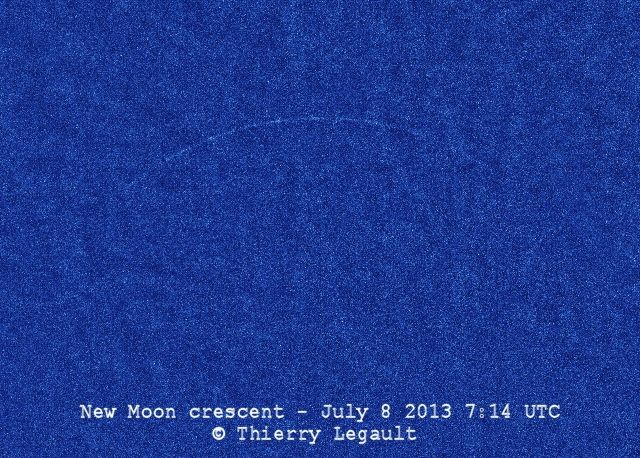

Youngest lunar crescent, with the moon’s age being exactly zero when this photo was taken — at the precise moment of the new moon – at 07:14 UTC on July 8, 2013. Image by Thierry Legault. Visit his website. Used with permission.

On July 8, 2013, a new record was set for the youngest moon ever photographed (see photos on this page). Thierry Legault – shooting from in Elancourt, France (a suburb of Paris) – captured the July 2013 moon at the precise instant it was new, or most nearly between the Earth and sun for this lunar orbit. Legault’s image (above) shows the thinnest of lunar crescents, in full daylight (naturally, since a new moon is always near the sun in the sky), at 0714 UTC on July 8, 2013. Legault said on his website:

It is the youngest possible crescent, the age of the moon at this instant being exactly zero. Celestial north is up in the image, as well as the sun. The irregularities and discontinuities are caused by the relief at the edge of the lunar disk (mountains, craters).

What is the youngest moon you can see with your eye alone?

When Legault captured the image above, the sun and moon were separated only 4.4 degrees – about 9 solar diameters – on the sky’s dome. It is extremely difficult, and risky, to try to capture the moon at such a time. Not only is the sight of our companion world drowned in bright sunlight, but there is also a risk of unintentionally glimpsing the sun and thereby damaging one’s eyesight.

That’s why Legault used a special photographic set-up to capture this youngest possible moon. He wrote on his website.

In order to reduce the glare, the images have been taken in close infrared and a pierced screen, placed just in front of the telescope, prevents the sunlight from entering directly in the telescope.

Here is Thierry Legault and his set up for capturing the youngest possible moon. See more photos and read more on his website.

What is the youngest moon you can see with your eye alone? It has long been a sport for amateur astronomers to spot the youngest moon with the eye alone. In order to see the young moon with your eye, the moon must have moved some distance from the sun on the sky’s dome. It always appears as a very slim crescent moon, seen low in the western sky for a short time after sunset. A longstanding, though somewhat doubtful record for youngest moon seen with the eye was held by two British housemaids, said to have seen the moon 14-and-three-quarter hours after new moon – in the year 1916.

A more reliable record was achieved by Stephen James O’Meara in May 1990; he saw the young crescent with the unaided eye 15 hours and 32 minutes after new moon. The record for youngest moon spotted with the eye using an optical aid passed to Mohsen Mirsaeed in 2002, who saw the moon 11 hours and 40 minutes after new moon.

But Legault’s photograph at the instant of new moon? That record can only be duplicated, not surpassed.

Very young moon like that you’re likely to see with the eye, as captured by EarthSky Facebook friend Susan Gies Jensen on February 10, 2013 in Odessa, Washington. Beautiful job, Susan! Thank you. View larger.

The moon passes more or less between the Earth and sun once each month at new moon. Then, unless you have a set-up like Thierry Legault’s, you will not see the moon because it is crossing the sky with the sun during the day. About a day after new moon, you’ll see a very thin waxing crescent moon setting shortly after the sun. The young moon appears as lighted crescent in the twilight sky, often with the darkened portion of the moon glowing dimly with earthshine.

How young a moon you can expect to see with your eye depends on the time of year and on sky conditions. It’s possible to see the youngest moons – the thinnest crescents, nearest the sunset – around the spring equinox. That would be March for the Northern Hemisphere or September for the Southern Hemisphere.

Bottom line: In our modern times, as astrophotographer Thierry Legault proved in 2013, it’s possible to capture a moon at the instant the moon is new. How about young moon sightings with the eye alone? The youngest possible moons, here.

Click here to check out Thierry Legault’s book on astrophotography.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2rPsPlr

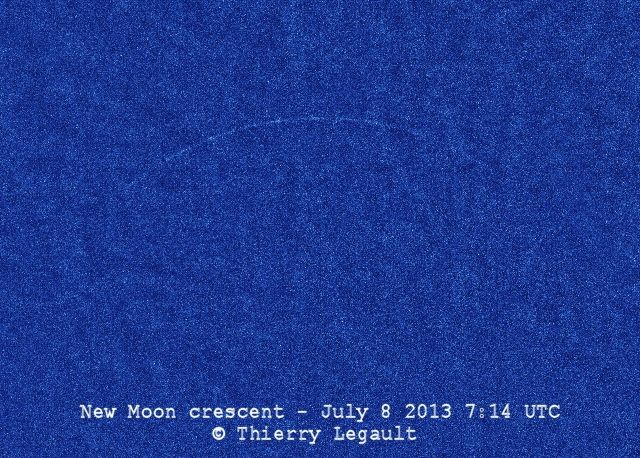

Youngest lunar crescent, with the moon’s age being exactly zero when this photo was taken — at the precise moment of the new moon – at 07:14 UTC on July 8, 2013. Image by Thierry Legault. Visit his website. Used with permission.

On July 8, 2013, a new record was set for the youngest moon ever photographed (see photos on this page). Thierry Legault – shooting from in Elancourt, France (a suburb of Paris) – captured the July 2013 moon at the precise instant it was new, or most nearly between the Earth and sun for this lunar orbit. Legault’s image (above) shows the thinnest of lunar crescents, in full daylight (naturally, since a new moon is always near the sun in the sky), at 0714 UTC on July 8, 2013. Legault said on his website:

It is the youngest possible crescent, the age of the moon at this instant being exactly zero. Celestial north is up in the image, as well as the sun. The irregularities and discontinuities are caused by the relief at the edge of the lunar disk (mountains, craters).

What is the youngest moon you can see with your eye alone?

When Legault captured the image above, the sun and moon were separated only 4.4 degrees – about 9 solar diameters – on the sky’s dome. It is extremely difficult, and risky, to try to capture the moon at such a time. Not only is the sight of our companion world drowned in bright sunlight, but there is also a risk of unintentionally glimpsing the sun and thereby damaging one’s eyesight.

That’s why Legault used a special photographic set-up to capture this youngest possible moon. He wrote on his website.

In order to reduce the glare, the images have been taken in close infrared and a pierced screen, placed just in front of the telescope, prevents the sunlight from entering directly in the telescope.

Here is Thierry Legault and his set up for capturing the youngest possible moon. See more photos and read more on his website.

What is the youngest moon you can see with your eye alone? It has long been a sport for amateur astronomers to spot the youngest moon with the eye alone. In order to see the young moon with your eye, the moon must have moved some distance from the sun on the sky’s dome. It always appears as a very slim crescent moon, seen low in the western sky for a short time after sunset. A longstanding, though somewhat doubtful record for youngest moon seen with the eye was held by two British housemaids, said to have seen the moon 14-and-three-quarter hours after new moon – in the year 1916.

A more reliable record was achieved by Stephen James O’Meara in May 1990; he saw the young crescent with the unaided eye 15 hours and 32 minutes after new moon. The record for youngest moon spotted with the eye using an optical aid passed to Mohsen Mirsaeed in 2002, who saw the moon 11 hours and 40 minutes after new moon.

But Legault’s photograph at the instant of new moon? That record can only be duplicated, not surpassed.

Very young moon like that you’re likely to see with the eye, as captured by EarthSky Facebook friend Susan Gies Jensen on February 10, 2013 in Odessa, Washington. Beautiful job, Susan! Thank you. View larger.

The moon passes more or less between the Earth and sun once each month at new moon. Then, unless you have a set-up like Thierry Legault’s, you will not see the moon because it is crossing the sky with the sun during the day. About a day after new moon, you’ll see a very thin waxing crescent moon setting shortly after the sun. The young moon appears as lighted crescent in the twilight sky, often with the darkened portion of the moon glowing dimly with earthshine.

How young a moon you can expect to see with your eye depends on the time of year and on sky conditions. It’s possible to see the youngest moons – the thinnest crescents, nearest the sunset – around the spring equinox. That would be March for the Northern Hemisphere or September for the Southern Hemisphere.

Bottom line: In our modern times, as astrophotographer Thierry Legault proved in 2013, it’s possible to capture a moon at the instant the moon is new. How about young moon sightings with the eye alone? The youngest possible moons, here.

Click here to check out Thierry Legault’s book on astrophotography.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2rPsPlr