Look for the bright waxing gibbous moon to be near the planet Saturn for several days, centered on or near August 2, 2017. Read more.

Three of the five bright planets – Jupiter, Saturn and Venus – are easy to see in August 2017. Bright Jupiter is the first “star” to pop into view at nightfall and stays out until mid-to-late evening. Golden Saturn is highest up at nightfall and stays out until late night. Brilliant Venus rises before the sun, shining in front of the constellation Gemini the Twins for most of the month. Meanwhile, Mercury will be hard to catch after sunset from northerly latitudes, yet fairly easy to spot from the Southern Hemisphere. And – for all of Earth – Mars sits deep in the glare of sunrise all month long, and probably won’t become visible in the morning sky until September 2017. Follow the links below to learn more about the planets in August 2017.

Jupiter brightest “star” in evening sky

Saturn out from dusk till late night

Venus, brilliant in east at morning dawn

Mars lost in the glare of sunrise

Mercury briefly visible after sunset

See 4 planets during the August 21 total solar eclipse

Like what EarthSky offers? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Astronomy events, star parties, festivals, workshops

Visit a new EarthSky feature – Best Places to Stargaze – and add your fav.

The waxing crescent moon shines in the vicinity of Jupiter (and the star Spica) for several days, centered on or near August 25, 2017. Read more.

Jupiter brightest “star” in evening sky. Jupiter reached opposition on April 7. That is, it was opposite the sun as seen from Earth then and so was appearing in our sky all night. The giant planet came closest to Earth for 2017 one day later, on April 8. Although Jupiter shone at its brightest and best in April, it’ll still be the brightest starlike object in the evening sky! Overall, Jupiter beams as the fourth-brightest celestial body, after the sun, moon and Venus. In August, Jupiter shines at dusk and evening; meanwhile, Venus appears only in the predawn/dawn sky.

Click here for an almanac telling you Jupiter’s setting time and Venus’ rising time in your sky.

Watch for the moon to join up with Jupiter for several days, on August 23, August 24 and August 25. See the above sky chart. Wonderful sight!

From the Northern Hemisphere, Jupiter appears fairly low in the southwest to west as darkness falls; and from the Southern Hemisphere, Jupiter appears rather high up in the sky at nightfall. From all of Earth, Jupiter sinks in a westerly direction throughout the evening, as Earth spins under the sky. In early August, at mid-northern latitudes, Jupiter sets in the west around mid-evening (roughly 10 p.m. local time or 11 p.m. daylight-saving time); and by the month’s end, Jupiter sets around nightfall (about one and one-half hours after sunset).

Jupiter stays out longer after sunset at more southerly latitudes. At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Jupiter sets in the west at late evening in early August, and around mid-evening by the month’s end.

Jupiter shines in front of the constellation Virgo, near Virgo’s sole 1st-magnitude star, called Spica.

Fernando Roquel Torres in Caguas, Puerto Rico captured Jupiter, the Great Red Spot (GRS) and all 4 of its largest moons – the Galilean satellites – on the date of Jupiter’s 2017 opposition (April 7).

If you have binoculars or a telescope, it’s fairly easy to see Jupiter’s four major moons, which look like pinpricks of light all on or near the same plane. They are often called the Galilean moons to honor Galileo, who discovered these great Jovian moons in 1610. In their order from Jupiter, these moons are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

These moons orbit Jupiter around the Jovian equator. In cycles of six years, we view Jupiter’s equator edge-on. So, in 2015, we were able to view a number of mutual events involving Jupiter’s moons, through high-powered telescopes. Starting in late 2016, Jupiter’s axis began tilting enough toward the sun and Earth so that the farthest of these four moons, Callisto, has not been passing in front of Jupiter or behind Jupiter, as seen from our vantage point. This will continue for a period of about three years, during which time Callisto is perpetually visible to those with telescopes, alternately swinging above and below Jupiter as seen from Earth.

Click here for a Jupiter’s moons almanac, courtesy of skyandtelescope.com.

James Martin in Albuquerque, New Mexico caught this wonderful photo of Saturn on its June 15, 2017 opposition.

Let the moon guide your eye to the planet Saturn and the star Antares on August 28, 29 and 30. Read more.

Saturn out from dusk till late night. Saturn reached its yearly opposition on June 15, 2017. At opposition, Saturn came closest to Earth for the year, shone brightest in our sky and stayed out all night. It was highest up at midnight (midway between sunset and sunrise).

In August 2017, Saturn shines higher in the sky at nightfall than it did in June or July. Moreover, Saturn transits – climbs its highest point for the night at dusk or early evening – a few hours earlier than it did in July 2017. So, if you’re not a night owl, August may actually present a better month for viewing Saturn, which is still shining at better than first-magnitude brightness.

Click here to find out Saturn’s transit time, when Saturn soars highest up for the night.

Look for Saturn as soon as darkness falls. It’s in the southern sky at dusk or nightfall as seen from Earth’s Northern Hemisphere, and high overhead at early evening as viewed from the Southern Hemisphere. Your best view of Saturn, from either the Northern or Southern Hemisphere, is around nightfall because that’s when Saturn is highest up for the night.

Be sure to let the moon guide you to Saturn (and the nearby star Antares) on August 2, and then again at the month’s end: August 28, August 29 and August 30.

Saturn, the farthest world that you can easily view with the eye alone, appears golden in color. It shines with a steady light.

Binoculars don’t reveal Saturn’s gorgeous rings, by the way, although binoculars will enhance Saturn’s color. To see the rings, you need a small telescope. A telescope will also reveal one or more of Saturn’s many moons, most notably Titan.

Saturn’s rings are inclined at nearly 27o from edge-on, exhibiting their northern face. In October 2017, the rings will open most widely for this year, displaying a maximum inclination of 27o.

As with so much in space (and on Earth), the appearance of Saturn’s rings from Earth is cyclical. In the year 2025, the rings will appear edge-on as seen from Earth. After that, we’ll begin to see the south side of Saturn’s rings, to increase to a maximum inclination of 27o by May 2032.

Click here for recommended almanacs; they can help you know when the planets rise, transit and set in your sky.

Jenney Disimon in Sabah, Borneo captured Venus before dawn.

The waning crescent moon swings close to the dazzling planet Venus on August 18 and 19. Read more.

Venus, brilliant in east at morning dawn Venus is always brilliant and beautiful, the brightest celestial body to light up our sky besides the sun and moon. If you’re an early bird, you can count on Venus to be your morning companion until nearly the end of 2017.

Venus reached a milestone as the morning “star” when it swung out to its greatest elongation from the sun on June 3, 2017. At this juncture, Venus was farthest from the sun on our sky’s dome, and the telescope showed Venus as half-illuminated in sunshine, like a first quarter moon. For the rest of the year, Venus will wax toward full phase.

Click here to know Venus’s present phase, remembering to select Venus as your object of interest.

Enjoy the picturesque coupling of the waning crescent moon and Venus in the eastern sky before sunrise on August 18 and August 19.

From mid-northern latitudes (U.S. and Europe), Venus rises about three hours before the sun throughout the month.

At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere (Australia and South Africa), Venus rises about two and one-half hours before sunup in early August. By the month’s end that’ll taper to about one and one-half hours.

Click here for an almanac giving rising times of Venus in your sky.

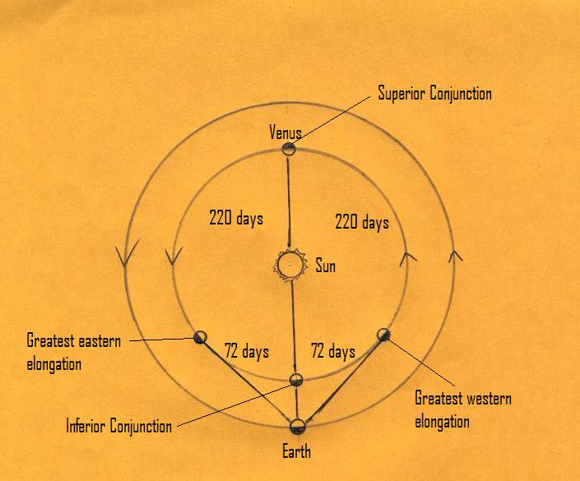

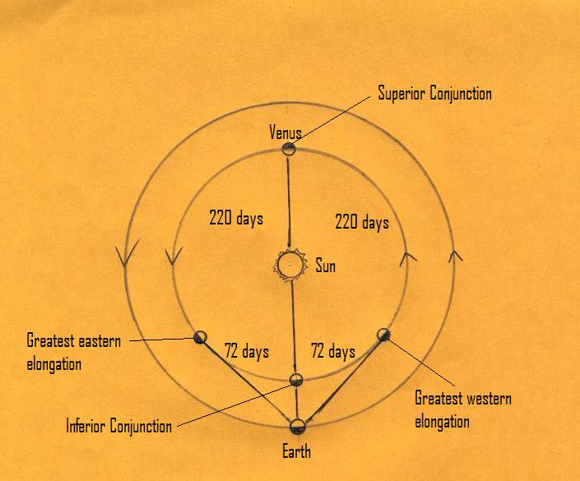

The chart below helps to illustrate why we sometimes see Venus in the evening, and sometimes before dawn.

The Earth and Venus orbit the sun counterclockwise as seen from earthly north. When Venus is to the east (left) of the Earth-sun line, we see Venus as an evening “star” in the west after sunset. After Venus reaches its inferior conjunction, Venus then moves to the west (right) of the Earth-sun line, appearing as a morning “star” in the east before sunrise.

Mars, Mercury, Earth’s moon and the dwarf planet Ceres. Mars is smaller than Earth, but bigger than our moon. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA.

Mars lost in the glare of sunrise. Mars transitioned out of the evening sky and into the morning sky on July 27, 2017, at which juncture Mars was on the far side of the sun at what astronomers call superior conjunction.

Look for Mars to emerge in the east before dawn in mid-September or October 2017. The conjunction of Mars and Venus on October 5, 2017, will likely present the first view of Mars in the morning sky for many skywatchers.

Exactly one year after Mars’s superior conjunction on July 27, 2017, Mars will swing to opposition on July 27, 2018. This will be Mars’s best opposition since the historically close opposition on August 28, 2003. In fact, Mars will become the fourth-brightest heavenly body to light up the sky in July 2018, after the sun, moon and the planet Venus. It’s not often that Mars outshines Jupiter, normally the four-brightest celestial object.

Before sunrise on September 16, 2017, draw an imaginary line from the waning crescent moon through the dazzling planet Venus to find the planets Mercury and Mars in conjunction near the horizon. Binoculars may come in handy! Read more.

Mercury briefly visible after sunset. When we say Mercury is visible in the evening sky, we’re really talking about the Southern Hemisphere. For the Southern Hemisphere, the year’s best evening apparition of Mercury happened in July 2017, but the tail end of this favorable apparition extends into the first week or two in September.

Mercury is tricky. If you look too soon after sunset, Mercury will be obscured by evening twilight; if you look too late, it will have followed the sun beneath the horizon. Watch for Mercury low in the sky, and near the sunset point on the horizon, being mindful of Mercury’s setting time.

Throughout August, Mercury will move closer to the sunset day by day, and then will pass behind the sun at superior conjunction on August 26, 2017. At superior conjunction, Mercury leaves the evening sky to enter the morning sky. The Northern Hemisphere will enjoy a favorable morning apparition of Mercury in September 2017.

For a fun sky watching challenge, try to glimpse Mercury and Mars in the east just as nightfall is giving way to dawn on or near September 16. You may need binoculars to view Mars next to Mercury!

What do we mean by bright planet? By bright planet, we mean any solar system planet that is easily visible without an optical aid and that has been watched by our ancestors since time immemorial. In their outward order from the sun, the five bright planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. These planets actually do appear bright in our sky. They are typically as bright as – or brighter than – the brightest stars. Plus, these relatively nearby worlds tend to shine with a steadier light than the distant, twinkling stars. You can spot them, and come to know them as faithful friends, if you try.

Bottom line: In August 2017, two of the five bright planets are easy to see in the evening sky: Jupiter and Saturn. Venus is found exclusively in the morning sky. Mercury shifts over into morning sky whereas Mars is lost in the glare of sunrise.

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to EarthSky News by email

Enjoy knowing where to look in the night sky? Please donate to help EarthSky keep going.

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/IJfHCr

Look for the bright waxing gibbous moon to be near the planet Saturn for several days, centered on or near August 2, 2017. Read more.

Three of the five bright planets – Jupiter, Saturn and Venus – are easy to see in August 2017. Bright Jupiter is the first “star” to pop into view at nightfall and stays out until mid-to-late evening. Golden Saturn is highest up at nightfall and stays out until late night. Brilliant Venus rises before the sun, shining in front of the constellation Gemini the Twins for most of the month. Meanwhile, Mercury will be hard to catch after sunset from northerly latitudes, yet fairly easy to spot from the Southern Hemisphere. And – for all of Earth – Mars sits deep in the glare of sunrise all month long, and probably won’t become visible in the morning sky until September 2017. Follow the links below to learn more about the planets in August 2017.

Jupiter brightest “star” in evening sky

Saturn out from dusk till late night

Venus, brilliant in east at morning dawn

Mars lost in the glare of sunrise

Mercury briefly visible after sunset

See 4 planets during the August 21 total solar eclipse

Like what EarthSky offers? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Astronomy events, star parties, festivals, workshops

Visit a new EarthSky feature – Best Places to Stargaze – and add your fav.

The waxing crescent moon shines in the vicinity of Jupiter (and the star Spica) for several days, centered on or near August 25, 2017. Read more.

Jupiter brightest “star” in evening sky. Jupiter reached opposition on April 7. That is, it was opposite the sun as seen from Earth then and so was appearing in our sky all night. The giant planet came closest to Earth for 2017 one day later, on April 8. Although Jupiter shone at its brightest and best in April, it’ll still be the brightest starlike object in the evening sky! Overall, Jupiter beams as the fourth-brightest celestial body, after the sun, moon and Venus. In August, Jupiter shines at dusk and evening; meanwhile, Venus appears only in the predawn/dawn sky.

Click here for an almanac telling you Jupiter’s setting time and Venus’ rising time in your sky.

Watch for the moon to join up with Jupiter for several days, on August 23, August 24 and August 25. See the above sky chart. Wonderful sight!

From the Northern Hemisphere, Jupiter appears fairly low in the southwest to west as darkness falls; and from the Southern Hemisphere, Jupiter appears rather high up in the sky at nightfall. From all of Earth, Jupiter sinks in a westerly direction throughout the evening, as Earth spins under the sky. In early August, at mid-northern latitudes, Jupiter sets in the west around mid-evening (roughly 10 p.m. local time or 11 p.m. daylight-saving time); and by the month’s end, Jupiter sets around nightfall (about one and one-half hours after sunset).

Jupiter stays out longer after sunset at more southerly latitudes. At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, Jupiter sets in the west at late evening in early August, and around mid-evening by the month’s end.

Jupiter shines in front of the constellation Virgo, near Virgo’s sole 1st-magnitude star, called Spica.

Fernando Roquel Torres in Caguas, Puerto Rico captured Jupiter, the Great Red Spot (GRS) and all 4 of its largest moons – the Galilean satellites – on the date of Jupiter’s 2017 opposition (April 7).

If you have binoculars or a telescope, it’s fairly easy to see Jupiter’s four major moons, which look like pinpricks of light all on or near the same plane. They are often called the Galilean moons to honor Galileo, who discovered these great Jovian moons in 1610. In their order from Jupiter, these moons are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

These moons orbit Jupiter around the Jovian equator. In cycles of six years, we view Jupiter’s equator edge-on. So, in 2015, we were able to view a number of mutual events involving Jupiter’s moons, through high-powered telescopes. Starting in late 2016, Jupiter’s axis began tilting enough toward the sun and Earth so that the farthest of these four moons, Callisto, has not been passing in front of Jupiter or behind Jupiter, as seen from our vantage point. This will continue for a period of about three years, during which time Callisto is perpetually visible to those with telescopes, alternately swinging above and below Jupiter as seen from Earth.

Click here for a Jupiter’s moons almanac, courtesy of skyandtelescope.com.

James Martin in Albuquerque, New Mexico caught this wonderful photo of Saturn on its June 15, 2017 opposition.

Let the moon guide your eye to the planet Saturn and the star Antares on August 28, 29 and 30. Read more.

Saturn out from dusk till late night. Saturn reached its yearly opposition on June 15, 2017. At opposition, Saturn came closest to Earth for the year, shone brightest in our sky and stayed out all night. It was highest up at midnight (midway between sunset and sunrise).

In August 2017, Saturn shines higher in the sky at nightfall than it did in June or July. Moreover, Saturn transits – climbs its highest point for the night at dusk or early evening – a few hours earlier than it did in July 2017. So, if you’re not a night owl, August may actually present a better month for viewing Saturn, which is still shining at better than first-magnitude brightness.

Click here to find out Saturn’s transit time, when Saturn soars highest up for the night.

Look for Saturn as soon as darkness falls. It’s in the southern sky at dusk or nightfall as seen from Earth’s Northern Hemisphere, and high overhead at early evening as viewed from the Southern Hemisphere. Your best view of Saturn, from either the Northern or Southern Hemisphere, is around nightfall because that’s when Saturn is highest up for the night.

Be sure to let the moon guide you to Saturn (and the nearby star Antares) on August 2, and then again at the month’s end: August 28, August 29 and August 30.

Saturn, the farthest world that you can easily view with the eye alone, appears golden in color. It shines with a steady light.

Binoculars don’t reveal Saturn’s gorgeous rings, by the way, although binoculars will enhance Saturn’s color. To see the rings, you need a small telescope. A telescope will also reveal one or more of Saturn’s many moons, most notably Titan.

Saturn’s rings are inclined at nearly 27o from edge-on, exhibiting their northern face. In October 2017, the rings will open most widely for this year, displaying a maximum inclination of 27o.

As with so much in space (and on Earth), the appearance of Saturn’s rings from Earth is cyclical. In the year 2025, the rings will appear edge-on as seen from Earth. After that, we’ll begin to see the south side of Saturn’s rings, to increase to a maximum inclination of 27o by May 2032.

Click here for recommended almanacs; they can help you know when the planets rise, transit and set in your sky.

Jenney Disimon in Sabah, Borneo captured Venus before dawn.

The waning crescent moon swings close to the dazzling planet Venus on August 18 and 19. Read more.

Venus, brilliant in east at morning dawn Venus is always brilliant and beautiful, the brightest celestial body to light up our sky besides the sun and moon. If you’re an early bird, you can count on Venus to be your morning companion until nearly the end of 2017.

Venus reached a milestone as the morning “star” when it swung out to its greatest elongation from the sun on June 3, 2017. At this juncture, Venus was farthest from the sun on our sky’s dome, and the telescope showed Venus as half-illuminated in sunshine, like a first quarter moon. For the rest of the year, Venus will wax toward full phase.

Click here to know Venus’s present phase, remembering to select Venus as your object of interest.

Enjoy the picturesque coupling of the waning crescent moon and Venus in the eastern sky before sunrise on August 18 and August 19.

From mid-northern latitudes (U.S. and Europe), Venus rises about three hours before the sun throughout the month.

At temperate latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere (Australia and South Africa), Venus rises about two and one-half hours before sunup in early August. By the month’s end that’ll taper to about one and one-half hours.

Click here for an almanac giving rising times of Venus in your sky.

The chart below helps to illustrate why we sometimes see Venus in the evening, and sometimes before dawn.

The Earth and Venus orbit the sun counterclockwise as seen from earthly north. When Venus is to the east (left) of the Earth-sun line, we see Venus as an evening “star” in the west after sunset. After Venus reaches its inferior conjunction, Venus then moves to the west (right) of the Earth-sun line, appearing as a morning “star” in the east before sunrise.

Mars, Mercury, Earth’s moon and the dwarf planet Ceres. Mars is smaller than Earth, but bigger than our moon. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA.

Mars lost in the glare of sunrise. Mars transitioned out of the evening sky and into the morning sky on July 27, 2017, at which juncture Mars was on the far side of the sun at what astronomers call superior conjunction.

Look for Mars to emerge in the east before dawn in mid-September or October 2017. The conjunction of Mars and Venus on October 5, 2017, will likely present the first view of Mars in the morning sky for many skywatchers.

Exactly one year after Mars’s superior conjunction on July 27, 2017, Mars will swing to opposition on July 27, 2018. This will be Mars’s best opposition since the historically close opposition on August 28, 2003. In fact, Mars will become the fourth-brightest heavenly body to light up the sky in July 2018, after the sun, moon and the planet Venus. It’s not often that Mars outshines Jupiter, normally the four-brightest celestial object.

Before sunrise on September 16, 2017, draw an imaginary line from the waning crescent moon through the dazzling planet Venus to find the planets Mercury and Mars in conjunction near the horizon. Binoculars may come in handy! Read more.

Mercury briefly visible after sunset. When we say Mercury is visible in the evening sky, we’re really talking about the Southern Hemisphere. For the Southern Hemisphere, the year’s best evening apparition of Mercury happened in July 2017, but the tail end of this favorable apparition extends into the first week or two in September.

Mercury is tricky. If you look too soon after sunset, Mercury will be obscured by evening twilight; if you look too late, it will have followed the sun beneath the horizon. Watch for Mercury low in the sky, and near the sunset point on the horizon, being mindful of Mercury’s setting time.

Throughout August, Mercury will move closer to the sunset day by day, and then will pass behind the sun at superior conjunction on August 26, 2017. At superior conjunction, Mercury leaves the evening sky to enter the morning sky. The Northern Hemisphere will enjoy a favorable morning apparition of Mercury in September 2017.

For a fun sky watching challenge, try to glimpse Mercury and Mars in the east just as nightfall is giving way to dawn on or near September 16. You may need binoculars to view Mars next to Mercury!

What do we mean by bright planet? By bright planet, we mean any solar system planet that is easily visible without an optical aid and that has been watched by our ancestors since time immemorial. In their outward order from the sun, the five bright planets are Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. These planets actually do appear bright in our sky. They are typically as bright as – or brighter than – the brightest stars. Plus, these relatively nearby worlds tend to shine with a steadier light than the distant, twinkling stars. You can spot them, and come to know them as faithful friends, if you try.

Bottom line: In August 2017, two of the five bright planets are easy to see in the evening sky: Jupiter and Saturn. Venus is found exclusively in the morning sky. Mercury shifts over into morning sky whereas Mars is lost in the glare of sunrise.

Don’t miss anything. Subscribe to EarthSky News by email

Enjoy knowing where to look in the night sky? Please donate to help EarthSky keep going.

from EarthSky http://ift.tt/IJfHCr