The sunset has been making its way north, as illustrated in this 2016 photo composite by Abhijit Juvekar.

The June solstice – your signal to celebrate summer in the Northern Hemisphere and winter in the Southern Hemisphere – is coming up on June 21, 2018, at 10:07 UTC. That’s 5:97 a.m. CDT in North America on June 21. Translate UTC to your time. For us in the Northern Hemisphere, this solstice marks the longest day of the year. Early dawns. Long days. Late sunsets. Short nights. The sun at its height each day, as it crosses the sky. Meanwhile, south of the equator, winter begins.

What is a solstice? Ancient cultures knew that the sun’s path across the sky, the length of daylight, and the location of the sunrise and sunset all shifted in a regular way throughout the year.

They built monuments, such as Stonehenge, to follow the sun’s yearly progress.

Today, we know that the solstice is an astronomical event, caused by Earth’s tilt on its axis and its motion in orbit around the sun.

Because Earth doesn’t orbit upright. Instead, our world is tilted on its axis by 23-and-a-half degrees, Earth’s Northern and Southern Hemispheres trade places in receiving the sun’s light and warmth most directly.

At the June solstice, Earth is positioned in its orbit so that our world’s North Pole is leaning most toward the sun. As seen from Earth, the sun is directly overhead at noon 23 1/2 degrees north of the equator, at an imaginary line encircling the globe known as the Tropic of Cancer – named after the constellation Cancer the Crab. This is as far north as the sun ever gets.

All locations north of the equator have days longer than 12 hours at the June solstice. Meanwhile, all locations south of the equator have days shorter than 12 hours.

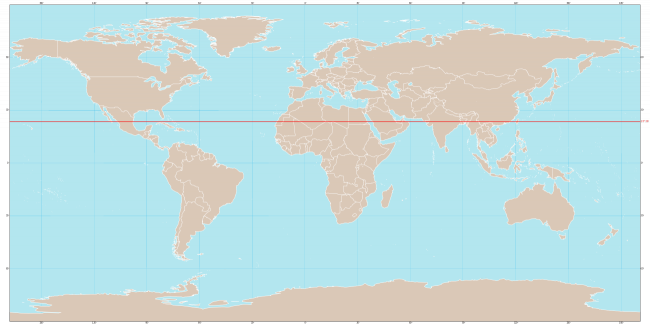

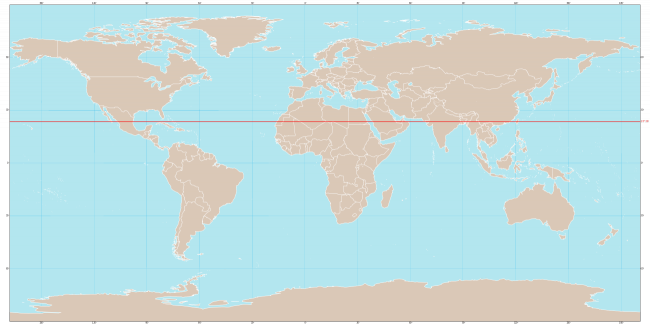

The red line shows the Tropic of Cancer. As seen from this line of latitude, the sun appears overhead at noon on the June solstice. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

When is the solstice where I live? The solstice takes place place on June 21, 2018 at 10:07 UTC. That’s 5:07 a.m. CDT in North America on June 20.

A solstice happens at the same instant for all of us, everywhere on Earth. To find the time of the solstice in your location, you have to translate to your time zone.

Here’s an example of how to do that. In the central United States, for those of us using Central Daylight Time, we subtract five hours from Universal Time. That’s how we get 5:07 a.m. CDT as the time of the 2018 June solstice (10:07 UTC on June 21 minus 5 equals 5:07 a.m. CDT on June 21).

Want to know the time in your location? Check out EarthSky’s article How do I translate Universal Time into my time? And just remember: you’re translating from 10:07 UTC, June 21.

Where should I look to see signs of the solstice in nature? Everywhere. For all of Earth’s creatures, nothing is so fundamental as the length of the day. After all, the sun is the ultimate source of almost all light and warmth on Earth’s surface.

If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, you might notice the early dawns and late sunsets, and the high arc of the sun across the sky each day. You might see how high the sun appears in the sky at local noon. And be sure to look at your noontime shadow. Around the time of the solstice, it’s your shortest noontime shadow of the year.

If you’re a person who’s tuned in to the out-of-doors, you know the peaceful, comforting feeling that accompanies these signs and signals of the year’s longest day.

Watching the solstice sunrise. Photo via Sarah Little-Knitwitz, Glastonbury Tor, Somerset, U.K.

Is the solstice the first day of summer? No world body has designated an official day to start each new season, and different schools of thought or traditions define the seasons in different ways.

In meteorology, for example, summer begins on June 1. And every school child knows that summer starts when the last school bell of the year rings.

Yet today is perhaps the most widely recognized day upon which summer begins in the Northern Hemisphere and upon which winter begins on the southern half of Earth’s globe. There’s nothing official about it, but it’s such a long-held tradition that we all recognize it to be so.

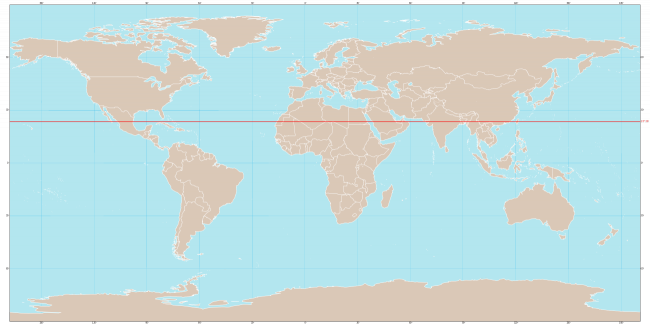

Day and night sides of Earth at the instant of June 2018 solstice (2018 June 21 at 10:07 UTC). It’s sunrise in the Americas, noon in Africa, and sunset in Japan and Indonesia. Worldwide map via the US Naval Observatory.

It has been universal among humans to treasure this time of warmth and light.

For us in the modern world, the solstice is a time to recall the reverence and understanding that early people had for the sky. Some 5,000 years ago, people placed huge stones in a circle on a broad plain in what’s now England and aligned them with the June solstice sunrise.

We may never comprehend the full significance of Stonehenge. But we do know that knowledge of this sort wasn’t isolated to just one part of the world. Around the same time Stonehenge was being constructed in England, two great pyramids and then the Sphinx were built on Egyptian sands. If you stood at the Sphinx on the summer solstice and gazed toward the two pyramids, you’d see the sun set exactly between them.

How does it end up hotter later in the summer, if June has the longest day? People often ask:

If the June solstice brings the longest day, why do we experience the hottest weather in late July and August?

This effect is called the lag of the seasons. It’s the same reason it’s hotter in mid-afternoon than at noontime. Earth just takes a while to warm up after a long winter. Even in June, ice and snow still blanket the ground in some places. The sun has to melt the ice – and warm the oceans – and then we feel the most sweltering summer heat.

Ice and snow have been melting since spring began. Meltwater and rainwater have been percolating down through snow on tops of glaciers.

But the runoff from glaciers isn’t as great now as it’ll be in another month, even though sunlight is striking the northern hemisphere most directly around now.

So wait another month for the hottest weather. It’ll come when the days are already beginning to shorten again, as Earth continues to move in orbit around the sun, bringing us closer to another winter.

And so the cycle continues.

Hello summer solstice!

Bottom line: The 2018 June happens on June 21 at 10:07 UTC. That’s 5:07 a.m. CDT in North America. This solstice – which marks the beginning of summer in the Northern Hemisphere – marks the sun’s most northerly point in Earth’s sky. It’s an event celebrated by people throughout the ages.

Visit EarthSky Tonight for easy-to-use night sky charts and info. Updated daily.

Celebrate the summer solstice as the Chinese philosophers did

Why the hottest weather isn’t on the longest day

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/1fl9JNp

The sunset has been making its way north, as illustrated in this 2016 photo composite by Abhijit Juvekar.

The June solstice – your signal to celebrate summer in the Northern Hemisphere and winter in the Southern Hemisphere – is coming up on June 21, 2018, at 10:07 UTC. That’s 5:97 a.m. CDT in North America on June 21. Translate UTC to your time. For us in the Northern Hemisphere, this solstice marks the longest day of the year. Early dawns. Long days. Late sunsets. Short nights. The sun at its height each day, as it crosses the sky. Meanwhile, south of the equator, winter begins.

What is a solstice? Ancient cultures knew that the sun’s path across the sky, the length of daylight, and the location of the sunrise and sunset all shifted in a regular way throughout the year.

They built monuments, such as Stonehenge, to follow the sun’s yearly progress.

Today, we know that the solstice is an astronomical event, caused by Earth’s tilt on its axis and its motion in orbit around the sun.

Because Earth doesn’t orbit upright. Instead, our world is tilted on its axis by 23-and-a-half degrees, Earth’s Northern and Southern Hemispheres trade places in receiving the sun’s light and warmth most directly.

At the June solstice, Earth is positioned in its orbit so that our world’s North Pole is leaning most toward the sun. As seen from Earth, the sun is directly overhead at noon 23 1/2 degrees north of the equator, at an imaginary line encircling the globe known as the Tropic of Cancer – named after the constellation Cancer the Crab. This is as far north as the sun ever gets.

All locations north of the equator have days longer than 12 hours at the June solstice. Meanwhile, all locations south of the equator have days shorter than 12 hours.

The red line shows the Tropic of Cancer. As seen from this line of latitude, the sun appears overhead at noon on the June solstice. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

When is the solstice where I live? The solstice takes place place on June 21, 2018 at 10:07 UTC. That’s 5:07 a.m. CDT in North America on June 20.

A solstice happens at the same instant for all of us, everywhere on Earth. To find the time of the solstice in your location, you have to translate to your time zone.

Here’s an example of how to do that. In the central United States, for those of us using Central Daylight Time, we subtract five hours from Universal Time. That’s how we get 5:07 a.m. CDT as the time of the 2018 June solstice (10:07 UTC on June 21 minus 5 equals 5:07 a.m. CDT on June 21).

Want to know the time in your location? Check out EarthSky’s article How do I translate Universal Time into my time? And just remember: you’re translating from 10:07 UTC, June 21.

Where should I look to see signs of the solstice in nature? Everywhere. For all of Earth’s creatures, nothing is so fundamental as the length of the day. After all, the sun is the ultimate source of almost all light and warmth on Earth’s surface.

If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, you might notice the early dawns and late sunsets, and the high arc of the sun across the sky each day. You might see how high the sun appears in the sky at local noon. And be sure to look at your noontime shadow. Around the time of the solstice, it’s your shortest noontime shadow of the year.

If you’re a person who’s tuned in to the out-of-doors, you know the peaceful, comforting feeling that accompanies these signs and signals of the year’s longest day.

Watching the solstice sunrise. Photo via Sarah Little-Knitwitz, Glastonbury Tor, Somerset, U.K.

Is the solstice the first day of summer? No world body has designated an official day to start each new season, and different schools of thought or traditions define the seasons in different ways.

In meteorology, for example, summer begins on June 1. And every school child knows that summer starts when the last school bell of the year rings.

Yet today is perhaps the most widely recognized day upon which summer begins in the Northern Hemisphere and upon which winter begins on the southern half of Earth’s globe. There’s nothing official about it, but it’s such a long-held tradition that we all recognize it to be so.

Day and night sides of Earth at the instant of June 2018 solstice (2018 June 21 at 10:07 UTC). It’s sunrise in the Americas, noon in Africa, and sunset in Japan and Indonesia. Worldwide map via the US Naval Observatory.

It has been universal among humans to treasure this time of warmth and light.

For us in the modern world, the solstice is a time to recall the reverence and understanding that early people had for the sky. Some 5,000 years ago, people placed huge stones in a circle on a broad plain in what’s now England and aligned them with the June solstice sunrise.

We may never comprehend the full significance of Stonehenge. But we do know that knowledge of this sort wasn’t isolated to just one part of the world. Around the same time Stonehenge was being constructed in England, two great pyramids and then the Sphinx were built on Egyptian sands. If you stood at the Sphinx on the summer solstice and gazed toward the two pyramids, you’d see the sun set exactly between them.

How does it end up hotter later in the summer, if June has the longest day? People often ask:

If the June solstice brings the longest day, why do we experience the hottest weather in late July and August?

This effect is called the lag of the seasons. It’s the same reason it’s hotter in mid-afternoon than at noontime. Earth just takes a while to warm up after a long winter. Even in June, ice and snow still blanket the ground in some places. The sun has to melt the ice – and warm the oceans – and then we feel the most sweltering summer heat.

Ice and snow have been melting since spring began. Meltwater and rainwater have been percolating down through snow on tops of glaciers.

But the runoff from glaciers isn’t as great now as it’ll be in another month, even though sunlight is striking the northern hemisphere most directly around now.

So wait another month for the hottest weather. It’ll come when the days are already beginning to shorten again, as Earth continues to move in orbit around the sun, bringing us closer to another winter.

And so the cycle continues.

Hello summer solstice!

Bottom line: The 2018 June happens on June 21 at 10:07 UTC. That’s 5:07 a.m. CDT in North America. This solstice – which marks the beginning of summer in the Northern Hemisphere – marks the sun’s most northerly point in Earth’s sky. It’s an event celebrated by people throughout the ages.

Visit EarthSky Tonight for easy-to-use night sky charts and info. Updated daily.

Celebrate the summer solstice as the Chinese philosophers did

Why the hottest weather isn’t on the longest day

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/1fl9JNp