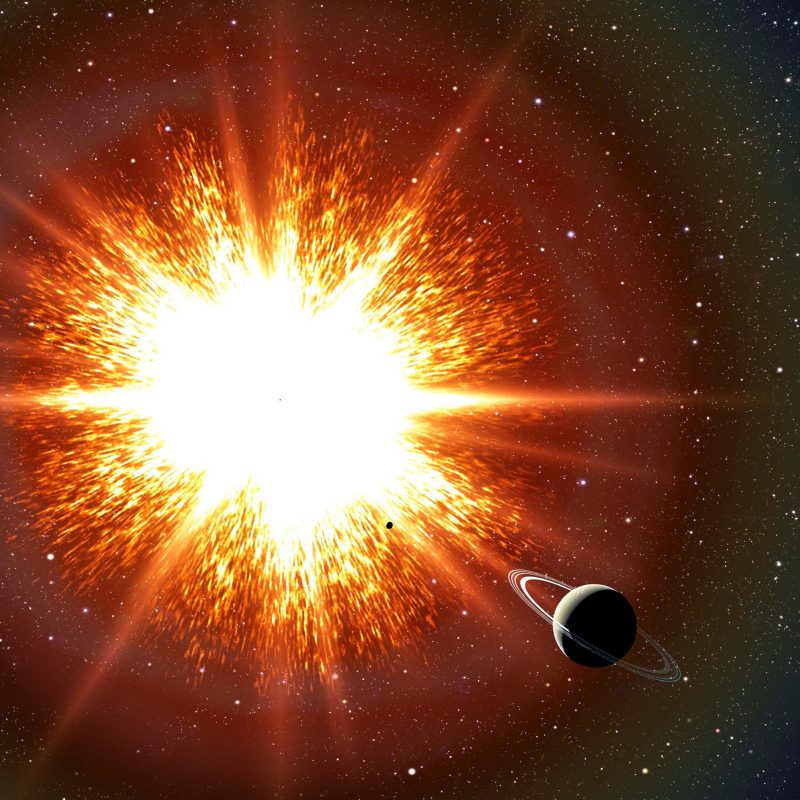

A supernova is a star explosion – destructive on a scale almost beyond human imagining. If our sun exploded as a supernova, the resulting shock wave probably wouldn’t destroy the whole Earth, but the side of Earth facing the sun would boil away. Scientists estimate that the planet as a whole would increase in temperature to roughly 15 times hotter than our normal sun’s surface. What’s more, Earth wouldn’t stay put in orbit. The sudden decrease in the sun’s mass might free the planet to wander off into space. Clearly, the sun’s distance – 8 light-minutes away – isn’t safe. Fortunately, our sun isn’t the sort of star destined to explode as a supernova. But other stars, beyond our solar system, will. What is the closest safe distance? Scientific literature cites 50 to 100 years as the closest safe distance between Earth and a supernova.

Image of remnant of Supernova 1987A as seen at optical wavelengths with the Hubble Space Telescope in 2011. This supernova was the closest in centuries, and it was visible to the eye alone. It was located on the outskirts of the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to our Milky Way. It was located approximately 168,000 light-years from Earth. Image via NASA, ESA, and P. Challis (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics).

What would happen if a supernova exploded near Earth? Let’s consider the explosion of a star besides our sun, but still at an unsafe distance. Say, the supernova is 30 light-years away. Dr. Mark Reid, a senior astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, has said:

… were a supernova to go off within about 30 light-years of us, that would lead to major effects on the Earth, possibly mass extinctions. X-rays and more energetic gamma-rays from the supernova could destroy the ozone layer that protects us from solar ultraviolet rays. It also could ionize nitrogen and oxygen in the atmosphere, leading to the formation of large amounts of smog-like nitrous oxide in the atmosphere.

What’s more, if a supernova exploded within 30 light-years, phytoplankton and reef communities would be particularly affected. Such an event severely deplete the base of the ocean food chain.

Suppose the explosion were slightly more distant. An explosion of a nearby star might leave Earth and its surface and ocean life relatively intact. But any relatively nearby explosion would still shower us with gamma rays and other high-energy radiation. This radiation could cause mutations in earthly life. Also, the radiation from a nearby supernova could change our climate.

No supernova has been known to erupt at this close distance in the known history of humankind. The most recent supernova visible to the eye was Supernova 1987A, in the year 1987. It was approximately 168,000 light-years away.

Before that, the last supernova visible to the eye was was documented by Johannes Kepler in 1604. At about 20,000 light years, it shone more brightly than any star in the night sky. It was even visible in daylight! But it didn’t cause earthly effects, as far as we know.

Relative dimensions of IK Pegasi A (left), IK Pegasi B (lower center) and our sun (right). The smallest star here is the nearest known supernova progenitor candidate, at 150 light-years away. Image via RJHall on Wikimedia Commons

How many potential supernovae are located closer to us than 50 to 100 light-years? The answer depends on the kind of supernova.

A Type II supernova is an aging massive star that collapses. There are no stars massive enough to do this located within 50 light-years of Earth.

But there are also Type I supernovae – caused by the collapse of a small faint white dwarf star. These stars are dim and hard to find, so we can’t be sure just how many are around. There are probably a few hundred of these stars within 50 light-years.

The star IK Pegasi B is the nearest known supernova progenitor candidate. It’s part of a binary star system, located about 150 light years from our sun and solar system.

The main star in the system – IK Pegasi A – is an ordinary main sequence star, not unlike our sun. The potential Type I supernova is the other star – IK Pegasi B – a massive white dwarf that’s extremely small and dense. When the A star begins to evolve into a red giant, it’s expected to grow to a radius where the white dwarf can accrete, or take on, matter from A’s expanded gaseous envelope. When the B star gets massive enough, it might collapse on itself, in the process exploding as a supernova. Read more about the IK Pegasi system from Phil Plait at Bad Astronomy.

Betelgeuse imaged in ultraviolet light by the Hubble Space Telescope and subsequently enhanced by NASA. The bright white spot is likely one of this star's poles. Image via NASA/ESA.

What about Betelgeuse? Another star often mentioned in the supernova story is Betelgeuse, one of the brightest stars in our sky, part of the famous constellation Orion. Betelgeuse is a supergiant star. It is intrinsically very brilliant.

Such brilliance comes at a price, however. Betelgeuse is one of the most famous stars in the sky because it’s due to explode someday. Betelgeuse’s enormous energy requires that the fuel be expended quickly (relatively speaking), and in fact Betelgeuse is now near the end of its lifetime. Someday soon (astronomically speaking), it will run out of fuel, collapse under its own weight, and then rebound in a spectacular Type II supernova explosion. When this happens, Betelgeuse will brighten enormously for a few weeks or months, perhaps as bright as the full moon and visible in broad daylight.

When will it happen? Probably not in our lifetimes, but no one really knowns. It could be tomorrow or a million years in the future. When it does happen, any beings on Earth will witness a spectacular event in the night sky, but earthly life won’t be harmed. That’s because Betelgeuse is 430 light-years away. Read more about Betelgeuse as a supernova.

How often do supernovae erupt in our galaxy? No one knows. Scientists have speculated that the high-energy radiation from supernovae has already caused mutations in earthly species, maybe even human beings.

One estimate suggests there might be one dangerous supernova event in Earth’s vicinity every 15 million years. Another says that, on average, a supernova explosion occurs within 10 parsecs (33 light-years) of the Earth every 240 million years. So you see we really don’t know. But you can contrast those numbers to a few million years for the time humans are thought to have existed on the planet – and four-and-a-half billion years for the age of Earth itself.

And, if you do that, you’ll see that a supernova is certain to occur near Earth – but probably not in the foreseeable future of humanity.

Bottom line: Scientific literature cites 50 to 100 years as the closest safe distance between Earth and a supernova.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2qGNR8F

A supernova is a star explosion – destructive on a scale almost beyond human imagining. If our sun exploded as a supernova, the resulting shock wave probably wouldn’t destroy the whole Earth, but the side of Earth facing the sun would boil away. Scientists estimate that the planet as a whole would increase in temperature to roughly 15 times hotter than our normal sun’s surface. What’s more, Earth wouldn’t stay put in orbit. The sudden decrease in the sun’s mass might free the planet to wander off into space. Clearly, the sun’s distance – 8 light-minutes away – isn’t safe. Fortunately, our sun isn’t the sort of star destined to explode as a supernova. But other stars, beyond our solar system, will. What is the closest safe distance? Scientific literature cites 50 to 100 years as the closest safe distance between Earth and a supernova.

Image of remnant of Supernova 1987A as seen at optical wavelengths with the Hubble Space Telescope in 2011. This supernova was the closest in centuries, and it was visible to the eye alone. It was located on the outskirts of the Tarantula Nebula in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy to our Milky Way. It was located approximately 168,000 light-years from Earth. Image via NASA, ESA, and P. Challis (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics).

What would happen if a supernova exploded near Earth? Let’s consider the explosion of a star besides our sun, but still at an unsafe distance. Say, the supernova is 30 light-years away. Dr. Mark Reid, a senior astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, has said:

… were a supernova to go off within about 30 light-years of us, that would lead to major effects on the Earth, possibly mass extinctions. X-rays and more energetic gamma-rays from the supernova could destroy the ozone layer that protects us from solar ultraviolet rays. It also could ionize nitrogen and oxygen in the atmosphere, leading to the formation of large amounts of smog-like nitrous oxide in the atmosphere.

What’s more, if a supernova exploded within 30 light-years, phytoplankton and reef communities would be particularly affected. Such an event severely deplete the base of the ocean food chain.

Suppose the explosion were slightly more distant. An explosion of a nearby star might leave Earth and its surface and ocean life relatively intact. But any relatively nearby explosion would still shower us with gamma rays and other high-energy radiation. This radiation could cause mutations in earthly life. Also, the radiation from a nearby supernova could change our climate.

No supernova has been known to erupt at this close distance in the known history of humankind. The most recent supernova visible to the eye was Supernova 1987A, in the year 1987. It was approximately 168,000 light-years away.

Before that, the last supernova visible to the eye was was documented by Johannes Kepler in 1604. At about 20,000 light years, it shone more brightly than any star in the night sky. It was even visible in daylight! But it didn’t cause earthly effects, as far as we know.

Relative dimensions of IK Pegasi A (left), IK Pegasi B (lower center) and our sun (right). The smallest star here is the nearest known supernova progenitor candidate, at 150 light-years away. Image via RJHall on Wikimedia Commons

How many potential supernovae are located closer to us than 50 to 100 light-years? The answer depends on the kind of supernova.

A Type II supernova is an aging massive star that collapses. There are no stars massive enough to do this located within 50 light-years of Earth.

But there are also Type I supernovae – caused by the collapse of a small faint white dwarf star. These stars are dim and hard to find, so we can’t be sure just how many are around. There are probably a few hundred of these stars within 50 light-years.

The star IK Pegasi B is the nearest known supernova progenitor candidate. It’s part of a binary star system, located about 150 light years from our sun and solar system.

The main star in the system – IK Pegasi A – is an ordinary main sequence star, not unlike our sun. The potential Type I supernova is the other star – IK Pegasi B – a massive white dwarf that’s extremely small and dense. When the A star begins to evolve into a red giant, it’s expected to grow to a radius where the white dwarf can accrete, or take on, matter from A’s expanded gaseous envelope. When the B star gets massive enough, it might collapse on itself, in the process exploding as a supernova. Read more about the IK Pegasi system from Phil Plait at Bad Astronomy.

Betelgeuse imaged in ultraviolet light by the Hubble Space Telescope and subsequently enhanced by NASA. The bright white spot is likely one of this star's poles. Image via NASA/ESA.

What about Betelgeuse? Another star often mentioned in the supernova story is Betelgeuse, one of the brightest stars in our sky, part of the famous constellation Orion. Betelgeuse is a supergiant star. It is intrinsically very brilliant.

Such brilliance comes at a price, however. Betelgeuse is one of the most famous stars in the sky because it’s due to explode someday. Betelgeuse’s enormous energy requires that the fuel be expended quickly (relatively speaking), and in fact Betelgeuse is now near the end of its lifetime. Someday soon (astronomically speaking), it will run out of fuel, collapse under its own weight, and then rebound in a spectacular Type II supernova explosion. When this happens, Betelgeuse will brighten enormously for a few weeks or months, perhaps as bright as the full moon and visible in broad daylight.

When will it happen? Probably not in our lifetimes, but no one really knowns. It could be tomorrow or a million years in the future. When it does happen, any beings on Earth will witness a spectacular event in the night sky, but earthly life won’t be harmed. That’s because Betelgeuse is 430 light-years away. Read more about Betelgeuse as a supernova.

How often do supernovae erupt in our galaxy? No one knows. Scientists have speculated that the high-energy radiation from supernovae has already caused mutations in earthly species, maybe even human beings.

One estimate suggests there might be one dangerous supernova event in Earth’s vicinity every 15 million years. Another says that, on average, a supernova explosion occurs within 10 parsecs (33 light-years) of the Earth every 240 million years. So you see we really don’t know. But you can contrast those numbers to a few million years for the time humans are thought to have existed on the planet – and four-and-a-half billion years for the age of Earth itself.

And, if you do that, you’ll see that a supernova is certain to occur near Earth – but probably not in the foreseeable future of humanity.

Bottom line: Scientific literature cites 50 to 100 years as the closest safe distance between Earth and a supernova.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2qGNR8F