A working paper recently published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond concludes that global warming could significantly slow economic growth in the US.

Specifically, rising summertime temperatures in the hottest states will curb economic growth. And the states with the hottest summertime temperatures are all located in the South: Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Arizona. All of these states voted for Donald Trump in 2016.

This paper is consistent with a 2015 Nature study that found an optimal temperature range for economic activity. Economies thrive in regions with an average temperature of around 14°C (57°F). Developed countries like the US, Japan, and much of Europe happen to be near that ideal temperature, but continued global warming will shift their climates away from the sweet spot and slow economic growth. The question is, by how much?

The new working paper concludes that if we meet the Paris target of staying below 2°C global warming, US economic growth will only slow by about 5 to 10%. On our current path, including climate policies implemented to date (which would lead to 3–3.5°C global warming by 2100), US economic growth would slow by about 10 to 20%. In a higher carbon pollution scenario (4°C global warming by 2100), US economic growth would slow by about 12 to 25% due to hotter temperatures alone.

Republicans have this totally wrong

House Majority Whip Steve Scalise, who represents Louisiana (the second-hottest state), recently introduced a new anti-carbon tax House Resolution. Scalise introduced similar Resolutions in 2013 with 155 co-sponsors (154 Republicans and 1 Democrat) and in 2015 with 82 co-sponsors (all Republicans). The latest version currently only has one co-sponsor, but more will undoubtedly sign on. All three versions of the Resolution include text claiming, “a carbon tax will lead to less economic growth.”

As the economics research shows, failing to curb global warming will certainly lead to less economic growth. Climate policies could hamper economic growth, but legislation can be crafted to address that concern.

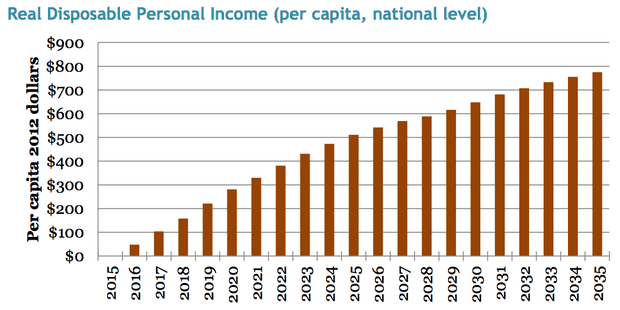

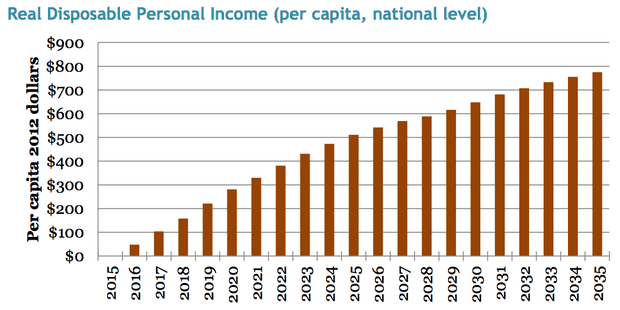

For example, as Citizens’ Climate Lobby notes in its point-by-point response to the Scalise Resolution, an economic analysis of the group’s proposed revenue-neutral carbon tax policy found that it would modestly spur economic growth(increasing national GDP by $80 to 90bn per year). With this particular policy, 100% of the carbon tax revenue is returned equally to households, and for a majority of Americans, this more than offsets their increased costs. As a result, real disposable income rises, and Americans spend that money, spurring economic growth.

Modeled change in real disposable personal income in the US resulting from the CCL rising revenue-neutral carbon tax. Illustration: Regional Economic Models, Inc.

It’s worse for poorer countries

While the Federal Reserve paper focused on the US economy, developing countries will be made much worse off by climate change. Many third world countries are located closer to the equator, where temperatures are already hotter than the temperature sweet spot identified in the 2015 Nature study. A new paperpublished last week in Science Advances also found that these poorer tropical countries will experience bigger temperature swings in a hotter world. Because of this combination of hot temperatures with bigger swings in countries with fewer resources available to adapt, these poorer nations are the most vulnerable to climate change impacts.

This is a key moral and ethical dilemma posed by global warming: as an important 2011 study concluded, the countries that have contributed the least to the problem are the most vulnerable to its consequences. Meanwhile, wealthy countries are already lagging behind their promised financial aid to help poor countries deal with climate change.

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2JWWzFJ

A working paper recently published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond concludes that global warming could significantly slow economic growth in the US.

Specifically, rising summertime temperatures in the hottest states will curb economic growth. And the states with the hottest summertime temperatures are all located in the South: Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Arkansas, and Arizona. All of these states voted for Donald Trump in 2016.

This paper is consistent with a 2015 Nature study that found an optimal temperature range for economic activity. Economies thrive in regions with an average temperature of around 14°C (57°F). Developed countries like the US, Japan, and much of Europe happen to be near that ideal temperature, but continued global warming will shift their climates away from the sweet spot and slow economic growth. The question is, by how much?

The new working paper concludes that if we meet the Paris target of staying below 2°C global warming, US economic growth will only slow by about 5 to 10%. On our current path, including climate policies implemented to date (which would lead to 3–3.5°C global warming by 2100), US economic growth would slow by about 10 to 20%. In a higher carbon pollution scenario (4°C global warming by 2100), US economic growth would slow by about 12 to 25% due to hotter temperatures alone.

Republicans have this totally wrong

House Majority Whip Steve Scalise, who represents Louisiana (the second-hottest state), recently introduced a new anti-carbon tax House Resolution. Scalise introduced similar Resolutions in 2013 with 155 co-sponsors (154 Republicans and 1 Democrat) and in 2015 with 82 co-sponsors (all Republicans). The latest version currently only has one co-sponsor, but more will undoubtedly sign on. All three versions of the Resolution include text claiming, “a carbon tax will lead to less economic growth.”

As the economics research shows, failing to curb global warming will certainly lead to less economic growth. Climate policies could hamper economic growth, but legislation can be crafted to address that concern.

For example, as Citizens’ Climate Lobby notes in its point-by-point response to the Scalise Resolution, an economic analysis of the group’s proposed revenue-neutral carbon tax policy found that it would modestly spur economic growth(increasing national GDP by $80 to 90bn per year). With this particular policy, 100% of the carbon tax revenue is returned equally to households, and for a majority of Americans, this more than offsets their increased costs. As a result, real disposable income rises, and Americans spend that money, spurring economic growth.

Modeled change in real disposable personal income in the US resulting from the CCL rising revenue-neutral carbon tax. Illustration: Regional Economic Models, Inc.

It’s worse for poorer countries

While the Federal Reserve paper focused on the US economy, developing countries will be made much worse off by climate change. Many third world countries are located closer to the equator, where temperatures are already hotter than the temperature sweet spot identified in the 2015 Nature study. A new paperpublished last week in Science Advances also found that these poorer tropical countries will experience bigger temperature swings in a hotter world. Because of this combination of hot temperatures with bigger swings in countries with fewer resources available to adapt, these poorer nations are the most vulnerable to climate change impacts.

This is a key moral and ethical dilemma posed by global warming: as an important 2011 study concluded, the countries that have contributed the least to the problem are the most vulnerable to its consequences. Meanwhile, wealthy countries are already lagging behind their promised financial aid to help poor countries deal with climate change.

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2JWWzFJ