Image via quotesgram.

Earth’s first snow might have fallen after large masses of land rose swiftly from the sea and set off dramatic changes on our planet 2.4 billion years ago. That’s according to a study published May 24, 2018, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

Geologist Ilya Bindeman is a professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at University of Oregon and the study lead author. He said in a statement:

What we speculate is that once large continents emerged, light would have been reflected back into space and that would have initiated runaway glaciation. Earth would have seen its first snowfall.

Previously submerged surfaces become exposed to weathering, leading to the accumulation of mudrocks and shales. In this scene, winter drainage at Fern Ridge Reservoir west of Eugene, Oregon, exposes mudrocks, providing an example of how newly risen land is exposed to weathering forces. Image via Ilya Bindeman.

The research team studied shale, Earth’s most abundant sedimentary rock. Shale rocks are formed by the weathering of crust. Bindeman said:

They tell you a lot about the exposure to air and light and precipitation. The process of forming shale captures organic products and eventually helps to generate oil. Shales provide us with a continuous record of weathering.

Using shale samples from every continent, the scientists looked at ratios of three common oxygen isotopes, or chemical signatures. They found evidence from as far back as 3.5 billion years ago showing traces of rainwater that caused weathering of land.

Bindeman and his team detected a major shift in the chemical makeup of 278 shale samples at the 2.4-billion-year mark. Their research suggests that those changes began when Earth was much hotter than today, when the newly-surfaced land rose rapidly and was exposed to weathering. Bindeman said the total landmass of the planet 2.4 billion years ago may have reached about two-thirds of what is seen today.

The emergence of so much land changed the flow of atmospheric gases and other chemical and physical processes, say the researchers, primarily between 2.4 billion and 2.2 billion years ago, he said.

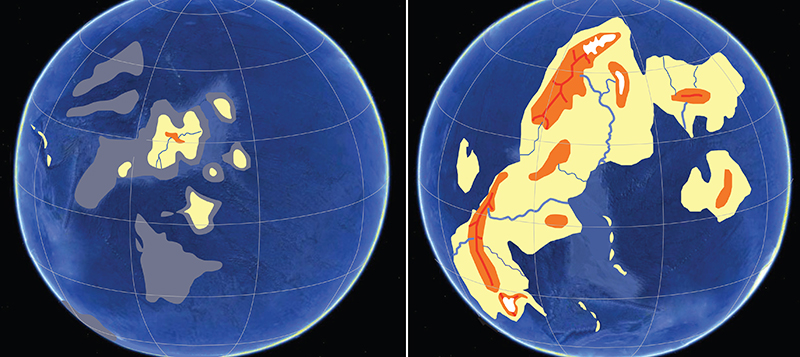

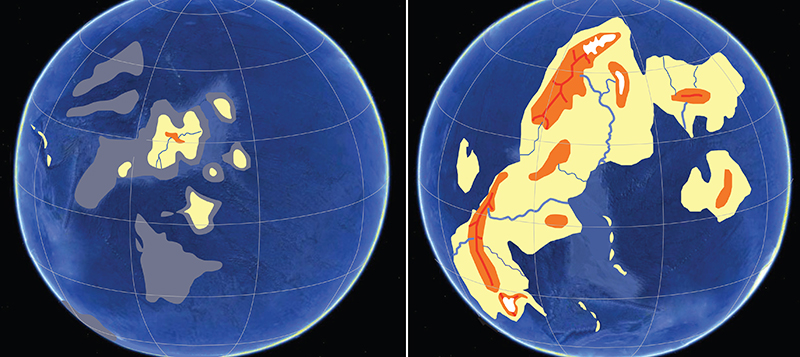

The chemical changes recorded in the rocks coincide with the theorized timing of land collisions that formed one of Earth’s first supercontinents, Kenorland, and the planet’s first high mountain ranges and plateaus. Bindeman said:

Land rising from water changes the albedo of the planet. Initially, Earth would have been dark blue with some white clouds when viewed from space. Early continents added to reflection.

Earth’s albedo is the proportion of sunlight that’s reflected by the planet’s surface.

Before and after: How Earth’s land elevations may have looked before and after the Great Oxygenation Event. Image via Ilya Bindeman.

The rapid changes, the researchers noted, may have triggered what scientists call the Great Oxygenation Event, in which atmospheric changes brought significant amounts of free oxygen into the air.

Bottom line: A new study suggests Earth got its first snowfall 2.4 billion years ago.

Read more from the University of Oregon

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2IQres8

Image via quotesgram.

Earth’s first snow might have fallen after large masses of land rose swiftly from the sea and set off dramatic changes on our planet 2.4 billion years ago. That’s according to a study published May 24, 2018, in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

Geologist Ilya Bindeman is a professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at University of Oregon and the study lead author. He said in a statement:

What we speculate is that once large continents emerged, light would have been reflected back into space and that would have initiated runaway glaciation. Earth would have seen its first snowfall.

Previously submerged surfaces become exposed to weathering, leading to the accumulation of mudrocks and shales. In this scene, winter drainage at Fern Ridge Reservoir west of Eugene, Oregon, exposes mudrocks, providing an example of how newly risen land is exposed to weathering forces. Image via Ilya Bindeman.

The research team studied shale, Earth’s most abundant sedimentary rock. Shale rocks are formed by the weathering of crust. Bindeman said:

They tell you a lot about the exposure to air and light and precipitation. The process of forming shale captures organic products and eventually helps to generate oil. Shales provide us with a continuous record of weathering.

Using shale samples from every continent, the scientists looked at ratios of three common oxygen isotopes, or chemical signatures. They found evidence from as far back as 3.5 billion years ago showing traces of rainwater that caused weathering of land.

Bindeman and his team detected a major shift in the chemical makeup of 278 shale samples at the 2.4-billion-year mark. Their research suggests that those changes began when Earth was much hotter than today, when the newly-surfaced land rose rapidly and was exposed to weathering. Bindeman said the total landmass of the planet 2.4 billion years ago may have reached about two-thirds of what is seen today.

The emergence of so much land changed the flow of atmospheric gases and other chemical and physical processes, say the researchers, primarily between 2.4 billion and 2.2 billion years ago, he said.

The chemical changes recorded in the rocks coincide with the theorized timing of land collisions that formed one of Earth’s first supercontinents, Kenorland, and the planet’s first high mountain ranges and plateaus. Bindeman said:

Land rising from water changes the albedo of the planet. Initially, Earth would have been dark blue with some white clouds when viewed from space. Early continents added to reflection.

Earth’s albedo is the proportion of sunlight that’s reflected by the planet’s surface.

Before and after: How Earth’s land elevations may have looked before and after the Great Oxygenation Event. Image via Ilya Bindeman.

The rapid changes, the researchers noted, may have triggered what scientists call the Great Oxygenation Event, in which atmospheric changes brought significant amounts of free oxygen into the air.

Bottom line: A new study suggests Earth got its first snowfall 2.4 billion years ago.

Read more from the University of Oregon

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2IQres8