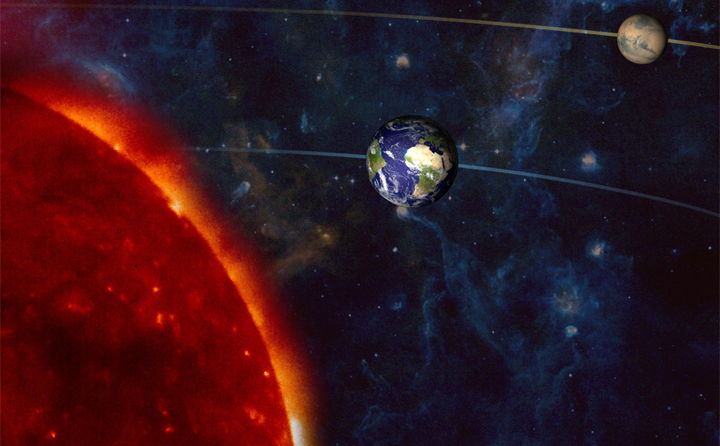

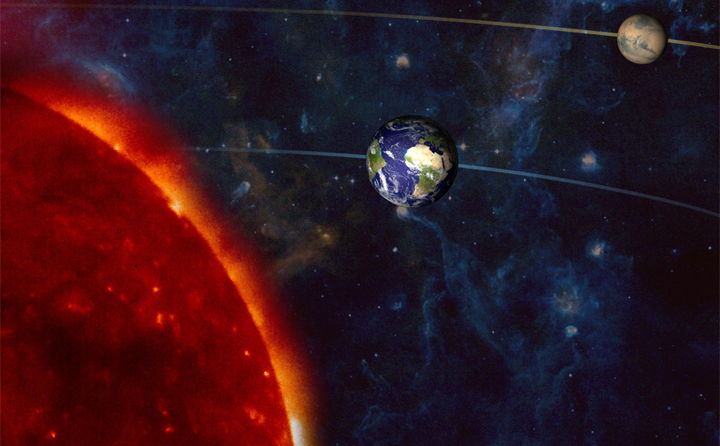

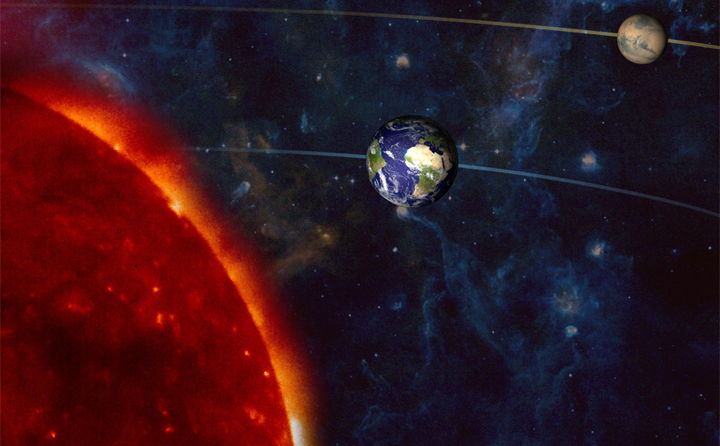

Artist’s concept of Earth (3rd planet from the sun) passing between the sun and Mars (4th planet from the sun). Not to scale. At such times, Mars appears opposite the sun in our sky, and astronomers say that Mars is in “opposition” to the sun. Mars will be in opposition next in July, 2018. Image via NASA.

Remember Mars in 2003? That was the year the red planet came closer to Earth than it had been in some 60,000 years. Mars can be faint, or it can be a bright planet. It can outshine most stars. But, in 2003, for a few months, Mars was exceedingly spectacular in our sky, outshining all the stars and planets except brilliant Venus. In 2018, Mars won’t be quite as bright as it was in 2003. But nearly!

It’ll dramatically brighten over the coming months to appear as a red dot of brilliant flame in our sky around late July, 2018.

Want to see Mars now? Check out EarthSky’s planet guide

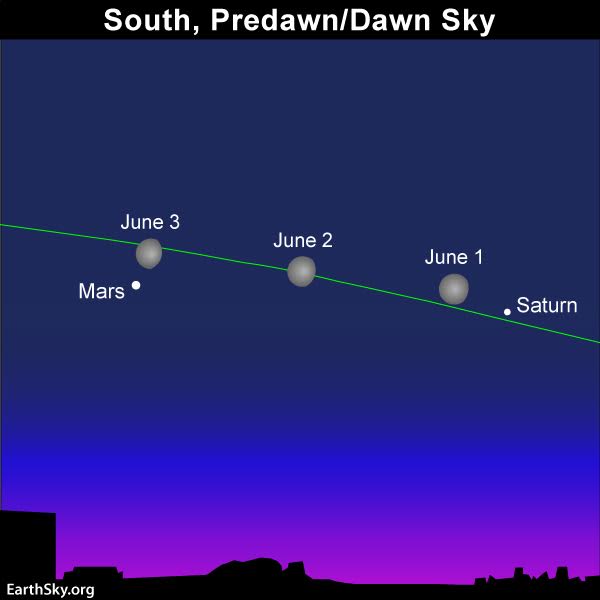

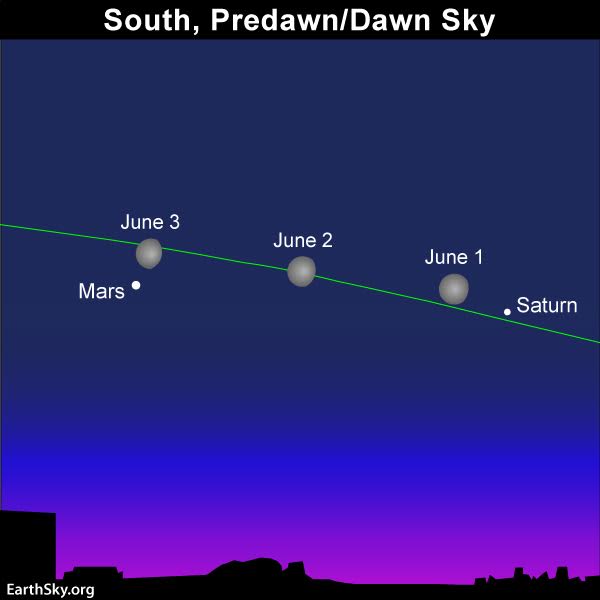

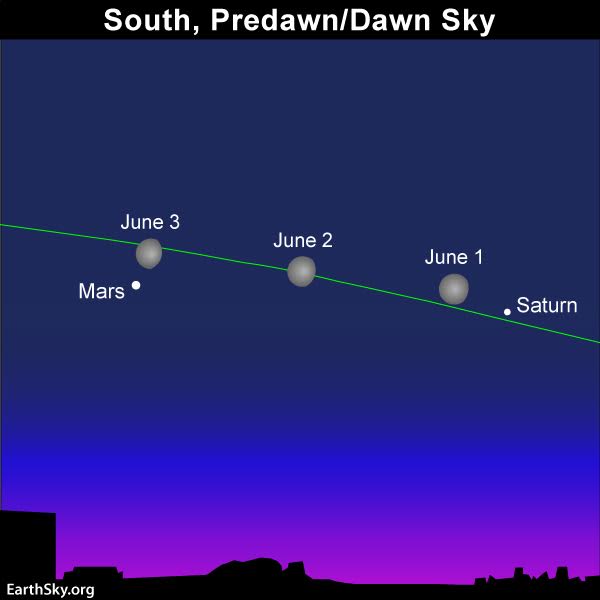

Watch for the moon to sweep past both Saturn and Mars in early June 2018.

More than any other bright planet, the appearance of Mars in our night sky changes from year to year. Its dramatic swings in brightness are part of what make Mars a fascinating planet to watch with the eye alone. Mars was faint throughout 2017. But it’s brighter now, as you might notice if you’ve been watching the planet in the predawn sky. Mars was very close to Saturn in early April (see photos), and it’s still near Saturn (though not as close) as you can see from the chart above. Jupiter is up before dawn now, too, and, when you contrast the brightness of Jupiter and Mars in April 2018, you might not believe that Mars will be brighter than Jupiter this July.

But it’s true. In late July 2018, around the time Earth sweeps between Mars and the sun, Mars will outshine Jupiter by some 1.8 times.

And that will be something to see!

See photos: A beautiful conjunction of Mars and Saturn in early April

Brighter Jupiter, fainter Mars, on January 7, 2018, via Jenney Disimon in Sabah, North Borneo. Jupiter will remain steady in brightness. Mars will brighten dramatically, to outshine Jupiter and reign as the 4th brightest object in Earth’s sky – after Venus, the moon and the sun – from about July 7 to September 7, 2018.

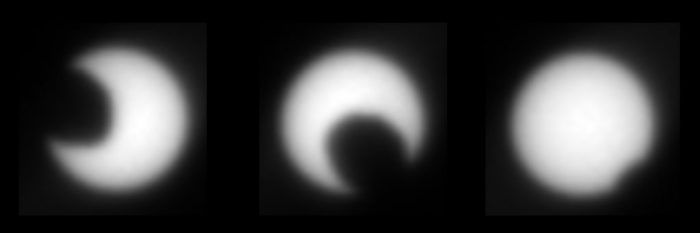

Mars isn’t very big, so its brightness – when it is bright – isn’t due to its bigness, as is true of Jupiter. Mars’ brightness, or lack of brightness, is all about how close it is to us. Image via Lunar and Planetary Institute.

So … why? Why does Mars sometimes appear very bright, and sometimes very faint?

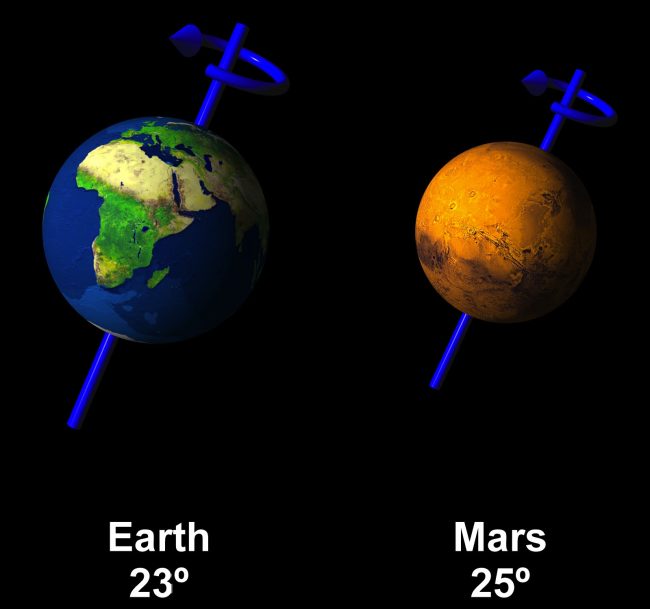

The first thing to realize is that Mars isn’t a very big world. It is only 4,219 miles (6,790 km) in diameter, making it only slightly more than half as big as Earth at 7,922 miles (12,750 km) in diameter. So, when it’s bright, its brightness isn’t due to its bigness, as is the case with Jupiter.

The main reason for Mars’ extremes in brightness has to do with the proximity (or lack of proximity) of Earth and Mars during the orbits of both worlds around the sun. It’s about the nearness in space of our two worlds. Sometimes Earth and Mars are on the same side of the solar system, and hence near one another. At other times, as it was throughout most of 2017, Mars is far across the solar system from us.

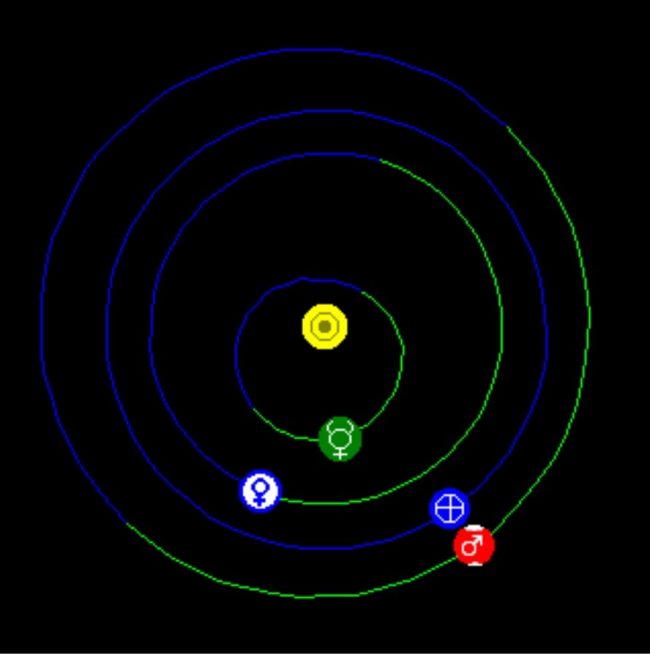

On this depiction via Fourmilab – Mars is red and Earth is blue. In early October 2017, Mars was relatively far across the solar system from Earth. The distance between our 2 worlds is relatively large, so Mars appears faint.

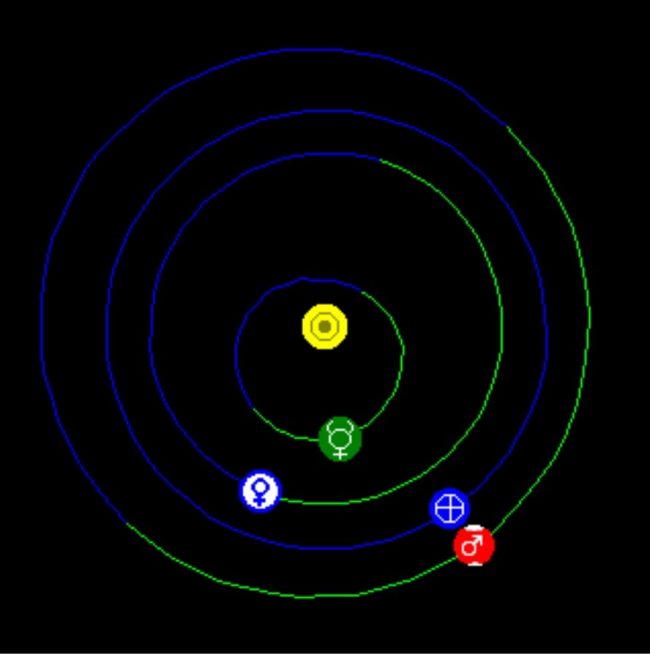

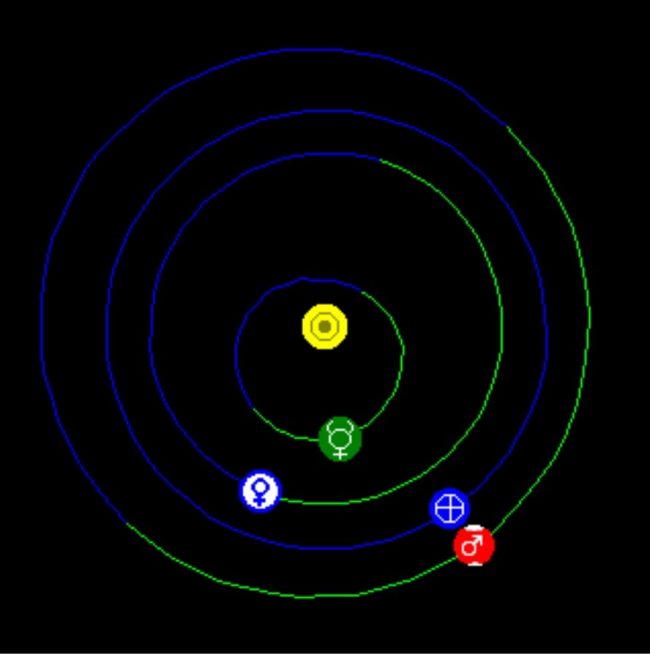

Here’s the Fourmilab depiction for April 23, 2018. Mars is red, Earth is blue. In contrast to the chart above, you can see that Earth and Mars are now closer together. Earth is catching up to Mars in the race of the planets around the sun. Thus, Mars is getting brighter!

Earth will pass between between the sun and Mars on July 27, 2018. Then, the distance between our two worlds will be at its least for this 2-year period, and Mars will appear brightest in our sky. Image via Fourmilab.

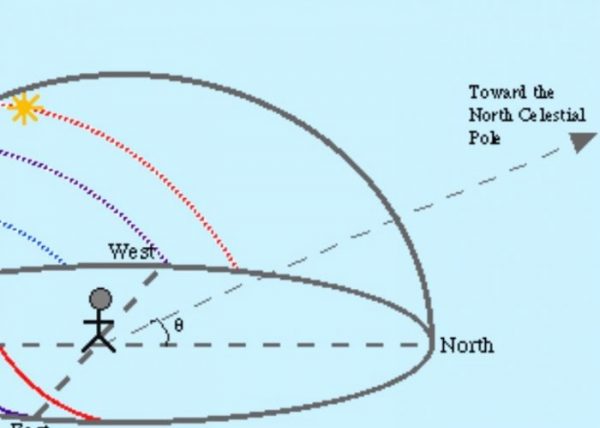

Mars orbits the sun just one step outward from Earth’s orbit. Earth takes a year to orbit the sun once. Mars takes about two years to orbit once. Opposition for Mars – when Earth passes between Mars and the sun – happens every two years and 50 days.

So Mars’ brightness waxes and wanes in our sky about every two years. But 2018 is a very, very special year for Mars. Mars will appear brighter in our sky this year than it has since 2003.

The last opposition was on May 22, 2016. Around that time, Mars was very bright indeed in Earth’s sky. See photos of Mars in May, 2016.

Joanne Richard Escober caught this image of Mars, Saturn and Antares on May 28, 2016 – around the time of Mars’ last opposition – at Apo Reef Natural Park, Occidental Mindoro, Philippines. Mars was very bright in 2016, but it’ll be even brighter in 2018!

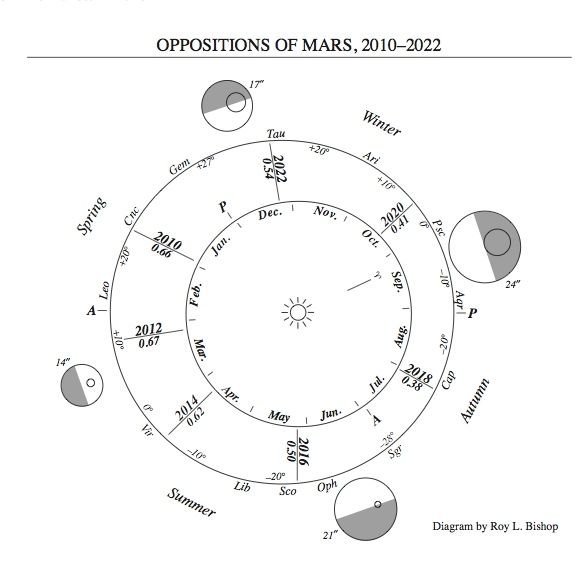

This 2018 opposition of Mars isn’t an ordinary opposition. Astronomers will call it a perihelic opposition (or perihelic apparition) of Mars. The word perihelion refers the point in Mars’ orbit when it is closest to the sun. Maybe you can see that – in years when we pass between Mars and the sun, when Mars is also closest to the sun – Earth and Mars are closest. That’s what will be happening in 2018, and it’s why the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers (ALPO) wrote:

The 2018 perihelic apparition of Mars will prove to be one of the most favorable since the 2003 apparition when the red planet came closest to Earth in 59,635 years (the year 57,617 B.C.).

According to ALPO, in 2003, Mars came within 34.6 million miles (55.7 million km) of Earth, closer than at any time in over nearly 60,000 years! It’ll be only 1.2 million miles (just under 2 million km) farther away in 2018. Closest approach for Mars in 2018 will take place on July 31, some four days after its July 27 opposition.

For a period of about two months, Mars will supplant Jupiter as the fourth brightest celestial body, after the sun, moon and Venus. Mars’ reign as the fourth-brightest celestial body (or third brightest in the nighttime sky, after the moon and Venus) will last from about July 7 to September 7.

So 2017 was, indeed, a lousy year for Mars. But just wait! Mars will be grand in 2018.

How can you find Mars throughout this year? Check out EarthSky’s monthly planet guide.

View larger. | Mars is the very bright orange object in the center of this photo, taken March 19, 2018. The Trifid Nebula is on the left, and the Lagoon Nebula is on the right, in this photo by Muzamir Mazlan. Sony A7s camera, Vixen ED103s telescope, Paramount MEII mounting, 39x30sec (ISO5000) stack with deepsky stacker and PS6.

Bottom line: Mars alternates years in appearing bright and faint in our night sky. 2017 was one of the off-years, but, in 2018, we’ll have a grand view of Mars … best since 2003!

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/21Jgj1f

Artist’s concept of Earth (3rd planet from the sun) passing between the sun and Mars (4th planet from the sun). Not to scale. At such times, Mars appears opposite the sun in our sky, and astronomers say that Mars is in “opposition” to the sun. Mars will be in opposition next in July, 2018. Image via NASA.

Remember Mars in 2003? That was the year the red planet came closer to Earth than it had been in some 60,000 years. Mars can be faint, or it can be a bright planet. It can outshine most stars. But, in 2003, for a few months, Mars was exceedingly spectacular in our sky, outshining all the stars and planets except brilliant Venus. In 2018, Mars won’t be quite as bright as it was in 2003. But nearly!

It’ll dramatically brighten over the coming months to appear as a red dot of brilliant flame in our sky around late July, 2018.

Want to see Mars now? Check out EarthSky’s planet guide

Watch for the moon to sweep past both Saturn and Mars in early June 2018.

More than any other bright planet, the appearance of Mars in our night sky changes from year to year. Its dramatic swings in brightness are part of what make Mars a fascinating planet to watch with the eye alone. Mars was faint throughout 2017. But it’s brighter now, as you might notice if you’ve been watching the planet in the predawn sky. Mars was very close to Saturn in early April (see photos), and it’s still near Saturn (though not as close) as you can see from the chart above. Jupiter is up before dawn now, too, and, when you contrast the brightness of Jupiter and Mars in April 2018, you might not believe that Mars will be brighter than Jupiter this July.

But it’s true. In late July 2018, around the time Earth sweeps between Mars and the sun, Mars will outshine Jupiter by some 1.8 times.

And that will be something to see!

See photos: A beautiful conjunction of Mars and Saturn in early April

Brighter Jupiter, fainter Mars, on January 7, 2018, via Jenney Disimon in Sabah, North Borneo. Jupiter will remain steady in brightness. Mars will brighten dramatically, to outshine Jupiter and reign as the 4th brightest object in Earth’s sky – after Venus, the moon and the sun – from about July 7 to September 7, 2018.

Mars isn’t very big, so its brightness – when it is bright – isn’t due to its bigness, as is true of Jupiter. Mars’ brightness, or lack of brightness, is all about how close it is to us. Image via Lunar and Planetary Institute.

So … why? Why does Mars sometimes appear very bright, and sometimes very faint?

The first thing to realize is that Mars isn’t a very big world. It is only 4,219 miles (6,790 km) in diameter, making it only slightly more than half as big as Earth at 7,922 miles (12,750 km) in diameter. So, when it’s bright, its brightness isn’t due to its bigness, as is the case with Jupiter.

The main reason for Mars’ extremes in brightness has to do with the proximity (or lack of proximity) of Earth and Mars during the orbits of both worlds around the sun. It’s about the nearness in space of our two worlds. Sometimes Earth and Mars are on the same side of the solar system, and hence near one another. At other times, as it was throughout most of 2017, Mars is far across the solar system from us.

On this depiction via Fourmilab – Mars is red and Earth is blue. In early October 2017, Mars was relatively far across the solar system from Earth. The distance between our 2 worlds is relatively large, so Mars appears faint.

Here’s the Fourmilab depiction for April 23, 2018. Mars is red, Earth is blue. In contrast to the chart above, you can see that Earth and Mars are now closer together. Earth is catching up to Mars in the race of the planets around the sun. Thus, Mars is getting brighter!

Earth will pass between between the sun and Mars on July 27, 2018. Then, the distance between our two worlds will be at its least for this 2-year period, and Mars will appear brightest in our sky. Image via Fourmilab.

Mars orbits the sun just one step outward from Earth’s orbit. Earth takes a year to orbit the sun once. Mars takes about two years to orbit once. Opposition for Mars – when Earth passes between Mars and the sun – happens every two years and 50 days.

So Mars’ brightness waxes and wanes in our sky about every two years. But 2018 is a very, very special year for Mars. Mars will appear brighter in our sky this year than it has since 2003.

The last opposition was on May 22, 2016. Around that time, Mars was very bright indeed in Earth’s sky. See photos of Mars in May, 2016.

Joanne Richard Escober caught this image of Mars, Saturn and Antares on May 28, 2016 – around the time of Mars’ last opposition – at Apo Reef Natural Park, Occidental Mindoro, Philippines. Mars was very bright in 2016, but it’ll be even brighter in 2018!

This 2018 opposition of Mars isn’t an ordinary opposition. Astronomers will call it a perihelic opposition (or perihelic apparition) of Mars. The word perihelion refers the point in Mars’ orbit when it is closest to the sun. Maybe you can see that – in years when we pass between Mars and the sun, when Mars is also closest to the sun – Earth and Mars are closest. That’s what will be happening in 2018, and it’s why the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers (ALPO) wrote:

The 2018 perihelic apparition of Mars will prove to be one of the most favorable since the 2003 apparition when the red planet came closest to Earth in 59,635 years (the year 57,617 B.C.).

According to ALPO, in 2003, Mars came within 34.6 million miles (55.7 million km) of Earth, closer than at any time in over nearly 60,000 years! It’ll be only 1.2 million miles (just under 2 million km) farther away in 2018. Closest approach for Mars in 2018 will take place on July 31, some four days after its July 27 opposition.

For a period of about two months, Mars will supplant Jupiter as the fourth brightest celestial body, after the sun, moon and Venus. Mars’ reign as the fourth-brightest celestial body (or third brightest in the nighttime sky, after the moon and Venus) will last from about July 7 to September 7.

So 2017 was, indeed, a lousy year for Mars. But just wait! Mars will be grand in 2018.

How can you find Mars throughout this year? Check out EarthSky’s monthly planet guide.

View larger. | Mars is the very bright orange object in the center of this photo, taken March 19, 2018. The Trifid Nebula is on the left, and the Lagoon Nebula is on the right, in this photo by Muzamir Mazlan. Sony A7s camera, Vixen ED103s telescope, Paramount MEII mounting, 39x30sec (ISO5000) stack with deepsky stacker and PS6.

Bottom line: Mars alternates years in appearing bright and faint in our night sky. 2017 was one of the off-years, but, in 2018, we’ll have a grand view of Mars … best since 2003!

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/21Jgj1f