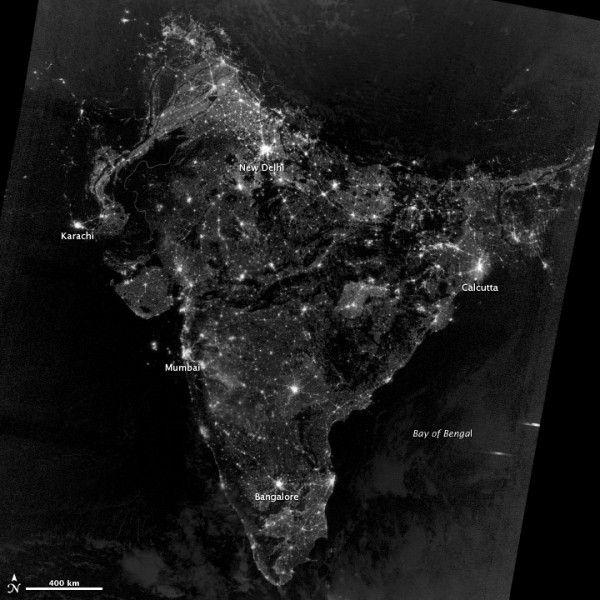

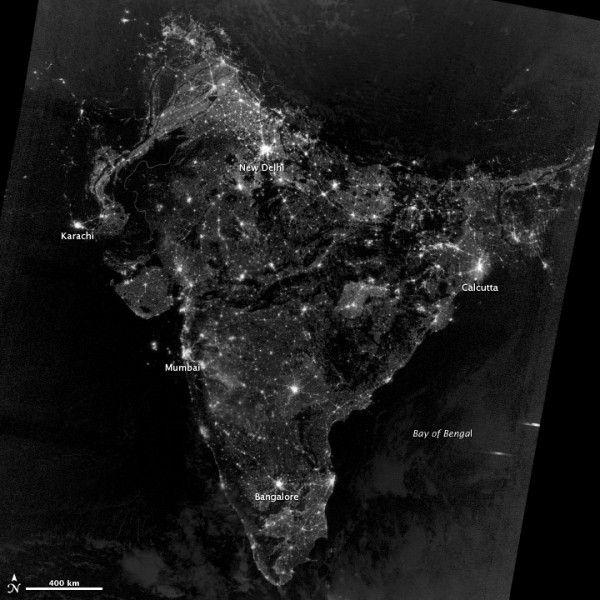

This image of India has been circulating on the Internet for years. Some claim it shows India during Diwali, but it doesn’t. Yes, it’s a real satellite image, but it’s a composite, with several different years of lighting combined together. Image via U.S. Defense Meteorological Satellite Program.

This week is Diwali in India, and that means it’s time for the image above – purportedly showing India at the time of Diwali, from space – to circulate on social media. In fact, this image been circulating all year. The Indian news website The Quint started tracking it as early as February 2018, and said:

If we look back in history to find out the biggest fake stories that have been circulated among Indians, there’s only one that can top the theory that Ricky Ponting had a spring attached to his bat in ICC World Cup 2003 Final, and that is the so-called satellite image of the Indian sub-continent taken on Diwali night by NASA.

Just like Diwali is incomplete without buying new clothes, playing cards with your family and lighting up the house, it is also incomplete, in the age of social media, without someone, year after year, sharing this fake image.

The 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

So … what is this image? It doesn’t show what it claims to show; that is, it doesn’t show India on a single night during the Diwali festival.

This image does come from satellite data. It’s based on data from U.S. Defense Meteorological Satellite Program satellites, and it’s a color-composite created in 2003 by scientist Chris Elvidge to highlight population growth over time. In this image, white areas show city lights that were visible prior to 1992, while blue, green, and red shades indicate city lights that became visible in 1992, 1998, and 2003 respectively.

Now, here’s a real image of India during Diwali:

Real satellite image of India, taken during a Diwali festival. Image acquired November 12, 2012, via NASA’s Earth Observatory.

The image above – which has been artificially brightened – shows what India looked like from space on a night during Diwali, in this case in November, 2012. It’s what India looks like from space on a typical Diwali night … or on any night in India, according to NASA. In fact, according to NASA, the extra light produced during Diwali is so subtle that space images don’t show it.

The image above is from a NASA satellite known as Suomi NPP, for National Polar-orbiting Partnership. An instrument carried on this satellite – which detects light in a range of wavelengths from green to near-infrared – acquired this image in a single night. The image has been brightened to make the city lights easier to distinguish.

Most of the bright areas are cities and towns in India, which is home to more than 1.3 billion people and has 53 cities with populations over 1 million.

Cities in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan are also visible near the edges of the image above.

Diwali fireworks. A time-lapse composite of pictures taken on October 30, 2016, from 7 to 11 p.m. by Abhinav Singhai in New Delhi, India.

The Hindu festival of Diwali celebrates the victory of Good over the Evil and Light over Darkness. It also marks the beginning of the Hindu New Year. In 2018, Diwali falls on November 7, corresponding with November’s new moon at 16:02 UTC on that date.

This darkest, new moon night is called Kartika in the Hindu Lunisolar calendar – all the better to see the fireworks and enjoy the symbolic burning of lamps and candles. Diwali is a major holiday in India, and it’s also celebrated by millions across the world, from India, Nepal and Malaysia and on into the west (for example, in the UK).

It marks the homecoming of the God Lord Ram after vanquishing the demon king Ravana.

Lighting lamps, candles, and fireworks are a big part of Diwali. It’s a celebration of light! Can you see those celebratory lights from space? No. But you can enjoy it all the same.

Happy Diwali to all who celebrate it!

Bottom line: Diwali is a festival of light, and a persistent internet hoax shows a fake image of “India during Diwali, from space.” NASA says the extra light so many enjoy during Diwali would not be visible from space.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2PFh2We

This image of India has been circulating on the Internet for years. Some claim it shows India during Diwali, but it doesn’t. Yes, it’s a real satellite image, but it’s a composite, with several different years of lighting combined together. Image via U.S. Defense Meteorological Satellite Program.

This week is Diwali in India, and that means it’s time for the image above – purportedly showing India at the time of Diwali, from space – to circulate on social media. In fact, this image been circulating all year. The Indian news website The Quint started tracking it as early as February 2018, and said:

If we look back in history to find out the biggest fake stories that have been circulated among Indians, there’s only one that can top the theory that Ricky Ponting had a spring attached to his bat in ICC World Cup 2003 Final, and that is the so-called satellite image of the Indian sub-continent taken on Diwali night by NASA.

Just like Diwali is incomplete without buying new clothes, playing cards with your family and lighting up the house, it is also incomplete, in the age of social media, without someone, year after year, sharing this fake image.

The 2019 lunar calendars are here! Order yours before they’re gone. Makes a great gift.

So … what is this image? It doesn’t show what it claims to show; that is, it doesn’t show India on a single night during the Diwali festival.

This image does come from satellite data. It’s based on data from U.S. Defense Meteorological Satellite Program satellites, and it’s a color-composite created in 2003 by scientist Chris Elvidge to highlight population growth over time. In this image, white areas show city lights that were visible prior to 1992, while blue, green, and red shades indicate city lights that became visible in 1992, 1998, and 2003 respectively.

Now, here’s a real image of India during Diwali:

Real satellite image of India, taken during a Diwali festival. Image acquired November 12, 2012, via NASA’s Earth Observatory.

The image above – which has been artificially brightened – shows what India looked like from space on a night during Diwali, in this case in November, 2012. It’s what India looks like from space on a typical Diwali night … or on any night in India, according to NASA. In fact, according to NASA, the extra light produced during Diwali is so subtle that space images don’t show it.

The image above is from a NASA satellite known as Suomi NPP, for National Polar-orbiting Partnership. An instrument carried on this satellite – which detects light in a range of wavelengths from green to near-infrared – acquired this image in a single night. The image has been brightened to make the city lights easier to distinguish.

Most of the bright areas are cities and towns in India, which is home to more than 1.3 billion people and has 53 cities with populations over 1 million.

Cities in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan are also visible near the edges of the image above.

Diwali fireworks. A time-lapse composite of pictures taken on October 30, 2016, from 7 to 11 p.m. by Abhinav Singhai in New Delhi, India.

The Hindu festival of Diwali celebrates the victory of Good over the Evil and Light over Darkness. It also marks the beginning of the Hindu New Year. In 2018, Diwali falls on November 7, corresponding with November’s new moon at 16:02 UTC on that date.

This darkest, new moon night is called Kartika in the Hindu Lunisolar calendar – all the better to see the fireworks and enjoy the symbolic burning of lamps and candles. Diwali is a major holiday in India, and it’s also celebrated by millions across the world, from India, Nepal and Malaysia and on into the west (for example, in the UK).

It marks the homecoming of the God Lord Ram after vanquishing the demon king Ravana.

Lighting lamps, candles, and fireworks are a big part of Diwali. It’s a celebration of light! Can you see those celebratory lights from space? No. But you can enjoy it all the same.

Happy Diwali to all who celebrate it!

Bottom line: Diwali is a festival of light, and a persistent internet hoax shows a fake image of “India during Diwali, from space.” NASA says the extra light so many enjoy during Diwali would not be visible from space.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2PFh2We