USA (open access)

Using impact response surfaces to analyse the likelihood of impacts on crop yield under probabilistic climate change (open access)

Are agricultural researchers working on the right crops to enable food and nutrition security under future climates? (open access)

Machine learning methods for crop yield prediction and climate change impact assessment in agriculture (open access)

A Reappraisal of the Thermal Growing Season Length across Europe

Enough is enough: how West African farmers judge water sufficiency

Biosphere

The influence of climatic legacies on the distribution of dryland biocrust communities

The response of boreal peatland community composition and NDVI to hydrologic change, warming, and elevated carbon dioxide (open access)

Functional reorganization of marine fish nurseries under climate warming

Climate change threatens central Tunisian nut orchards

Tree rings reveal long-term changes in growth resilience in Southern European riparian forests

Tree resilience to drought increases in the Tibetan Plateau (open access)

Miami heat: urban heat islands influence the thermal suitability of habitats for ectotherms

Other impacts

Forest fire hazard during 2000–2016 in Zhejiang province of the typical subtropical region, China

Evaluating regional resiliency of coastal wetlands to sea level rise through hypsometry‐based modeling (open access)

Climate change mitigation

Climate change communication

Educational Backgrounds of TV Weathercasters (open access)

Climate Policy

Effect of carbon tax on the industrial competitiveness of Chongqing, China

Energy production

Emission savings

Geoengineering

Targeting carbon dioxide removal in the European Union (open access)

Climate change

East Asian climate under global warming: understanding and projection

Temperature, precipitation, wind

ENSO-related Global Ocean Heat Content Variations

The importance of unresolved biases in 20th century sea-surface temperature observations (open access)

Quantifying the Importance of Rapid Adjustments for Global Precipitation Changes (open access)

Extreme events

Spatiotemporal Analysis of Near-Miss Violent Tornadoes in the United States

On the decadal predictability of the frequency of flood events across the U.S. Midwest

Flood mapping under uncertainty: a case study in the Canadian prairies

Characteristics of meteorological droughts in northwestern India

Mechanisms and Early Warning of Drought Disasters: An Experimental Drought Meteorology Research over China (DroughtEX_China) (open access)

Projecting changes in societally‐impactful northeastern U.S. snowstorms

Forcings and feedbacks

Rapid and reliable assessment of methane impacts on climate (open access)

Effective radiative forcing in the aerosol–climate model CAM5.3-MARC-ARG (open access)

Additional global climate cooling by clouds due to ice crystal complexity (open access)

Characterizing uncertainties in the ESA-CCI land cover map of the epoch 2010 and their impacts on MPI-ESM climate simulations (open access)

Cryosphere

Impact of the recent atmospheric circulation change in summer on the future surface mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet (open access)

Basal control of supraglacial meltwater catchments on the Greenland Ice Sheet (open access)

Detecting soil freeze/thaw onsets in Alaska using SMAP and ASCAT data

Improving Met Office seasonal predictions of Arctic sea ice using assimilation of CryoSat-2 thickness (open access)

Widespread and accelerated decrease of observed mean and extreme snow depth over Europe

Basal ice formation in snow cover in Northern Finland between 1948 and 2016 (open access)

Hydrosphere

Evolution of 21st Century Sea‐level Rise Projections (open access)

Climate change expectations in the upper Tigris River basin, Turkey

Cooling and freshening of the West Spitsbergen Current by shelf‐origin cold core lenses

Atmospheric and oceanic circulation

Performance of CMIP5 models in the simulation of Indian summer monsoon

A robust constraint on the temperature and height of the extratropical tropopause

West African Monsoon: current state and future projections in a high-resolution AGCM (open access)

Reassessing the Role of the Indo‐Pacific in the Ocean's Global Overturning Circulation

Carbon and nitrogen cycles

Nitrous oxide emissions from inland waters: Are IPCC estimates too high?

Other papers

General climate science

100 Years Later: Reflecting on Alfred Wegener’s Contributions to Tornado Research in Europe (open access)

Heat‐engine and entropy‐production analyses of the world ocean

Palaeoclimatology

Other environmental issues

Trends in air pollutants and health impacts in three Swedish cities over the past three decades (open access)

Public Attention to Natural Hazard Warnings in Social Media in China

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2qCEbu0

Image by Karin Kirk.

Image by Karin Kirk.