Mars is a rocky world, and some scientists have theorized that erosion by wind causes Mars rocks to produce methane. But a new study from Newcastle University refutes that. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Phys.org.

What is producing methane on Mars? That is a question that scientists have been trying to answer for quite some time now. There are various possibilities, both geological and biological, but narrowing them down has been a challenge. Could it really be a sign of … life? Now, a new study has shown that at least one of the geological scenarios is very unlikely: wind erosion of rocks.

Researchers at Newcastle University in the U.K. published their peer-reviewed findings in Scientific Reports on June 3, 2019, and a new press release was issued on August 12, 2019. From the article abstract:

Seasonal changes in methane background levels and methane spikes have been detected in situ a metre above the martian surface, and larger methane plumes detected via ground-based remote sensing, however their origin have not yet been adequately explained. Proposed methane sources include the UV irradiation of meteoritic-derived organic matter, hydrothermal reactions with olivine, organic breakdown via meteoroid impact, release from gas hydrates, biological production, or the release of methane from fluid inclusions in basalt during aeolian erosion. Here we quantify for the first time the potential importance of aeolian abrasion as a mechanism for releasing trapped methane from within rocks, by coupling estimates of present day surface wind abrasion with the methane contents of a variety of martian meteorites, analogue terrestrial basalts and analogue terrestrial sedimentary rocks. We demonstrate that the abrasion of basalt under present day Martian rates of aeolian erosion is highly unlikely to produce detectable changes in methane concentrations in the atmosphere. We further show that, although there is a greater potential for methane production from the aeolian abrasion of certain sedimentary rocks, to produce the magnitude of methane concentrations analysed by the Curiosity rover they would have to contain methane in similar concentrations as economic reserved of biogenic/thermogenic deposits on Earth. Therefore we suggest that aeolian abrasion is an unlikely origin of the methane detected in the martian atmosphere, and that other methane sources are required.

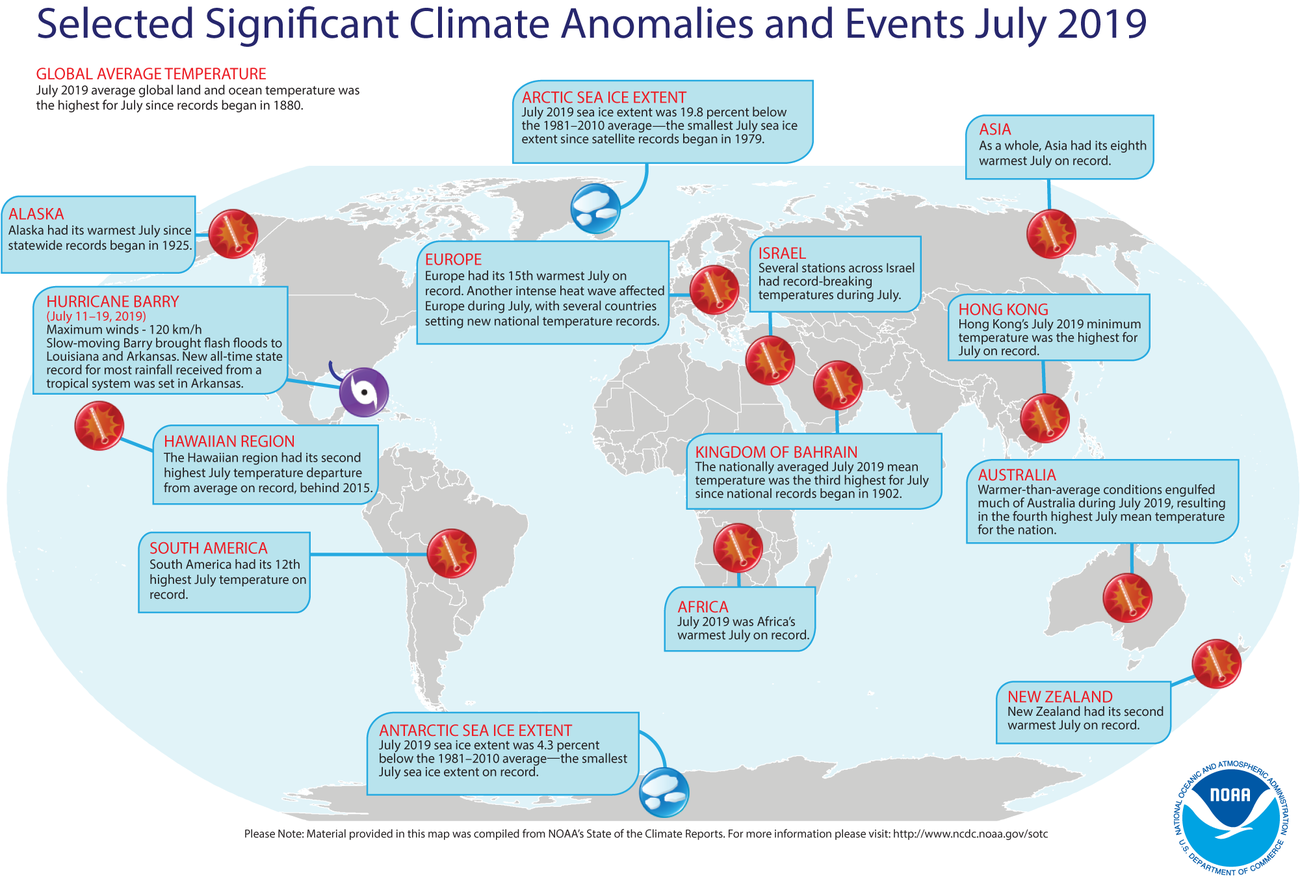

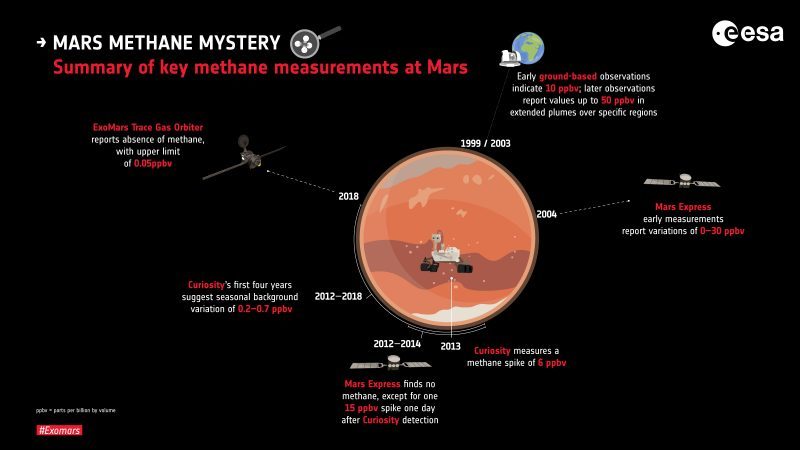

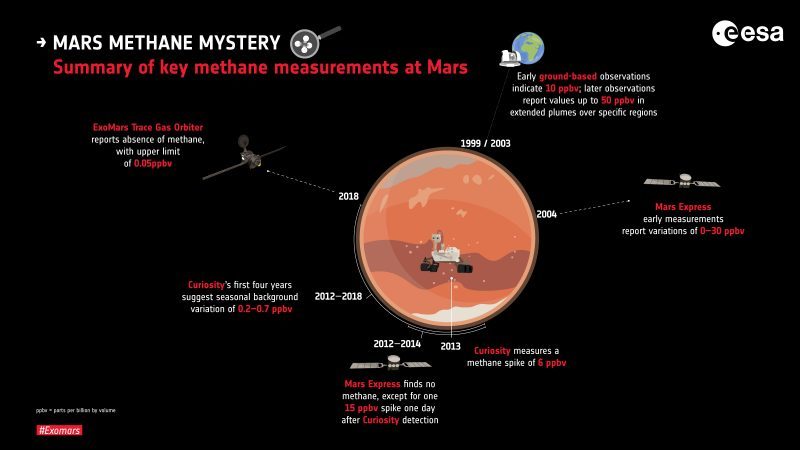

A history of key methane measurements on Mars from 1999 to 2018. Image via ESA.

One of the more recent theories was that wind erosion of rocks could produce the methane detected in the lower atmosphere. But the team’s findings showed that it wouldn’t be able to produce methane in the amounts observed, according to Jon Telling, a geochemist at Newcastle University:

The questions are – where is this methane coming from, and is the source biological? That’s a massive question and to get to the answer we need to rule out lots of other factors first.

We realized one potential source of the methane that people hadn’t really looked at in any detail before was wind erosion, releasing gases trapped within rocks. High resolution imagery from orbit over the last decade have shown that winds on Mars can drive much higher local rates of sand movement, and hence potential rates of sand erosion, than previously recognised.

In fact, in a few cases, the rate of erosion is estimated to be comparable to those of cold and arid sand dune fields on Earth.

Using the data available, we estimated rates of erosion on the surface of Mars and how important it could be in releasing methane.

And taking all that into account we found it was very unlikely to be the source.

What’s important about this is that it strengthens the argument that the methane must be coming from a different source. Whether or not that’s biological, we still don’t know.

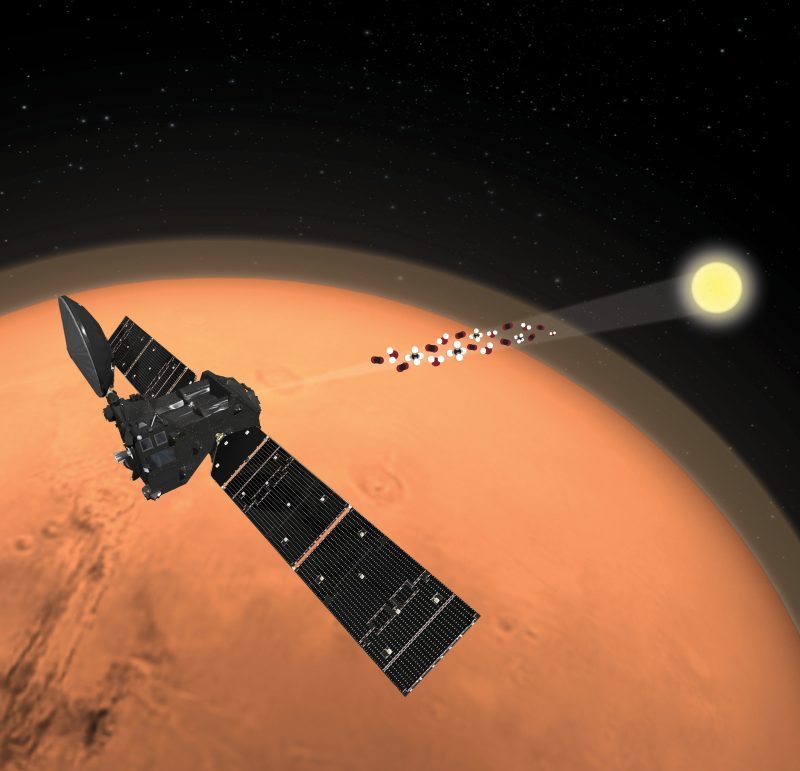

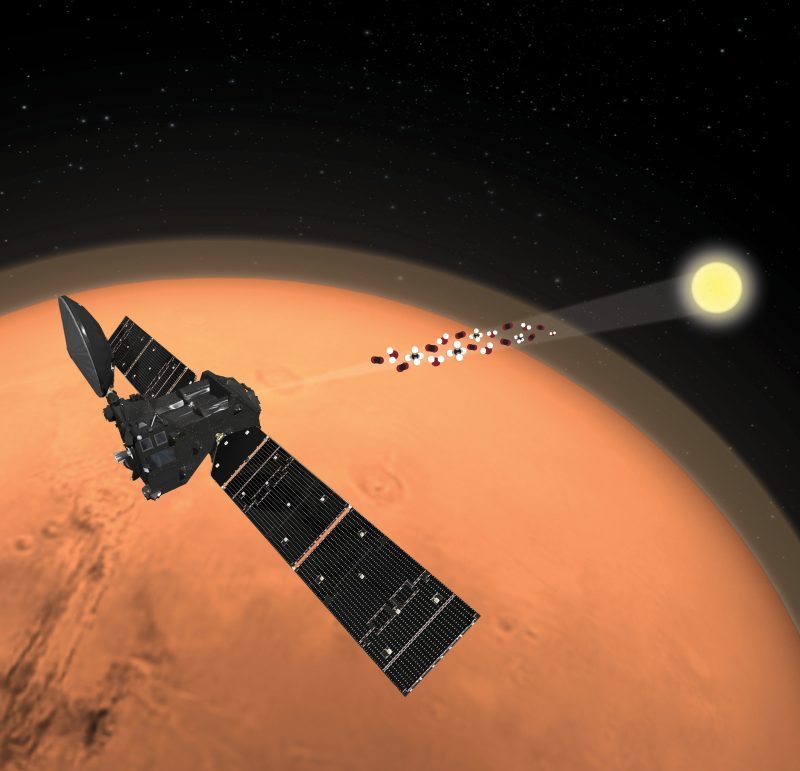

Artist’s concept of ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter, part of the ExoMars mission, analyzing the Martian atmosphere. Image via ESA/ATG MediaLab.

Observations from both orbiting spacecraft and the Curiosity rover, as well as telescopes on Earth, have shown that methane levels in the Martian atmosphere appear to be seasonal, peaking in the summer and fading again in the winter. Just why that is isn’t known yet, but it indicates a regular process is occurring, whether geological or biological. Oddly, ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) hasn’t detected any methane yet, although that is one of its main objectives. But that may simply be because of the seasonality of the methane, or because TGO focuses its observations on the upper levels of the atmosphere, and most of the other methane detections have been closer to the ground.

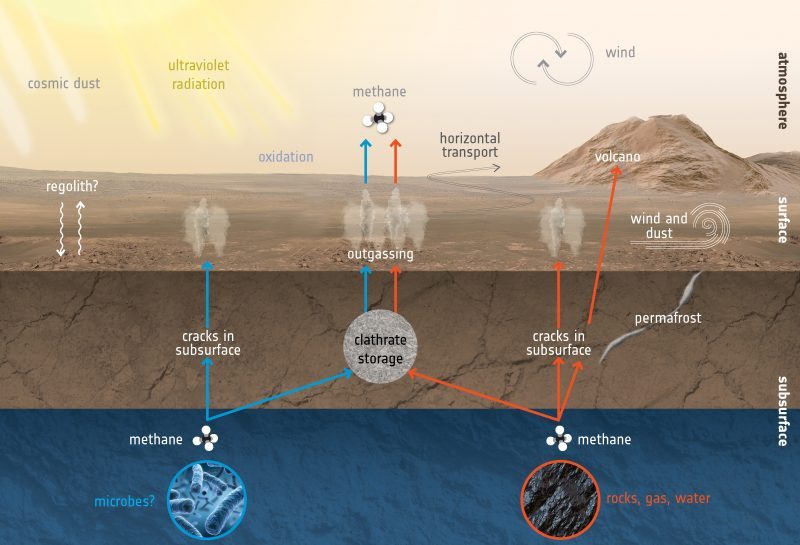

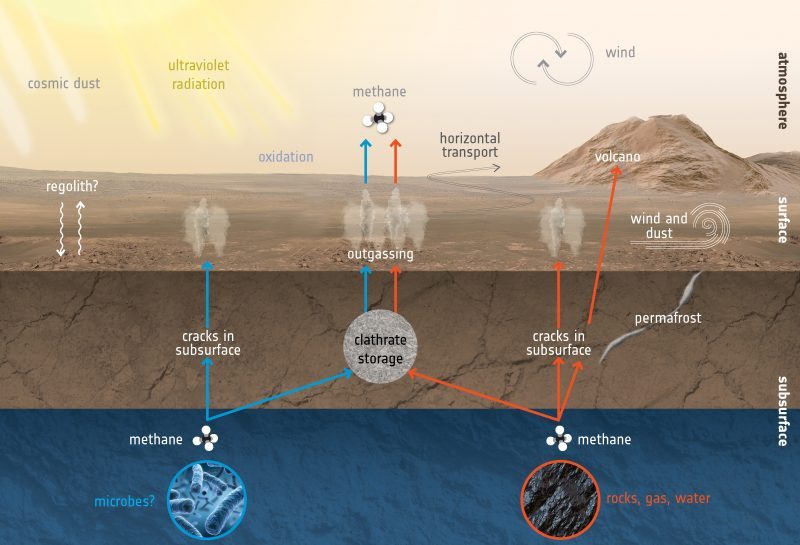

Most scientists now think the methane originates from underground, perhaps as ice clathrates that thaw in the summer and release methane, or maybe a biological source that responds to the warmer temperatures. Even if the methane is bound up in clathrates, the actual origin of it could still be either geological of biological (ancient life). Or it may be produced by warm groundwater interacting with olivine in rocks. If so, that would indicate that there is still some residual geological activity below Mars’ surface, and that itself could provide a habitable environment for microorganisms, even if they didn’t actually produce the methane. Other causes, such as meteorites or comets, probably wouldn’t produce enough of the gas to match observations, either, according to recent studies.

Last April, a new report showed that a spike in methane levels was detected at the same time – for the first time – by both the Curiosity rover and the orbiting Mars Express back in 2013. And last June, Curiosity detected its largest-ever measurement of methane so far. Why are there these peaks in methane emissions, only for the gas to virtually disappear afterwards? There is still a lot we don’t know, as Emmal Safi, a postdoctoral researcher at Newcastle University, indicated:

It’s still an open question. Our paper is just a little part of a much bigger story.

Ultimately, what we’re trying to discover is if there’s the possibility of life existing on planets other than our own, either living now or maybe life in the past that is now preserved as fossils or chemical signatures.

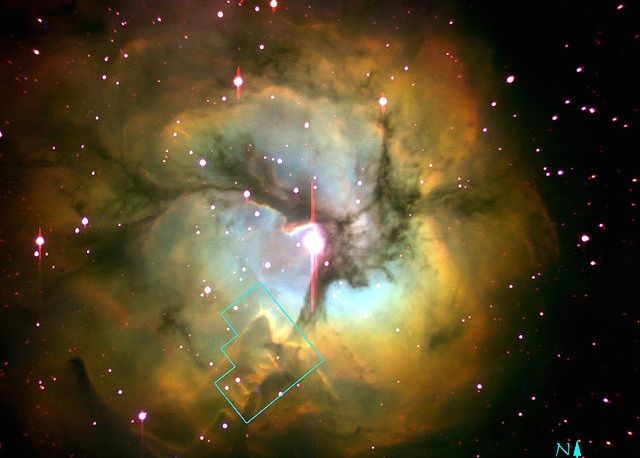

Illustration depicting what processes could create and destroy methane on Mars. The methane most likely originates from below the surface and is released into the atmosphere through subsurface cracks. Image via ESA.

The idea that Mars’ methane might come from life is an exciting one, of course, since most of the methane on Earth is produced by living organisms. But non-biological explanations would need to be eliminated first. The research from Newcastle University shows that at least one of the possible geological explanations for the methane is unlikely, but there is still a lot of work for scientists to do to determine just what is producing it.

Bottom line: This new study would seem to eliminate one possible source of Mars’ methane: wind erosion of rocks on the surface. This bolsters the probability that the methane originates from underground.

Source: Aeolian abrasion of rocks as a mechanism to produce methane in the Martian atmosphere

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2MsFzMI

Mars is a rocky world, and some scientists have theorized that erosion by wind causes Mars rocks to produce methane. But a new study from Newcastle University refutes that. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Phys.org.

What is producing methane on Mars? That is a question that scientists have been trying to answer for quite some time now. There are various possibilities, both geological and biological, but narrowing them down has been a challenge. Could it really be a sign of … life? Now, a new study has shown that at least one of the geological scenarios is very unlikely: wind erosion of rocks.

Researchers at Newcastle University in the U.K. published their peer-reviewed findings in Scientific Reports on June 3, 2019, and a new press release was issued on August 12, 2019. From the article abstract:

Seasonal changes in methane background levels and methane spikes have been detected in situ a metre above the martian surface, and larger methane plumes detected via ground-based remote sensing, however their origin have not yet been adequately explained. Proposed methane sources include the UV irradiation of meteoritic-derived organic matter, hydrothermal reactions with olivine, organic breakdown via meteoroid impact, release from gas hydrates, biological production, or the release of methane from fluid inclusions in basalt during aeolian erosion. Here we quantify for the first time the potential importance of aeolian abrasion as a mechanism for releasing trapped methane from within rocks, by coupling estimates of present day surface wind abrasion with the methane contents of a variety of martian meteorites, analogue terrestrial basalts and analogue terrestrial sedimentary rocks. We demonstrate that the abrasion of basalt under present day Martian rates of aeolian erosion is highly unlikely to produce detectable changes in methane concentrations in the atmosphere. We further show that, although there is a greater potential for methane production from the aeolian abrasion of certain sedimentary rocks, to produce the magnitude of methane concentrations analysed by the Curiosity rover they would have to contain methane in similar concentrations as economic reserved of biogenic/thermogenic deposits on Earth. Therefore we suggest that aeolian abrasion is an unlikely origin of the methane detected in the martian atmosphere, and that other methane sources are required.

A history of key methane measurements on Mars from 1999 to 2018. Image via ESA.

One of the more recent theories was that wind erosion of rocks could produce the methane detected in the lower atmosphere. But the team’s findings showed that it wouldn’t be able to produce methane in the amounts observed, according to Jon Telling, a geochemist at Newcastle University:

The questions are – where is this methane coming from, and is the source biological? That’s a massive question and to get to the answer we need to rule out lots of other factors first.

We realized one potential source of the methane that people hadn’t really looked at in any detail before was wind erosion, releasing gases trapped within rocks. High resolution imagery from orbit over the last decade have shown that winds on Mars can drive much higher local rates of sand movement, and hence potential rates of sand erosion, than previously recognised.

In fact, in a few cases, the rate of erosion is estimated to be comparable to those of cold and arid sand dune fields on Earth.

Using the data available, we estimated rates of erosion on the surface of Mars and how important it could be in releasing methane.

And taking all that into account we found it was very unlikely to be the source.

What’s important about this is that it strengthens the argument that the methane must be coming from a different source. Whether or not that’s biological, we still don’t know.

Artist’s concept of ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter, part of the ExoMars mission, analyzing the Martian atmosphere. Image via ESA/ATG MediaLab.

Observations from both orbiting spacecraft and the Curiosity rover, as well as telescopes on Earth, have shown that methane levels in the Martian atmosphere appear to be seasonal, peaking in the summer and fading again in the winter. Just why that is isn’t known yet, but it indicates a regular process is occurring, whether geological or biological. Oddly, ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) hasn’t detected any methane yet, although that is one of its main objectives. But that may simply be because of the seasonality of the methane, or because TGO focuses its observations on the upper levels of the atmosphere, and most of the other methane detections have been closer to the ground.

Most scientists now think the methane originates from underground, perhaps as ice clathrates that thaw in the summer and release methane, or maybe a biological source that responds to the warmer temperatures. Even if the methane is bound up in clathrates, the actual origin of it could still be either geological of biological (ancient life). Or it may be produced by warm groundwater interacting with olivine in rocks. If so, that would indicate that there is still some residual geological activity below Mars’ surface, and that itself could provide a habitable environment for microorganisms, even if they didn’t actually produce the methane. Other causes, such as meteorites or comets, probably wouldn’t produce enough of the gas to match observations, either, according to recent studies.

Last April, a new report showed that a spike in methane levels was detected at the same time – for the first time – by both the Curiosity rover and the orbiting Mars Express back in 2013. And last June, Curiosity detected its largest-ever measurement of methane so far. Why are there these peaks in methane emissions, only for the gas to virtually disappear afterwards? There is still a lot we don’t know, as Emmal Safi, a postdoctoral researcher at Newcastle University, indicated:

It’s still an open question. Our paper is just a little part of a much bigger story.

Ultimately, what we’re trying to discover is if there’s the possibility of life existing on planets other than our own, either living now or maybe life in the past that is now preserved as fossils or chemical signatures.

Illustration depicting what processes could create and destroy methane on Mars. The methane most likely originates from below the surface and is released into the atmosphere through subsurface cracks. Image via ESA.

The idea that Mars’ methane might come from life is an exciting one, of course, since most of the methane on Earth is produced by living organisms. But non-biological explanations would need to be eliminated first. The research from Newcastle University shows that at least one of the possible geological explanations for the methane is unlikely, but there is still a lot of work for scientists to do to determine just what is producing it.

Bottom line: This new study would seem to eliminate one possible source of Mars’ methane: wind erosion of rocks on the surface. This bolsters the probability that the methane originates from underground.

Source: Aeolian abrasion of rocks as a mechanism to produce methane in the Martian atmosphere

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2MsFzMI