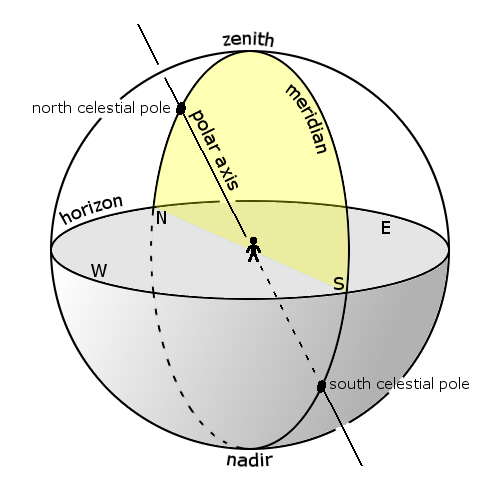

Tonight, if you have a dark sky, you’ll be able to pick the constellation Draco the Dragon winding around the North Star, Polaris. The image at the top of this post shows Draco as depicted in an old star atlas by Johannes Hevelius in 1690. See the circle around it? That circle indicates stars that are circumpolar, or always visible somewhere in the northern sky. As you can see, the constellation of the Dragon winds around the sky’s north celestial pole.

How can you see the Dragon? The Big Dipper can help guide you. Just remember … the entire Dragon requires a dark sky to be seen. You’ll find the Big Dipper high in the north on June evenings. The two outer stars in the Dipper’s bowl point to Polaris, the North Star, which marks the end of the Little Dipper’s handle.

The Dragon winds between the Big and Little Dippers, as shown on the chart below:

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

The Little Dipper is relatively faint. If you can find both Dippers, then your sky is probably pretty dark. And you’ll need that dark sky to see Draco. You’ll have to let your eyes and imagination drift a bit to see the entire winding shape of the Dragon in the northern heavens.

Also – if you can find both Dippers, and if your sky is relatively dark – you can easily pick out another noteworthy star in Draco. This star is Thuban, easy to find by looking between the Dippers. Thuban is famous for having served as a pole star around 3000 B.C. This date coincides with the beginning of the building of the pyramids in Egypt. It’s said that the descending passage of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Gizeh was built to point directly at Thuban. So our ancestors knew and celebrated this star.

Read more about Thuban, a former pole star

There are two more prominent stars to look for in the Dragon. These stars are Eltanin and Rastaban, and they lie in the head of Draco. They represent the Dragon’s Eyes.

For years, I’ve glanced randomly up in the north at this time of year and noticed these two stars, Eltanin and Rastaban, in Draco. They’re noticeable because they’re relatively bright and near each other. There’s always that split-second when I ask myself with some excitement what two stars are those? It’s then that my eyes drift to blue-white Vega nearby . . . and I know, by Vega’s nearness, that they are the Dragon’s Eyes. Notice the relationship between Vega and the Dragon’s Eyes on the chart below:

Eltanin and Rastaban are fun to pick out, and, what’s more, they nearly mark the radiant point for the annual October Draconid meteor shower. Double bonus!

From tropical and subtropical latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, the stars Rastaban and Eltanin shine quite low in the northern sky (below Vega). In either hemisphere, at all time zones, the Dragon’s eyes climb highest up in the sky around midnight (1 a.m. daylight time) in mid-June, 11 p.m. (midnight daylight time) in early July, and 9 p.m. (10 p.m. daylight time) in early August.

From temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere (southern Australia and New Zealand), the Dragon’s eyes never climb above your horizon (but you can catch the star Vega way low in your northern sky).

Meanwhile, people at mid-northern latitudes get to view the Dragon’s eyes all night long! Circumpolar … remember?

Read more about Eltanin and Rastaban

Draco and its stars Rastaban and Eltanin, as captured from Indonesia by Martin Marthadinata in May 2017.

Bottom line: Let your eyes and imagination drift a bit to see the entire winding shape of Draco the Dragon in the northern sky. If you do spot it, be sure to pick out Thuban, a former pole star, and the Dragon’s Eyes!

Read more: How to find the Big Dipper

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/1RXaMB9

Tonight, if you have a dark sky, you’ll be able to pick the constellation Draco the Dragon winding around the North Star, Polaris. The image at the top of this post shows Draco as depicted in an old star atlas by Johannes Hevelius in 1690. See the circle around it? That circle indicates stars that are circumpolar, or always visible somewhere in the northern sky. As you can see, the constellation of the Dragon winds around the sky’s north celestial pole.

How can you see the Dragon? The Big Dipper can help guide you. Just remember … the entire Dragon requires a dark sky to be seen. You’ll find the Big Dipper high in the north on June evenings. The two outer stars in the Dipper’s bowl point to Polaris, the North Star, which marks the end of the Little Dipper’s handle.

The Dragon winds between the Big and Little Dippers, as shown on the chart below:

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

The Little Dipper is relatively faint. If you can find both Dippers, then your sky is probably pretty dark. And you’ll need that dark sky to see Draco. You’ll have to let your eyes and imagination drift a bit to see the entire winding shape of the Dragon in the northern heavens.

Also – if you can find both Dippers, and if your sky is relatively dark – you can easily pick out another noteworthy star in Draco. This star is Thuban, easy to find by looking between the Dippers. Thuban is famous for having served as a pole star around 3000 B.C. This date coincides with the beginning of the building of the pyramids in Egypt. It’s said that the descending passage of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Gizeh was built to point directly at Thuban. So our ancestors knew and celebrated this star.

Read more about Thuban, a former pole star

There are two more prominent stars to look for in the Dragon. These stars are Eltanin and Rastaban, and they lie in the head of Draco. They represent the Dragon’s Eyes.

For years, I’ve glanced randomly up in the north at this time of year and noticed these two stars, Eltanin and Rastaban, in Draco. They’re noticeable because they’re relatively bright and near each other. There’s always that split-second when I ask myself with some excitement what two stars are those? It’s then that my eyes drift to blue-white Vega nearby . . . and I know, by Vega’s nearness, that they are the Dragon’s Eyes. Notice the relationship between Vega and the Dragon’s Eyes on the chart below:

Eltanin and Rastaban are fun to pick out, and, what’s more, they nearly mark the radiant point for the annual October Draconid meteor shower. Double bonus!

From tropical and subtropical latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, the stars Rastaban and Eltanin shine quite low in the northern sky (below Vega). In either hemisphere, at all time zones, the Dragon’s eyes climb highest up in the sky around midnight (1 a.m. daylight time) in mid-June, 11 p.m. (midnight daylight time) in early July, and 9 p.m. (10 p.m. daylight time) in early August.

From temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere (southern Australia and New Zealand), the Dragon’s eyes never climb above your horizon (but you can catch the star Vega way low in your northern sky).

Meanwhile, people at mid-northern latitudes get to view the Dragon’s eyes all night long! Circumpolar … remember?

Read more about Eltanin and Rastaban

Draco and its stars Rastaban and Eltanin, as captured from Indonesia by Martin Marthadinata in May 2017.

Bottom line: Let your eyes and imagination drift a bit to see the entire winding shape of Draco the Dragon in the northern sky. If you do spot it, be sure to pick out Thuban, a former pole star, and the Dragon’s Eyes!

Read more: How to find the Big Dipper

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/1RXaMB9