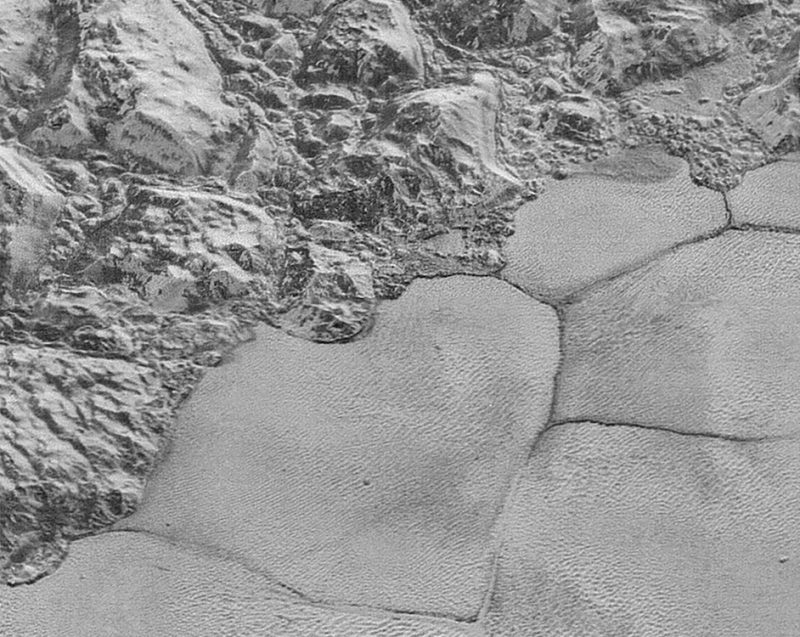

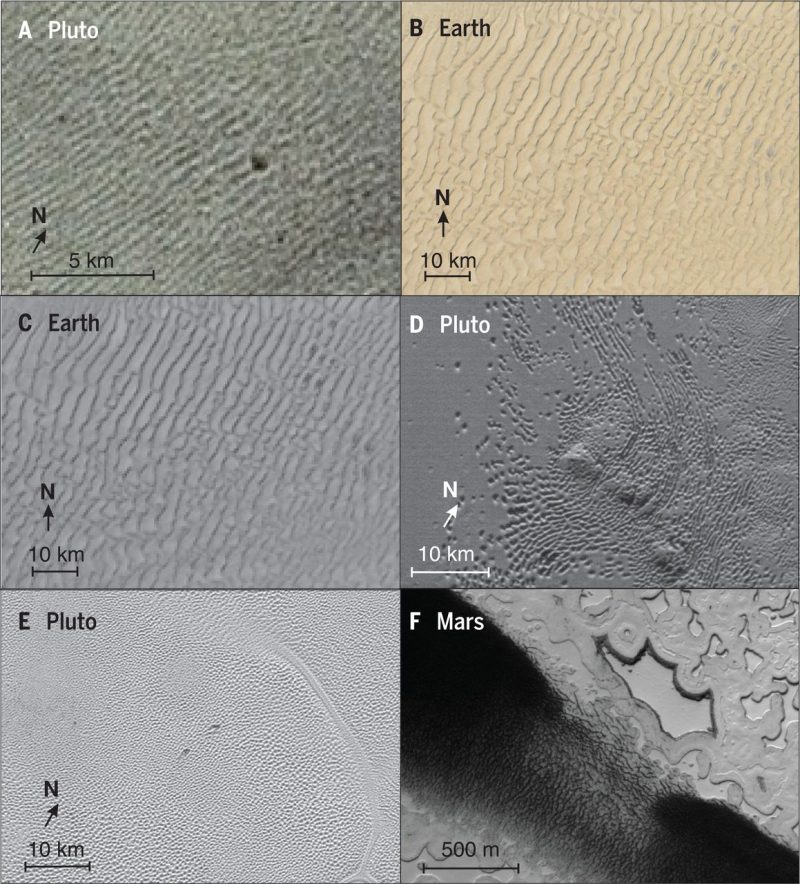

Image from New Horizons showing part of the edge of the Sputnik Planitia region. Methane dunes can be seen covering the smooth icy plains adjacent to the mountains. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

We all know how common sand dunes are on Earth – just go to practically any desert region to see them in their various shapes and sizes. Thanks to robotic space explorers, we also know they exist elsewhere in the solar system, including Mars, Venus, Titan and even a comet. And now, as reported on June 1, 2018, there is one more place to add to the list – Pluto!

This cold, almost airless little world might seem like the last place to find dunes, but the New Horizons probe found them, according to new research that has been done with the images and data sent back in 2015.

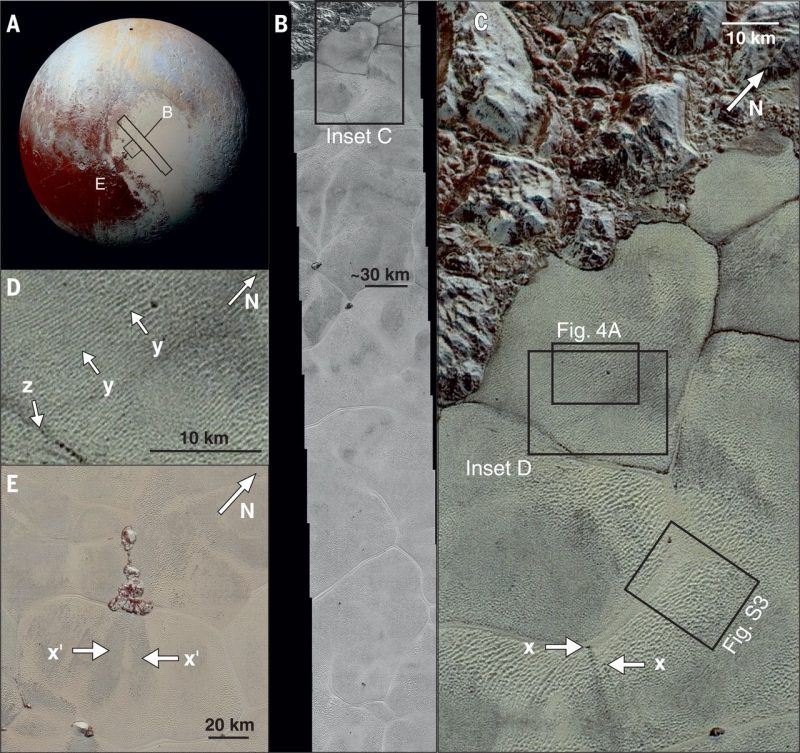

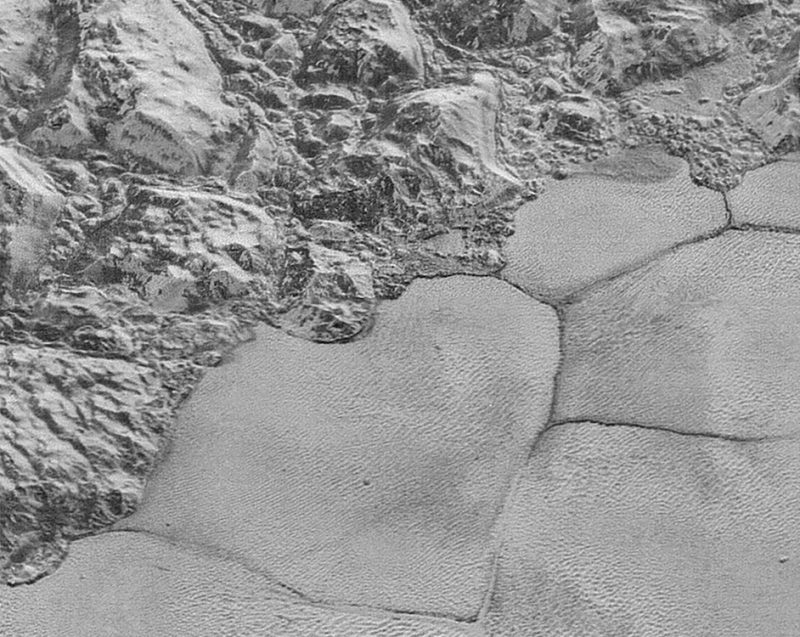

A collection of New Horizons imagery showing locations of dunes in Sputnik Planitia on Pluto. Image via Science.

From the new paper:

Wind-blown sand or ice dunes are known on Earth, Mars, Venus, Titan, and comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Telfer et al. used images taken by the New Horizons spacecraft to identify dunes in the Sputnik Planitia region on Pluto (see the Perspective by Hayes). Modeling shows that these dunes could be formed by sand-sized grains of solid methane ice transported in typical Pluto winds. The methane grains could have been lofted into the atmosphere by the melting of surrounding nitrogen ice or blown down from nearby mountains. Understanding how dunes form under Pluto conditions will help with interpreting similar features found elsewhere in the solar system.

As noted by Matt Telfer, a lecturer in physical geography at the University of Plymouth in England, in Space.com:

Pluto’s atmosphere and surface are interacting in a way that geologically/geomorphologically alters the surface. That’s exciting not just because it shows (again) the dynamism of these small, cold, dark distant worlds, but also for its inferences for very early solar system bodies.

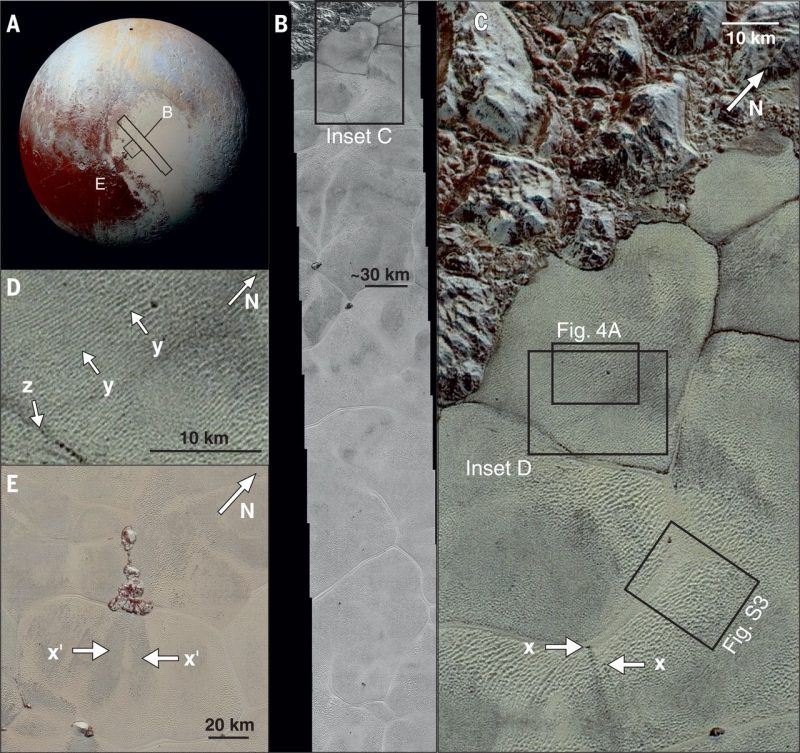

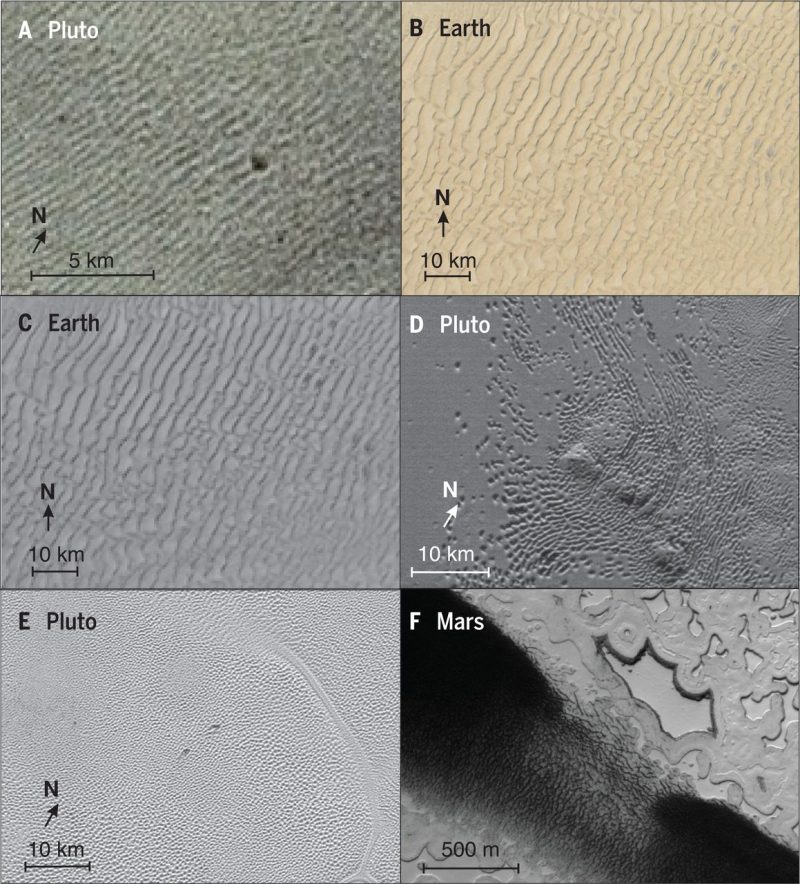

Comparison of dunes and sublimation features on Pluto, Earth and Mars. Image via NASA/JPL/University of Arizona (ESP_014342_0930_RED).

The dunes, first noticed as unusual ridges, were spotted along the western edge of Sputnik Planitia, a vast smooth plain of nitrogen ice, adjacent to the Al-Idrisi Montes mountain range (and in another uniquely Plutonian twist, the mountains on Pluto are composed of solid water ice, not rock). Upon closer inspection, they looked a lot like dunes, but were they? Another idea was that they could be sublimation pits, where sunlight causes icy material to sublime, and many had been seen elsewhere on Sputnik Planitia. According to Telfer:

We’re sure. It’s actually the relatively simple stuff, like their location, alignment (undisturbed by glacial movement, unlike the sublimation pits elsewhere), orientation (including the adjacent orthogonal wind streaks), and changes in regional orientation and spacing that nail it. It all makes perfect sense for dunes, and doesn’t match what we’d see for sublimation pits.

Thanks to New Horizons, we saw Pluto up close for the first time in history. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

On Pluto, however, the dunes are thought to be formed by grains of methane ice which originated in the mountains (where methane “snow” has also been seen), although nitrogen ice grains are another possibility. But the question is, how do they form? Pluto’s atmosphere, as it is, is extremely tenuous. As explained by Alexander Hayes, an assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell University:

What makes this discovery surprising is that the sediment can be mobilized despite Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere, with a surface pressure (1 Pa) that is a factor of 100,000 times lower than that on Earth.

According to the researchers, the dunes are most likely composed of methane ice particles, or possible nitrogen ice particles, not sand like on Earth. Their appearance, however, is very similar to dunes seen on Earth and elsewhere.

Stunning view of Pluto just after closest approach by New Horizons, with the hazy bluish atmosphere backlit by the sun. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

This discovery is an indication of another way in which Pluto mimics Earth, but in a way that is utterly unique and alien. Pluto has mountains, but they are made of rock-hard water ice, with methane snow on top. The icy plains are nitrogen ice, not water. The atmosphere is blue, but extremely thin compared to the atmosphere on Earth, or even Mars. There also also towering ice “spikes” resembling penitentes on Earth, but much larger. There is even evidence for a water ocean, but deep underground, similar to moons like Europa, Enceladus and Titan.

On Jan. 1, 2019, New Horizons will fly past another Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) called Ultima Thule (aka 2014 MU69). This will be the most distant object to ever be visited by a spacecraft in our solar system so far.

Bottom line: Expect the unexpected. That would seem to be a good rule of thumb to follow in planetary exploration. The dunes on Pluto are another good example of how incredible discoveries are being made by many spacecraft exploring our solar system. Coming across something which presumably shouldn’t be there, but is, is one of the most exciting things about space exploration. You just never know what you might find.

Source: Dunes on Pluto

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2JlHNs0

Image from New Horizons showing part of the edge of the Sputnik Planitia region. Methane dunes can be seen covering the smooth icy plains adjacent to the mountains. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

We all know how common sand dunes are on Earth – just go to practically any desert region to see them in their various shapes and sizes. Thanks to robotic space explorers, we also know they exist elsewhere in the solar system, including Mars, Venus, Titan and even a comet. And now, as reported on June 1, 2018, there is one more place to add to the list – Pluto!

This cold, almost airless little world might seem like the last place to find dunes, but the New Horizons probe found them, according to new research that has been done with the images and data sent back in 2015.

A collection of New Horizons imagery showing locations of dunes in Sputnik Planitia on Pluto. Image via Science.

From the new paper:

Wind-blown sand or ice dunes are known on Earth, Mars, Venus, Titan, and comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Telfer et al. used images taken by the New Horizons spacecraft to identify dunes in the Sputnik Planitia region on Pluto (see the Perspective by Hayes). Modeling shows that these dunes could be formed by sand-sized grains of solid methane ice transported in typical Pluto winds. The methane grains could have been lofted into the atmosphere by the melting of surrounding nitrogen ice or blown down from nearby mountains. Understanding how dunes form under Pluto conditions will help with interpreting similar features found elsewhere in the solar system.

As noted by Matt Telfer, a lecturer in physical geography at the University of Plymouth in England, in Space.com:

Pluto’s atmosphere and surface are interacting in a way that geologically/geomorphologically alters the surface. That’s exciting not just because it shows (again) the dynamism of these small, cold, dark distant worlds, but also for its inferences for very early solar system bodies.

Comparison of dunes and sublimation features on Pluto, Earth and Mars. Image via NASA/JPL/University of Arizona (ESP_014342_0930_RED).

The dunes, first noticed as unusual ridges, were spotted along the western edge of Sputnik Planitia, a vast smooth plain of nitrogen ice, adjacent to the Al-Idrisi Montes mountain range (and in another uniquely Plutonian twist, the mountains on Pluto are composed of solid water ice, not rock). Upon closer inspection, they looked a lot like dunes, but were they? Another idea was that they could be sublimation pits, where sunlight causes icy material to sublime, and many had been seen elsewhere on Sputnik Planitia. According to Telfer:

We’re sure. It’s actually the relatively simple stuff, like their location, alignment (undisturbed by glacial movement, unlike the sublimation pits elsewhere), orientation (including the adjacent orthogonal wind streaks), and changes in regional orientation and spacing that nail it. It all makes perfect sense for dunes, and doesn’t match what we’d see for sublimation pits.

Thanks to New Horizons, we saw Pluto up close for the first time in history. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

On Pluto, however, the dunes are thought to be formed by grains of methane ice which originated in the mountains (where methane “snow” has also been seen), although nitrogen ice grains are another possibility. But the question is, how do they form? Pluto’s atmosphere, as it is, is extremely tenuous. As explained by Alexander Hayes, an assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell University:

What makes this discovery surprising is that the sediment can be mobilized despite Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere, with a surface pressure (1 Pa) that is a factor of 100,000 times lower than that on Earth.

According to the researchers, the dunes are most likely composed of methane ice particles, or possible nitrogen ice particles, not sand like on Earth. Their appearance, however, is very similar to dunes seen on Earth and elsewhere.

Stunning view of Pluto just after closest approach by New Horizons, with the hazy bluish atmosphere backlit by the sun. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

This discovery is an indication of another way in which Pluto mimics Earth, but in a way that is utterly unique and alien. Pluto has mountains, but they are made of rock-hard water ice, with methane snow on top. The icy plains are nitrogen ice, not water. The atmosphere is blue, but extremely thin compared to the atmosphere on Earth, or even Mars. There also also towering ice “spikes” resembling penitentes on Earth, but much larger. There is even evidence for a water ocean, but deep underground, similar to moons like Europa, Enceladus and Titan.

On Jan. 1, 2019, New Horizons will fly past another Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) called Ultima Thule (aka 2014 MU69). This will be the most distant object to ever be visited by a spacecraft in our solar system so far.

Bottom line: Expect the unexpected. That would seem to be a good rule of thumb to follow in planetary exploration. The dunes on Pluto are another good example of how incredible discoveries are being made by many spacecraft exploring our solar system. Coming across something which presumably shouldn’t be there, but is, is one of the most exciting things about space exploration. You just never know what you might find.

Source: Dunes on Pluto

Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2JlHNs0