To celebrate the discovery of new species of animals, plants and microbes, the International Institute for Species Exploration (IISE) compiles an annual top 10 new species list from the approximately 18,000 new species named the previous year.

The first list was compiled in 2008. The list is released each year around May 23 to honor of the birthday of Carl Linnaeus, the 18th century Swedish botanist who is considered the father of modern taxonomy – our modern binomial classification system for naming organisms.

Here are the top 10 for 2018:

(In alphabetical order by scientific name)

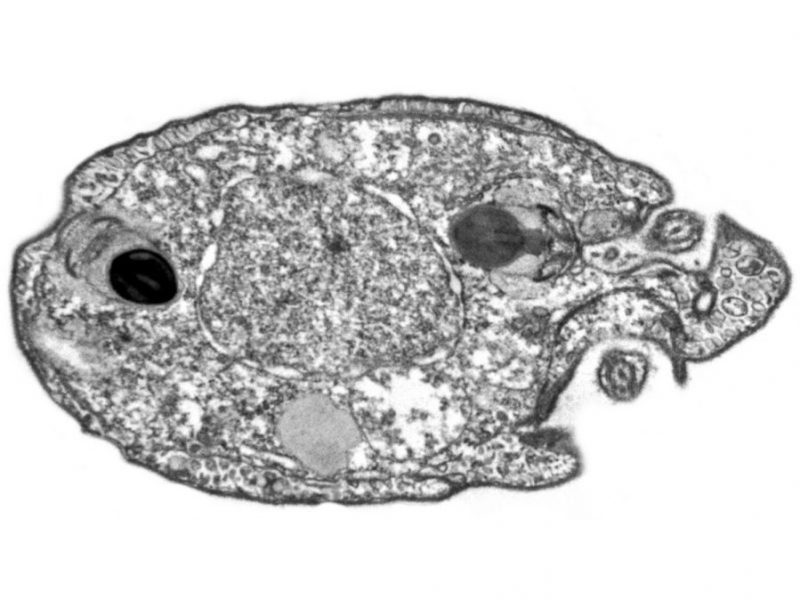

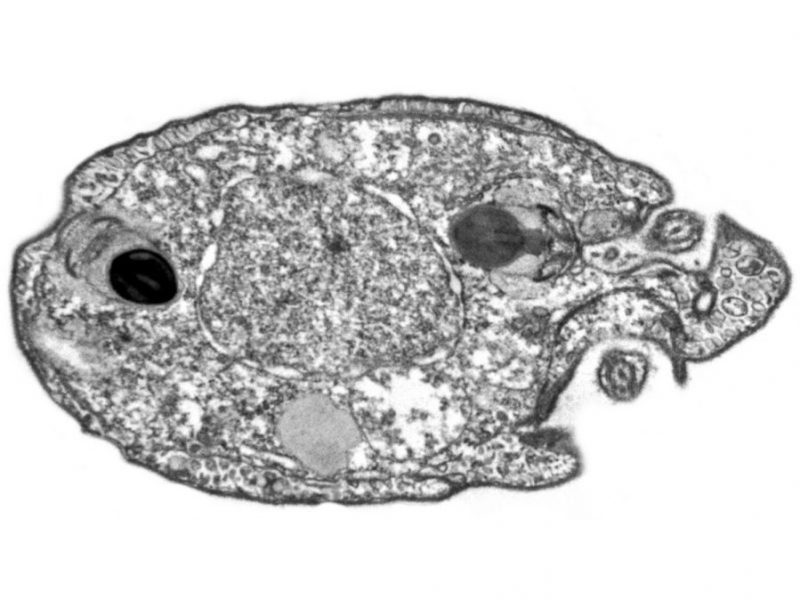

Protist (Ancoracysta twista) Location: Unknown

Discovered in an aquarium in San Diego, California, this new single-celled protist has challenged scientists to determine its nearest relatives. It does not fit neatly within any known group and appears to be a previously undiscovered early lineage of Eukaryota with a uniquely rich mitochondrial genome. Eukaryotes are organisms with cells in which genetic material is organized in a membrane-bound nucleus. The geographic origin of the species in the wild is not known. It was found in a tropical aquarium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography on a brain coral. Image via IISE.

Atlantic Forest Tree (Dinizia jueirana-facao) Location: Brazil

Dinizia jueirana-facao, up to 130 feet (40 m) in height, emerges above the canopy of the semi-deciduous, riparian, pristine Atlantic forest in Brazil where it is found. This massive tree, weighs an estimated 62 tons (56,000 kg). While large in dimension, the tree is limited in numbers – it is known from only 25 individuals, about half of which are in the protected area, making it critically endangered. Image via IISE.

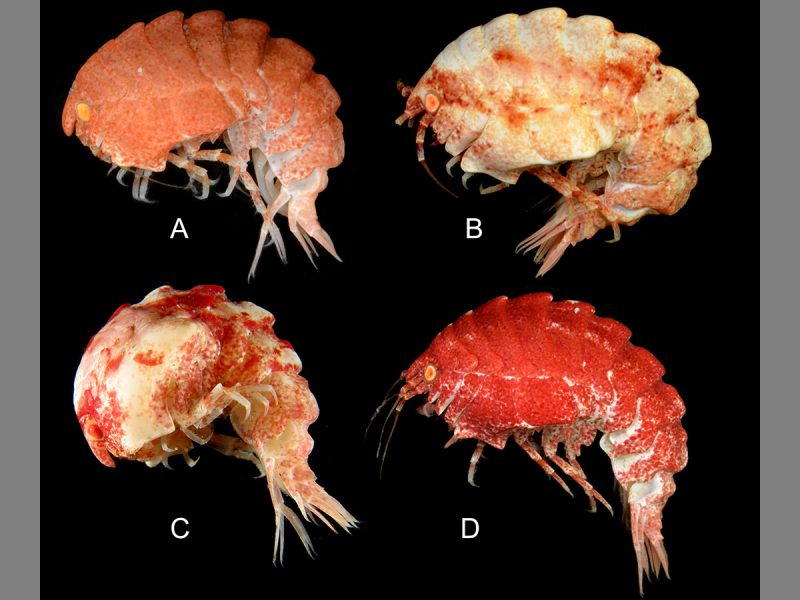

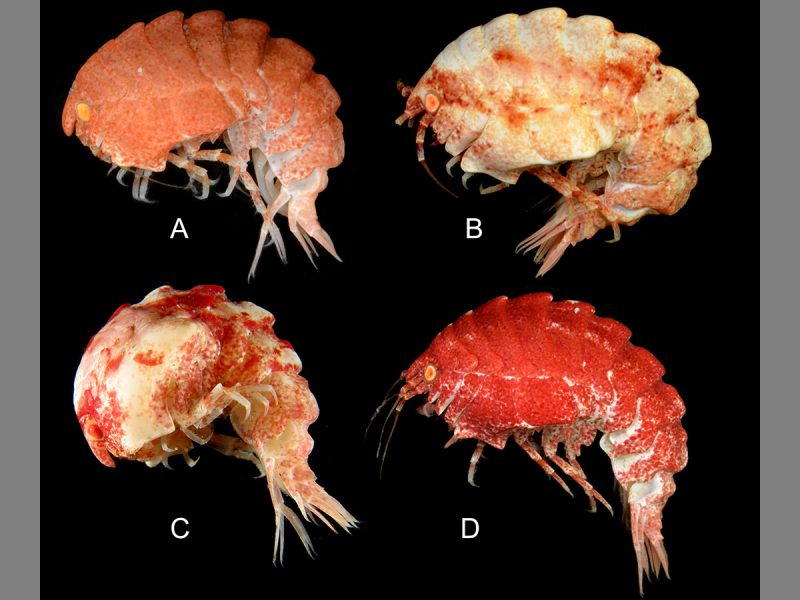

Amphipod (Epimeria quasimodo) Location: Antarctic Ocean

Here’s a new species whose name might ring a bell. This amphipod, about 2 inches (50mm) in length, Epimeria quasimodo, is named for Victor Hugo’s character, Quasimodo the hunchback, in reference to its somewhat humped back. It is one of 26 new species of amphipods of the genus Epimeria from the Southern Ocean with incredible spines and vivid colors. Image via IISE.

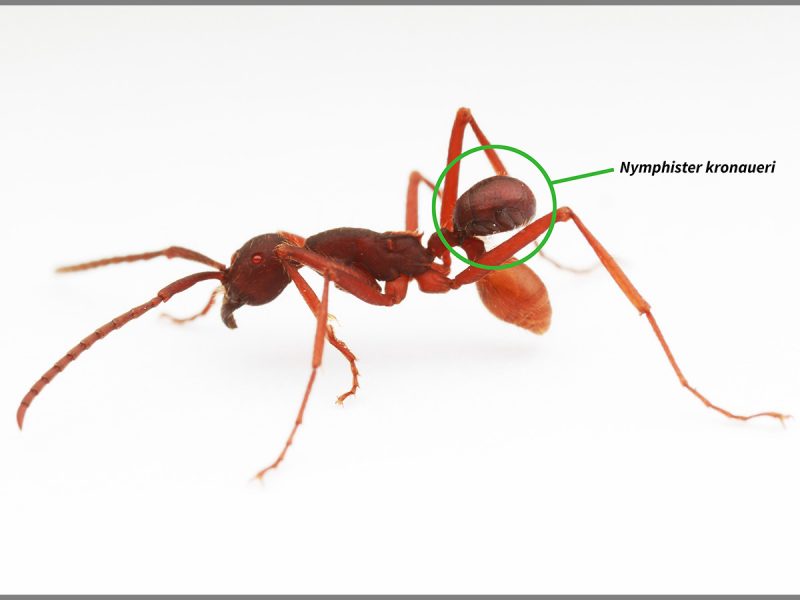

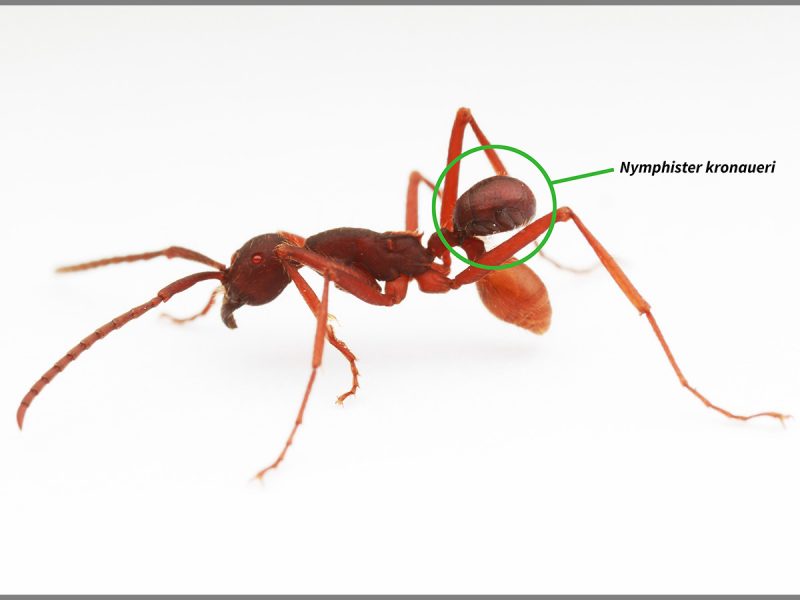

Baffling Beetle: (Nymphister kronaueri). Location: Costa Rica

This tiny beetle that lives among ants. At about 1.5 mm in length, 16 of them could line up head-to-tail in the space of an inch (2.5 cm). But their story gets much better. They live exclusively among one species of army ant. The host ants, as with other army ants, do not construct permanent nests but are nomadic. The beetle’s body is the precise size, shape and color of the abdomen of a worker ant. The beetle uses its mouthparts to grab the skinny portion of the host abdomen and hang on, letting the ant do the walking. Image via IISE.

Tapanuli Orangutan: Pongo tapanuliensis Location: Sumatra, Indonesia

This is the most imperiled great ape in the world. Only an estimated 800 individuals exist in fragmented habitat spread over about 250,000 acres (about 1,000 square kilometers) on medium elevation hills and submontane forests from about 1,000 to 4,000 feet (300 to 1,300 m) above sea level, with densest populations in primary forest. Size is similar to other orangutans, with females under 4 feet (1.21 m) in height and males under 5 feet (1.53 m). Image via IISE.

Swire’s Snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei) Location: Western Pacific Ocean

In the dark abyss of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific lies the deepest spot in the world’s oceans and the deepest-dwelling fish ever discovered with verified depth. Large numbers of the new species were attracted to traps baited with mackerel. Pseudoliparis swirei is a small, tadpole-like fish measuring a little over four inches in length (112 mm) yet appears to be the top predator in its benthic community at the bottom of this particularly deep sea. Image via IISE.

Heterotrophic Flower (Sciaphila sugimotoi) Location: Ishigaki Island, Japan

Most plants are autotrophic, capturing solar energy to feed themselves by means of photosynthesis. A few, like the newly discovered Sciaphila sugimotoi, are heterotrophic, deriving their sustenance from other organisms. In this case, the plant is symbiotic with a fungus from which it derives nutrition without harm to the partner. Image via IISE.

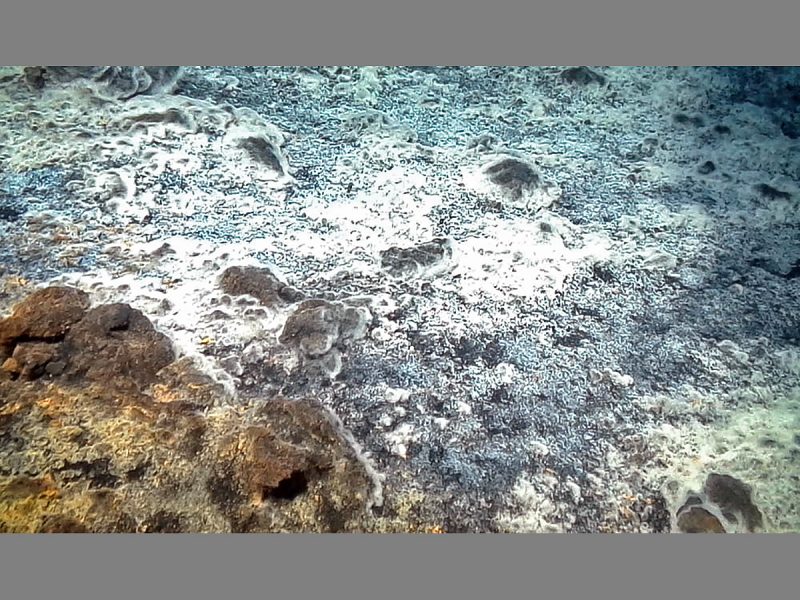

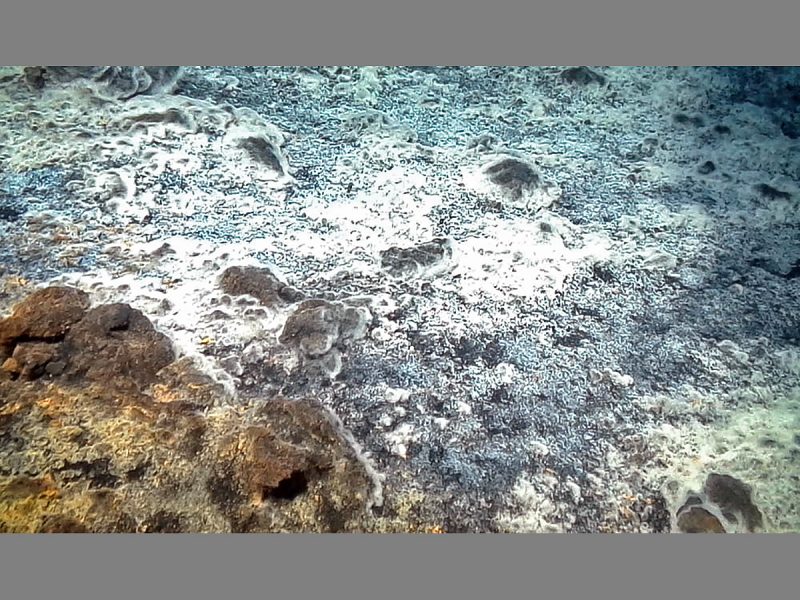

Volcanic Bacterium (Thiolava veneris) Location: Canary Islands

When the submarine volcano Tagoro erupted off the coast of El Hierro in the Canary Islands in 2011, it abruptly increased water temperature, decreased oxygen and released massive quantities of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, wiping out much of the existing marine ecosystem. Three years later, scientists found the first colonizers of this newly deposited area – a new species of proteobacteria producing long, hair-like structures composed of bacterial cells within a sheath. The bacteria formed a massive white mat, extending for nearly half an acre (about 2,000 square meters) around the summit of the newly formed Tagoro volcanic cone at depths of about 430 feet (129-132 m). Image via IISE.

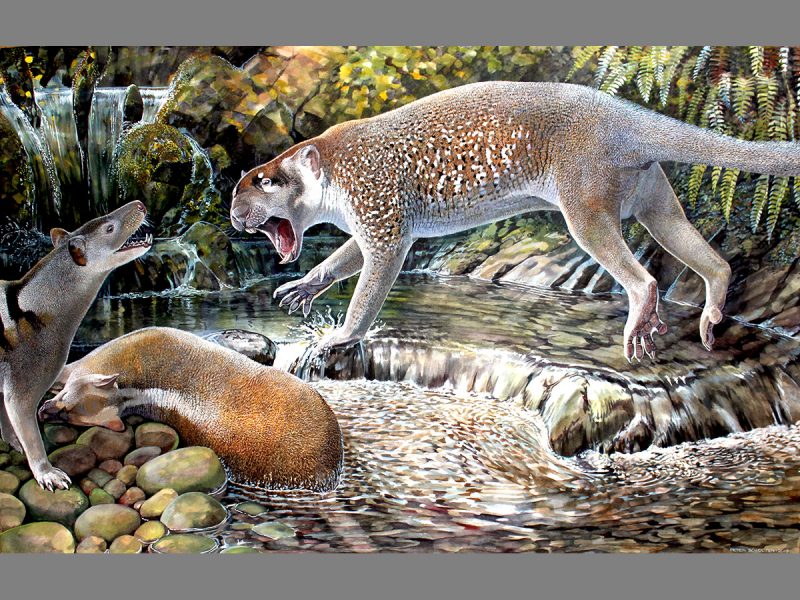

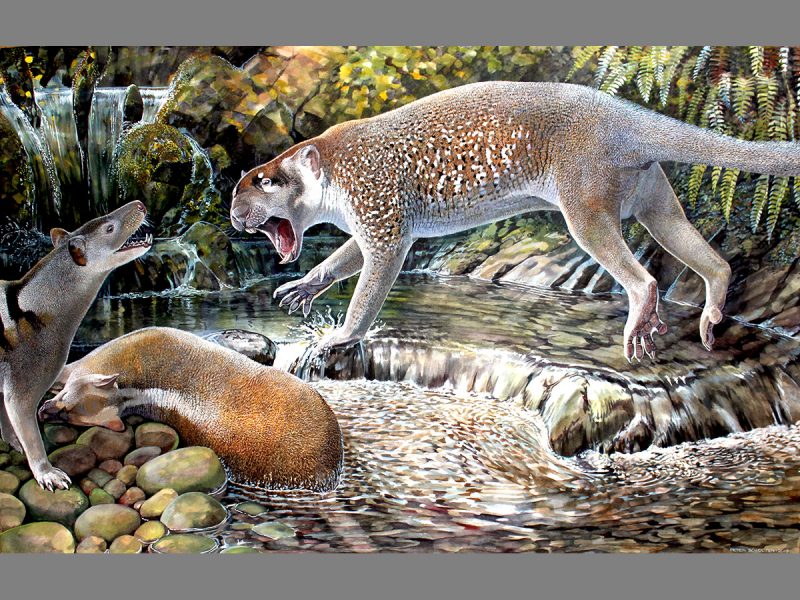

Marsupial Lion (Wakaleo schouteni) Location: Australia

In the late Oligocene, which ended about 23 million years ago as the Miocene arrived, a marsupial lion, Wakaleo schouteni, roamed Australia’s open forest habitat in northwestern Queensland, stalking its prey. Scientists recovered fossils in Queensland that proved to be a previously unknown fossil marsupial lion. Weighing in at about 50 pounds, more or less the size of a Siberian husky dog, this predator spent part of its time in trees. Its teeth suggest that it was not completely reliant on meat but was, rather, an omnivore. Image via IISE.

Cave Beetle (Xuedytes bellus) Location: China

Beetles that become adapted to life in the permanent darkness of caves often resemble one another in a whole suite of characteristics including a compact body, greatly elongated, spider-like appendages, and loss of flight wings, eyes and pigmentation. Xuedytes bellus was discovered in a cave in Du’an, Guangxi Province, China. Image via IISE.

Bottom line: List of top 10 new species 2018.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ssN0Yb

To celebrate the discovery of new species of animals, plants and microbes, the International Institute for Species Exploration (IISE) compiles an annual top 10 new species list from the approximately 18,000 new species named the previous year.

The first list was compiled in 2008. The list is released each year around May 23 to honor of the birthday of Carl Linnaeus, the 18th century Swedish botanist who is considered the father of modern taxonomy – our modern binomial classification system for naming organisms.

Here are the top 10 for 2018:

(In alphabetical order by scientific name)

Protist (Ancoracysta twista) Location: Unknown

Discovered in an aquarium in San Diego, California, this new single-celled protist has challenged scientists to determine its nearest relatives. It does not fit neatly within any known group and appears to be a previously undiscovered early lineage of Eukaryota with a uniquely rich mitochondrial genome. Eukaryotes are organisms with cells in which genetic material is organized in a membrane-bound nucleus. The geographic origin of the species in the wild is not known. It was found in a tropical aquarium at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography on a brain coral. Image via IISE.

Atlantic Forest Tree (Dinizia jueirana-facao) Location: Brazil

Dinizia jueirana-facao, up to 130 feet (40 m) in height, emerges above the canopy of the semi-deciduous, riparian, pristine Atlantic forest in Brazil where it is found. This massive tree, weighs an estimated 62 tons (56,000 kg). While large in dimension, the tree is limited in numbers – it is known from only 25 individuals, about half of which are in the protected area, making it critically endangered. Image via IISE.

Amphipod (Epimeria quasimodo) Location: Antarctic Ocean

Here’s a new species whose name might ring a bell. This amphipod, about 2 inches (50mm) in length, Epimeria quasimodo, is named for Victor Hugo’s character, Quasimodo the hunchback, in reference to its somewhat humped back. It is one of 26 new species of amphipods of the genus Epimeria from the Southern Ocean with incredible spines and vivid colors. Image via IISE.

Baffling Beetle: (Nymphister kronaueri). Location: Costa Rica

This tiny beetle that lives among ants. At about 1.5 mm in length, 16 of them could line up head-to-tail in the space of an inch (2.5 cm). But their story gets much better. They live exclusively among one species of army ant. The host ants, as with other army ants, do not construct permanent nests but are nomadic. The beetle’s body is the precise size, shape and color of the abdomen of a worker ant. The beetle uses its mouthparts to grab the skinny portion of the host abdomen and hang on, letting the ant do the walking. Image via IISE.

Tapanuli Orangutan: Pongo tapanuliensis Location: Sumatra, Indonesia

This is the most imperiled great ape in the world. Only an estimated 800 individuals exist in fragmented habitat spread over about 250,000 acres (about 1,000 square kilometers) on medium elevation hills and submontane forests from about 1,000 to 4,000 feet (300 to 1,300 m) above sea level, with densest populations in primary forest. Size is similar to other orangutans, with females under 4 feet (1.21 m) in height and males under 5 feet (1.53 m). Image via IISE.

Swire’s Snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei) Location: Western Pacific Ocean

In the dark abyss of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific lies the deepest spot in the world’s oceans and the deepest-dwelling fish ever discovered with verified depth. Large numbers of the new species were attracted to traps baited with mackerel. Pseudoliparis swirei is a small, tadpole-like fish measuring a little over four inches in length (112 mm) yet appears to be the top predator in its benthic community at the bottom of this particularly deep sea. Image via IISE.

Heterotrophic Flower (Sciaphila sugimotoi) Location: Ishigaki Island, Japan

Most plants are autotrophic, capturing solar energy to feed themselves by means of photosynthesis. A few, like the newly discovered Sciaphila sugimotoi, are heterotrophic, deriving their sustenance from other organisms. In this case, the plant is symbiotic with a fungus from which it derives nutrition without harm to the partner. Image via IISE.

Volcanic Bacterium (Thiolava veneris) Location: Canary Islands

When the submarine volcano Tagoro erupted off the coast of El Hierro in the Canary Islands in 2011, it abruptly increased water temperature, decreased oxygen and released massive quantities of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, wiping out much of the existing marine ecosystem. Three years later, scientists found the first colonizers of this newly deposited area – a new species of proteobacteria producing long, hair-like structures composed of bacterial cells within a sheath. The bacteria formed a massive white mat, extending for nearly half an acre (about 2,000 square meters) around the summit of the newly formed Tagoro volcanic cone at depths of about 430 feet (129-132 m). Image via IISE.

Marsupial Lion (Wakaleo schouteni) Location: Australia

In the late Oligocene, which ended about 23 million years ago as the Miocene arrived, a marsupial lion, Wakaleo schouteni, roamed Australia’s open forest habitat in northwestern Queensland, stalking its prey. Scientists recovered fossils in Queensland that proved to be a previously unknown fossil marsupial lion. Weighing in at about 50 pounds, more or less the size of a Siberian husky dog, this predator spent part of its time in trees. Its teeth suggest that it was not completely reliant on meat but was, rather, an omnivore. Image via IISE.

Cave Beetle (Xuedytes bellus) Location: China

Beetles that become adapted to life in the permanent darkness of caves often resemble one another in a whole suite of characteristics including a compact body, greatly elongated, spider-like appendages, and loss of flight wings, eyes and pigmentation. Xuedytes bellus was discovered in a cave in Du’an, Guangxi Province, China. Image via IISE.

Bottom line: List of top 10 new species 2018.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ssN0Yb