Although several dozen minor galaxies lie closer to our Milky Way, the Andromeda galaxy is the closest large spiral galaxy to ours. Excluding the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, which can’t be seen from northerly latitudes, the Andromeda galaxy – also known as M31 – is the brightest galaxy you can see. At 2.5 million light-years, it’s also the most distant thing visible to your unaided eye.

To the eye, this galaxy appears as a smudge of light larger than a full moon.

Josh Blash captured this image of the Andromeda galaxy. It’s big, bigger than a full moon. If you know approximately where to look for this hazy smudge in your night sky – and your sky is very dark – you might pick out the galaxy just by looking for it.

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Meteors in the same field of view as the Andromeda galaxy. Omid Ghadrdan in Iran caught the scene on August 11, 2019, and wrote, “What can I say? Wonders of the universe. Just compare the golf-ball-sized meteors with the galaxy bigger than ours.” Thank you, Omid!

When to look for the Andromeda Galaxy. From mid-northern latitudes, you can see M31 – also called the Andromeda galaxy – for at least part of every night, all year long. But most people see the galaxy first around northern autumn, when it’s high enough in the sky to be seen from nightfall until daybreak.

In late August and early September, begin looking for the galaxy in mid-evening, about midway between your local nightfall and midnight.

In late September and early October, the Andromeda galaxy shines in your eastern sky at nightfall, swings high overhead in the middle of the night, and stands rather high in the west at the onset of morning dawn.

Winter evenings are also good for viewing the Andromeda galaxy.

If you are far from city lights, and it’s a moonless night – and you’re looking on a late summer, autumn or winter evening – it’s possible you’ll simply notice the galaxy in your night sky. It’s looks like a hazy patch in the sky, as wide across as a full moon.

But if you look, and don’t see the galaxy – yet you know you’re looking at a time when it’s above the horizon – you can star-hop to find the galaxy in one of two ways. The easiest way is to use the constellation Cassiopeia. You can also use the Great Square of Pegasus.

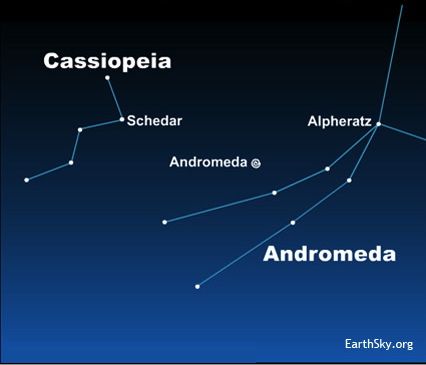

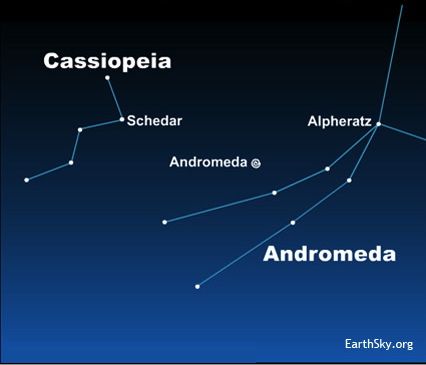

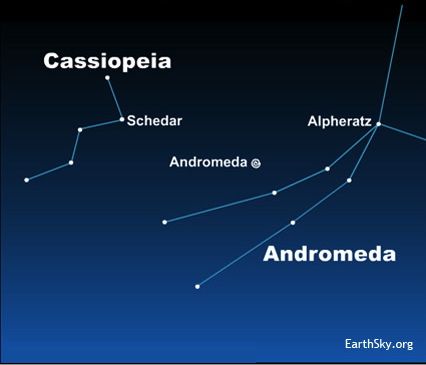

Most people use the M- or W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia to find the Andromeda galaxy. See how the star Schedar points to the galaxy?

Find the Andromeda galaxy using the constellation Cassiopeia. The constellation Cassiopeia the Queen is one of the easiest constellations to recognize. It’s shaped like the letter M or W. Look generally northward on the sky’s dome to find this constellation. If you can recognize the North Star, Polaris – and if you know how to find the Big Dipper – be aware that the Big Dipper and Cassiopeia move around Polaris like the hands of a clock, always opposite each other.

To find the Andromeda galaxy via Cassiopeia, look for the star Schedar. In the illustration above, see how the star Schedar points to the galaxy?

Most people use Cassiopeia to find the Andromeda galaxy, because Cassiopeia itself is so easy to spot.

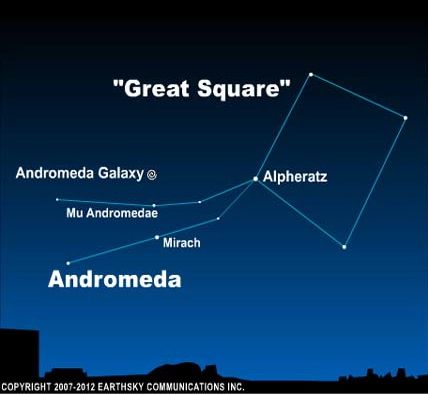

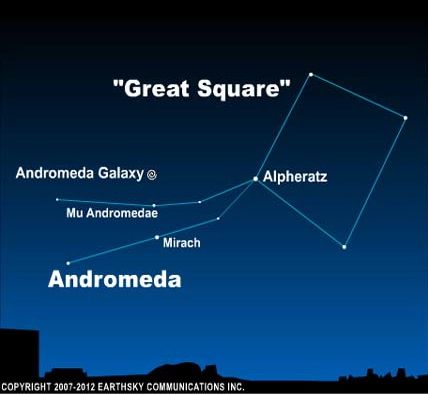

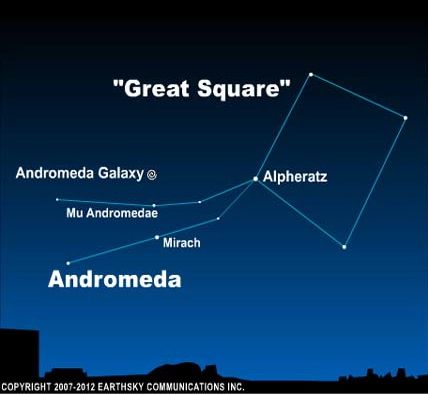

Use the Great Square of Pegasus to find the Andromeda Galaxy. A line between Mirach and Mu Andromedae points to the galaxy.

Find the Andromeda galaxy using the Great Square of Pegasus. Here’s another way to find the galaxy. It’s a longer route, but, in many ways, more beautiful.

You’ll be hopping to the Andromeda galaxy from the Great Square of Pegasus. In autumn, the Great Square of Pegasus looks like a great big baseball diamond in the eastern sky. Envision the bottom star of the Square’s four stars as home plate, then draw an imaginary line from the “first base” star though the “third base” star to locate two streamers of stars flying away from the Great Square. These stars belong to the constellation Andromeda the Princess.

On each streamer, go two stars north (left) of the third base star, locating the stars Mirach and Mu Andromedae. Draw a line from Mirach through Mu Andromedae, going twice the Mirach/Mu Andromedae distance. You’ve just landed on the Andromeda galaxy, which looks like a smudge of light to the unaided eye.

If you can’t see the Andromeda galaxy with the eye alone, by all means use binoculars.

The Great Andromeda Nebula, photographed in the year 1900. At this point, astronomers could not discern individual stars in the galaxy. Many thought it was a cloud of gas within our Milky Way – a place where new stars were forming.Image via Wikimedia Commons.

History of our knowledge of the Andromeda galaxy. At one time, the Andromeda galaxy was called the Great Andromeda Nebula. Astronomers thought this patch of light was composed of glowing gases, or was perhaps a solar system in the process of formation.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that astronomers were able to resolve the Andromeda spiral nebula into individual stars. This discovery lead to a controversy about whether the Andromeda spiral nebula and other spiral nebulae lie within or outside the Milky Way.

In the 1920s Edwin Hubble finally put the matter to rest, when he used Cepheid variable stars within the Andromeda galaxy to determine that it is indeed an island universe residing beyond the bounds of our Milky Way galaxy.

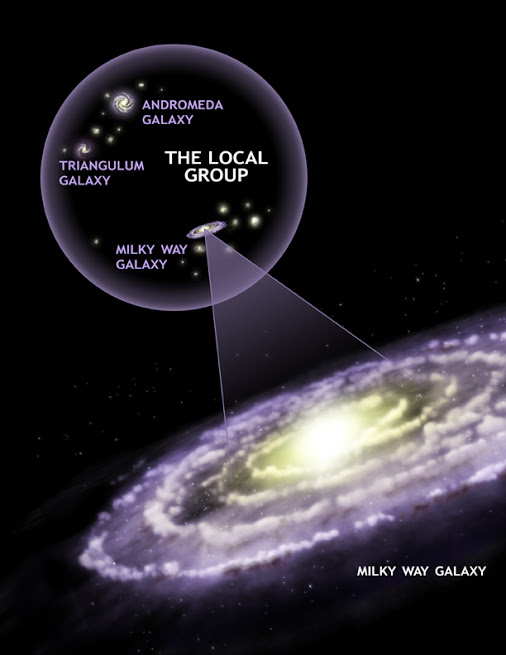

Andromeda and Milky Way in context. The Andromeda galaxy and our Milky Way galaxy reign as the two most massive and dominant galaxies within the Local Group of Galaxies. The Andromeda Galaxy is the largest galaxy of the Local Group, which, in addition to the Milky Way, also contains the Triangulum Galaxy and about 30 other smaller galaxies.

Both the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxies lay claim to about a dozen satellite galaxies. Both are some 100,000 light-years across, containing enough mass to make billions of stars.

Astronomers have discovered that our Local Group is on the outskirts of a giant cluster of several thousand galaxies, which astronomers call the Virgo Cluster.

We also know of an irregular supercluster of galaxies, which contains the Virgo Cluster, which in turn contains our Local Group, which in turn contains our Milky Way galaxy and the nearby Andromeda galaxy. At least 100 galaxy groups and clusters are located within this Virgo Supercluster. Its diameter is thought to be about 110 million light-years.

The Virgo Supercluster is thought to be one of millions of superclusters in the observable universe.

The Andromeda galaxy (M31) is at RA: 0h 42.7m; Dec: 41o 16′ north

Bottom line: At 2.5 million light-years, the Great Andromeda galaxy (Messier 31) rates as the most distant object you can see with the unaided eye.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2GZ8J1Y

Although several dozen minor galaxies lie closer to our Milky Way, the Andromeda galaxy is the closest large spiral galaxy to ours. Excluding the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, which can’t be seen from northerly latitudes, the Andromeda galaxy – also known as M31 – is the brightest galaxy you can see. At 2.5 million light-years, it’s also the most distant thing visible to your unaided eye.

To the eye, this galaxy appears as a smudge of light larger than a full moon.

Josh Blash captured this image of the Andromeda galaxy. It’s big, bigger than a full moon. If you know approximately where to look for this hazy smudge in your night sky – and your sky is very dark – you might pick out the galaxy just by looking for it.

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Meteors in the same field of view as the Andromeda galaxy. Omid Ghadrdan in Iran caught the scene on August 11, 2019, and wrote, “What can I say? Wonders of the universe. Just compare the golf-ball-sized meteors with the galaxy bigger than ours.” Thank you, Omid!

When to look for the Andromeda Galaxy. From mid-northern latitudes, you can see M31 – also called the Andromeda galaxy – for at least part of every night, all year long. But most people see the galaxy first around northern autumn, when it’s high enough in the sky to be seen from nightfall until daybreak.

In late August and early September, begin looking for the galaxy in mid-evening, about midway between your local nightfall and midnight.

In late September and early October, the Andromeda galaxy shines in your eastern sky at nightfall, swings high overhead in the middle of the night, and stands rather high in the west at the onset of morning dawn.

Winter evenings are also good for viewing the Andromeda galaxy.

If you are far from city lights, and it’s a moonless night – and you’re looking on a late summer, autumn or winter evening – it’s possible you’ll simply notice the galaxy in your night sky. It’s looks like a hazy patch in the sky, as wide across as a full moon.

But if you look, and don’t see the galaxy – yet you know you’re looking at a time when it’s above the horizon – you can star-hop to find the galaxy in one of two ways. The easiest way is to use the constellation Cassiopeia. You can also use the Great Square of Pegasus.

Most people use the M- or W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia to find the Andromeda galaxy. See how the star Schedar points to the galaxy?

Find the Andromeda galaxy using the constellation Cassiopeia. The constellation Cassiopeia the Queen is one of the easiest constellations to recognize. It’s shaped like the letter M or W. Look generally northward on the sky’s dome to find this constellation. If you can recognize the North Star, Polaris – and if you know how to find the Big Dipper – be aware that the Big Dipper and Cassiopeia move around Polaris like the hands of a clock, always opposite each other.

To find the Andromeda galaxy via Cassiopeia, look for the star Schedar. In the illustration above, see how the star Schedar points to the galaxy?

Most people use Cassiopeia to find the Andromeda galaxy, because Cassiopeia itself is so easy to spot.

Use the Great Square of Pegasus to find the Andromeda Galaxy. A line between Mirach and Mu Andromedae points to the galaxy.

Find the Andromeda galaxy using the Great Square of Pegasus. Here’s another way to find the galaxy. It’s a longer route, but, in many ways, more beautiful.

You’ll be hopping to the Andromeda galaxy from the Great Square of Pegasus. In autumn, the Great Square of Pegasus looks like a great big baseball diamond in the eastern sky. Envision the bottom star of the Square’s four stars as home plate, then draw an imaginary line from the “first base” star though the “third base” star to locate two streamers of stars flying away from the Great Square. These stars belong to the constellation Andromeda the Princess.

On each streamer, go two stars north (left) of the third base star, locating the stars Mirach and Mu Andromedae. Draw a line from Mirach through Mu Andromedae, going twice the Mirach/Mu Andromedae distance. You’ve just landed on the Andromeda galaxy, which looks like a smudge of light to the unaided eye.

If you can’t see the Andromeda galaxy with the eye alone, by all means use binoculars.

The Great Andromeda Nebula, photographed in the year 1900. At this point, astronomers could not discern individual stars in the galaxy. Many thought it was a cloud of gas within our Milky Way – a place where new stars were forming.Image via Wikimedia Commons.

History of our knowledge of the Andromeda galaxy. At one time, the Andromeda galaxy was called the Great Andromeda Nebula. Astronomers thought this patch of light was composed of glowing gases, or was perhaps a solar system in the process of formation.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that astronomers were able to resolve the Andromeda spiral nebula into individual stars. This discovery lead to a controversy about whether the Andromeda spiral nebula and other spiral nebulae lie within or outside the Milky Way.

In the 1920s Edwin Hubble finally put the matter to rest, when he used Cepheid variable stars within the Andromeda galaxy to determine that it is indeed an island universe residing beyond the bounds of our Milky Way galaxy.

Andromeda and Milky Way in context. The Andromeda galaxy and our Milky Way galaxy reign as the two most massive and dominant galaxies within the Local Group of Galaxies. The Andromeda Galaxy is the largest galaxy of the Local Group, which, in addition to the Milky Way, also contains the Triangulum Galaxy and about 30 other smaller galaxies.

Both the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxies lay claim to about a dozen satellite galaxies. Both are some 100,000 light-years across, containing enough mass to make billions of stars.

Astronomers have discovered that our Local Group is on the outskirts of a giant cluster of several thousand galaxies, which astronomers call the Virgo Cluster.

We also know of an irregular supercluster of galaxies, which contains the Virgo Cluster, which in turn contains our Local Group, which in turn contains our Milky Way galaxy and the nearby Andromeda galaxy. At least 100 galaxy groups and clusters are located within this Virgo Supercluster. Its diameter is thought to be about 110 million light-years.

The Virgo Supercluster is thought to be one of millions of superclusters in the observable universe.

The Andromeda galaxy (M31) is at RA: 0h 42.7m; Dec: 41o 16′ north

Bottom line: At 2.5 million light-years, the Great Andromeda galaxy (Messier 31) rates as the most distant object you can see with the unaided eye.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2GZ8J1Y

.

.

.

.