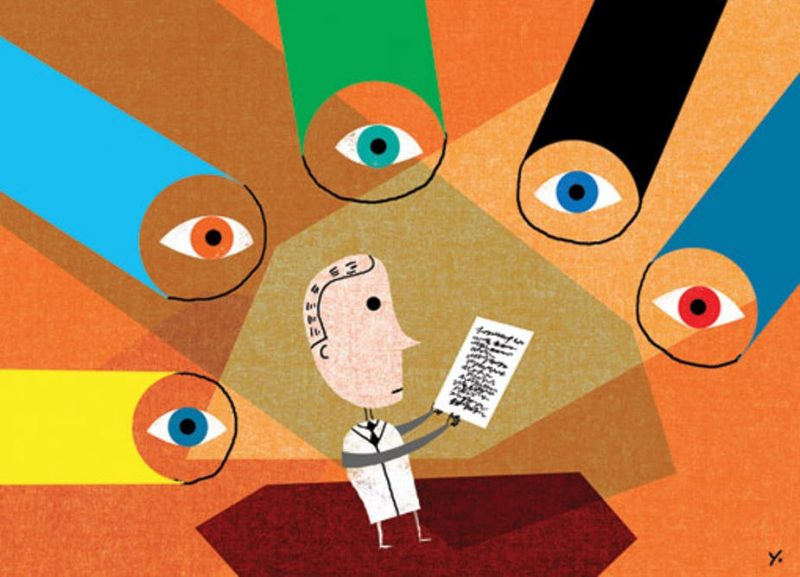

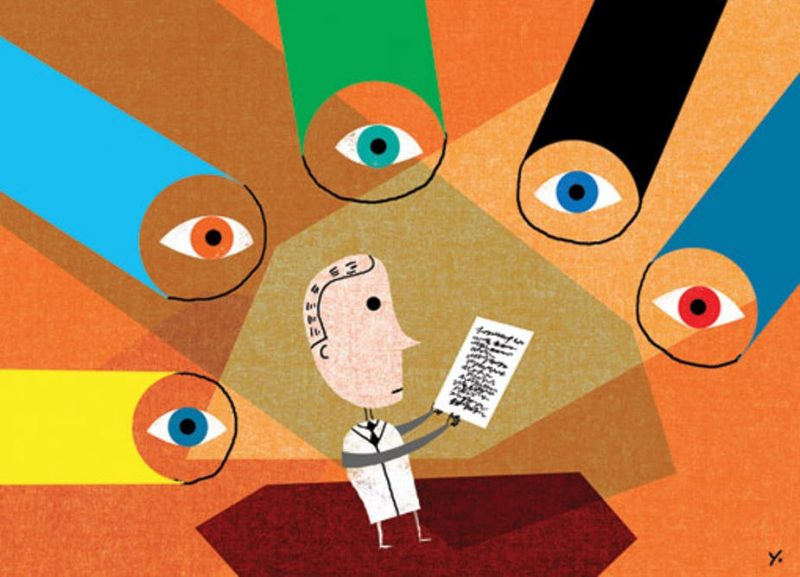

What exactly is peer review? Image via AJ Cann/Flickr.

By Andre Spicer, City, University of London and Thomas Roulet, University of Oxford

Peer review is one of the gold standards of science. It’s a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already knew.

Most scientific journals, conferences and grant applications have some sort of peer review system. In most cases it is “double blind” peer review. This means evaluators do not know the author(s), and the author(s) do not know the identity of the evaluators. The intention behind this system is to ensure evaluation is not biased.

The more prestigious the journal, conference, or grant, the more demanding will be the review process, and the more likely the rejection. This prestige is why these papers tend to be more read and more cited.

The process in details

The peer review process for journals involves at least three stages.

1. The desk evaluation stage

When a paper is submitted to a journal, it receives an initial evaluation by the chief editor, or an associate editor with relevant expertise.

At this stage, either can “desk reject” the paper: that is, reject the paper without sending it to blind referees. Generally, papers are desk rejected if the paper doesn’t fit the scope of the journal or there is a fundamental flaw which makes it unfit for publication.

In this case, the rejecting editors might write a letter summarising his or her concerns. Some journals, such as the British Medical Journal, desk reject up to two-thirds or more of the papers.

2. The blind review

If the editorial team judges there are no fundamental flaws, they send it for review to blind referees. The number of reviewers depends on the field: in finance there might be only one reviewer, while journals in other fields of social sciences might ask up to four reviewers. Those reviewers are selected by the editor on the basis of their expert knowledge and their absence of a link with the authors.

Reviewers will decide whether to reject the paper, to accept it as it is (which rarely happens) or to ask for the paper to be revised. This means the author needs to change the paper in line with the reviewers’ concerns.

Usually the reviews deal with the validity and rigour of the empirical method, and the importance and originality of the findings (what is called the “contribution” to the existing literature). The editor collects those comments, weights them, takes a decision, and writes a letter summarising the reviewers’ and his or her own concerns.

It can therefore happen that despite hostility on the part of the reviewers, the editor could offer the paper a subsequent round of revision. In the best journals in the social sciences, 10% to 20% of the papers are offered a “revise-and-resubmit” after the first round.

3. The revisions – if you are lucky enough

If the paper has not been rejected after this first round of review, it is sent back to the author(s) for a revision. The process is repeated as many times as necessary for the editor to reach a consensus point on whether to accept or reject the paper. In some cases this can last for several years.

Ultimately, less than 10% of the submitted papers are accepted in the best journals in the social sciences. The renowned journal Nature publishes around 7% of the submitted papers.

Strengths and weaknesses of the peer review process

The peer review process is seen as the gold standard in science because it ensures the rigour, novelty, and consistency of academic outputs. Typically, through rounds of review, flawed ideas are eliminated and good ideas are strengthened and improved. Peer reviewing also ensures that science is relatively independent.

Because scientific ideas are judged by other scientists, the crucial yardstick is scientific standards. If other people from outside of the field were involved in judging ideas, other criteria such as political or economic gain might be used to select ideas. Peer reviewing is also seen as a crucial way of removing personalities and bias from the process of judging knowledge.

Despite the undoubted strengths, the peer review process as we know it has been criticised. It involves a number of social interactions that might create biases – for example, authors might be identified by reviewers if they are in the same field, and desk rejections are not blind.

It might also favour incremental (adding to past research) rather than innovative (new) research. Finally, reviewers are human after all and can make mistakes, misunderstand elements, or miss errors.

Are there any alternatives?

Defenders of the peer review system say although there are flaws, we’re yet to find a better system to evaluate research. However, a number of innovations have been introduced in the academic review system to improve its objectivity and efficiency.

Some new open-access journals (such as PLOS ONE) publish papers with very little evaluation (they check the work is not deeply flawed methodologically). The focus there is on the post-publication peer review system: all readers can comment and criticise the paper.

Some journals such as Nature, have made part of the review process public (“open” review), offering a hybrid system in which peer review plays a role of primary gate keepers, but the public community of scholars judge in parallel (or afterwards in some other journals) the value of the research.

Another idea is to have a set of reviewers rating the paper each time it is revised. In this case, authors will be able to choose whether they want to invest more time in a revision to obtain a better rating, and get their work publicly recognised.

Andre Spicer, Professor of Organisational Behaviour, Cass Business School, City, University of London and Thomas Roulet, Novak Druce Research Fellow, University of Oxford

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Bottom line: What is peer review? What it actually means and how it works.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2rP9anG

What exactly is peer review? Image via AJ Cann/Flickr.

By Andre Spicer, City, University of London and Thomas Roulet, University of Oxford

Peer review is one of the gold standards of science. It’s a process where scientists (“peers”) evaluate the quality of other scientists’ work. By doing this, they aim to ensure the work is rigorous, coherent, uses past research and adds to what we already knew.

Most scientific journals, conferences and grant applications have some sort of peer review system. In most cases it is “double blind” peer review. This means evaluators do not know the author(s), and the author(s) do not know the identity of the evaluators. The intention behind this system is to ensure evaluation is not biased.

The more prestigious the journal, conference, or grant, the more demanding will be the review process, and the more likely the rejection. This prestige is why these papers tend to be more read and more cited.

The process in details

The peer review process for journals involves at least three stages.

1. The desk evaluation stage

When a paper is submitted to a journal, it receives an initial evaluation by the chief editor, or an associate editor with relevant expertise.

At this stage, either can “desk reject” the paper: that is, reject the paper without sending it to blind referees. Generally, papers are desk rejected if the paper doesn’t fit the scope of the journal or there is a fundamental flaw which makes it unfit for publication.

In this case, the rejecting editors might write a letter summarising his or her concerns. Some journals, such as the British Medical Journal, desk reject up to two-thirds or more of the papers.

2. The blind review

If the editorial team judges there are no fundamental flaws, they send it for review to blind referees. The number of reviewers depends on the field: in finance there might be only one reviewer, while journals in other fields of social sciences might ask up to four reviewers. Those reviewers are selected by the editor on the basis of their expert knowledge and their absence of a link with the authors.

Reviewers will decide whether to reject the paper, to accept it as it is (which rarely happens) or to ask for the paper to be revised. This means the author needs to change the paper in line with the reviewers’ concerns.

Usually the reviews deal with the validity and rigour of the empirical method, and the importance and originality of the findings (what is called the “contribution” to the existing literature). The editor collects those comments, weights them, takes a decision, and writes a letter summarising the reviewers’ and his or her own concerns.

It can therefore happen that despite hostility on the part of the reviewers, the editor could offer the paper a subsequent round of revision. In the best journals in the social sciences, 10% to 20% of the papers are offered a “revise-and-resubmit” after the first round.

3. The revisions – if you are lucky enough

If the paper has not been rejected after this first round of review, it is sent back to the author(s) for a revision. The process is repeated as many times as necessary for the editor to reach a consensus point on whether to accept or reject the paper. In some cases this can last for several years.

Ultimately, less than 10% of the submitted papers are accepted in the best journals in the social sciences. The renowned journal Nature publishes around 7% of the submitted papers.

Strengths and weaknesses of the peer review process

The peer review process is seen as the gold standard in science because it ensures the rigour, novelty, and consistency of academic outputs. Typically, through rounds of review, flawed ideas are eliminated and good ideas are strengthened and improved. Peer reviewing also ensures that science is relatively independent.

Because scientific ideas are judged by other scientists, the crucial yardstick is scientific standards. If other people from outside of the field were involved in judging ideas, other criteria such as political or economic gain might be used to select ideas. Peer reviewing is also seen as a crucial way of removing personalities and bias from the process of judging knowledge.

Despite the undoubted strengths, the peer review process as we know it has been criticised. It involves a number of social interactions that might create biases – for example, authors might be identified by reviewers if they are in the same field, and desk rejections are not blind.

It might also favour incremental (adding to past research) rather than innovative (new) research. Finally, reviewers are human after all and can make mistakes, misunderstand elements, or miss errors.

Are there any alternatives?

Defenders of the peer review system say although there are flaws, we’re yet to find a better system to evaluate research. However, a number of innovations have been introduced in the academic review system to improve its objectivity and efficiency.

Some new open-access journals (such as PLOS ONE) publish papers with very little evaluation (they check the work is not deeply flawed methodologically). The focus there is on the post-publication peer review system: all readers can comment and criticise the paper.

Some journals such as Nature, have made part of the review process public (“open” review), offering a hybrid system in which peer review plays a role of primary gate keepers, but the public community of scholars judge in parallel (or afterwards in some other journals) the value of the research.

Another idea is to have a set of reviewers rating the paper each time it is revised. In this case, authors will be able to choose whether they want to invest more time in a revision to obtain a better rating, and get their work publicly recognised.

Andre Spicer, Professor of Organisational Behaviour, Cass Business School, City, University of London and Thomas Roulet, Novak Druce Research Fellow, University of Oxford

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Bottom line: What is peer review? What it actually means and how it works.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2rP9anG