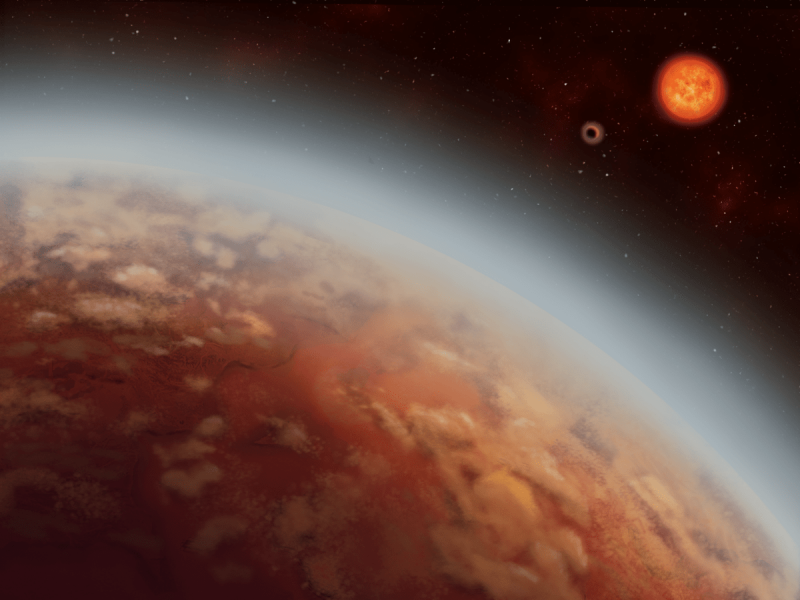

Artist’s concept of K2-18b, as well as another planet in this system, K2-18c, with the parent star, a red dwarf, in the background. Image via Alex Boersma/iREx.

A couple of days ago, EarthSky reported that for the first time ever, water vapor had been detected in the atmosphere of a potentially habitable super-Earth exoplanet. We weren’t alone in our report. As might be expected, the finding received a lot of attention from media. But, it turns out, that the story might not be quite as first reported and was mis-characterized to some extent.

The discovery was outlined in two different papers, the first one published on ArXiv on September 10, 2019 and the second in Nature Astronomy on September 11, 2019.

The papers detail the finding of water vapor in the atmosphere of K2-18b, an exoplanet in the habitable zone of its star – where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist – 110 light-years from Earth. It’s accurate that this is the first time that water vapor has been identified in the atmosphere of a smaller exoplanet (non-gas-giant) in the habitable zone of its star, but soon after the announcement, many planetary scientists critiqued how the discovery was covered in media and social media.

The water vapor detection itself is confirmed, but there is a lot of debate as to just what kind of planet K2-18b actually is, and how habitable it may be (or not).

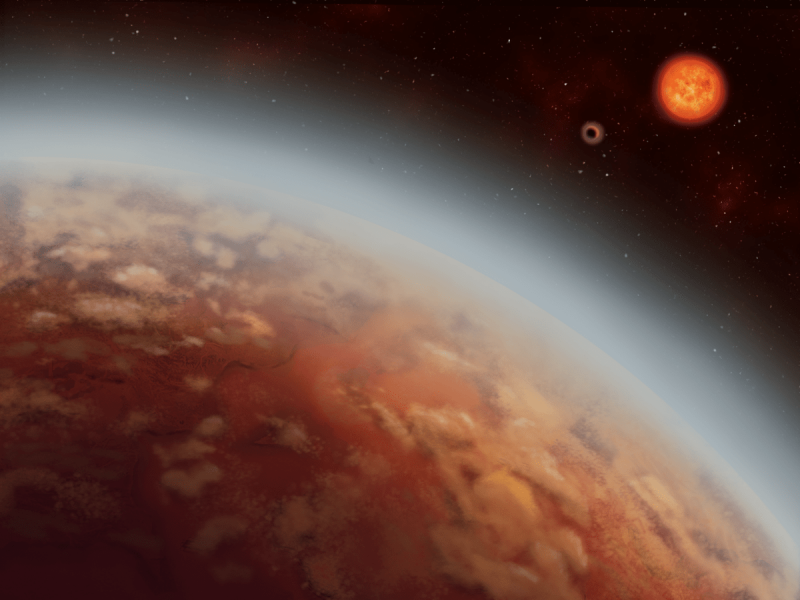

Another artist’s concept of super-Earth K2-18b. Scientists have detected water vapor in its atmosphere, but is it habitable? Most scientists say it’s unlikely. Image via ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser/UCL News.

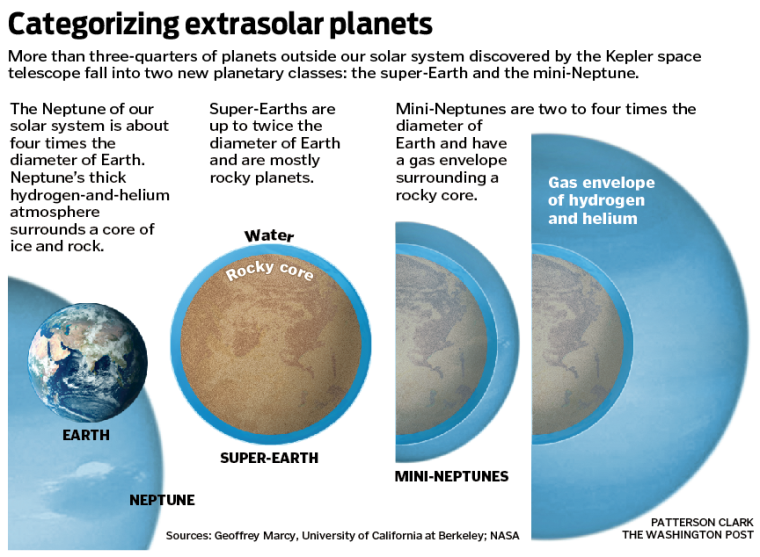

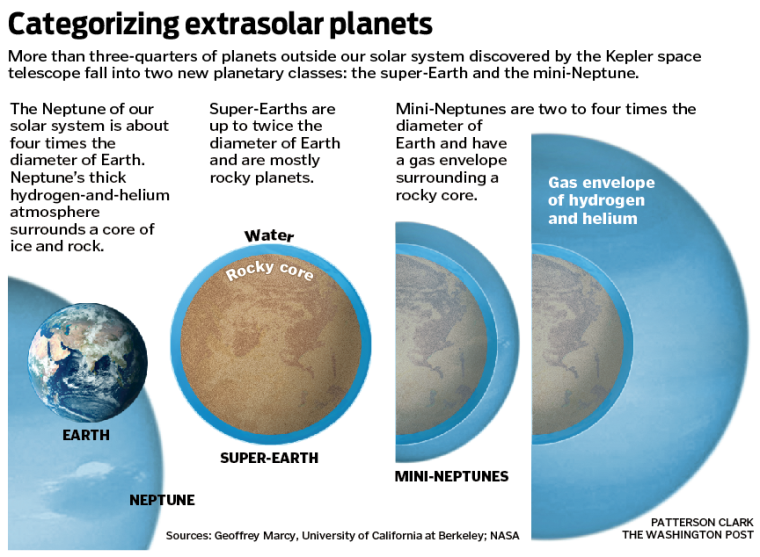

Some scientists, including in the Nature Astronomy paper, have referred to the planet as a super-Earth. A super-Earth is larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune – typically up to about a maximum of twice the size of Earth – and many have been discovered already. Most are thought to be rocky, like Earth, but there is a transition point – starting about 1.6 – two times Earth’s radius – where a planet can become a mini-gas-giant, or a mini-Neptune as they are usually called. They are larger than super-Earths, but still smaller than Neptune. Most scientists now consider K2-18b to be a mini-Neptune, not a super-Earth, with a deep atmosphere of hydrogen and/or helium, and possibly no solid surface at all.

K2-18b has a radius of about 2.7 times that of Earth, and a mass about nine times that of Earth. While some scientists would still consider that to be a possible super-Earth, most it seems would classify it as a mini-Neptune. All of this can be a bit confusing.

The 2017 study previously linked to considered that K2-18b might be either large and rocky or covered with water and/or ice. But that study didn’t account for atmospheric constraints, only mass and radius. As exoplanet scientist Erin May told me on Twitter:

My PhD partially focused on the distinction between these classes of planets. Many studies show that it’s extremely difficult to make a planet > than 2 Earth-radii without a large atmosphere. Mass & radius (density) alone are actually not very useful here. I’d also like to point out that from mass and radius alone, this planet should have never been considered a super-Earth. I think there’s a tendency to throw this term around because it’s more “exciting”, but we as astronomers need to keep our terminology straight.

Néstor Espinoza, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), also told me:

If you believe the water feature, you have to believe it is an H/He dominated atmosphere so yes. And the source you cite is not “outdated” – at that time we just didn’t have atmospheric constraints, only mass and radius. Also: the very fact that we see a water feature *implies* a H/He dominated atmosphere. There is no way around it.

There is a good Twitter thread about all this here, from Jessie Christiansen, a research scientist at NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExScI):

GUYS. Two independent announcements today of the same thing: We have found water vapor in the atmosphere of a planet called K2-18 b!

BUT WAIT?

WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

— Dr. Jessie Christiansen (@aussiastronomer) September 11, 2019

Also from Nature correspondent Alexandra Witze:

Some news today about K2-18b, a small planet 110 light-years from Earth. Hubble has spotted water vapor & possibly clouds in its atmosphere. https://t.co/3alGmHq9wS

— Alexandra Witze (@alexwitze) September 11, 2019

The planet is more of a mini-Neptune than a super-Earth: it's got a thick hydrogen atmosphere and if you want to find the water you'd have to go ballooning. But, the work is pushing the limits of understanding these alien worlds and how like (or unlike) Earth they may be.

— Alexandra Witze (@alexwitze) September 11, 2019

And another thread, from Marina Koren at The Atlantic:

1/ A thread about the big exoplanet news that was announced today, which—to be perfectly honest—was challenging for me to parse and report.. https://t.co/J1rstNGrpR

— Marina Koren (@marinakoren) September 11, 2019

So what about habitability? Since the planet is considered – by most scientists – to now be a mini-Neptune, this lowers the chances significantly. Water vapor itself, or even rain (as still considered possible in this planet’s atmosphere), is great, but life-as-we-know-it requires a rocky surface/interior for chemical nutrients, and bodies of liquid water. There may indeed be planets out there with life forms in only a gaseous atmosphere, but for Earth-kind of life at least, K2-18b would seem to be ill-suited for this.

There has been a lot of debate over whether K2-18b is a super-Earth or mini-Neptune. Most scientists now agree that it is a mini-Neptune, making habitability much less likely. Image via Patterson Clark/Washington Post/Quora.

Finding evidence for water vapor on a distant exoplanet in its star’s habitable zone is exciting, but in itself not proof of habitability. There are many factors that need to be considered, including composition of the planet and its atmosphere. However, K2-18b is the smallest exoplanet so far found to have water vapor in its atmosphere, which is a good sign: it supports the contention of scientists that even smaller planets with water vapor and/or liquid water will be found, worlds that are more Earth-like in terms of both size and composition. Upcoming space-based telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will be able to study the atmospheres of planets like this, and smaller, in greater detail than ever before, and even search for biosignatures, which could be evidence for life.

Bottom line: The exoplanet K2-18b does have water vapor in its atmosphere, but the planet itself is probably very un-Earth-like.

Source: Water vapour in the atmosphere of the habitable-zone eight-Earth-mass planet K2-18 b

Source: Water Vapor on the Habitable-Zone Exoplanet K2-18b

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/34Lknrn

Artist’s concept of K2-18b, as well as another planet in this system, K2-18c, with the parent star, a red dwarf, in the background. Image via Alex Boersma/iREx.

A couple of days ago, EarthSky reported that for the first time ever, water vapor had been detected in the atmosphere of a potentially habitable super-Earth exoplanet. We weren’t alone in our report. As might be expected, the finding received a lot of attention from media. But, it turns out, that the story might not be quite as first reported and was mis-characterized to some extent.

The discovery was outlined in two different papers, the first one published on ArXiv on September 10, 2019 and the second in Nature Astronomy on September 11, 2019.

The papers detail the finding of water vapor in the atmosphere of K2-18b, an exoplanet in the habitable zone of its star – where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist – 110 light-years from Earth. It’s accurate that this is the first time that water vapor has been identified in the atmosphere of a smaller exoplanet (non-gas-giant) in the habitable zone of its star, but soon after the announcement, many planetary scientists critiqued how the discovery was covered in media and social media.

The water vapor detection itself is confirmed, but there is a lot of debate as to just what kind of planet K2-18b actually is, and how habitable it may be (or not).

Another artist’s concept of super-Earth K2-18b. Scientists have detected water vapor in its atmosphere, but is it habitable? Most scientists say it’s unlikely. Image via ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser/UCL News.

Some scientists, including in the Nature Astronomy paper, have referred to the planet as a super-Earth. A super-Earth is larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune – typically up to about a maximum of twice the size of Earth – and many have been discovered already. Most are thought to be rocky, like Earth, but there is a transition point – starting about 1.6 – two times Earth’s radius – where a planet can become a mini-gas-giant, or a mini-Neptune as they are usually called. They are larger than super-Earths, but still smaller than Neptune. Most scientists now consider K2-18b to be a mini-Neptune, not a super-Earth, with a deep atmosphere of hydrogen and/or helium, and possibly no solid surface at all.

K2-18b has a radius of about 2.7 times that of Earth, and a mass about nine times that of Earth. While some scientists would still consider that to be a possible super-Earth, most it seems would classify it as a mini-Neptune. All of this can be a bit confusing.

The 2017 study previously linked to considered that K2-18b might be either large and rocky or covered with water and/or ice. But that study didn’t account for atmospheric constraints, only mass and radius. As exoplanet scientist Erin May told me on Twitter:

My PhD partially focused on the distinction between these classes of planets. Many studies show that it’s extremely difficult to make a planet > than 2 Earth-radii without a large atmosphere. Mass & radius (density) alone are actually not very useful here. I’d also like to point out that from mass and radius alone, this planet should have never been considered a super-Earth. I think there’s a tendency to throw this term around because it’s more “exciting”, but we as astronomers need to keep our terminology straight.

Néstor Espinoza, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), also told me:

If you believe the water feature, you have to believe it is an H/He dominated atmosphere so yes. And the source you cite is not “outdated” – at that time we just didn’t have atmospheric constraints, only mass and radius. Also: the very fact that we see a water feature *implies* a H/He dominated atmosphere. There is no way around it.

There is a good Twitter thread about all this here, from Jessie Christiansen, a research scientist at NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExScI):

GUYS. Two independent announcements today of the same thing: We have found water vapor in the atmosphere of a planet called K2-18 b!

BUT WAIT?

WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

— Dr. Jessie Christiansen (@aussiastronomer) September 11, 2019

Also from Nature correspondent Alexandra Witze:

Some news today about K2-18b, a small planet 110 light-years from Earth. Hubble has spotted water vapor & possibly clouds in its atmosphere. https://t.co/3alGmHq9wS

— Alexandra Witze (@alexwitze) September 11, 2019

The planet is more of a mini-Neptune than a super-Earth: it's got a thick hydrogen atmosphere and if you want to find the water you'd have to go ballooning. But, the work is pushing the limits of understanding these alien worlds and how like (or unlike) Earth they may be.

— Alexandra Witze (@alexwitze) September 11, 2019

And another thread, from Marina Koren at The Atlantic:

1/ A thread about the big exoplanet news that was announced today, which—to be perfectly honest—was challenging for me to parse and report.. https://t.co/J1rstNGrpR

— Marina Koren (@marinakoren) September 11, 2019

So what about habitability? Since the planet is considered – by most scientists – to now be a mini-Neptune, this lowers the chances significantly. Water vapor itself, or even rain (as still considered possible in this planet’s atmosphere), is great, but life-as-we-know-it requires a rocky surface/interior for chemical nutrients, and bodies of liquid water. There may indeed be planets out there with life forms in only a gaseous atmosphere, but for Earth-kind of life at least, K2-18b would seem to be ill-suited for this.

There has been a lot of debate over whether K2-18b is a super-Earth or mini-Neptune. Most scientists now agree that it is a mini-Neptune, making habitability much less likely. Image via Patterson Clark/Washington Post/Quora.

Finding evidence for water vapor on a distant exoplanet in its star’s habitable zone is exciting, but in itself not proof of habitability. There are many factors that need to be considered, including composition of the planet and its atmosphere. However, K2-18b is the smallest exoplanet so far found to have water vapor in its atmosphere, which is a good sign: it supports the contention of scientists that even smaller planets with water vapor and/or liquid water will be found, worlds that are more Earth-like in terms of both size and composition. Upcoming space-based telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) will be able to study the atmospheres of planets like this, and smaller, in greater detail than ever before, and even search for biosignatures, which could be evidence for life.

Bottom line: The exoplanet K2-18b does have water vapor in its atmosphere, but the planet itself is probably very un-Earth-like.

Source: Water vapour in the atmosphere of the habitable-zone eight-Earth-mass planet K2-18 b

Source: Water Vapor on the Habitable-Zone Exoplanet K2-18b

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/34Lknrn