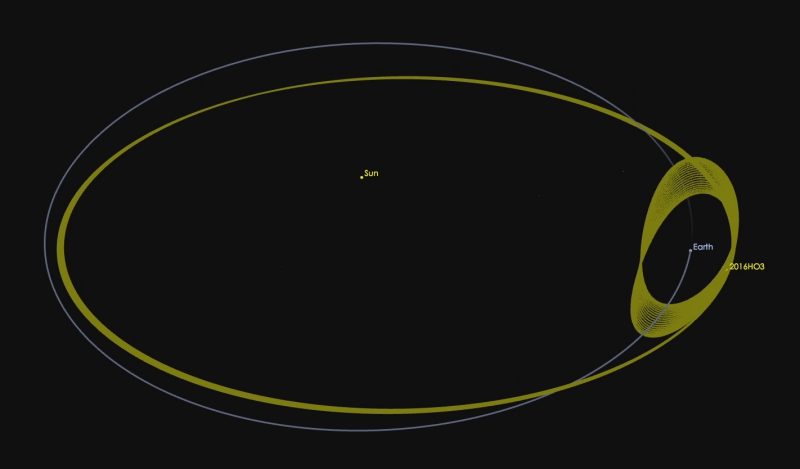

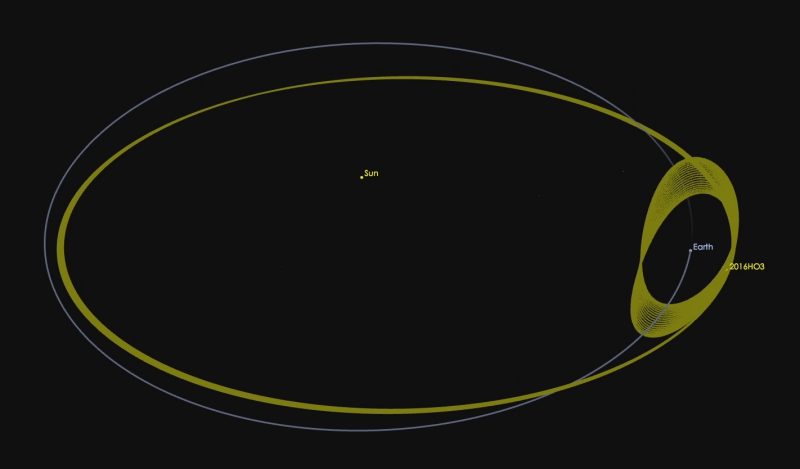

View larger. | Asteroid 2016 HO3 is a co-orbital object, or quasi-satellite. It’s a natural object whose orbit around the sun keeps it near Earth. A new study suggests it’s the perfect hiding place for an extraterrestrial probe, or “lurker.” Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/ James Benford.

Could there be alien probes “lurking” near Earth? That’s a scenario recently explored in a new paper by James Benford of Microwave Sciences. The idea is that a group of co-orbital, rocky asteroids near Earth – also known as quasi-satellites – would be the perfect place to hide a probe, in order to conduct observations of Earth undetected.

Benford’s new peer-reviewed paper discussing this possibility was published in The Astronomical Journal on September 20, 2019 (preprint here).

From the paper:

A recently discovered group of nearby co-orbital objects is an attractive location for extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) to locate a probe to observe Earth, while not being easily seen. These near-Earth objects provide an ideal way to watch our world from a secure natural object. That provides resources an ETI might need: materials, a firm anchor, concealment. These have been little studied by astronomy and not at all by SETI or planetary radar observations.

Benford goes on in his paper to describe co-orbital objects (aka quasi-satellites) found thus far and to propose both passive and active observations of them as possible sites for ET probes.

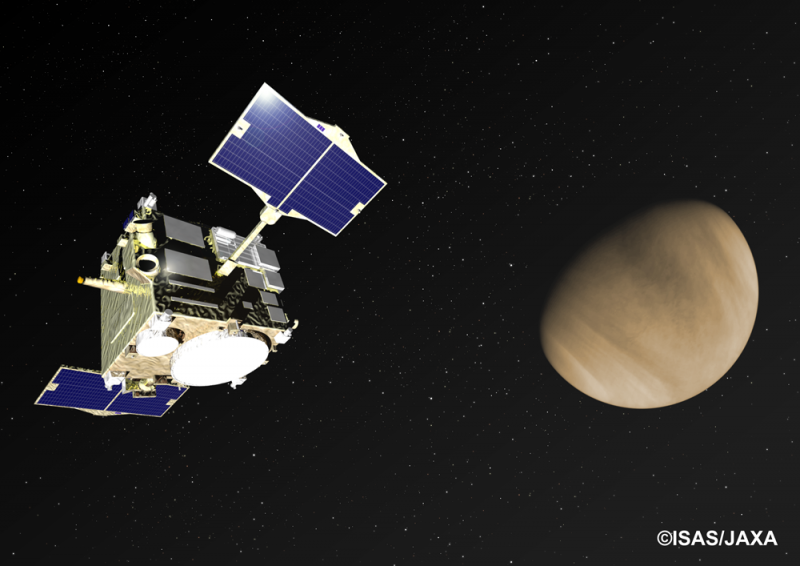

Artist’s concept of 2016 HO3, a co-orbital asteroid near Earth. Image via Inverse.

Basically, his premise is that this group of recently discovered co-orbital rocky asteroids near Earth – sharing a similar orbit to Earth’s but not orbiting Earth itself – would be an ideal location to hide an alien probe. From the vantage point of a co-orbital asteroid, the extraterrestrial civilization could gather observations of Earth while remaining hidden.

It’s an intriguing idea. Not only would these sorts of asteroids allow concealment of the probe, but they would also supply raw materials (via some kind of mining activity) and constant solar energy, if the probe needed them.

These co-orbitals have been little studied by astronomers so far, and not at all yet by SETI or planetary radar observations.

Benford calls hypothetical, hidden, unknown and unseen alien probes by the name lurkers. In theory, they would be robotic, like our own robot probes sent out to explore our solar system, but doubtless much more advanced. It’s possible that a lurker could be in our solar system, hiding on one of Earth’s co-orbital asteroids, for thousands or millions of years, just silently watching.

Benford suggests that searching for lurkers would be an interesting new type of SETI, which traditionally has focused on looking for artificial radio or light signals from distant stars. But if there were alien probes literally in our own backyard, we could actually go and observe them. Scientists could first look for them in the electromagnetic spectrum of microwaves and light or by using planetary radar.

Can you imagine finding an alien probe in our own backyard? The scene in the Stanley Kubrick’s epic 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey – where the apes first see the black monolith – comes to mind:

At the moment, the best target to explore for alien lurkers is asteroid 2016 HO3, sometimes called, Earth’s constant companion or Earth’s pet asteroid. It is the smallest, closest, and most stable (known) co-orbital. Indeed, China has announced it has plans to send a probe to 2016 HO3, on a 10-year mission that will launch in the year 2024 or later. This object is very similar to small asteroids elsewhere in the solar system. According to astronomer Vishnu Reddy:

While HO3 is close to the Earth, its small size – possibly not larger than 100 feet [30 meters] – makes it challenging target to study. Our observations show that HO3 rotates once every 28 minutes and is made of materials similar to asteroids.

Benford has also previously advocated using what he calls Benford Beacons, short microwave bursts to attract attention, kind of like lighthouses, as well as using powerful electromagnetic beams to send light spacecraft – solar sails – into the solar system for interplanetary exploration.

Earth isn’t the only planet with co-orbitals. Jupiter has two large groups of co-orbital asteroids, called the Trojans, which precede it and follow it in its orbit. Image via Paul Weigert/Western University/Gizmodo.

The lurker idea is an interesting one. It relates to the famous Fermi Paradox, which asks the question where are they? In other words, if there are highly advanced civilizations in our galaxy – technologically ahead of us by thousands or millions of years – then they could have/ should have expanded across the galaxy and found us by now. Lurkers could be a form of the sentinel hypothesis – such as Bracewell Probes – which, according to the new paper, suggests:

If advanced alien civilizations exist they might place AI monitoring devices on or near the worlds of other evolving species to track their progress. Such a robotic sentinel might establish contact with a developing race once that race had reached a certain technological threshold, such as large-scale radio communication or interplanetary flight. A probe located nearby could bide its time while our civilization developed technology that could find it, and, once contacted, could undertake a conversation in real time. Meanwhile, it could have been routinely reporting back on our biosphere and civilization for long eras.

Looking for lurkers is certainly speculative and might sound too much like science fiction to some people’s taste. But it has an appealing logic about it. And now the idea is published in a major, peer-reviewed journal.

The fact is, we don’t have a clue how an alien civilization would think. That’s why, when it comes to searching for evidence of alien intelligence, the more possibilities that can be considered, the better!

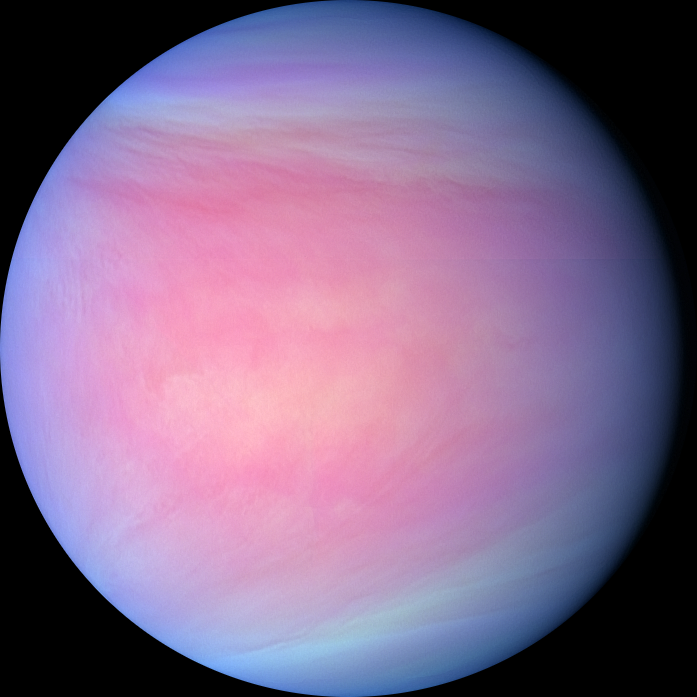

A new theory suggests that co-orbital objects or quasi-satellites – objects whose orbits around the sun keep them near Earth – would be ideal hiding places for an alien probe, or “lurker.” Image via NASA/Inverse.

Bottom line: A new study proposes searching for lurkers, alien probes that might be hiding among co-orbital rocky asteroids near Earth.

Source: Looking for Lurkers: Co-orbiters as SETI Observables

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ojDb0a

View larger. | Asteroid 2016 HO3 is a co-orbital object, or quasi-satellite. It’s a natural object whose orbit around the sun keeps it near Earth. A new study suggests it’s the perfect hiding place for an extraterrestrial probe, or “lurker.” Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/ James Benford.

Could there be alien probes “lurking” near Earth? That’s a scenario recently explored in a new paper by James Benford of Microwave Sciences. The idea is that a group of co-orbital, rocky asteroids near Earth – also known as quasi-satellites – would be the perfect place to hide a probe, in order to conduct observations of Earth undetected.

Benford’s new peer-reviewed paper discussing this possibility was published in The Astronomical Journal on September 20, 2019 (preprint here).

From the paper:

A recently discovered group of nearby co-orbital objects is an attractive location for extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) to locate a probe to observe Earth, while not being easily seen. These near-Earth objects provide an ideal way to watch our world from a secure natural object. That provides resources an ETI might need: materials, a firm anchor, concealment. These have been little studied by astronomy and not at all by SETI or planetary radar observations.

Benford goes on in his paper to describe co-orbital objects (aka quasi-satellites) found thus far and to propose both passive and active observations of them as possible sites for ET probes.

Artist’s concept of 2016 HO3, a co-orbital asteroid near Earth. Image via Inverse.

Basically, his premise is that this group of recently discovered co-orbital rocky asteroids near Earth – sharing a similar orbit to Earth’s but not orbiting Earth itself – would be an ideal location to hide an alien probe. From the vantage point of a co-orbital asteroid, the extraterrestrial civilization could gather observations of Earth while remaining hidden.

It’s an intriguing idea. Not only would these sorts of asteroids allow concealment of the probe, but they would also supply raw materials (via some kind of mining activity) and constant solar energy, if the probe needed them.

These co-orbitals have been little studied by astronomers so far, and not at all yet by SETI or planetary radar observations.

Benford calls hypothetical, hidden, unknown and unseen alien probes by the name lurkers. In theory, they would be robotic, like our own robot probes sent out to explore our solar system, but doubtless much more advanced. It’s possible that a lurker could be in our solar system, hiding on one of Earth’s co-orbital asteroids, for thousands or millions of years, just silently watching.

Benford suggests that searching for lurkers would be an interesting new type of SETI, which traditionally has focused on looking for artificial radio or light signals from distant stars. But if there were alien probes literally in our own backyard, we could actually go and observe them. Scientists could first look for them in the electromagnetic spectrum of microwaves and light or by using planetary radar.

Can you imagine finding an alien probe in our own backyard? The scene in the Stanley Kubrick’s epic 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey – where the apes first see the black monolith – comes to mind:

At the moment, the best target to explore for alien lurkers is asteroid 2016 HO3, sometimes called, Earth’s constant companion or Earth’s pet asteroid. It is the smallest, closest, and most stable (known) co-orbital. Indeed, China has announced it has plans to send a probe to 2016 HO3, on a 10-year mission that will launch in the year 2024 or later. This object is very similar to small asteroids elsewhere in the solar system. According to astronomer Vishnu Reddy:

While HO3 is close to the Earth, its small size – possibly not larger than 100 feet [30 meters] – makes it challenging target to study. Our observations show that HO3 rotates once every 28 minutes and is made of materials similar to asteroids.

Benford has also previously advocated using what he calls Benford Beacons, short microwave bursts to attract attention, kind of like lighthouses, as well as using powerful electromagnetic beams to send light spacecraft – solar sails – into the solar system for interplanetary exploration.

Earth isn’t the only planet with co-orbitals. Jupiter has two large groups of co-orbital asteroids, called the Trojans, which precede it and follow it in its orbit. Image via Paul Weigert/Western University/Gizmodo.

The lurker idea is an interesting one. It relates to the famous Fermi Paradox, which asks the question where are they? In other words, if there are highly advanced civilizations in our galaxy – technologically ahead of us by thousands or millions of years – then they could have/ should have expanded across the galaxy and found us by now. Lurkers could be a form of the sentinel hypothesis – such as Bracewell Probes – which, according to the new paper, suggests:

If advanced alien civilizations exist they might place AI monitoring devices on or near the worlds of other evolving species to track their progress. Such a robotic sentinel might establish contact with a developing race once that race had reached a certain technological threshold, such as large-scale radio communication or interplanetary flight. A probe located nearby could bide its time while our civilization developed technology that could find it, and, once contacted, could undertake a conversation in real time. Meanwhile, it could have been routinely reporting back on our biosphere and civilization for long eras.

Looking for lurkers is certainly speculative and might sound too much like science fiction to some people’s taste. But it has an appealing logic about it. And now the idea is published in a major, peer-reviewed journal.

The fact is, we don’t have a clue how an alien civilization would think. That’s why, when it comes to searching for evidence of alien intelligence, the more possibilities that can be considered, the better!

A new theory suggests that co-orbital objects or quasi-satellites – objects whose orbits around the sun keep them near Earth – would be ideal hiding places for an alien probe, or “lurker.” Image via NASA/Inverse.

Bottom line: A new study proposes searching for lurkers, alien probes that might be hiding among co-orbital rocky asteroids near Earth.

Source: Looking for Lurkers: Co-orbiters as SETI Observables

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2ojDb0a